Photo: Adam Jones.

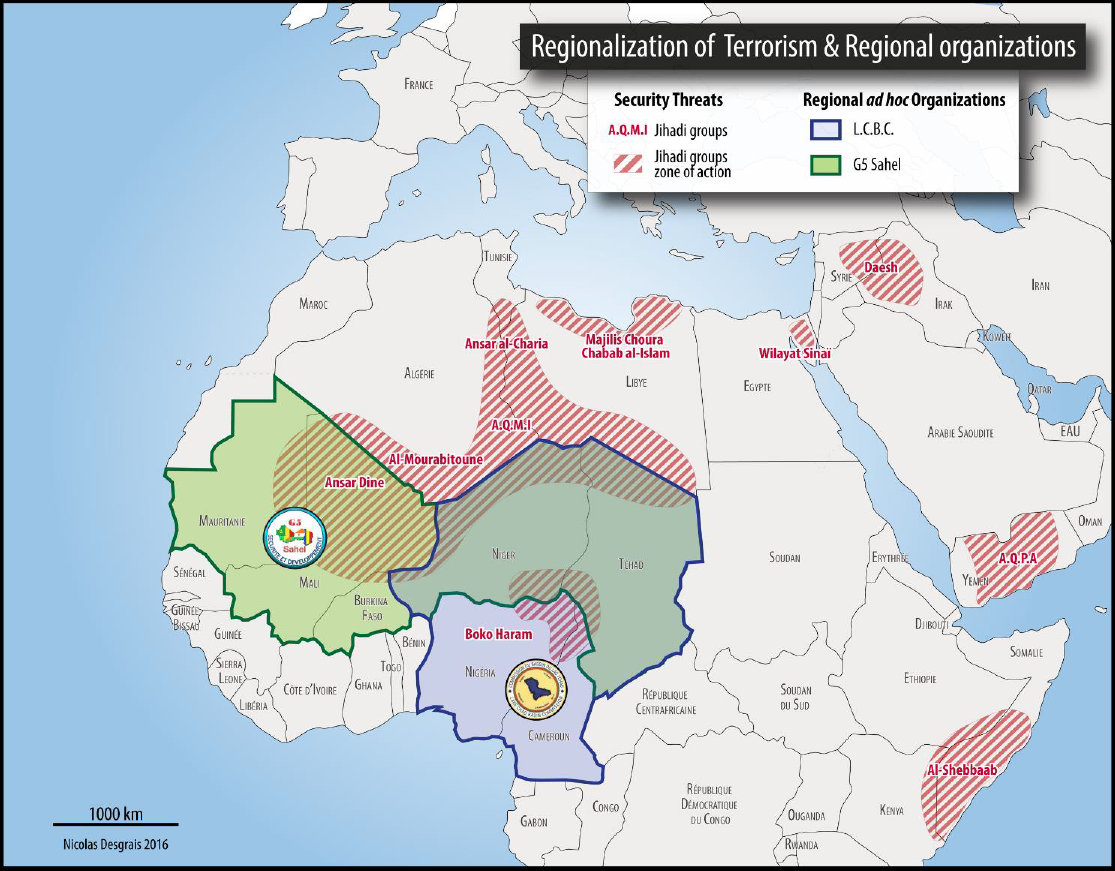

The G5 Sahel was established in 2014 as an inter-governmental partnership among Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger to foster economic cooperation and security in the Sahelian region. The growing virulence of militant Islamist groups, taking advantage of sparsely populated border areas, has posed a serious challenge to the G5 vision, however.

In response, the G5 Sahel ramped up its security efforts by launching a joint security force (Force Conjointe du G5 Sahel) to combat terrorism, drug trafficking, and human trafficking in 2017. The Force was subsequently endorsed by the African Union’s Peace and Security Council and the UN Security Council and has the support of a variety of international partners. The G5 Sahel Joint Force is now expected to be at the forefront of transnational security efforts in the Sahel for the near future. So what is this Force, what are its objectives, and how will it work with or complement existing national and regional security initiatives?

Why Was the G5 Sahel Joint Force Formed?

G5 Sahel members saw the need to respond to the challenging regional security environment as a strategic priority. Militant Islamist groups threaten the security of populations across the region and exacerbate other security challenges, including forced displacement, organized crime, and human trafficking. These challenges persist despite the routing of militant Islamist groups from northern Mali in 2013 by a coalition of French and African forces that had deployed in response to the seizure of large tracts of territory in northern Mali by militant Islamist groups. The subsequent deployment of the UN peace operation in Mali, MINUSMA, and the French operation, Barkhane, and the continuing efforts to build capacity of national security forces across the region have blunted the threat.

Still, challenges remain. Eight different militant Islamist groups have been linked to over 1,100 fatalities since 2014, including nearly 400 in 2017. The most active of these groups is Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and its affiliates (operating collectively under the banner Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin), as well as the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara.

Their activities have included attacks on civilians in remote villages, ambushes on military bases and personnel, and high-profile bombings of popular hotels and restaurants of capital cities in the region. In two separate incidents in January 2018, 39 civilians were killed when their vehicles hit landmines in central Mali. In August 2017, three UN bases in central and northern Mali were ambushed, killing eight peacekeepers. Having incurred more than 118 fatalities since 2014, MINUSMA is considered the world’s most dangerous UN mission. In October 2017, four U.S. and five Nigerien servicemen were killed in an ambush in Niger near the Mali border. Militants struck nearby later that month, killing 13 Nigerien gendarmes. In January 2016, 30 people were killed in an attack on a hotel and café in Ouagadougou.

The scattered nature of these attacks, porous borders, and the limited security presence in remote and sparsely populated areas allow militant Islamist groups to extend their activities across the region. As they gain control of trade routes, they also engage in illicit activities such as drug trafficking and weapons smuggling. This has hindered travel and legal commerce, further harming economic conditions for communities throughout the Sahel.

The region is also grappling with unprecedented levels of forced displacement. Chad is the fifth largest refugee host country in Africa, hosting around 391,000 refugees, mainly from Nigeria, Sudan, and the Central African Republic. Malians account for 22 percent of the refugees in Niger, while those displaced from Nigeria, mainly due to Boko Haram attacks, account for the remaining 78 percent. Boko Haram attacks have also displaced 248,000 people to Niger’s Diffa region, including 105,000 Nigerians and 15,000 from Niger itself. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) observed that almost 63,000 people transited out of Niger through Séguédine and Arlit in 2017. In Mali, IOM observed an average of 208 people leaving daily. In Burkina Faso, the figure was 230.

In short, the launching of the G5 Sahel Joint Force is intended to reverse the instability in the region caused by militant groups that is having a chilling effect on travel, trade, and economic activity, and is triggering large-scale population displacements.

How Will the Force Operate?

The G5 Sahel concept of operations has four pillars:

- Combat terrorism and drug trafficking

- Contribute to the restoration of state authority and the return of displaced persons and refugees

- Facilitate humanitarian operations and the delivery of aid to affected populations

- Contribute to the implementation of development strategies in the G5 Sahel region

The Force consists of 5,000 predominantly military troops from its five member states, including seven 550-soldier battalions, plus 100 police and gendarmes. These troops are spread over three sectors: Western (Mali and Mauritania), Central (Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger), and Eastern (Chad and Niger). Its main areas of operation are the border areas between Mali and Mauritania; Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger; and Chad and Niger. At the end of 2017, a Force headquarters was set up in Sévaré, Mali. Secondary command posts will be set up in each sector. In addition, a 50-kilometer zone along each border has been set up to allow national contingents to conduct joint operations or pursue targets beyond their own borders.

Source: Nicolas Desgrais, “La Force Conjointe du G5 Sahel (FC-G5S) Ou l’émergence d’une architecture de défense collective propre au Sahel,” Conseil Supérieur de la Formation et de la Recherche Stratégique, Paris, December 2017.

Challenges for Deployment: Funding and Coordination

The UN has encouraged international contributions to the G5 Sahel Joint Force’s $523 million initial budget but says that responsibility for funding ultimately lies with the G5 member countries. Each has pledged $10 million, while the EU, at a conference held in Brussels in late February, increased its pledge from $61 million to $143 million (€116 million). France and Germany contributed a combined $21.7 million and launched a mobilization effort to meet the rest of the G5’s financial needs through bilateral contributions. This effort has raised contributions from Spain, the Netherlands, Norway, Japan, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Czech Republic, and Slovenia, with further commitments expected. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have pledged $100 million and $30 million respectively, with an additional $60 million coming from the United States. France, moreover, has pledged a further $1.5 billion (€1.2 billion) in development assistance over the next five years and the EU will invest $9.8 billion (€8 billion) in development assistance to the Sahel over the next five years.

In addition to its financial contributions, France provides significant combat support through Operation Barkhane, a French security collaboration initiative with the Sahel nations that has been ongoing since 2014. Around 4,000 French troops are involved in the operation, which is based in Chad, Burkina Faso, and Mali and operates across the entire southern Sahara area. (Barkhane, in turn, evolved out of Operation Serval in 2013—the French- and Chadian-led intervention in northern Mali to recover territory lost to militant Islamist groups that threatened to sweep down to Bamako.)

Aside from the operational challenges of combating militant groups, the G5 Sahel Joint Force must tailor its institutional focus in consideration of other ongoing regional security initiatives. MINUSMA is mandated to support political processes in Mali and carry out security-related tasks to stabilize the country and implement the government’s transitional roadmap. The 10,000-strong Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), consisting of troops from Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria mandated to end the Boko Haram terrorist insurgency, is another focus of operations and cooperation. Given that some of the same security partners are involved in each of these missions, efforts in clarifying their respective roles and reconciling mandates is central to the overall counterterrorism and stabilization effort.

For example, there is some overlap in troop-contributing countries’ membership in various security bodies. Chad and Niger contribute troops to MINUSMA and the MNJTF, and over 1,000 Mauritanian troops also serve in MINUSCA. Security partners will therefore need to ensure they are not overextended across multiple missions (see table).[ultimatetables 1 /]

More generally, the G5 Sahel Joint Force will also need to be reconciled with the AU’s African Peace and Security Architecture that is structured to facilitate collective security cooperation through the Regional Economic Communities (REC). One of the operational challenges to this, however, has been that the members of the G5 (or the MNJTF) do not all belong to the same REC.

To be effective, G5 coordination must also extend beyond military agencies. As expressed in the G5 Sahel Joint Force concept of operations, economic development in marginalized areas is crucial, as it can help inhibit recruitment of violent extremist groups and stabilize these areas. Ensuring that coalition forces uphold standards of military professionalism and human rights will also be imperative so as not to alienate local communities. Effectively implementing these development initiatives in coordination with military action will require a high level of integration across various lines of effort.

It remains too soon to say how effective the G5’s elevated security efforts will be. Its creation, however, reflects the recognition of the need for a regional security structure in the Sahel that can combat the cross-border security threat posed by violent extremist groups while creating viable economic and governance alternatives in these long-neglected border regions.

Africa Center Experts

- Benjamin Nickels, Associate Professor of Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency

- Jean-Baptiste Matton, Senior French Representative

- Alix Boucher, Assistant Research Fellow

Additional Resources

- International Crisis Group, “Finding the Right Role for the G5 Sahel Joint Force,” Report No. 258, December 12, 2017.

- Nicolas Desgrais, “La Force Conjointe du G5 Sahel (FC-G5S) Ou l’émergence d’une architecture de défense collective propre au Sahel,” Conseil Supérieur de la Formation et de la Recherche Stratégique, Paris, December 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The Evolution of Militant Islamist Group Activity in Africa 2010–2016,” Infographic, January 10, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Extremism: Root Causes, Drivers, and Responses,” Spotlight, November 20, 2015.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Trajectories of Terrorist and Armed Groups in Africa,” Spotlight, November 12, 2015.

- Laurence Aïda Ammour, “Regional Security Cooperation in the Maghreb and Sahel: Algeria’s Pivotal Ambivalence,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 18, February 28, 2012.

- Terje Østebø, “Islamic Militancy in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 23, November 30, 2012.

- Cédric Jourde, “Sifting Through the Layers of Insecurity in the Sahel: The Case of Mauritania,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 15, September 30, 2011.

- Modibo Goïta, “West Africa’s Growing Terrorist Threat: Confronting AQIM’s Sahelian Strategy,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 11, February 28, 2011.

More on: Counter Narcotics Countering Violent Extremism Peacekeeping Sahel