Criminal bandit gang in Birnin Magaji, Zamfara State. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Murtala Rufa’i)

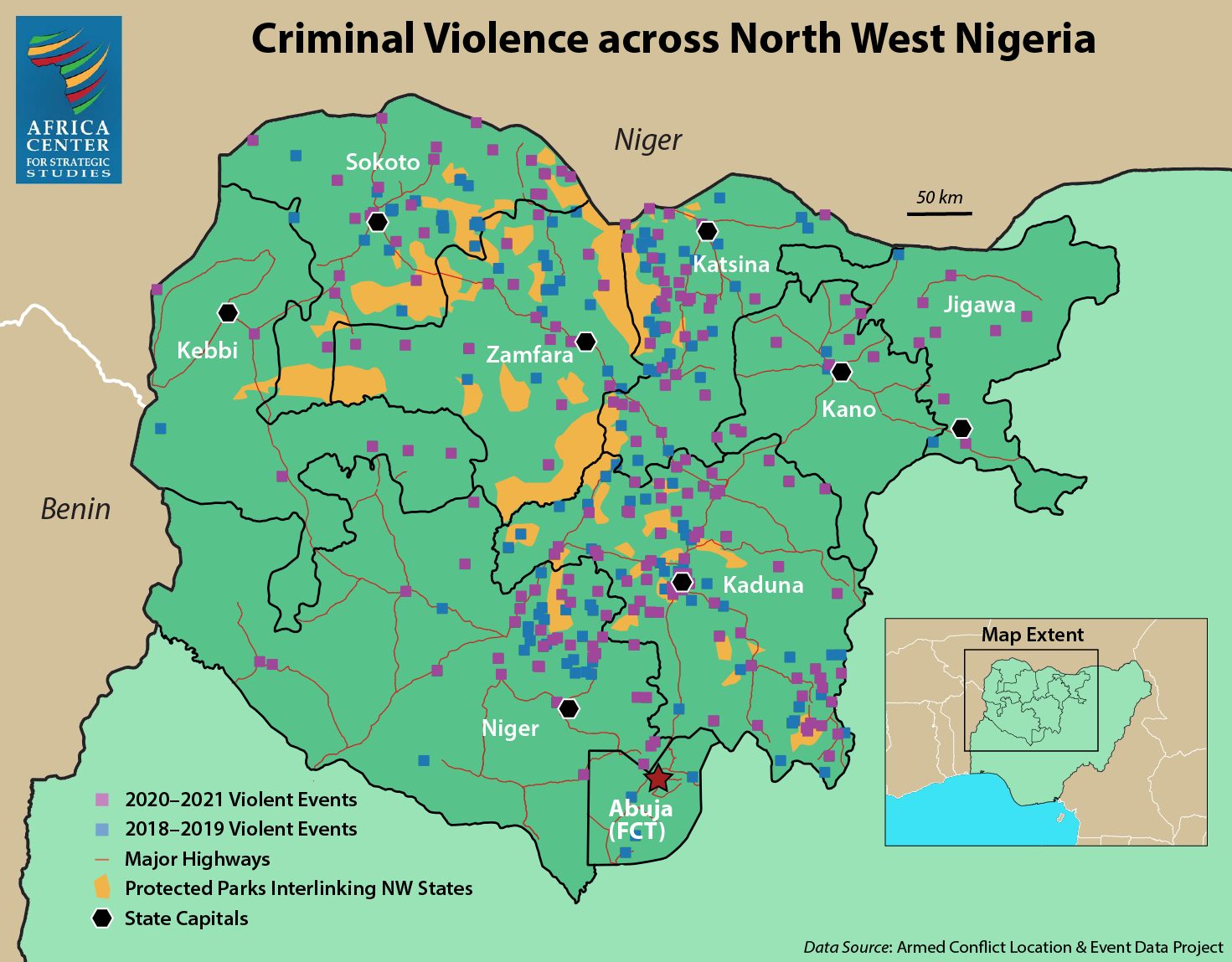

Known in the national media as “bandits,” small gangs of criminals have been increasingly menacing the North West region of Nigeria, scoring cattle, plunder, and ransoms from rural farms and villages. These gangs do not hesitate to use violence, including murder, to intimidate villagers into submission. Since 2020, these criminal gangs have reportedly been involved in over 350 violent events linked to over 1,500 fatalities. This represents an approximately 45-percent increase in attacks and a 65-percent increase in fatalities compared to the 2018–19 period. Many smaller attacks and abductions go unreported.

Emboldened and increasingly organized as sophisticated criminal enterprises, these gangs have made global headlines with a series of mass kidnapping raids on boarding schools in Kaduna, Katsina, Niger, and Zamfara States. Victims are typically then held for hefty ransoms, often bankrupting the affected family. Increasingly vulnerable to these raids, hundreds of schools have closed and over one million children in the region are not attending classes.

These incidents and other attacks have spurred Nigerian authorities to impose a blackout of mobile telecommunications in the region and restrict movement and large gatherings. Most recently, a federal court ruled at the behest of the Director of Public Prosecutions that the North West’s criminal gangs constitute “terrorists,” paving the way for a loosening of the rules of military engagement. An indiscriminate security response, however, could well escalate the instability.

The Africa Center for Strategic Studies spoke to two Nigerian experts about the deteriorating security conditions in the North West. Kunle Adebajo is a journalist who has reported extensively on the banditry crisis, and Dr. Murtala Rufa’i is a lecturer in the Department of History, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto.

* * *

Why has the insecurity and humanitarian crisis affecting States in the North West worsened recently?

ADEBAJO: The situation in the North West is indeed worsening. There has been an increase in the number of violent incidents, fatalities, and kidnap victims as documented by the [Council on Foreign Relations’] Nigeria Security Tracker (NST). There has been a doubling of kidnapping in 2021 in the North West compared to 2020. This continues a worsening trend for the past several years, resulting in fatalities that are nearing 1,000 annually. This is likely a significant undercount. There are now over 450,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) according to the International Organization for Migration—other sources suggest even higher totals.

Previously, attacks had been mostly concentrated in rural areas, but now the bandits are venturing further away from their hideouts in the remotest communities. This is because many of those areas have been raided repeatedly and are increasingly impoverished. So bandit groups are turning their attention to urban communities to get more money, to rustle more cattle, and to get larger ransoms. Now you find bandit gangs more frequently attacking local government headquarters and bigger communities that are closer to federal highways—especially since they have acquired the manpower and arms to confront bigger targets. This year, bandits have attacked military bases and police stations in Zamfara and Sokoto, which gave them access to greater firepower.

Another major factor is the absence of adequate policing and military architecture in the affected areas. Communities that have a mobile police patrol team (MOPOL) have become like the garrison towns of the North East and are significantly safer than others. So, people who do not have a similar police presence migrate to these places, either permanently or just at night when attacks are most frequent. The presence of vigilante or community-based armed groups has also been found to deter bandits. This is a double-edged sword though, because renegade vigilantes may mount reprisal attacks on neighboring herding communities, contributing to further escalation. In the process, there are many excesses and extrajudicial killings.

Nigeria’s MOPOL

Police in Kaduna State. (Photo: Allan Leonard)

The Mobile Police, also known as the MOPOL, is a paramilitary unit of the Nigeria Police originally established in 1961 as an anti-riot squad. Its functions have, however, expanded into other areas including containing large-scale armed violence. The officers are deployed across the country to protect national assets and important individuals, enforce law and order in unstable areas, and fight violent non-state actors. Believed to be more effective than the average police officer, the personnel are actively engaged as part of the counterinsurgency operations in the North East and also have a prominent presence in the North West where they protect communities against bandits.

RUFA’I: For years security in the North West has been deteriorating because the federal and state governments have not appreciated the gravity of the banditry problem and have historically sought to downplay it (at times refusing access to aid groups and disallowing the establishment of IDP camps). The government has not invested in understanding the regional dynamics and how bandit groups operate within it, and, therefore, have never developed consistent or coordinated policies to address the rising kidnappings and raids conducted by these criminal gangs.

In the past year, COVID measures—including the international border closure with Niger, market restrictions, and partial lockdowns—created a lot of hardships for people in the North West region. Poverty and unemployment increased, which we have documented in surveys of rural communities. At first cross-border trade came to a standstill, but then informal trading activity picked back up. However, corruption and bribery increased since these activities were officially banned. Bandit gangs took advantage of the situation by providing food supplies to some hard-hit communities and then recruiting young men and informants from them. This is a pattern they have followed in the past—taking advantage of impoverished people when government has been corrupt or absent.

There are several villages that serve as host communities for some gangs. The gangs hide out in the forests nearby and allow the villages to continue normal life so long as these villages provide levies and recruits. In return, the bandits protect these villages from other gangs and occasionally provide them food and other items in times of need.

Who are the armed groups driving the crisis? How many groups are there and what size are they typically? Are these groups large criminal enterprises, each led by an identifiable leader, or are there many smaller roving bands without allegiances and central leadership?

Motorbike in North West Nigeria. (Photo: Jeremy Weate)

ADEBAJO: It is difficult to get exact numbers. A fact-finding committee set up by the government of Zamfara estimated that there were at least 105 bandit camps in and around the State from which the bandits launch attacks. Most of the groups originated in Zamfara and operate out of several forested areas that connect and provide corridors between multiple States, which allows them to move freely. Zamfara borders several North West States: Sokoto, Kebbi, Niger, Kaduna, and Katsina. One researcher has been able to document 62 bandit groups, mostly in Zamfara, with their manpower strength ranging between as few as 28 to as high as 2,500 men. Some of the major bandit leaders are Bello Turji Gudde, Halilu Sububu, Shehu Rekep, and Abubakar Abdullahi (alias Dogo Gide, who is reported to have been killed). The groups are independent of each other but have varying levels of influence over other gangs depending on their size and strength. This is why it is difficult for any dialogue with one gang leader to have a broad effect on the general security situation.

RUFA’I: Historically there have been hundreds of splintered small gangs based between Zamfara and Kaduna States. Different leaders controlled different zones to mitigate squabbles between gangs, but the groups under these warlords had relative autonomy. So, Niger and Kaduna States are under Abubakar Abdallahi. Katsina was under the late Auwalun Daudawa and Dangote Bazamfare. Eastern Sokoto State is under the jurisdiction of Turji. And there are many rival leaders in Zamfara State.

Criminal Gang Activity in Zamfara

A remote town in Zamfara State. (Photo: Osinowo Oluwaseun Omotayo)

Historically, North West Nigeria’s bandit problem originated in Zamfara largely as a result of corrupt land titling processes in the early 2000s that benefited Hausa elites at the expense of herders. The forested areas of Zamfara State are one reason that full-time criminal gangs eventually took root there. The gangs also operate artisanal gold mines in Zamfara and exploit its international border with Niger to profit from arms and narcotics smuggling.

In the past year, many of these once rival gangs have started to join forces against the common enemy of community protection groups and the government as bandit containment measures (communication blackouts, gasoline restrictions, and motorbike bans) have gone into effect. This unity has allowed the gangs to share information on security forces’ movements and to combine manpower to attack larger villages and better-guarded towns. This is a troubling development, but it is not clear whether it will continue since the gangs have historically been fiercely independent and often engaged in skirmishes over their territories.

What do these groups want?

ADEBAJO: Mostly money and relevance. The groups make income from various means: stealing from locals (money, valuables, livestock), levying communities (to use their farms or to provide immunity from attacks for instance), or through ransom payments from individuals and governments. They also, at times, commandeer fertile farmlands, which the gang members then farm themselves.

The bandits have complained in some interviews of being marginalized by the government and of not having access to basic amenities such as education and healthcare. They have protested being discriminated against as Fulani people. But the bandits’ criminal and terror operations are mostly mercantile in nature rather than political or ethnic. Some young men have described how they joined bandit gangs after they themselves were victims of bandit raids and lost everything, leaving them with few other options. We have yet to see any collective grand agenda as is the case with Boko Haram in the North East. Opportunism is their current modus operandi.

RUFA’I: The violence in the North West initially grew out of land disputes driven by environmental degradation, population growth, and especially government corruption around land rights that benefited politically connected elites at the expense of pastoralists who found access to their historical grazing lands and cattle routes blocked. But when gangs recruited from disgruntled pastoralists started attacking farming communities and realized that they had the power, momentum, and ability to raid these communities at will, then the conflict took on a new dimension of being motivated for economic reasons. Some became full-time raiders. Now the violence is fundamentally and purely a criminal activity that is driven by economic gain.

“The violence is fundamentally and purely a criminal activity that is driven by economic gain.”

However, the new government measures are reviving ethnic grievances amongst Fulani in the region who feel like they are being unfairly singled out and targeted by the government containment policies. This sentiment is helping gangs recruit young men whose livelihoods have been affected by these policies. It also helps gangs to opportunistically team up and form alliances under the banner of defending Fulani people. This is so even though the gangs are still attacking Fulani herders and many of the gang members do not even speak Fulani.

In what ways is the current security response working and in what ways is it not? What has worked in the past?

ADEBAJO: The current security response is undoubtedly no match for the scale of the menace. There are not enough police officers on the ground, and those available are not equipped enough for the task. The country’s armed forces are also stretched too thin. There are about 334,000 police officers in the country, but it is estimated that nearly half of those are deployed as armed escorts to politicians or people who can afford the service. This leaves a fraction of the force to protect the rest of the population. The Governor of Katsina recently complained that police officers in his State did not number 3,000.

Previous efforts of negotiating peace treaties and amnesty programs for the bandits in places like Zamfara have so far proved unsuccessful. Though early gains were reported, these arrangements soon fell apart, with the governors expressing frustration with the resurgence in attacks and worsening security situation. These deals did not succeed, oftentimes, because of the fragile leadership of the bandit gangs and the fact that there are so many groups independent of each other.

The security response also needs to be supported by much more surveillance and community policing. This would require building public trust with the security agencies, improving and scaling data collection and profiling exercises, and having enough capable hands in the law enforcement and military agencies to follow-up on intelligence gathered. There are examples of exceptional military commanders who have been very engaged with community-based armed groups and have accompanied their men on raids of bandit camps in the forests. When local communities have seen this kind of dedication, they have been eager to work with them and to provide intelligence. But then these people get reassigned and their replacements, a lot of times, do not match up.

Kaduna city walls. (Photo: Allan Leonard)

RUFA’I: The recent government containment measures put the bandits on their heels momentarily, but they have adapted and actually taken advantage of the situation now. They are communicating via satellite phones with one another while, as a result of cellular networks being down, local communities have lost their ability to communicate with security forces and to update them on imminent bandit attacks. The restrictions on movement are also causing prices to rise and hurting rural communities as a result. The bandits are demanding higher levies to cover their own inflated petroleum costs. This is further impoverishing communities from whom bandits can find new recruits.

The federal government has sent more troops to the region, but they are still severely overstretched with many also deployed in the North East against Boko Haram. The military mostly stays in fortified towns and outposts and rarely goes into local communities where these bandit groups and their leaders are openly known and every child can point them out. The military’s airstrikes often seem to just target cattle herds, scaring and scattering them, which only further impoverishes herding communities. Airstrikes are often futile and dangerous because bandits use rural villages as human shields, meaning it is difficult to isolate them as targets.

Community-based armed groups are becoming a more visible presence in the North West. In response to early episodes of violence, these groups have often indiscriminately targeted and harassed Fulani people and worsened the situation. The heavy-handedness of the Yan Sakai vigilantes (“volunteer guards” in Hausa) against herders was a genesis of the rise of full-time bandit gangs in the region starting in 2011. Many vigilante members talk openly of anti-Fulani sentiment and a sense that there is a Fulani menace to be dealt with harshly. Therefore, the violence of and response to the criminal gangs has the potential to escalate into broader inter-communal conflict.

“One possible model is the Civilian Joint Task Force in the North East, which would help provide a permanent security presence by training, paying, and holding vigilantes accountable to an official action plan.”

The use of volunteer militias to protect communities is understandable because of the thin security presence, but vigilante groups like Yan Sakai are technically illegal, not trained, and unaccountable. The government policies of the states in the North West region have been inconsistent, oscillating between indirectly sponsoring them and banning and condemning them. Powerful political figures are known to use them to settle scores. A consistent and coordinated policy is needed that will curb the abuses of these groups, which are operating as Hausa ethnic militias and are ethnicizing the conflict. One possible model is the Civilian Joint Task Force in the North East, which would help provide a permanent security presence by training, paying, and holding vigilantes accountable to an official action plan.

Amnesty programs have potential because some of the bandit leaders are declaring that they want peace. Coordinated and well-implemented amnesty programs present a pragmatic option because, otherwise, it will be very difficult to vanquish these groups now that many gangs have become entrenched within communities and operate as sovereigns where the state is not present. Past attempts at providing amnesty have failed because they only involved one State and had not been coordinated and seen through to completion. They were handshake deals that crumbled under stress. An on-the-ground military campaign that actually sought to capture and hold bandit leaders accountable coupled with a well-designed amnesty program could begin to yield results.

Additional Resources

- James Barnett and Murtala Rufa’i, “The Other Insurgency: Northwest Nigeria’s Worsening Bandit Crisis,” War on the Rocks, November 16, 2021.

- Idayat Hassan, “Nigeria’s Rampant Banditry, and Some Ideas on How to Rein It In,” The New Humanitarian, November 8, 2021.

- Kunle Adebajo, “Vigilantes Defying the Odds To Protect Lives In Northwest Nigeria,” HumAngle, November 3, 2021.

- Kunle Adebajo, “Displaced By ‘Bandits’ (Parts 1-5),” HumAngle, July 17 – October 12, 2021.

- Leif Brottem, “The Growing Complexity of Farmer-Herder Conflict in West and Central Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 39, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2021.

- Mark Duerksen, “Nigeria’s Diverse Security Threats,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 30, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The Nigerian State and Insecurity,” Video Roundtable, February 17, 2021.

- Olajumoke (Jumo) Ayandele, “Confronting Nigeria’s Kaduna Crisis,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 2, 2021.

More on: Combatting Organized Crime Nigeria Policing