English | Français | Português

A displaced family in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique. (Photo: UNHCR)

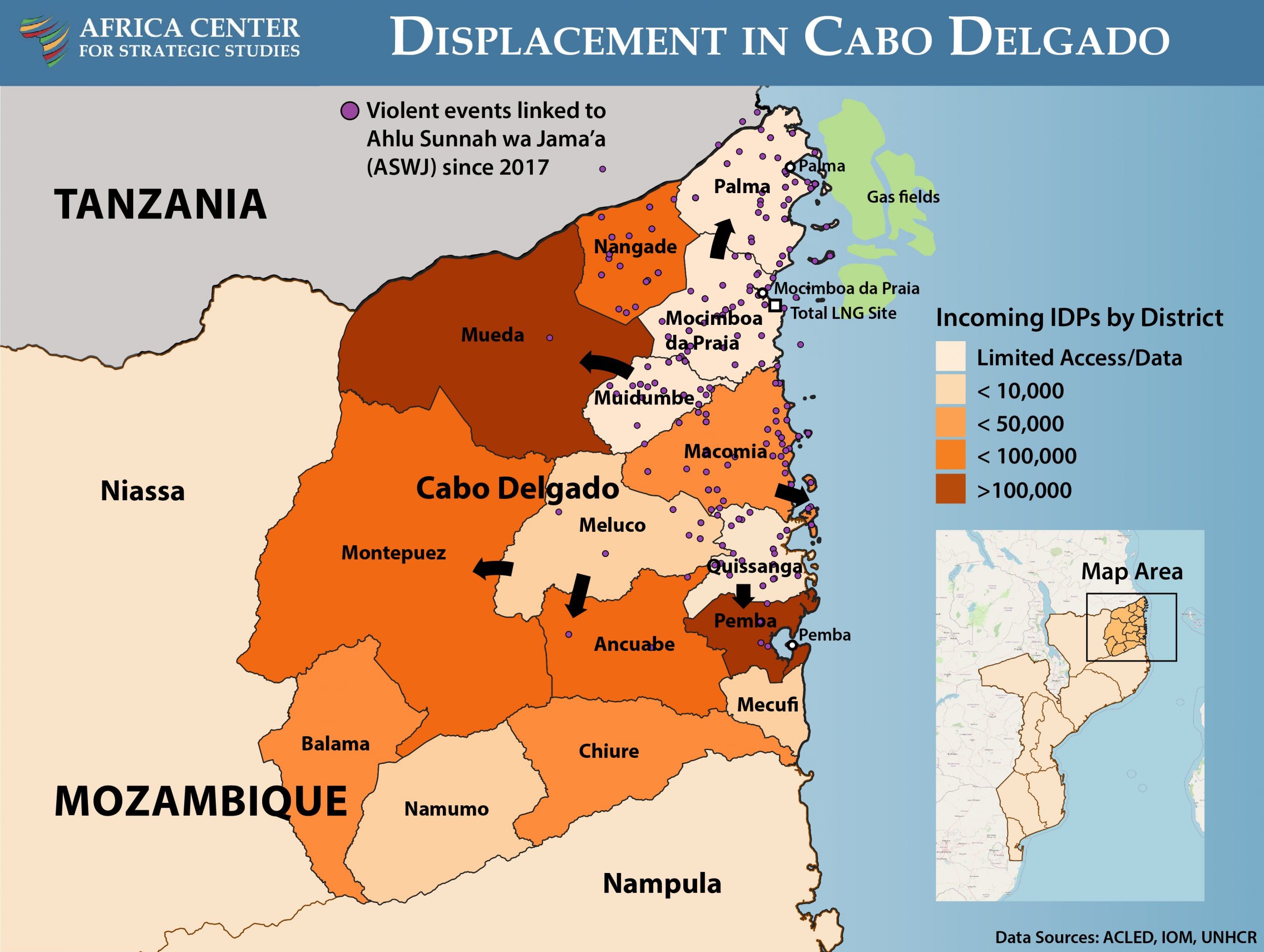

Mozambique’s northernmost province of Cabo Delgado has been plagued by the rise of violent extremism since 2017. More than 3,300 people have reportedly been killed by Ahlu Sunnah wa Jama’a (ASWJ), often in ways intended to shock and terrorize local communities. More than two-thirds of ASWJ violence targets civilians, distinguishing the violent extremist activity in Mozambique even among other militant Islamist groups in Africa. The violence in Cabo Delgado has also generated over 800,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs), out of a total provincial population of 2.3 million.

“The violent extremist threat in northern Mozambique exploits underlying societal vulnerabilities of inequity, insecure land rights, and distrust of authorities.”

The risk of violence in northern Mozambique spreading to other parts of the country and southern Africa has prompted a series of external commitments to assist the Mozambican government in its fight against the insurgency. These include deployments by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), of which Mozambique is a member, a 1,000 member-strong Rwandan force, and training missions by the European Union, Portugal, and the United States.

Rwanda’s deployment to Cabo Delgado followed a meeting among the presidents of Mozambique, Rwanda, and France. France’s largest petroleum company, Total, with an estimated $20 billion investment in Cabo Delgado, was forced to withdraw its personnel, stop its operations, and declare force majeure in April 2021 because of the security situation. Exxon Mobil has also put on hold plans to develop an even larger onshore facility.

Less well recognized is that the violent extremist threat in northern Mozambique exploits underlying societal vulnerabilities of inequity, insecure land rights, and distrust of authorities. An effective response in Cabo Delgado, therefore, will require more than conventional security actions. Understanding the local dynamics that have made this region vulnerable to destabilization will be vital to an effective security strategy.

From the perspective of local communities in Cabo Delgado, the often repeated narrative of the insurgency being part of a global Islamic State-linked threat is a distraction from the true drivers of the conflict and threats posed to local households’ livelihoods, safety, and conditions that would allow those forcibly displaced to return to their ancestral lands.

The crisis in Cabo Delgado starts with a stark trust deficit in government institutions, which are perceived as having long exploited local communities. Restoring the population’s trust in the government and those providing public services—including police, security forces, health care workers, educators, and others—is critical to ending the bloody upheaval. Doing so is essential to undermining the sociopsychological sway that ASWJ holds over the youth who have swelled its ranks.

This analysis draws from interviews with 65 IDPs in relocation settlements in Pemba and Mecúfi Districts. Many described what they have experienced as a kind of genocide. They painfully describe the loss of their sons and daughters, who have been killed or kidnapped by the “machababos” (the youth), the local name for ASWJ members.

A majority of the IDPs interviewed also lamented the loss of their agricultural lands, which they have abandoned due to the violence. These local residents are now left without the means to sustain livelihoods as well as a direct connection to their culturally important ancestral places. These survivors were obliged to settle on lands traditionally held by other people, which has profound implications in the customary socioeconomic caste hierarchy.

“This analysis draws from interviews with 65 IDPs in relocation settlements in Pemba and Mecúfi Districts. Many described what they have experienced as a kind of genocide.”

Many IDPs fear they are becoming epothas (descendants of slaves), limiting their rights to own land. Epothas must work as sharecroppers on the land possessed by others, to whom they must pay a part of each crop as rent. Well into the 19th century, what is now northern Mozambique had been a point for the shipment of slaves to Zanzibar, the Comoros, Somalia, Cape Colony in modern-day South Africa, and beyond. Along the coastal regions, slavery was also an institution. With the ending of slavery, many of these former slaves became sharecroppers.

Being an epotha leaves them without political, social, and land rights. Some of the IDPs fear they are becoming vientes–not quite slaves but owing political allegiance to the donos de terra (the owners of the land) who have lineages to those who first settled on the land.

A History of Suspicion of Authorities

In the stories they tell, IDPs and other community members regard themselves as victims. Within this narrative, both the machababos and the government’s police and military forces, called militares, are the villains for their roles in committing violent acts and corrupt practices. The insurgents are well known for their brutal killings of civilians that include beheadings. Some of the IDPs, furthermore, related instances of the militares raping women and looting stores.

A woman displaced by violence in northern Mozambique. (Photo: UNHCR)

Many of the alleged abuses by militares followed attacks on villages by the insurgents. Human Rights Watch has reported that men found in Cabo Delgado villages by security forces were rounded up and held in military detention without due process. Security forces arriving in villages several hours after an insurgent attack reportedly arrest young men and others who refuse to cooperate with them. These heavy-handed security responses, in turn, are linked to further ASWJ recruitment.

Many of the people interviewed believe that the violence has been deliberately designed to remove them from their lands. Poignantly, in January 2019, escalating machababos attacks and harsh security responses led residents to take to the streets in the city of Palma. Among other grievances, protesters claimed the ASWJ attacks were supported by powerful Mozambican figures to drive local inhabitants off their land. The local communities believe that these politically well-connected actors will then claim possession of and profit from the land, which has been increasing in value due to the vast foreign investments being made in Cabo Delgado to exploit its mineral and petroleum resources.

“Smuggling networks of heroin, rubies, gold, timber, wildlife, and migrants … are a major part of the political economy of northern Mozambique.”

Although there is no known evidence to support this narrative, even Mozambique’s President Filipe Nyusi has claimed, without offering evidence, that certain Mozambican businesspeople likely provide financial support to the machababos to further their business interests. Illicit flows and smuggling networks of heroin, rubies, gold, timber, wildlife, and migrants have been entrenched in Cabo Delgado for decades and are a major part of the political economy of northern Mozambique. Reports suggest that these trafficking routes are shifting outside the insurgent-controlled area, which is highly militarized, limiting the insurgents’ ability to benefit from the illicit economy. Nonetheless, reflecting the criminal motivation behind at least some of the violence, the militants are known to hold some captives for ransom, using mobile phone access and money-transfer apps to obtain payment.

The popular belief in the economic motives for driving the population from their land underscores the local population’s distrust of government, suspicion of Mozambicans from the southern part of the country, and perceptions of unfairness in Mozambique’s land tenure system that leaves them vulnerable to losing their land. Under law, the state is owner of the land and citizens are mere occupants with the right of usage and improvement of land. In practice, according to a USAID assessment, smallholder “land rights remain vulnerable to capture by elites who often enjoy state support on the grounds that they have greater capacity than smallholders to bring unused resources into production. These conditions make it difficult for communities and individual landholders lacking formal land documentation to defend their land rights against third parties, make long-term investments in their land, or meaningfully engage in negotiations with the private sector.”

The machababos take advantage of the population’s sense of social and economic vulnerability. A study based on interviews with 23 females who had experienced ideological indoctrination in insurgent camps found that the machababos’ promise of a messianic social order and the provision of basic benefits—such as food, clothing, and protection from violence—was seductive to a population that is socially and food insecure and exposed to violence.

Steps for Restoring Trust

(Photo: Agenzia Fides)

The most critical action that the Mozambican government can take is to shift its strategic communications narrative to a clear and unambiguous expression that the wellbeing of the people of Cabo Delgado is the government’s primary concern. This narrative shift must be accompanied by concrete development actions and expanded, authentic dialogue with affected communities. Given their perceptions of marginalization, Cabo Delgado communities place great importance on outreach, being heard, reassured, and respected by government authorities at all levels. Seeing the conflict through the eyes of local communities, in turn, is critical for trust building and facilitating the establishment of meaningful and productive community-government engagements.

Such engagements will also help ensure that community-defined priorities are met. Community participatory approaches will also contribute to greater community ownership of economic and development processes, reinforcing a sense of self-efficacy within targeted communities. These techniques are commonly used in the fields of public health, climate change adaptation, resource management, and more. Sincere dialogues with community stakeholders hold the potential for restoring trust in a population that feels neglected and abused, and will potentially help promote a sense of hope in a population traumatized by conflict.

“Sincere dialogues with community stakeholders hold the potential for restoring trust in a population that feels neglected and abused.”

The introduction of greater community oversight of the police is another important step toward lessening corruption and improving criminal justice. Corruption significantly undermines citizens’ trust in political arrangements and reduces citizen willingness to engage with formal policing and justice systems. Perceived corruption in the security and justice sectors has a particularly debilitating effect on public trust. Violent crime and conflict in such contexts are more likely.

Because of the widely reported human rights violations carried out by Mozambique’s Defense and Security Forces and the police’s elite Rapid Intervention Unit, all security training provided by the international community needs to incorporate effective human rights components. These training interventions should include monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to ensure that meaningful outcomes are achieved, and if not, that corrective actions are taken to ensure that human rights are respected.

Additional Resources

- Richard Poplak, “IS-Land: Has the Age of Southern African Terrorism Properly Begun?,” The Daily Maverick, May 4, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Spike in Militant Islamist Violence in Africa Underscores Shifting Security Landscape,” Infographic, January 29, 2021.

- Francisco Almeida dos Santos, “War in Resource-Rich Mozambique—Six Scenarios,” CMI Insight, No. 2, Chr. Michelsen Institute, May 2020.

- Gregory Pirio, Robert Pittelli, and Yussuf Adam, “The Many Drivers Enabling Violent Extremism in Northern Mozambique,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 20, 2019.

- Stephen Commins, “From Urban Fragility to Urban Stability,” Africa Security Brief, No. 35, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 2018.

More on: Countering Violent Extremism Extremism Governance Mozambique