An AMISOM field commander in front of an armored personnel carrier.

In 2017, Somalia held parliamentary and presidential elections in a relatively stable atmosphere. The African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM), which has been deployed to Somalia since 2007, has been a key factor in realizing this milestone. Nonetheless, al Shabaab, the militant Islamist group that has been destabilizing Somalia, remains a serious threat. The Africa Center for Strategic Studies spoke to Simon Mulongo, the Deputy Special Representative of the Commission Chairperson to Somalia (D/SRCC) at the African Union Commission based in Mogadishu to gain a perspective on the state of the mission.

What are some key lessons that AMISOM has learned over the course of the last decade?

Although AMISOM is often called a peacekeeping or peace enforcement mission, in fact, AMISOM is a combat mission fighting a terrorist insurgency in Somalia. When it first deployed to Somalia in 2007, Islamist militants controlled most of Somalia and large swaths of the capital, Mogadishu. AMISOM’s first task was to push al Shabaab out of the capital and create conditions in which the Transitional Federal Government could operate. It initially used a traditional peacekeeping approach: staying encamped, conducting limited patrols, and returning fire only when fired upon. This model was quickly abandoned when al Shabaab began launching attacks on the AMISOM encampments. In 2011, AMISOM began an operation that dislodged al Shabaab from Mogadishu’s central business district and flushed them out of the country’s main supply routes and regional centers. By 2017, al Shabaab had been expelled from most of its strongholds in southern Somalia. Along the way, AMISOM troops took significant casualties.

Al Shabaab fighters surrendering to AMISOM forces in September 2012.

AMISOM’s gains in the field could never have been realized if it had continued to rely on the traditional peacekeeping template. Ours is probably the deadliest mission of its kind anywhere in the world, and our troops and civilians have had to adapt, through trial and error, to the unique challenges of the Somalia context. Initially, we expected AMISOM to eventually transition to a hybrid UN/AU mission or a full UN mission, following the model of the African Mission in Darfur, Burundi, and others. This could not happen in Somalia because the environment has remained extremely fluid. Across Africa, peacekeepers are increasingly being deployed to highly fragile political and security environments, and the main challenge will be to adapt existing doctrines to reflect this reality. AMISOM’s experience offers valuable lessons in this regard.

What are the main challenges and constraints facing the mission?

Al Shabaab uses a complex mix of conventional warfare tactics in combination with urban warfare, guerrilla warfare, and terrorism. In September 2017 for instance, al Shabaab fighters used car bombs and coordinated mortar attacks to overrun a Somali army base, killing eight soldiers. Two weeks later, they carried out a devastating bombing in the center of Mogadishu, involving a truck packed with 600 kilograms of highly sophisticated and homemade explosives. In November, al Shabaab militants ambushed a convoy carrying a regional governor in central Somalia, killing two soldiers. No explosives were used in that attack. In January, they killed 38 people in two car bomb blasts followed by heavy rocket and mortar fire outside the presidential palace. This ability to employ and deploy different tactics and capabilities in successive waves of attacks shows that al Shabaab is highly adaptive and resilient.

The other challenge AMISOM faces is in the area of logistics and supplies. The United Nations Support Office for Somalia (UNSOS) is only authorized to transport non-lethal assistance and troops to designated points known as battalion hubs. The transportation of war supplies and the onward transfer of troops from the battalion hubs to the field is the responsibility of the troop-contributing country.

A Kenyan Air force helicopter landing in southern Somalia.

However, AMISOM’s airlift capabilities are minuscule: it has only three utility helicopters to cover its entire area of operation—400,000 square kilometers. While there have been offers of additional aerial assets, the rate at which the UN reimburses countries willing to supply and maintain them is said to be low, making it less attractive for them to put these vital capabilities at our disposal. Logistics are therefore unreliable and erratic, and our troops are therefore overstretched and unable to secure the expansive territory and protect their supply lines.

Attempts to improve AMISOM’s supply system have also been hampered by the incompatibility of doctrine. UNSOS supply capabilities are civilian, not military. As such, they are structured to provide logistics in a traditional peacekeeping mission and not for a combat environment. Strict restrictions on where UNSOS air assets can land, for instance, have made the evacuation of our troops extremely difficult.

AMISOM operates in a “contingent-centric” environment where everything—from troop deployment to equipment—is mainly controlled by the troop-contributing country and not the mission. As a result, force commanders do not have complete leeway to direct their own forces, which can delay or even hamper operations.

“Al Shabaab has much better access to intelligence than AMISOM.”

Additionally, AMISOM lacks force enablers and force multipliers. A force enabler is a capability such as transportation or communications that contributes to the success of a mission. A force multiplier, on the other hand, is a combination of capabilities that greatly increase military effectiveness, such as combat aircraft, infantry fighting vehicles, and heavy artillery. AMISOM still lacks the requisite force enablers and multipliers to effectively deliver on its mandate. This hampers its ability to hold liberated areas.

Finally, al Shabaab has an intelligence arm that it uses to collect information from the population under its control. It relies on this, as well as its knowledge of the local culture and language, to sustain itself.

How would you characterize the progress made in building the Somali National Army (SNA)?

Efforts to build the Somali National Army date back to 2007. The SNA’s core weakness stems from the collapse of the Somali government in 1991 when the military splintered along clan lines. Today, rival clans are the primary sources of recruits and clan divisions remain pervasive in the force. The government’s 2017 Operational Readiness Assessment lays bare the logistical, financial, and operational gaps facing the military. Among other things, it found that 30 percent of soldiers in the bases do not have weapons. Furthermore, the army lacks vehicles, communications, and shelter. Very little has been done to address the report’s findings.

Training for the SNA is mainly provided by Turkey, the United States, and United Kingdom. A United Arab Emirates (UAE) program that had trained and paid some SNA troops since 2014 was recently halted after a dispute between the government and the UAE.

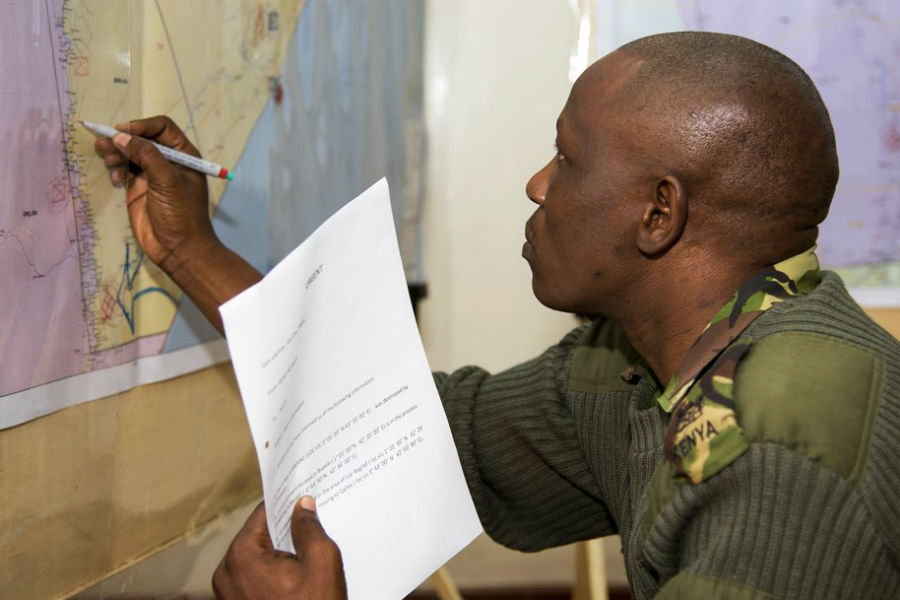

A Kenyan soldier plotting troop movements on a map during an Africa Contingency Operations Traning and Assistance (ACOTA) training course.

About 800 soldiers finish their training each year under the Turkish, U.S., and UK programs. This number is too low for the force generation required for the SNA to be able to conduct effective operations. Somalia needs about 50,000 well-trained troops if it is to take over its own security after AMISOM leaves in 2020, according to the recently approved Transition Plan. Additionally, the training is not coordinated, and the partners have not developed common standards, doctrine, and curricula. The SNA will require a professional and well-developed officer corps with the leadership, discipline, and equipment that coordinated training is meant to achieve.

What non-military tasks does AMISOM undertake and how do they support the mission’s larger goals?

When we began dislodging al Shabaab from its strongholds, the population came to our bases in droves seeking medical attention, food, and security in their areas, and even assistance in solving disputes. It became clear to us that al Shabaab’s residual popular support in many of these communities was due to the semblance of order and services it provided. Communities tolerated them because public services were nonexistent after the state collapsed in 1991, and there was a general state of lawlessness where warlords preyed on the population with impunity. The Ugandans, who, in 2006, were the first troops to deploy to Somalia, stepped in to provide medical doctors and veterinarians to meet some of the needs before AMISOM was created in 2007. However, this became untenable and diverted troops away from their core tasks. That is when we prioritized the need to develop a strong civilian component as a critical part of the overall mission.

Today, AMISOM deploys about 70 civilian peacekeepers at the community level to support the local population. From their headquarters, they are routinely required to undertake a range of activities, including political affairs, gender mainstreaming, public information dissemination, counter propaganda, legislative reform, and security sector reform. All these are aimed at developing the government’s capacity to deliver services and consolidate its local support. UNSOS’ civilian component is estimated to include about 500 people but operates mainly in Mogadishu and some regional centers due to security restrictions. AMISOM staff, on the other hand, operate more freely and have greater access in the field. There is a need for the AU and UN to work more closely together to better leverage UNSOS’ superior resources and AMISOM’s flexibility to enhance our civilian work.

How do you see the future of the mission changing, and what does success look like?

“The lack of predictable financing has compelled the AU to endure the consequences of partners whose interests and priorities may not always be in tandem with those of the region.”

AMISOM was founded in the spirit of resolving African problems using African solutions. The Somali government needs to become efficient and accountable to its people. It can only do that if it commits itself to pursuing local development rather than remaining reliant on foreign assistance. On the military side, AMISOM requires more support to address its operational and logistical needs. The AU’s quest to access assured and predictable sources of funding remains a major challenge. The continental approach to addressing conflicts coupled with the willingness of African countries to put their professional and dependable troops in harm’s way should be steadfastly supported by the UN. This is because in situations like Somalia the AU is carrying the burden of the UN Security Council, which is the custodian of international peace and security. The lack of predictable financing has compelled the AU to endure the consequences of partners whose interests and priorities may not always be in tandem with those of the region.

The current drawdown of AMISOM force levels has been criticized by troop contributing countries as counterproductive given the increased threat level in a huge operational area. There is a fear that the planned annual reduction that started in December 2017 may compromise the gains made so far and even lead to the mission’s defeat. For the current transition strategy to succeed AMISOM needs to partner with credible, professional, and capable Somali security forces that are loyal to a democratic, accountable, and legitimate government. Some progress has been made in these areas, but there is still a long way to go.

Additional Africa Center Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “African Militant Islamic Groups Still on the Rise,” Infographic, April 27, 2018.

- Abdisaid M. Ali, “Islamist Extremism in East Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 32, August 9, 2016.

- Daniel Hampton, “Creating Sustainable Peacekeeping Capability in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 27, April 30, 2014.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,”Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Research Paper No. 6, July 2014.

- Michael Olufemi Sodipo, “Mitigating Radicalism in Northern Nigeria,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 26, August 31, 2013.

- Paul D. Williams, “Peace Operations in Africa: Lessons Learned Since 2000,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 25, July 2013.

More on: Stabilization of Fragile States Al Shabaab AMISOM Somalia