Burundi police pursuing demonstrators protesting the third term of Pierre Nkurunziza in April 2015. (Photo: VOA)

The passage of Burundi’s controversial May 2018 referendum to alter nearly a third of the 2005 Constitution’s articles put the ruling CNDD/FDD party on the cusp of a long sought-after goal: to overturn the 2000 Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement.

Mediated by former Presidents Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Nelson Mandela of South Africa, the Arusha Accords ended the cycles of violence Burundi experienced from the 1960s through the genocides of 1972 and 1991 and the 1993–2005 civil war. The Accords built in systems that ensured the respect of political minorities, power sharing among parties, and inclusive governance. By abolishing these systems, the CNDD/FDD has tightened its control of the state apparatus and done away with mechanisms designed to hold it accountable. It will now rule virtually unchallenged.

The East African Community, which has been chairing peace talks on Burundi, along with the multilateral guarantors of the Arusha Accords, did not send observers to the referendum.

The East African Community (EAC), which has been chairing peace talks on Burundi, along with the multilateral guarantors of the Arusha Accords—the African Union (AU), European Union (EU), and United Nations (UN)—did not send observers to the referendum. This, and the fact that the referendum was held despite the displacement of over 500,000 Burundians, who could not participate in the vote and almost all of whom felt threatened by the government, raise questions about the referendum’s legitimacy.

Additionally, the climate of intimidation and violence made it an unbalanced contest. The parties that remain in Burundi’s internal opposition largely stayed away from the referendum process and accused the government of massive voter intimidation. At the launch of the referendum campaign in December 2017, President Pierre Nkurunziza threatened to “correct” those who opposed the exercise. “Any person who stands against this… will have to contend with God.… But I know some people are deaf to these messages. Let them try.” In similar fashion, Désiré Bigirimana, administrator of the Gashoho municipality, was quoted at a rally in February as saying, “Anybody who will come and tell you anything other than a ‘yes’ to the referendum, or different from what President Pierre Nkurunziza says, should be lynched. Is that clear?”

Throughout the campaign and during voting, the CNDD/FDD’s ethnically based youth militia, the Imbonerakure, informed on real or perceived opponents, harassed the population, conducted illegal police operations, and forced recruitment into the ruling party through, in several cases, torture. This was corroborated by eyewitness interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch, which also documented scores of abuses committed between December 2017 and March 2018, including abductions, rapes, and killings by members of the police and intelligence, military, and the Imbonerakure. These atrocities extended across borders where Burundian refugees have been surveilled, threatened, abducted, and killed in some cases, by individuals suspected of being members of the Imbonerakure. The worst episode of violence occurred a week before voting, when unidentified gunmen massacred at least 24 people in a village in northwest Burundi.

Members of the Imbonerakure, the armed youth wing of the CNDD-FDD.

Worries about the credibility of the referendum had been building for some time. In early May, the Chairman of the AU Commission, Musa Faki, wrote to EAC Chairman and mediator of the stalled inter-Burundian dialogue, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, warning that the referendum would deepen Burundi’s crisis. Similar warnings were delivered by the EU, UN, and AU.

A legal challenge to the referendum was thrown out by the Constitutional Court, which has been packed with Nkurunziza’s loyalists since its vice president was forced into exile in 2015 for refusing to endorse the president’s decision to run for a third term in office. The constitutional changes called for in the referendum took effect on June 6. Explosions and gunfire now occur with greater frequency. Local monitors have documented more disappearances and killings since the new laws were enacted, including beheadings and bodies dumped in public places, some of them with hands tied. Attacks on civilians by the Imbonerakure have continued, including one in mid-June that resulted in the deaths of eight civilians. Burundians continue to flee the worsening violence, adding to the nearly 500,000 citizens who have sought refuge in neighboring countries and 175,000 who have been internally displaced. The EAC peace talks remain suspended and the guarantors of the Arusha Accords are pondering their next steps.

How the Results of the Referendum Weaken the Arusha Accords

The referendum revised 90 out of 307 articles in the 2005 Constitution, affecting protocols of the Arusha Accords that put in place mechanisms to prevent genocide, safeguard democracy, and ensure security. Under those rules, constitutional revisions could only be passed with the consent of four-fifths of the National Assembly and two-thirds of the Senate, majorities that the ruling party failed to garner in 2014 and 2015. Arusha put these controls into place specifically to ensure that the governing party did not use its majority to dominate the other arms of government. However, the CNDD/FDD was able to bypass them by putting its amendments to a referendum whose outcome it could control.

The changes give the CNDD/FDD full control of the executive branch

The changes give the CNDD/FDD full control of the executive branch, granting it new powers to pass laws without risking possible legislative resistance, removing the safeguards that allowed for greater participation and representation of political and ethnic minorities, and weakening checks and balances.

Presidential directives now supersede parliamentary rules, contrary to provisions of the Arusha Accords that ensured independence of the legislative branch. Moreover under the new constitution any bill passed by parliament automatically becomes null and void if the president does not assent to it in 30 days. As a further demonstration of executive domination a presidential order decreed after the referendum that parliament only needs a simple majority to pass constitutional revisions, amend laws, approve members of the electoral commission, and change electoral rules. Indeed parliament passed all the constitutional changes through a simple majority as directed by an executive order. The constitutional amendments further reduce the vibrancy of the legislative branch by requiring minority parties to secure 5 percent of the national vote to gain representation in parliament, up from the 2 percent threshold written into the Arusha Accords to give smaller parties a stake in the political process.

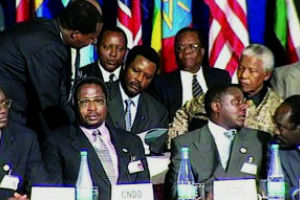

The signing of the Arusha Accords

The Arusha Accords also encouraged independent caucusing, a tool that allowed independents to form inter-ethnic coalitions as a means to promote principled political competition. Such caucuses were a novel feature of Burundi’s political system through which citizens could participate in the political process on the basis of individual merit as opposed to membership of a political party. They became a popular alternative to Burundi’s traditional parties and took the form of coalitions that appealed to younger voters. All of Burundi’s existing independent coalitions are multi-ethnic, which has helped to promote reconciliation over time. The new constitution, however, imposes stiff new conditions on independent caucusing. Individuals are now required to sever all political ties and wait three years and submit proof that they have done so before forming coalitions. The government’s main opponents, all of whom operate as multi-ethnic coalitions, will be automatically disqualified from the 2020 polls by this provision. The rule also bars people with dual citizenship from contesting elections, even if they renounce their second nationality. This rule will disqualify exiles, including delegates that participated in the EAC-led peace talks, as well as potential challengers within the CNDD/FDD.

The 2005 Constitution required ethnic quotas in government and the military to balance Hutu and Tutsi representation (63 percent Hutu to 33 percent Tutsi in parliament, 67/33 in the executive branch, and 50/50 in the military. These quotas were not changed in the new constitution, but they have been rendered inoperable by the removal of the Arusha Accords’ four core safeguards: legislative vetoes, parliamentary thresholds, modalities for balanced and inclusive representation, and rules on proportionality. Under the Arusha Accords, and the 2005 Constitution, the quotas were allocated and enforced through these rules. Now that they have been removed, the numbers and percentages that are supposed to constitute these quotas will now be determined by presidential directive. This will encourage patronage as alignment to the government will be a criterion on which quotas will be allocated. Moreover the CNDD/FDD-controlled parliament has been granted new powers to review them every five years.

What to Expect Next

Burundi’s reconfigured governing landscape reinforces the repression that has triggered the political crisis that has persisted since April 2015, when Nkurunziza announced that he would pursue a third term. Language in the constitution that forbade restrictions on the bill of rights was removed, police searches without a warrant are now permitted by law, and clauses providing for the surrender of persons indicted for crimes against humanity have been removed.

The provision for two vice presidents, one from the ruling party and the other from the opposition, has been replaced with one weak vice president from the opposition and a powerful prime minister from the ruling party. Under the Arusha arrangements, the executive office consisted of a president and two-co equal vice presidents, one from the president’s party, and the other from the opposition. Under the new governing arrangements the president will select a powerful prime minister from his party and a weak and largely ceremonial vice president from the opposition. The creation of a prime minister is widely seen as an attempt to accommodate rivals for the presidency in the CNDD/FDD but it merely formalizes the imbalance in power that occurred when Burundi’s two vice presidents fled the country in 2015. With the ruling party now firmly in the control of the executive, presidential terms have been increased to seven years, allowing Nkurunziza, who has been in power since 2005, to seek re-election in 2020 and 2027.

Burundi’s spiraling crisis also extends to the military, whose reform was once seen as a success of the Arusha Accords. A major purge of members of the military who were perceived to oppose Nkurunziza’s efforts to sidestep constitutional term limits was undertaken, causing waves of defections, tit-for-tat assassinations, and even shootings inside military facilities. Many defectors have joined rebel groups battling government forces.

Burundi’s spiraling crisis also extends to the military, whose reform was once seen as a success of the Arusha Accords. A major purge of members of the military who were perceived to oppose Nkurunziza’s efforts to sidestep constitutional term limits was undertaken, causing waves of defections, tit-for-tat assassinations, and even shootings inside military facilities. Many defectors have joined rebel groups battling government forces.

In a bid to further enforce loyalty within the ranks, ex-civil war commanders now dominate the CNDD/FDD’s supreme body, the Council of Elders, as well as the National Security Council and defense ministry. These party loyalists, many of them under EU, UN, and U.S. sanctions, do not hold formal positions in the civil service but operate parallel chains of command bypassing the defense ministry, and running into the presidency. Through them, instructions are issued to the Imbonerakure, and other parts of the state’s coercive machinery such as the intelligence and police, according to UN reports. This overt politicization has been reinforced by amendments that rename the army, reorganize its command, and create a reserve force that many fear could incorporate the Imbonerakure. This militia is now central to the regime’s security operations and implicated in serious human rights violations according to AU and UN investigators.

There are also ethnic undertones in the regime’s purges, as they target the mainly Tutsi members of the former Armed Forces of Burundi (FAB). This is despite the fact that many of those opposed to a third term for Nkurunziza were Hutu members of the former Parties and Armed Movements (PMPA), which is dominated by the CNDD/FDD. The continued politicization of the army matters greatly because Burundi’s stability between 2005 and 2015 was largely underpinned by military professionalism, balanced representation, and a widely held view that the army was independent enough to resist being manipulated by politicians. This was on display during the protests against the third term when soldiers protected civilians by positioning themselves between protestors and the Imbonerakure and police. However, since the purges, the military has steadily shifted away from its apolitical posture, a trend that is likely to continue as the new constitutional provisions take hold.

What’s at Stake

At the EAC summit in May 2017, Benjamin Mkapa reminded the attendees about the dangers of revising Burundi’s constitution: “Whither the EAC-led mediation whose dialogue I am facilitating? For I fear the region will find itself before a fait accompli.”

The stakes couldn’t be higher as the window for compromise shuts and guarantors of the Arusha Accords ponder their next steps. The credibility of the EAC and AU is at risk, given their failure to enforce the agreement when its provisions were being flouted. This in turn raises further questions about regional and continental commitments to “African solutions to African problems” and the rationale of the African Peace and Security Architecture.

Further moves to revive the peace talks will now have to address the implications of the dismantling of the Arusha Accords and the negative effects on Burundi’s political process. The restoration of these accords, with stronger safeguards and renewed enforcement by the guarantors, remains the least costly path to realizing peace in Burundi.

Africa Center Experts

- Paul Nantulya, Research Associate

Additional Resources

- International Crisis Group, “Burundi’s Dangerous Referendum,” Commentary, May 15, 2018.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Term Limits for African Leaders Linked to Stability,” Infographic, February 23, 2018.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Dismantling the Arusha Accords as the Burundi Crisis Rages On,” Spotlight, March 13, 2017.

- Thierry Vircoulon, “Insights from the Burundi Crisis I: An Army Divided and Losing Its Way,” International Crisis Group, October 2, 2015.

- Nicole Ball, “Lessons from Burundi’s Security Sector Reform Process,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 29, November 30, 2014.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Research Paper No. 6, July 31, 2014.

More on: Democratization Regional and International Security Cooperation Security Sector Governance Burundi Ethnic Conflict Governance Rule of Law