African Union Commission Chairperson H.E. Moussa Faki Mahamat gives a speech during the 5th mid-year coordination meeting of the African Union at the United Nations offices in Nairobi. (Photo: Simon Maina / AFP)

During the United Nations General Assembly’s 2023 budget negotiations, China, Russia, and aligned countries—including several from Africa—proposed defunding the UN Human Rights Council’s (HRC) investigations in seven countries, including Eritrea, North Korea, Nicaragua, and Russia itself. China proposed defunding investigations of Myanmar, while Russia did the same for its ally Syria. Taking a cue from this effort, Ethiopia introduced a proposal to defund the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia, drawing a rebuke from 63 African human rights organizations and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR).

In recent years, the International Criminal Court has encountered similar resistance from a number of countries, big and small.

China is increasingly relying on governments from Africa and the Global South to support China’s quest to build a new global architecture and selectively reshape parts of the existing system. In 2017, all 11 African HRC members helped pass a Chinese-sponsored text that introduces “noninterference,” “quiet dialogue,” and “state-led development” as an alternative framework for human rights. Seventeen Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latin American countries voted alongside China, Russia, and the “African 11” to adopt the proposal by a margin of 30 votes “for” to 13 “against,” with 3 abstentions.

A weakened UN would be detrimental to Africa.

In 2020, all but one African HRC member voted for another Chinese resolution that inserted elements of “Xi Jinping Thought” into UN language. Xi Jinping Thought draws on a compendium of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) policies including collective rights as opposed to individual rights and an emphasis on “dialogue and cooperation” with affected states as opposed to investigations when human rights violations have been raised in the HRC. NGO and civil society coalitions—including many from Africa—referred to this policy in a terse statement pointing to critical flaws in the Chinese-sponsored text which they said would fundamentally weaken the UN’s global human rights architecture.

Besides its ongoing efforts to introduce norm-altering resolutions in UN bodies, China has also embarked on creating parallel multilateral organizations—part of what it calls to “take a vigorous part in leading the reform of the global governance system” (jiji canyu yinling quan qiu zhili ti xì gaige, 积极参与引领全球治理体系改革). Under this guidance, China is pursuing a two-pronged strategy of increasing its participation in existing international institutions (including its influence over the operations and norms), while creating parallel multilateral institutions. Since the early 2000s, China has created 17 new international bodies.

African countries have joined many of these institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRFIC), and the Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC).

There have also been more direct efforts to undermine the UN. This is seen by an alarming spike in Russian disinformation targeting UN peacekeepers in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Mali that have endangered mission personnel—the vast majority of whom come from Africa and the Global South. For years Russia has actively tried to undermine the UN-backed government in Tripoli, including by deploying Russian paramilitary forces from the Wagner Group and sponsoring the primary disruptor to the UN efforts in Libya, warlord Khalifa Haftar. Russia has refused to withdraw its forces from Libya despite repeated requests from the UN to do so.

Seven Decades of Strategic African Engagement at the UN

The United Nations is the only truly global organization with the mandate and profile to assist in solving pressing global problems. The Global South, where it draws most of its membership, has a special interest in preserving it, despite its shortcomings. Representing 85 percent of the world’s population, countries in the Global South comprise the poorest, least developed, and most conflict-affected areas of the world.

Engagements in these countries from the UN and other multilateral institutions, therefore, are disproportionately influential. This is especially the case with African countries.

African members are among the most steadfast supporters of the UN and favor institutional reforms to make it a more effective, equitable, and inclusive international system.

African members are among the most steadfast supporters of the UN and favor institutional reforms to make it a more effective, equitable, and inclusive international system. Historically, African countries have used their representational strength as the largest single voting bloc to resist efforts to weaken, undermine, or dilute the UN. Rather, they have tried to preserve the integrity of the UN system, address its shortcomings, and make it more responsive to African and Global South concerns.

Apart from Egypt (which became independent in 1922) and Ethiopia and Liberia (which were not colonized), African countries had no role in creating the current rules-based international order. However, they all joined the UN almost as soon as they won their freedom. Universal African membership to the UN was followed by the growth in representation of African NGOs and civil society observers in its various organs. African countries, moreover, did not forget the role the UN played in the fight against colonialism and apartheid.

Left: South African President Nelson Mandela shakes hands with UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali in 1994 before addressing the UN General Assembly in New York. (Photo: Jon Levy / AFP). Right: Former Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan speaking with the media at the United Nations Office in Geneva in 2012. (Photo: United States Mission Geneva)

By the mid-2000s, African countries were an integral part of the UN. They had supplied it two Secretaries-General: Egypt’s Boutros Boutros-Ghali and Ghana’s Kofi Annan. They also became the “center of gravity” for UN peacekeeping and operations—supplying over 70 percent of the world’s roughly 100,000 peacekeepers. Thirteen African countries are in the world’s top 20 troop-contributing countries while half of the UN’s 12 ongoing missions are in Africa.

By virtue of their troop contributions, African countries have helped create new policies, doctrine, and procedures for UN peacekeeping. They played an instrumental role in the discussions leading to “An Agenda for Peace” (1992), the “Supplement to An Agenda for Peace” (1995), and the “Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations” (2000), (also called the Brahimi Report, after the Algerian diplomat who chaired it). These documents provide a blueprint for the current UN peacekeeping doctrine and practice.

African countries helped create the rules that govern the current international system.

African countries also helped create the rules that govern the current international system. Key pieces of international law like the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) would not have come into force without African participation. One of the most significant and distinctively African contributions to UNCLOS is the exclusive economic zone concept—an area of the sea to which a state has special rights including the exploration of marine resources.

It should also be recalled that the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court (ICC) was created through vigorous African advocacy and leadership, leading some like the late anti-apartheid leader, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, to say that the ICC “could not be more African if it tried.”

Since 2010, African professionals have constituted a plurality of the UN’s staff, representing 35 percent of the total workforce. This is followed by Asia, Europe, the Americas, and Oceania. Africa has 22 senior UN leaders, ranging from department heads to special advisors and envoys. African diplomats lead 4 of the 15 UN specialized agencies.

Peacekeepers help protect civilians and their property southwest of Gao in Mali during Operation FRELANA in 2017. (Photo: United Nations Peacekeeping)

African countries receive many benefits from the UN in exchange for their contributions. Much of the work of the UN’s development-oriented agencies like the UN Development Program (UNDP), UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), World Health Organization (WHO), and Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), occurs in Africa. Africa hosts the UN Environment Program (UNEP) in Nairobi—one of only three headquarters-level UN offices outside New York (the other two are in Vienna and Geneva). Thanks to African lobbying, the UN has created numerous special offices dedicated to Africa, like the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) in Addis Ababa. Nearly every African country, meanwhile, hosts a UNDP Representative Office, making the UN an active partner in addressing the continent’s development problems.

African governments are continuously being reminded by their citizens not to lose their focus on creating a fairer global system even while diversifying their partnerships. Many have advocated for clearly defined African strategies of external engagement, particularly in an environment of intensifying global rivalries.

Africa’s common position on international system reform places emphasis on improving the UN’s capacity to independently investigate human rights abuses and a stronger commitment to the Responsibility to Protect principle.

African members have championed a broader interpretation of human rights that includes social, cultural, and economic rights. They also support a robust investigative machinery at the UN. Indeed, the 2005 “Ezulwini Consensus”—Africa’s common position on international system reform—places emphasis on improving the UN’s capacity to independently investigate human rights abuses and a stronger commitment to the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) principle that permits intervention to stop mass atrocities without the host nation’s consent. Some of Africa’s reform priorities for the UN set forth in the Ezulwini Consensus include:

- Enhancing the UN’s capacity to tackle development issues, intrastate conflicts, unconstitutional changes of government, and terrorism.

- Prioritizing the Responsibility to Protect (R2P).

- Defending the UN Charter from abuse by powerful members, particularly with respect to the crime of aggression.

- Strengthening the UN’s General Assembly, Human Rights Council, and Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).

- Expanding the UN Secretariat to increase African participation.

- Inviting Africa to send two permanent, veto-wielding members to the UN Security Council along with five non-permanent representatives.

Efforts to undermine the UN simultaneously set back these reform priorities. Given all the other ways the UN is engaged in Africa, a weakened UN would be detrimental to Africa.

Keeping Focus on African Interests

African countries remain committed to creating a more equitable, inclusive, and effective international order. They view the UN as the most important actor to achieve such an order. While this remains a work in progress—characterized by achievements, setbacks, and institutional inertia—African countries have not abandoned their three-pronged strategy of increasing their participation and representation, diversification, and comprehensive institutional reform.

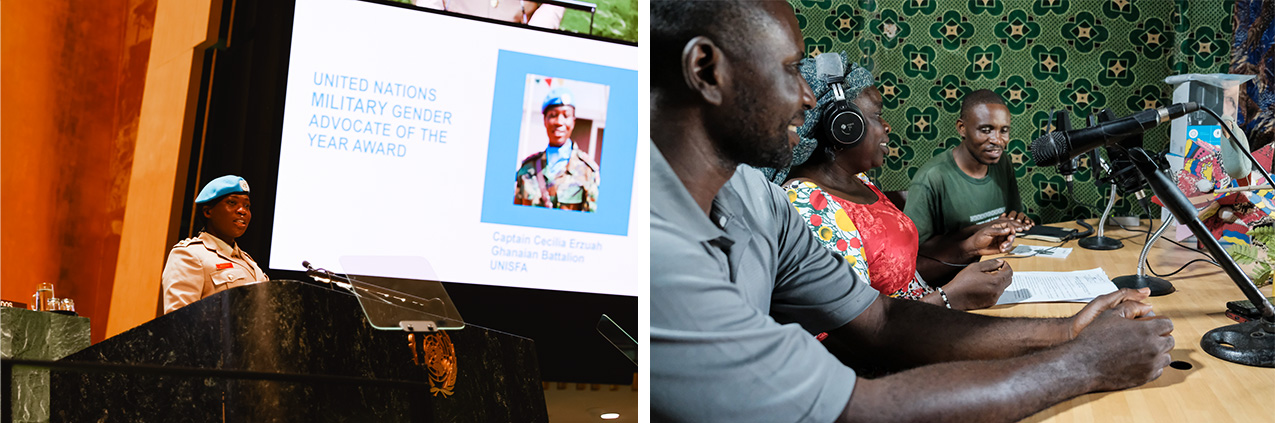

Left: Captain Cecilia Erzuah of Ghana, recipient of the Military Gender Advocate of the Year Award, speaks on the International Day of United Nations Peacekeepers (29 May). (Photo: United Nations Peacekeeping). Right: Awareness campaign on Radio Okapi, a station supported by the United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUC). (Photo: CIFOR)

While rising powers like China and others offer African countries some opportunities to advance their interests on the global stage, Chinese interests and activities do not always neatly converge or even agree with Africa’s global vision. It is therefore imperative that African countries not lose sight of their interests even as they expand their engagements with a range of international actors.

African countries can balance and defend their longstanding principles and commitments in preserving the UN if they maintain a clear strategy building on a body of conventions, norms, and common positions that the African Union has articulated since the 1960s. Navigating this path should not be left to states alone. African civil society has a critical role to play in articulating and implementing this vision given their expanding observer status role at the UN and the unique space they fill connecting African communities to international bodies.

Additional Resources

- Stewart Patrick, ed., “UN Security Council Reform: What the World Thinks,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 28, 2023.

- Joseph Siegle, “Russia and the Future International Order in Africa,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 11, 2022.

- Paul Nantulya, “Africa’s Role in China’s Multilateralism Strategy,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 24, 2023.

- Albert Trithart, “Disinformation against UN Peacekeeping Operations,” Issue Brief, International Peace Institute, November 2022.

- Philani Mthembu and Faith Mabera, eds., Africa-China Cooperation: Towards an African Policy on China?(London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021).

- Isabelle Badza and Sadiki Maeresera, “The Ezulwini Consensus and Africa’s Quagmire on United Nations Security Council Reform: Unpacking the Dynamics,” AFFRIKA Journal of Politics, Economics and Society 9, Special Issue 1, July 2019.

- Ted Piccone, “China’s Long Game on Human Rights at the United Nations,” Brookings Institution, September 2018.

More On: Peacekeeping China in Africa Russia in Africa