Download Full Report

Table of Contents

The results from the survey reveal a number of notable findings that provide insights into the current attitudes, challenges, and perceptions of African security sector professionals and how these are evolving.

Age and Education

An initial striking observation from the survey data is that younger recruits are joining the security services with more advanced education levels. Just 26 percent of respondents in the youngest cohort, for example, entered service with a high school diploma as their highest level of educational attainment. This compares to 47 percent among those in the oldest cohort, reflecting a major shift in academic capabilities within the services in recent decades. Among young recruits, 41 percent entered service with a bachelor’s degree.[1] By contrast, only 30 percent of the oldest cohort had attained a bachelor’s degree when they began their careers.

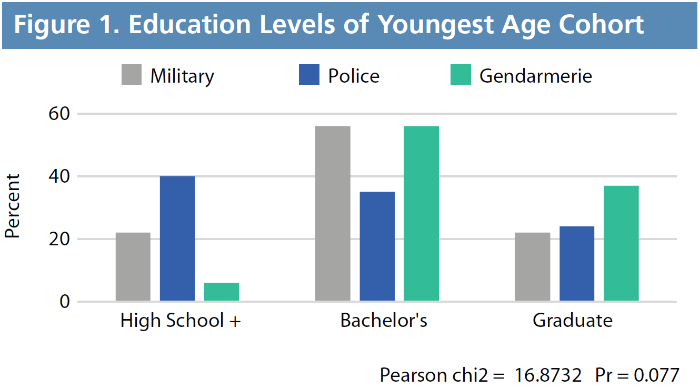

Differences in education level also emerged between services. Recruits from the youngest cohort who joined the gendarmerie and military started their service with considerably higher education levels than the police (see Figure 1). Specifically, 56 percent of recruits from the gendarmerie and military had a bachelor’s degree versus 35 percent for the police.

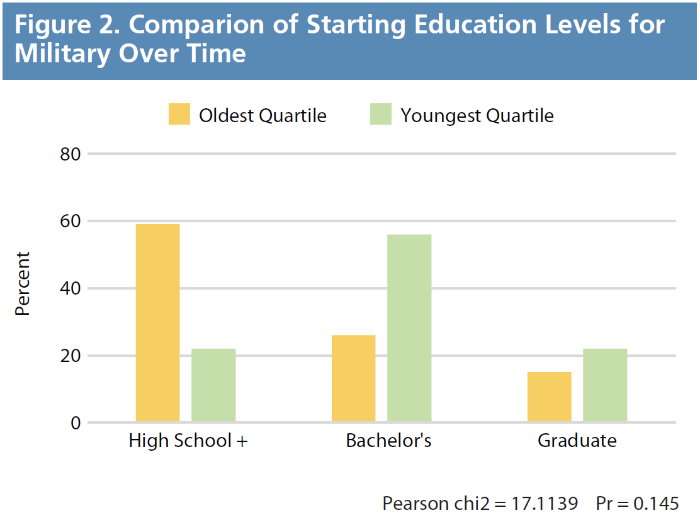

This divergence is particularly noteworthy for the military, as it shows a dramatic improvement in the education levels from earlier age cohorts. There were just 26 percent of bachelor’s degree holders among military recruits in the oldest age cohort. Consequently, over a several-decade period, the percentage of military recruits with bachelor’s degrees increased by 30 percentage points. Likewise, the percentage of those in the youngest cohort joining the military with a high school diploma (22 percent) is roughly a third of the 59-percent figure for the oldest age cohort (see Figure 2). By contrast, starting education levels for the police have not shown such improvement. Rather, the percentage of those starting service with a bachelor’s degree remained consistent at 32–35 percent across the cohorts.

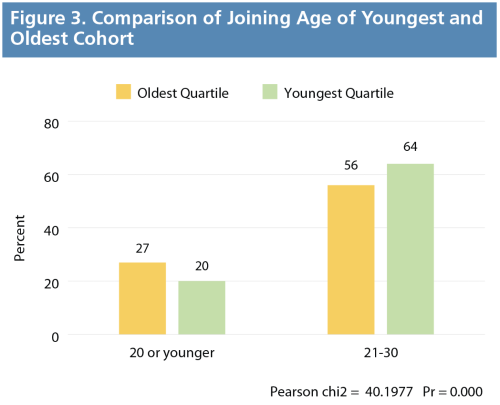

The emerging generation of African security sector professionals also tend to join the security services at an older age. While nearly 28 percent of the older cohorts of respondents had joined the service by the time they were 20 years old, that rate has dropped to 20 percent among the youngest cohort (see Figure 3). Inversely, 65 percent of the youngest cohort of security sector professionals joined their respective service during their twenties. This is an increase of 10 percentage points from the oldest cohort.

Those in the gendarmerie and police have tended to join at an older age than the military. Approximately 78 percent of the gendarmerie and 53 percent of police joined while in the 21–30 age range. This compares to 35 percent of those in the military.

Motivations

Motivation can be defined as an individual‘s degree of willingness to exert and maintain an effort toward organizational goals. Motivation is closely linked to job satisfaction, which leads to higher retention rates over time. Motivation is influenced by a complex set of professional, social, and economic factors. These include strong career development, adequate compensation, and satisfactory working and living conditions. Having strong human resource mechanisms within a security institution can help to ensure that the right motivational factors are in place to keep service members satisfied.

Inversely, problems with career development, salary, and working conditions are reasons security sector professionals become unmotivated. Any of these issues or a combination of them can lead to dissatisfaction. Career development is generally defined as the possibility to specialize in a particular field or be promoted through the ranks. A lack of promotion opportunities can be seen as demotivational.

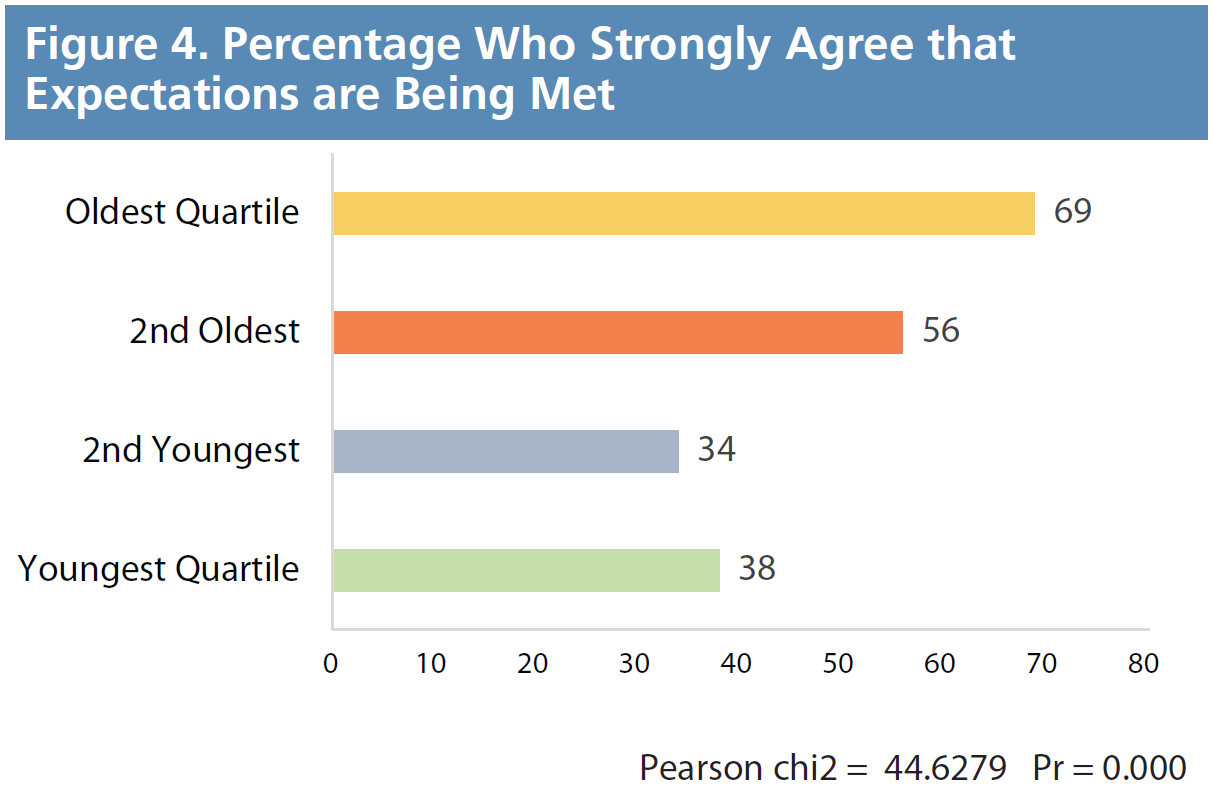

As indicated in the Survey Results section, the vast majority (92 percent) of service members surveyed indicated that they agreed or strongly agreed that their expectations for joining the service were being met. The strength of this sentiment varies by age, however. At a 69-percent rate, the oldest age cohort reported being most strongly in agreement that their expectations were being met (see Figure 4). This contrasts with a 38-percent level for the youngest age group.

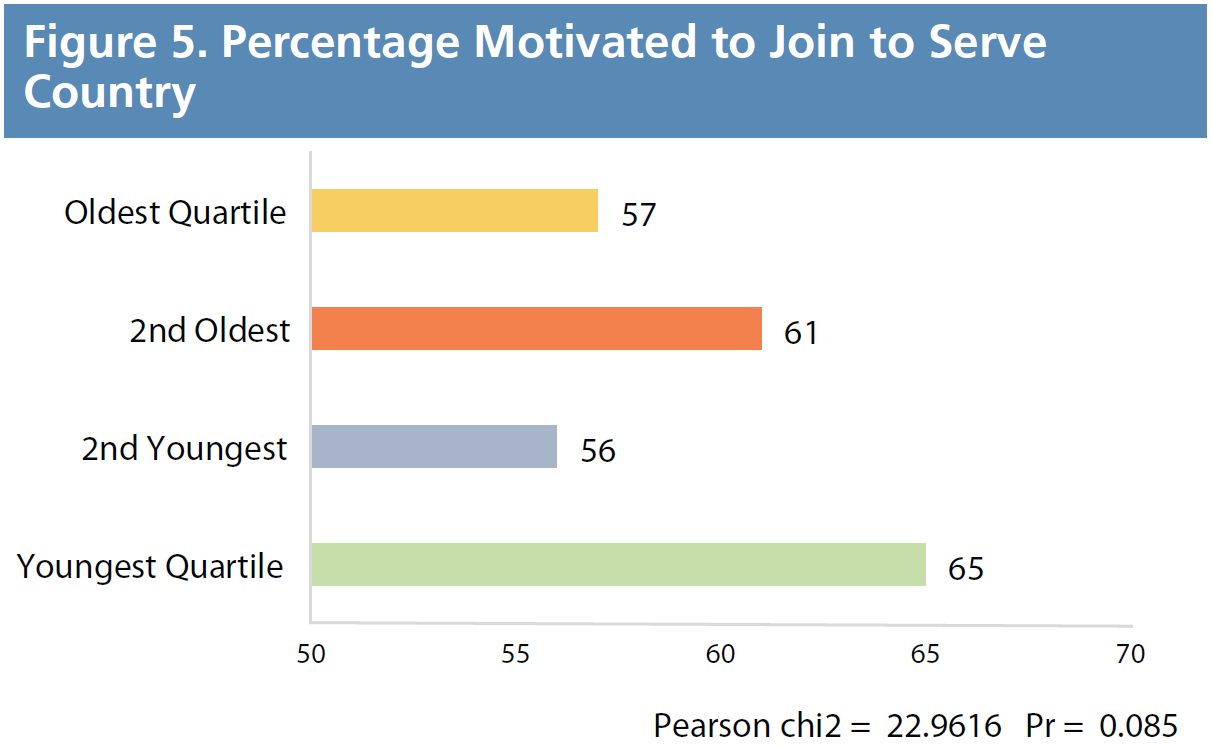

The strongest motivation for joining the service given by respondents was a desire to serve their country. Sixty-one percent of respondents cited this motivation (out of six choices). The preference for this motivation holds for all the services, with the motivations to serve the country being highest among the gendarmerie (70 percent), followed by the police and the military.

Notably, the motivation to serve one’s country was strongest among the youngest age cohort, of which a total of 65 percent of respondents indicated it as their primary motive for joining (see Figure 5). Such a result contrasts with the oldest quartile where 57 percent cited serving their country as the motivation for joining. This observation is noteworthy as it suggests a stronger sense of loyalty to the nation among younger age cohorts. By extension, this may reflect a greater willingness to respect civil authority and not threaten constitutional rule.

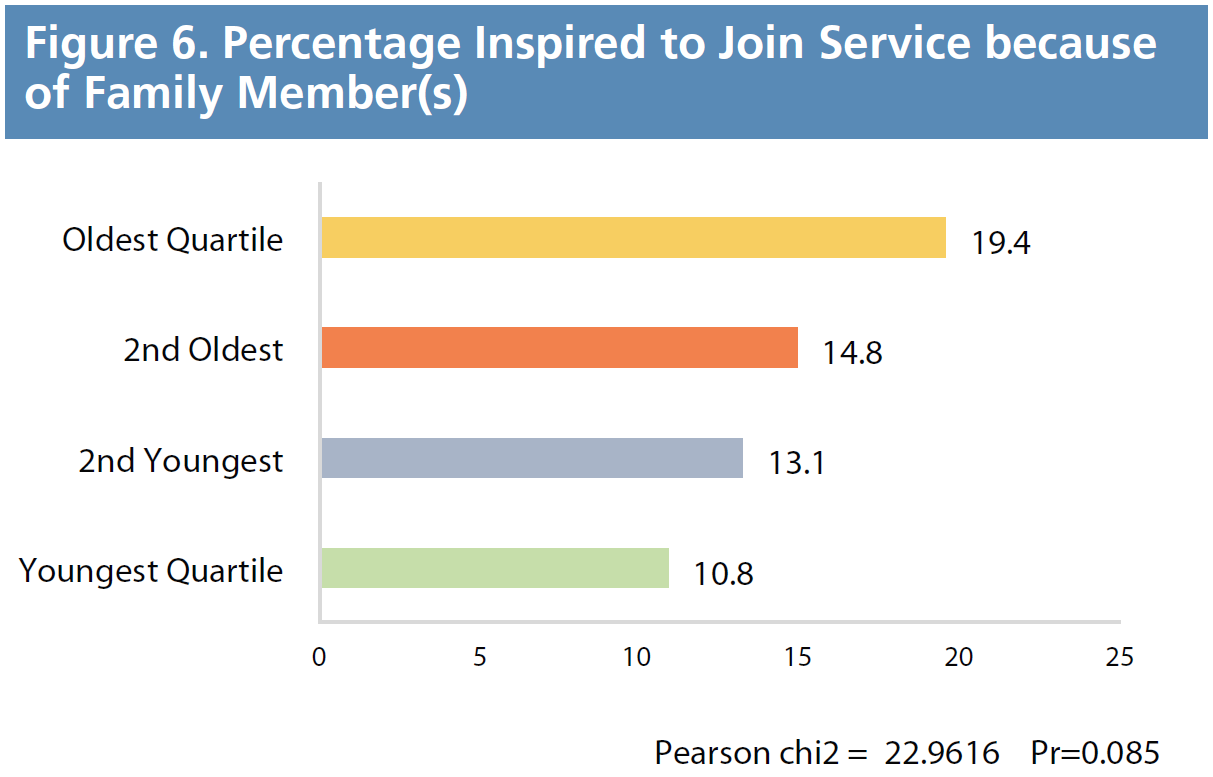

While older cohorts agreed that service to country was important, they also indicated that the issues of legacy, family, and friends played a strong motivational role. Among the six response options, 19 percent of survey respondents in the oldest age cohort indicated that family ties to the security services was a key motivation for them to join (see Figure 6). This influence was strongest within the military with 25 percent of respondents in the oldest cohort citing inspiration from examples of other family members.

By contrast, only 11 percent of the youngest cohort among all services (including the military) indicated that such legacy issues were a factor in their commitment to service. This trend may have significance for the historical development of African armies, in particular. These results may show that the close-knit familiar relations that characterized the military in the immediate independence period are giving way to a more diversified force that is more motivated to serve the public among the youngest age quartile.

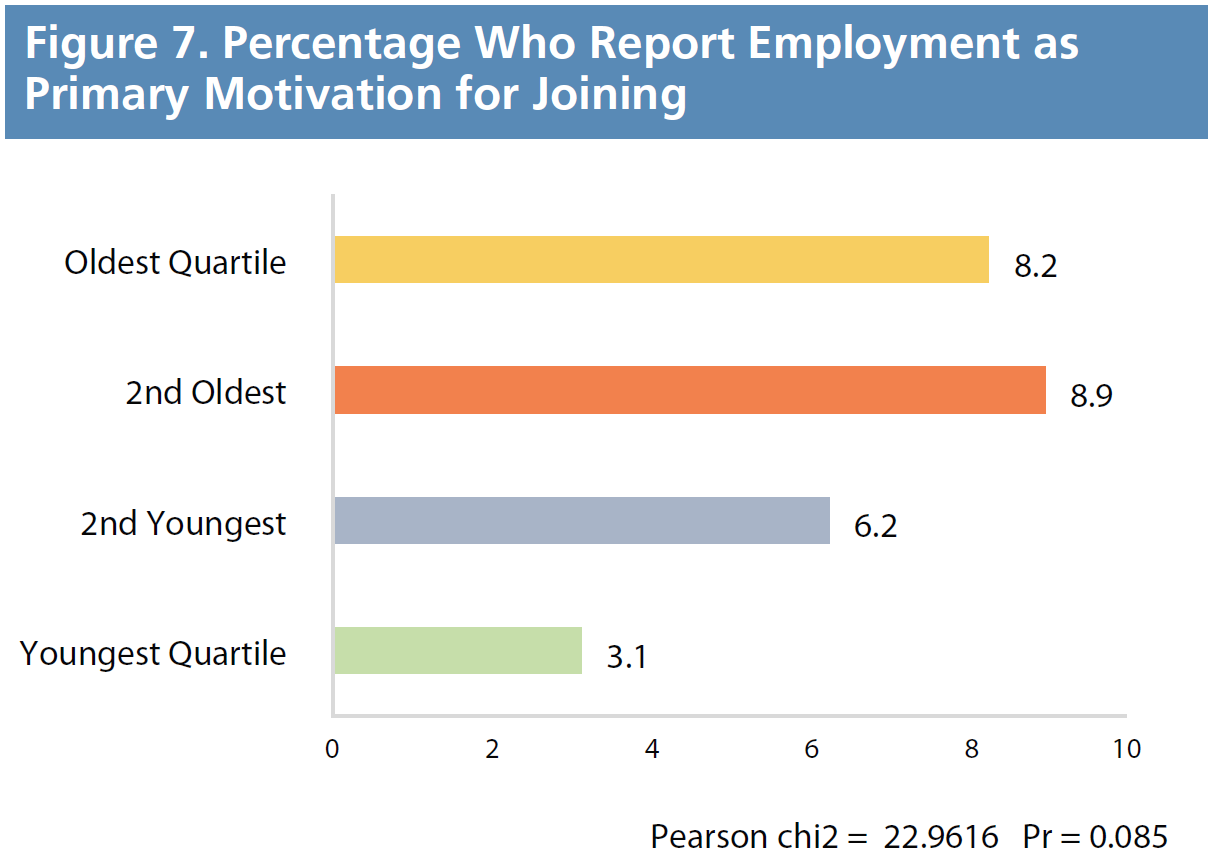

A common assumption is that African security sector professionals are primarily motivated by the need for employment. Indeed, several interview participants indicated that this was a key consideration for them and their peers. However, employment was cited by only 6.6 percent of the respondents as their primary reason for joining the service (see Figure 7). This rate ranged from a high of 8.2 percent for the oldest age cohort to just 3 percent for the youngest.

Coupled with the inverse pattern of responses for “service to the public” as a motivating factor (with the youngest cohort citing this as the strongest motivation relative to the oldest cohort) and the significantly higher starting education levels for young recruits, these results suggest that there has been a shift in reasons for joining the security sector over time. Young recruits today appear to have more skills and employment options, yet are willingly choosing to join the security sector as a means of service and a career.

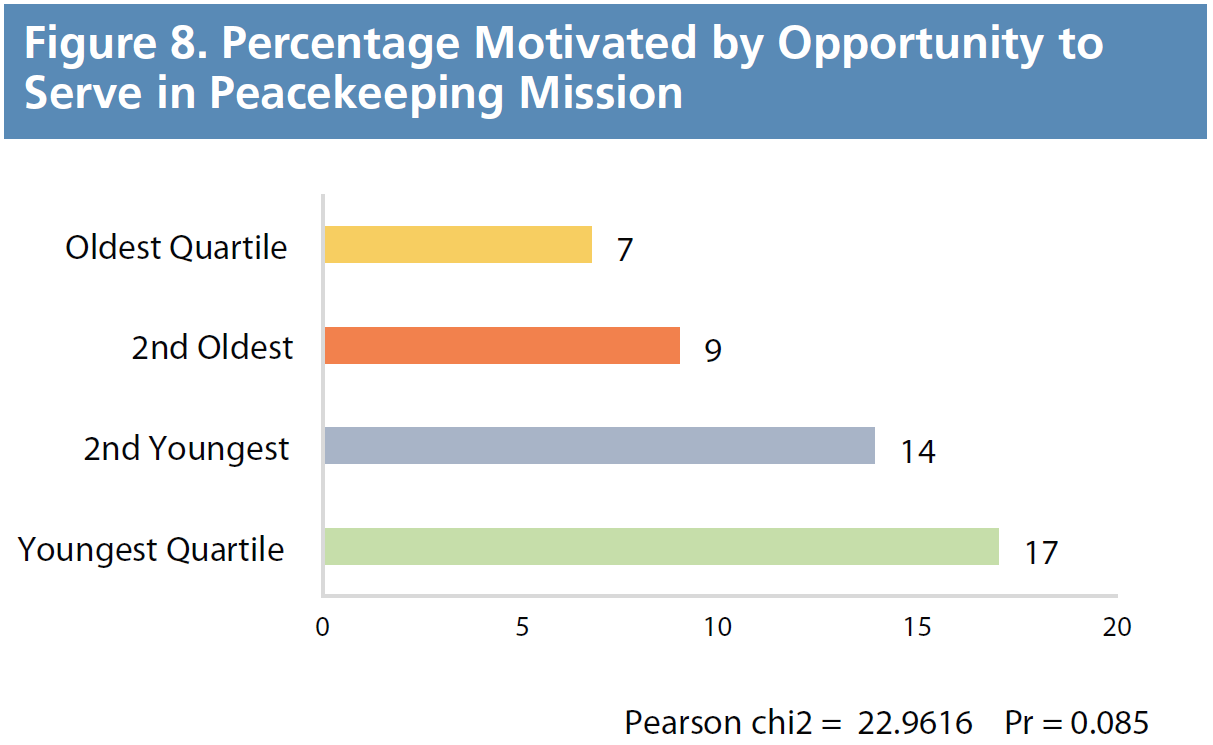

Another notable motivating factor that emerges from the survey is peacekeeping. With 15 international and regional peace missions deployed in Africa, peacekeeping represents an increasingly significant component of many African militaries’ mission. To that end, the youngest quartile seems to be increasingly motivated by the opportunity to serve in peacekeeping missions, with 17 percent being motivated by peacekeeping opportunities as compared to 7 percent for the oldest quartile (see Figure 8). This result suggests young service members see peacekeeping as an opportunity for gaining experience, professional advancement, and exposure to other countries.

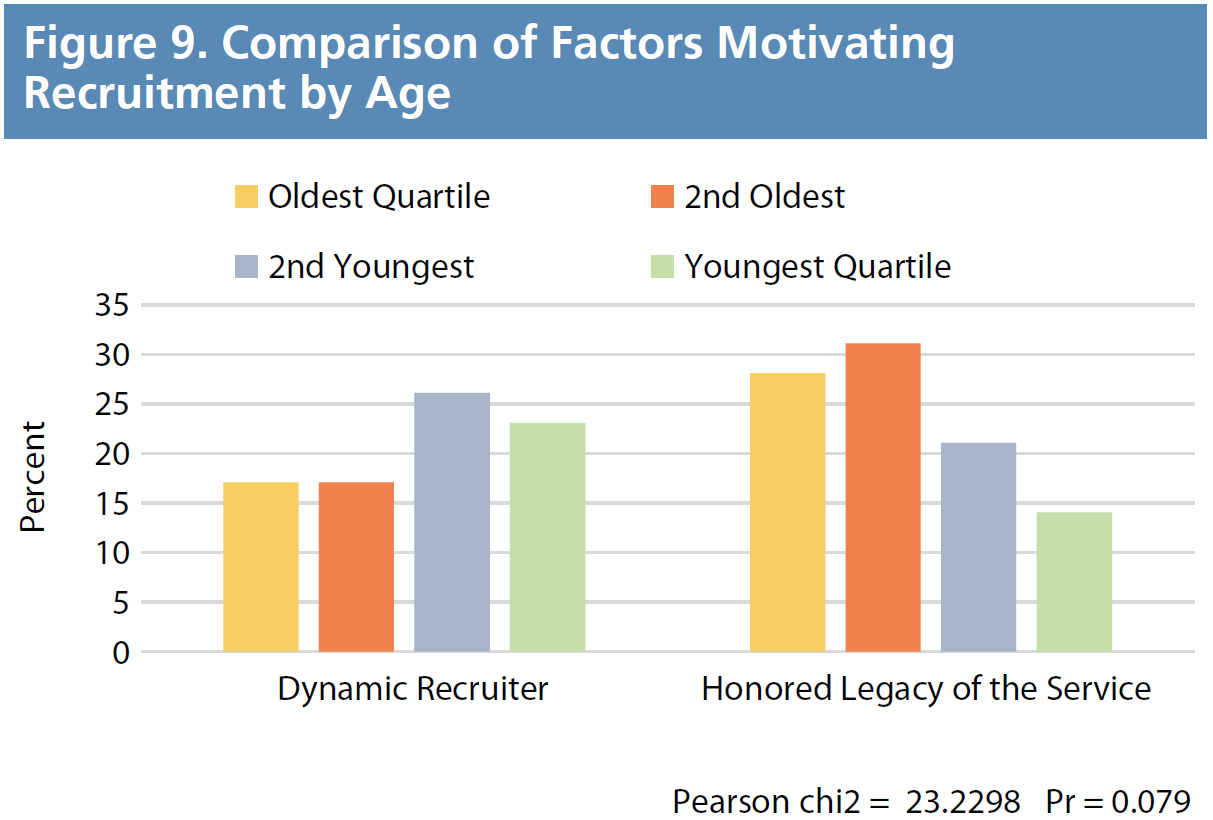

Differences between the age cohorts also emerge with regard to factors influencing recruitment (see Figure 9). Younger generations are more influenced by dynamic recruiters than older cohorts. Specifically, 25 percent of the youngest two quartiles indicated they were compelled by dynamic recruiters. This compares to 17 percent for the oldest two quartiles. Conversely, the younger cohorts were significantly less motivated by the legacy of service (14 percent) than were the older cohorts (28 percent). Notably, the legacy of service remains significantly more compelling for the military (34 percent) relative to the police and gendarmerie (18 percent, on average). Nonetheless, even within the military there is a significant decline in the importance placed on the legacy of service by the youngest cohort (12 percent). The finding of a decline in regard for the legacy of service among younger generations has potential long-term institutional implications for all of the security services.

Values and Identity Formation

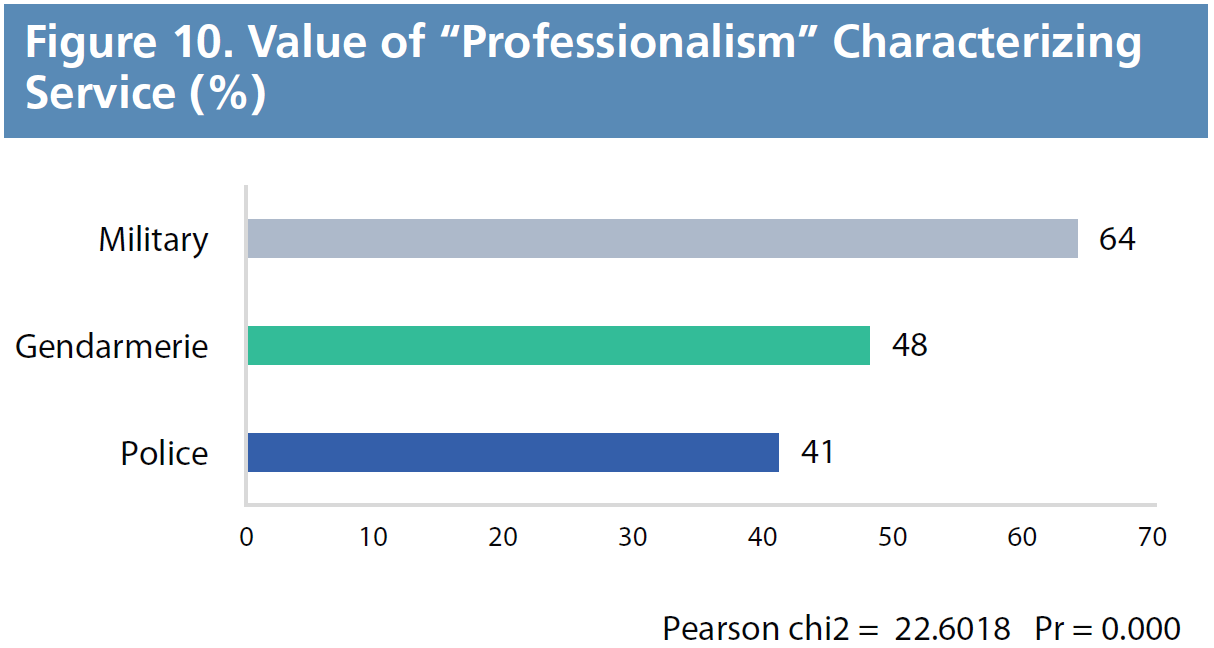

The survey results reveal a strong affinity among military respondents with their institution’s positive values. Specifically, respondents from the military reported at rates of 55–75 percent that the values of duty, responsibility, honesty, respect for citizens, and professionalism described their institutions. Notably, these values were only validated by the military respondents. For example, Figure 10 summarizes the disparity of responses from the respective services for one of these values, professionalism. It shows that 64 percent of military respondents felt that this value characterized their service. By contrast, only a minority of respondents (typically around 38–44 percent) from the gendarmerie or police indicated these values applied to their services.

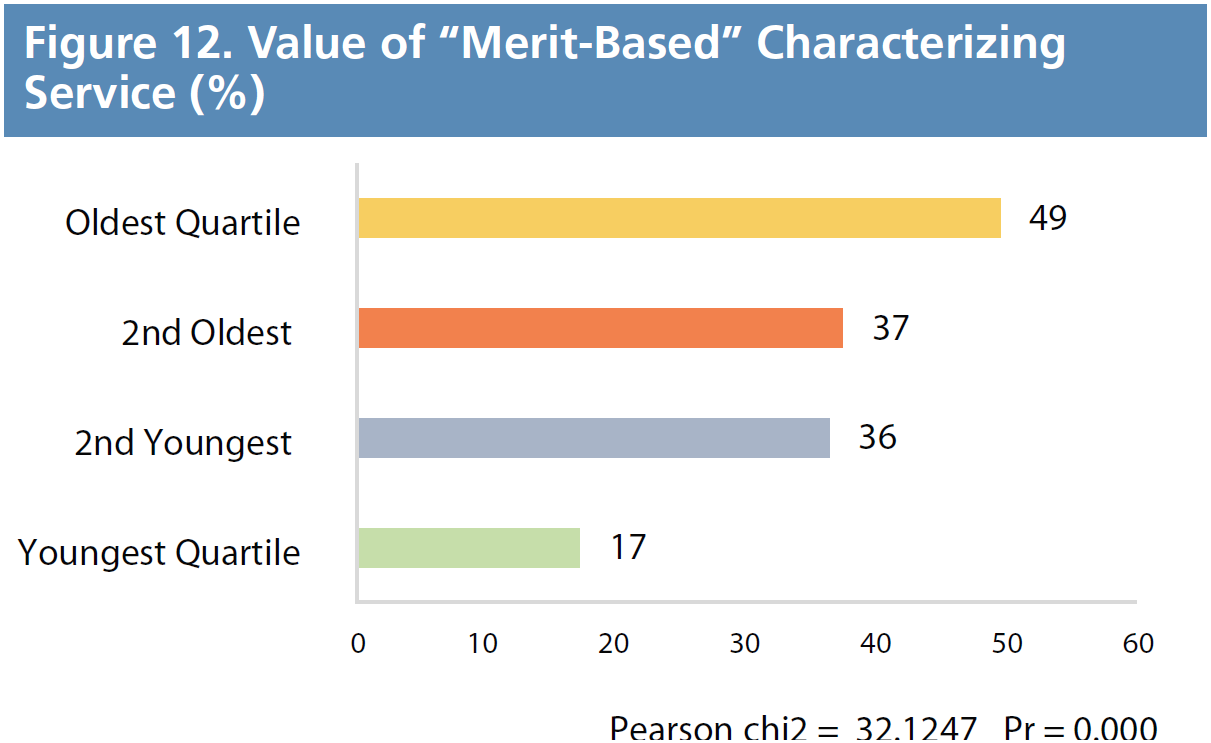

An important deviation within this value identification assessment was that values of “merit-based” and “service” do not seem to resonate strongly across any of the services. Just 48 percent of military respondents and only 25 and 38 percent of police and gendarmerie, respectively, indicated that merit-based values characterized their branches. Similarly, a minority of respondents for the police and gendarmerie (38 percent each) and military (47 percent) ascribed the value of “service to the public” as embodied in their institutions.

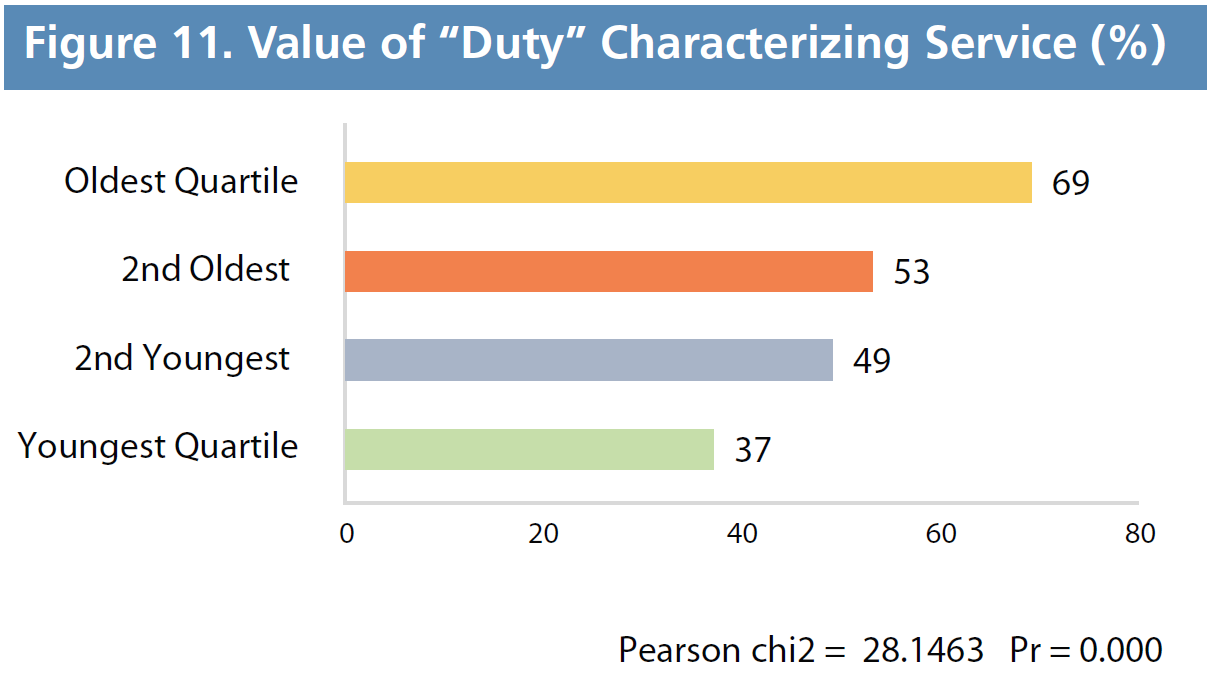

Interestingly, there is a strong age component to the value identification responses (see Figure 11). Specifically, the strongest associations across all of the values come from the older age quartiles (typically in the range of 55–70 percent). However, identification with such institutional values declines steadily for younger cohorts. For example, just 37 percent of the youngest cohort responded that the value of “duty” was representative of their service in Figure 11. This compares with 69 percent for the oldest cohort.

For the two values (“service to the public” and “merit-based”) that registered the least support, the youngest cohort scored lowest. Just 17 percent of respondents in the youngest age group indicated that the value of “merit-based” embodied their services (see Figure 12). In other words, by a 3:1 ratio, the youngest cohort rejected the characterization of “merit-based” and “service to the public” (not shown) for their organizations.

(Click to enlarge)

This pattern of declining adherence to institutional values by age—a pattern that held across all values surveyed—is potentially highly relevant in terms of the levels of embeddedness of these values. It may also suggest an erosion of support for such positive institutional assessments. If service personnel do not believe their institutions uphold positive values, this portends poorly for morale. Alternatively, it may reflect a more nuanced and constructively critical determination of the state of these institutions relative to their societies. This is particularly noteworthy since the youngest cohort had indicated that “service to the public” was their strongest motivation for joining the security sector. This suggests a significant disconnect between expectations and perceptions by this youngest cohort.

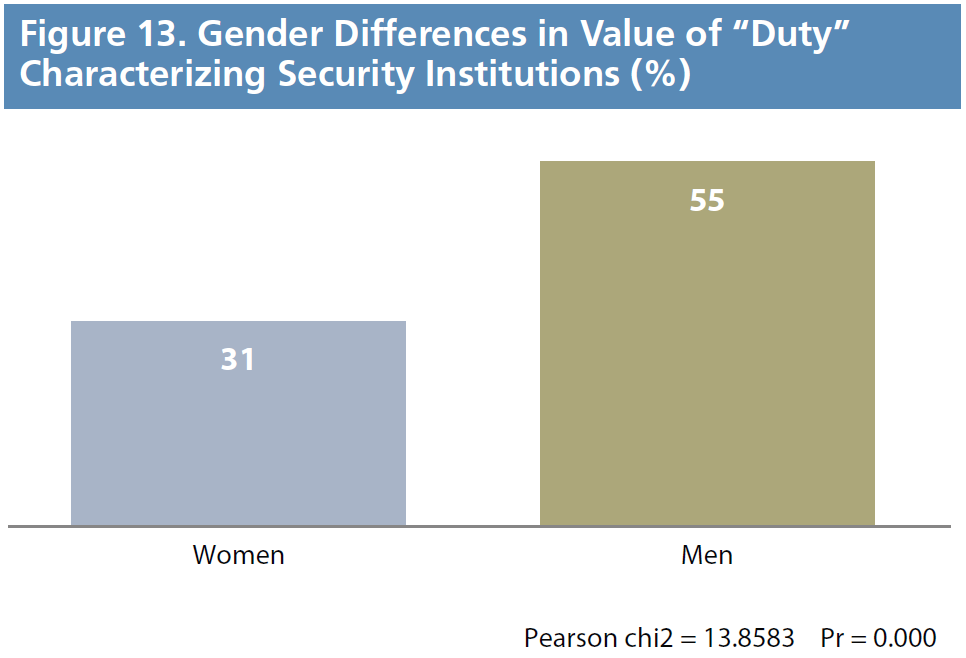

A marked divergence in identification of institutional values also emerges along gender lines. Specifically, women respondents, at a rate of 55–75 percent, do not identify with any of the values as representative of their respective institutions. For example, as Figure 13 shows, only 31 percent of female respondents indicate that “duty” is a common value that described their branch of service. This contrasts with a 51-percent response rate for men. Women in the military, however, generally identify more positively with all of the institutional values surveyed relative to women in the other services. While positive response rates among females in the military are usually not as strong as male military respondents, they are, typically, above 50 percent.

These gender differences are noteworthy for their consistency across all of the values. As with the younger cohort of respondents, these divergent perceptions from women may reflect a healthy reluctance to endorse values they feel are not well embodied in their institutions. It may also reflect a greater sense that women and younger cohorts are disadvantaged under the current state of their institutions. They are, therefore, less willing to endorse the suggestion that these institutional values have been realized.

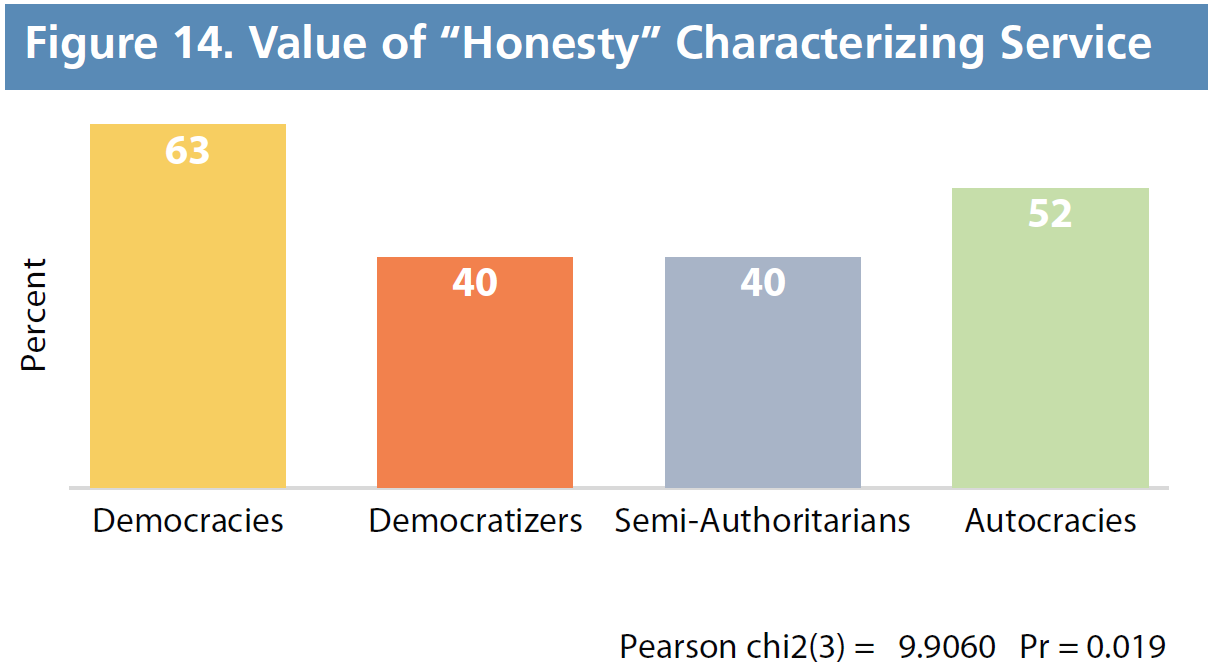

The survey also revealed some notable differences based on regime type. Specifically, respondents from democracies tended to indicate a stronger identification with all of the institutional values (e.g., duty, responsibility, honesty, respect for citizens, serving the public) than respondents from any of the other regime types. For instance, 63 percent of respondents from democracies identified the value of “honesty” as characterizing their service, though only 46 percent of the respondents from the other regime types combined felt this way (see Figure 14). The one notable exception was with regard to “merit-based.” Here, the responses from democracies (37 percent) were in the same range as the other regime types.

Interestingly, respondents from autocracies were the group that showed the next most robust identification with values, especially for values of professionalism, duty, responsibility, respect for citizens, and honesty. This suggests that strong institutional legacies can be created within such regimes (presumably the most stable).

Equally relevantly, respondents from mixed regimes (democratizers and semi-authoritarians) had a discernible paucity of positive responses to the identification with the values of professionalism, service to the public, and honesty. Only a minority of respondents indicated that these values characterized the ethos of their organizations. This has important policy relevance for defense institution strengthening efforts in transitioning societies. Deepening the shared values and identification of what a service stands for vis-à-vis citizens is an area requiring attention. This, in turn, may help sustain and advance democratization processes within these societies.

There were also divergences between regime types with regard to potential threats faced. For example, only 11 percent of respondents from democracies perceived risk of political crisis to be a serious concern (see Figure 15). This compared to 58 percent of respondents from democracies who classified risk of political crisis as low. The perceptions were reversed for respondents from autocracies. Among this group, 41 percent of respondents perceived risk of political crisis as a serious concern. Only 27 percent characterized this risk as low.

The survey responses also revealed that African security sector professionals, by and large, feel that there is a solid level of public support for their service. Overall, 88 percent of respondents indicated that there is a positive or highly positive level of support. This sentiment was significantly stronger within the military with 94 percent reporting favorable support, 47 percent of which was deemed highly positive. For the services more directly engaged with the public, the police and gendarmerie, the perceptions of highly positive support was significantly more modest, 22 and 33 percent, respectively. Among police, 17 percent responded that the public held negative perceptions of their service. Older age cohorts reported stronger levels of public support than the younger service members (see Figure 16). Specifically, 41 percent of the oldest two cohorts felt there was highly positive support compared to just 23 percent among the two youngest age cohorts.

International Training and Partners

One of the strongest findings from the survey was the high regard for international training. Some 97 percent of respondents viewed international training as a positive option. The value of international training as a formative experience was strongly validated in the qualitative interviews, where interviewees extolled such benefits as the:

- broadening of intellectual experiences and networks, including access to the latest knowledge and trends

- building of lasting relationships from their professional military education, including exposure to new ideas, values, critical thinking and evolving trends, while concurrently broadening contact with other cultures

- close exposure to senior leaders who demonstrate strong moral leadership and vision, which was identified as highly influential in the formative experiences of younger officers

- deeper understanding of members of the officer corps from different backgrounds

- creation of shared standards, vision, norms, and values with international partners

- building regional and global perspectives on security challenges and alternative means for addressing these challenges

- exposure to new technologies

Most respondents saw the importance of international training as a value in and of itself more so than the participation of any specific international partner. In fact, 83 percent of respondents indicated that there was value in having a diversity of international training partners rather than just one or two. For respondents expressing an interest in preferred training partners, the United States (27 percent), the African Union (21 percent), the United Nations (15 percent), and the European Union (9 percent) were seen as most favored. The strong showing of multilateral institutions is noteworthy in this regard.

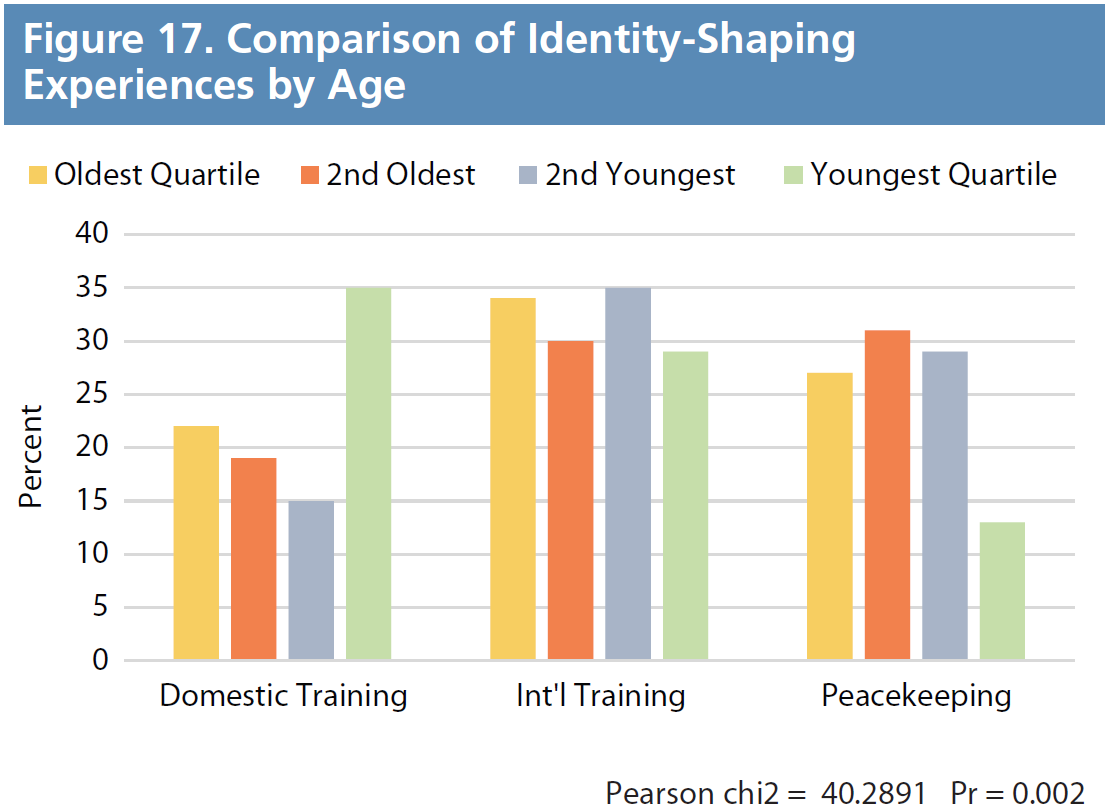

While there was a general consensus on the importance of international training, variations in age and service did emerge. International training was indicated as decidedly more formative than domestic training among the three oldest age cohorts (see Figure 17). Notably, the inverse was the case for the youngest age cohort, which stands out as an outlier. This cohort rated the influence of domestic training as the most influential formative experience. This was followed by international training and then peacekeeping. (Recall that the youngest cohort had indicated that the opportunity for peacekeeping deployments was a key motivation for them to join the service.) This divergence among the youngest age cohort may simply reflect their limited opportunities, thus far, for peacekeeping deployments or international training experiences.

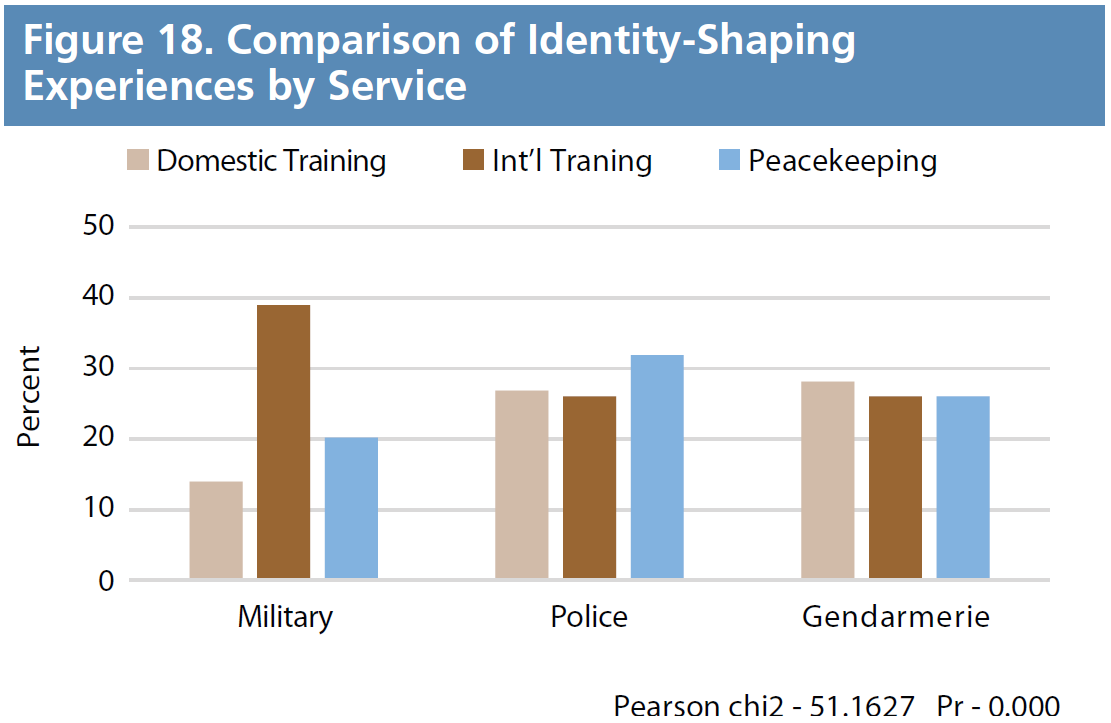

In terms of services, military respondents stood out in citing international training as the single most important formative experience in shaping the identity of their service. By a 2:1 margin, international training experiences were seen as more influential than domestic training (see Figure 18). This pattern does not hold for the police and gendarmerie, which cited training inside the country as of equal value to international training.

Somewhat counterintuitively, given their domestic orientation, peacekeeping was reported to be the single greatest influence for the police. This may highlight the growing role of police deployments in African peace operations, particularly in West Africa. For the military respondents, peacekeeping deployments ranked after international trainings as the most influential in shaping the identity of a member‘s service, followed by domestic training. The growing prominence of peacekeeping experiences in the identity formation of African security services is a noteworthy trend to track as they increasingly take on these roles.

Interviews underscored the premium placed on the ability to speak English in creating opportunities for international training and advancing the careers of African security personnel. The unintended downside to this is the large number of outstanding young leaders whose careers are limited because they do not have opportunities to develop their English language skills.

Regional Variations

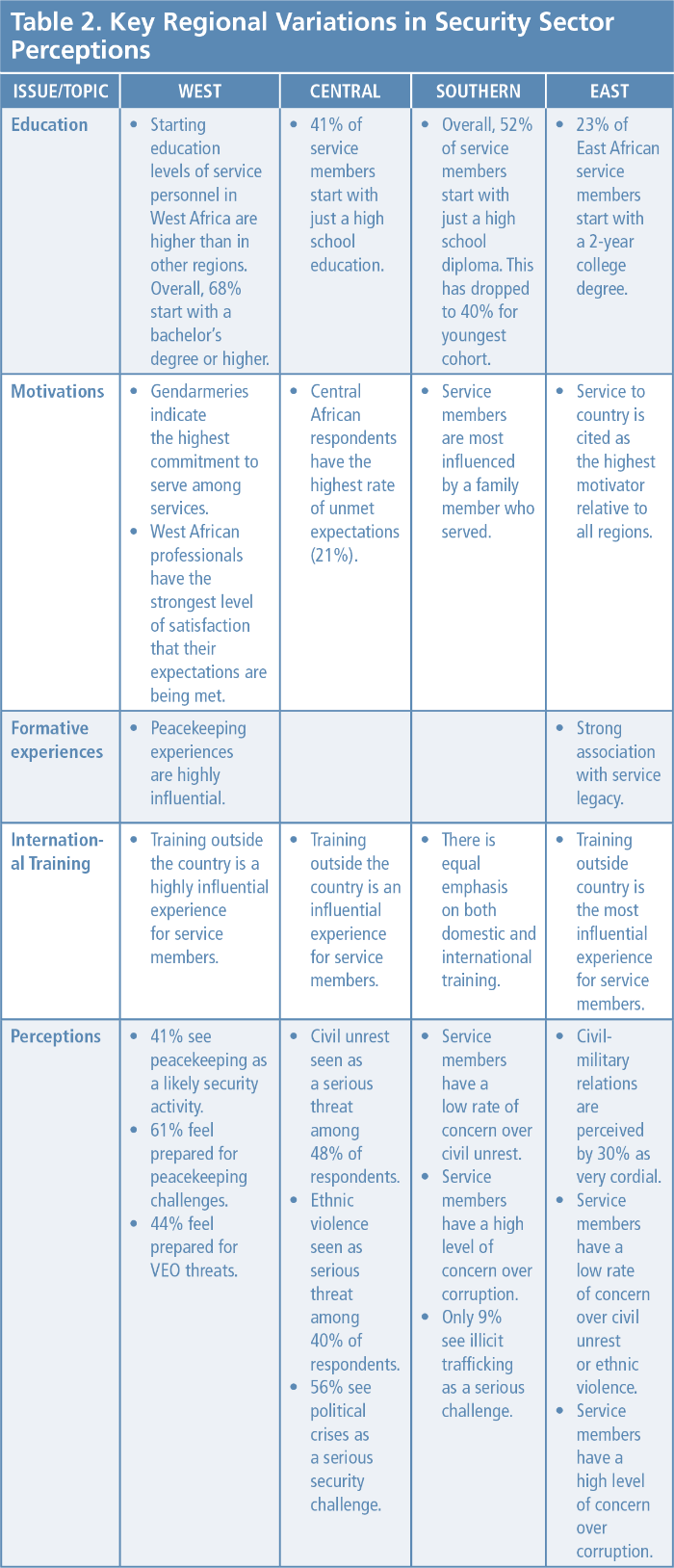

There are strong regional variations that emerge in attitudes and perceptions among African security sectors owing to their historical roots, traditions, and threats. Table 2 captures a number of the most noteworthy regional variations. These include:

Education. Education levels for recruits in West Africa are notably higher than in other regions on the continent. Some 68 percent of young security sector professionals surveyed in West Africa had at least a bachelor’s degree when they started their service. Only 15 percent began service with a high school diploma as their highest level of educational attainment. In contrast, 40 percent of new service members in Central Africa and East Africa started with a high school diploma as their highest educational degree.

Peacekeeping. West Africans were also the most influenced by peacekeeping experiences as a factor in service identity. Twenty-nine percent of West Africans saw peacekeeping as the most influential experience, compared to an average of just 16 percent for the other regions.

Corruption. Southern and East African respondents stand out for their concern over corruption. Ninety-five percent felt it a “medium” or “high” security problem. This response does not indicate that there are higher levels of corruption in these regions. Rather, it indicates that service members are particularly troubled by and perceive the security implications from high levels of corruption. While also high, concerns over corruption are relatively lower in Central and West Africa, at 75 and 85 percent, respectively. Taken as a whole, the results underscore the widespread recognition of the threat to security posed by corruption.

Violent Extremist Organizations. East and Central African service members see violent extremist organizations (VEOs) as a concern, with 73 percent of respondents reporting this as a “medium” or “high” threat. In contrast, Southern Africa stands out as having a very low perception of VEOs as a threat with just 2 percent identifying this a “high” threat and 16 percent viewed this as a moderate concern. Perceptions in West Africa fall in between with 60 percent seeing VEOs as a moderate or high threat.

Illicit Trafficking. Central African respondents indicated the highest level of concern over illicit trafficking with nearly 80 percent rating this as a “high” or “medium” threat. Reflecting a modest degree of concern, 65 percent of service members in West and Southern Africa rated illicit trafficking as a “low” threat. East Africa was distinctive in that it was much less likely to see illicit trafficking as a “high” threat (9 percent), compared to a 29-percent rate for all respondents.

Public Support. East Africans have a particularly positive perception of public support, with 49 percent of respondents rating this as “very high,” compared to 32 percent over all. More generally, roughly 90 percent of service members from Central, East, and West Africa believed there were “high” to “very high” levels of public support for their services. Southern Africans, by contrast, reported the most cautious level of public support for their services, with 29 percent indicating negative perceptions and only 21 percent finding this support to be “very high.”

International Training. East Africans were the region attributing the highest importance to international training with 46 percent citing this as the most influential factor in shaping their service’s identity. (This is three times the level recorded for domestic training). Respondents from West and Central Africa also indicated a clear affirmation of the impact from international training on identity formation above and beyond domestic training. Support in Southern Africa was more modest with 33 percent of service members identifying international training as a key formative experience. This is roughly comparable to the value placed on domestic training.

Civil Unrest. Central African respondents expressed much more concern about civil unrest than those from other regions. Forty-eight percent reported civil unrest as a serious concern, double the rate found elsewhere on the continent. By contrast, 50 percent of East and Southern African service members considered civil unrest a “low” threat. Central African respondents were also more likely to see the risk of political crisis as a challenge. Fifty-six percent of service members from this region saw political crises as a “high” threat (compared to 24 percent overall). Central Africa, similarly, stands out for seeing ethnic violence as a “high” threat (40 percent). By contrast, only 7 percent of Southern Africans felt this way and 19 percent over all.

[1] All of the comparative results highlighted in this Analysis section are statistically significant in Pearson chi-squared tests of the categorical variables, typically at or above a 90 percent confidence interval. Specific significance results are reported with each figure.