Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Reversing the escalating violence of militant Islamist groups in the Sahel will require an enhanced security presence coupled with more sustained outreach to local communities.

Mali soldiers on patrol in Gao the day after a suicide attack. (Photo: AFP)

Highlights

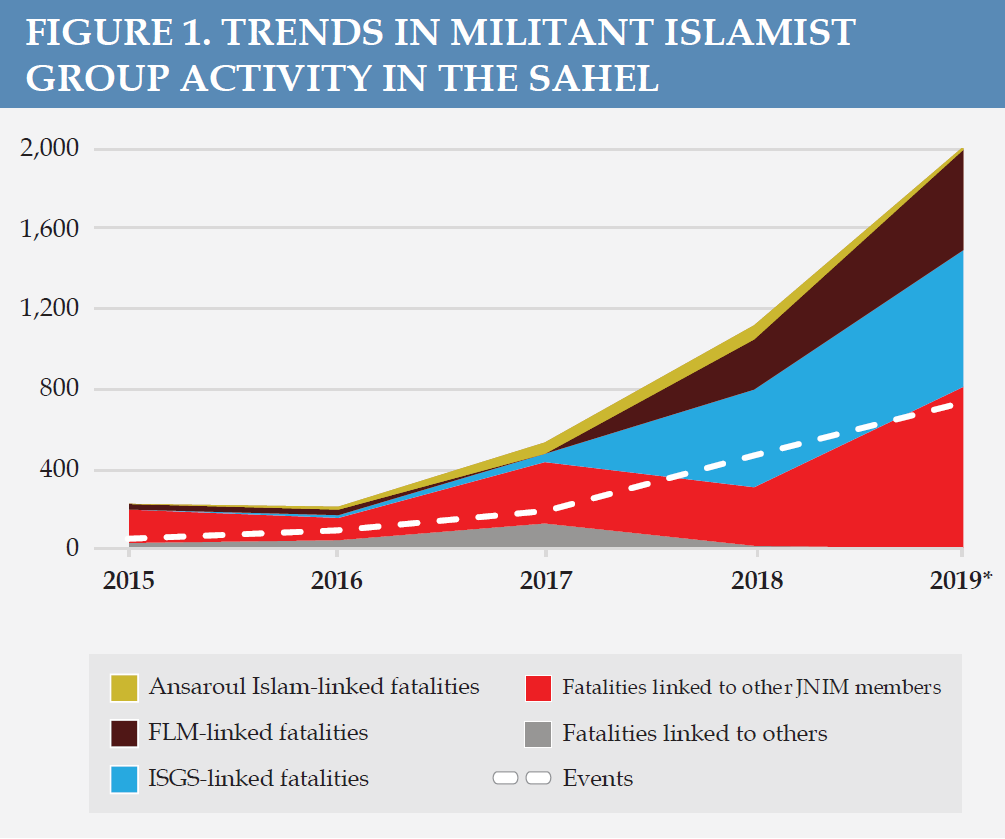

- Violent activity involving militant Islamist groups in the Sahel—primarily the Macina Liberation Front, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, and Ansaroul Islam—has doubled every year since 2015.

- Employing asymmetric tactics and close coordination, these militant groups have amplified local grievances and intercommunal differences as a means of mobilizing recruitment and fostering antigovernment sentiments in marginalized communities.

- Given the complex social dimensions of this violence, Sahelian governments should make more concerted efforts to bolster solidarity with affected communities while asserting a more robust and mobile security presence in contested regions.

The Sahel has experienced the most rapid increase in militant Islamist group activity of any region in Africa in recent years. Violent events involving extremist groups in the region have doubled every year since 2015. In 2019, there have been more than 700 such violent episodes (see Figure 1). Fatalities linked to these events have increased from 225 to 2,000 during the same period. This surge in violence has uprooted more than 900,000 people, including 500,000 in Burkina Faso in 2019 alone.

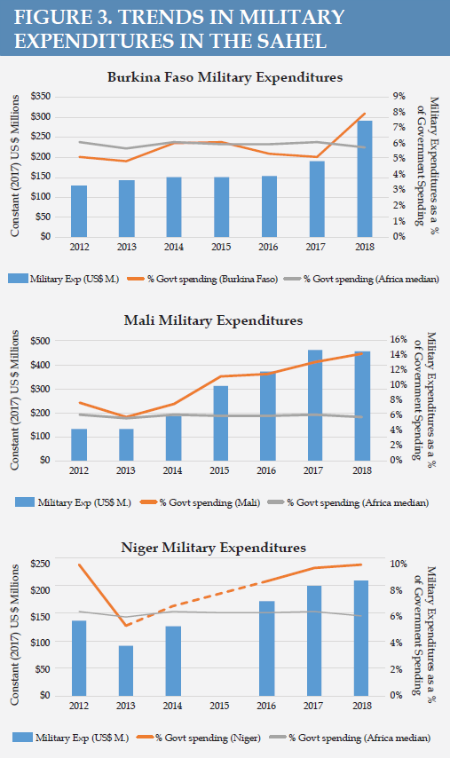

Three groups, the Macina Liberation Front (FLM),1 the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS),2 and Ansaroul Islam,3 are responsible for roughly two-thirds of the extremist violence in the central Sahel.4 Their attacks are largely concentrated in central Mali, northern and eastern Burkina Faso, and western Niger (see Figure 2). Multiple security and development responses have been deployed to address this crisis. While some progress has been realized, the continued escalation of extremist violence underscores that more needs to be done.

Lessons from Confronting FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam

FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam are autonomous organizations with distinguishable geographic areas, leadership, and modalities. Nonetheless, certain common features emerge from their operations.

Exploiting Grievances for Radicalization

Each group, particularly FLM and Ansaroul Islam, has skillfully incorporated local grievances to create recruitment narratives centered on perceived marginalization. Frequently, these efforts have targeted young Fulani herders by stoking their feelings of injustice and resentment toward the government. While lacking deep local support, the militant groups have used this grievance narrative to radicalize individuals.

Both FLM and Ansaroul Islam benefited from their leaders’ charisma, ideology, and personal engagement to attract followers. FLM founder Amadou Koufa was radicalized through travels and foreign contacts who promoted an ultra-conservative vision of Islam. He, in turn, played a direct role in the radicalization of Ibrahim Malam Dicko who would go on to found Ansaroul Islam. Both Koufa and Dicko used their religious credentials as Fulani preachers to promulgate their views. All three groups have used traditional media such as radio broadcasts in conjunction with social media such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Facebook to spread their messages, stoke tensions with the government, and drive recruitment.

These groups have also used grievances to foment discord between communities, inciting violence. ISGS has exploited anger over cattle theft to exacerbate tensions between Tuareg nomads, seen as cattle rustlers, and the Fulani herders along the Niger-Mali border.5 Growing animosity between the two groups has increased insecurity in these areas. FLM, likewise, has tapped deep-seated local grievances to exploit social cleavages between Fulani and other local groups like the Bambara and Dogon. These recriminations have degenerated into ethnic clashes in central Mali.

Note: Data points represent violent events involving the designated groups in 2019.

Data source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)

Ibrahim Dicko pursued a similar strategy by criticizing religious and traditional hierarchies that organized politics and society in Burkina Faso’s Soum Province. Dicko argued that social order in Soum disproportionately benefited traditional chiefs and religious leaders at the expense of the general population. When security forces searching for militant Islamists from Mali employed heavy-handed tactics in Soum, Dicko weaved the events into a narrative of grievance directed at both the central government and the presumed complicity of traditional leaders to launch Ansaroul Islam’s violent campaign.

While these groups profit from spreading insecurity, they have so far failed to generate significant support among local communities. Even so, their tactics complicate the security challenge facing the region’s governments.

Undermining the Government

As part of their effort to contest governmental authority in the outlying areas where they operate, FLM, Ansaroul Islam, and ISGS have targeted security forces, teachers, civil servants, and community members who are seen as collaborating with government representatives. The void created by diminished government presence gives the militant groups more leverage to assert influence in the affected communities. Over time, a growing share of these groups’ activities have involved violent attacks on civilians. Ansaroul Islam has stood out in this regard, with 55 percent of the violent events attributed to the group targeting civilians.

Intimidated communities have thus grown hesitant to collaborate with security forces. At times, this has fostered suspicion by security forces, particularly in Mali and Burkina Faso, leading to collective reprisals and human rights abuses. This has further deteriorated levels of trust between communities and security forces.

FLM and Ansaroul Islam have actively sought to tie this cycle back into their radicalization narratives, highlighting the governments’ abuses and disinterest in local communities. In contrast, ISGS does not appear to have developed a sustained or cohesive ideologically driven narrative. Rather than winning people over, the group has focused instead on stretching the battlefield and exploiting country boundaries by employing highly mobile tactics to strike targets in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

High Degrees of Adaptation and Coordination

Another commonality of the three groups relates to their adaptability and coordination. The emergence of Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM) in 2017, a coalition of militant Islamist groups in the Sahel region, reflects a complex organizational structure that serves multiple purposes. While not an operational entity itself, JNIM facilitates communications and coordination among the affiliated groups, mitigating infighting. This is evidenced by the geographic concentration of activity by its member groups (see Figure 2). Like other umbrella associations, JNIM also shields its individual members from unwanted attention. For example, while FLM is the leading militant actor in central Mali, its strategic alliance through JNIM obscures the extent of FLM’s activities and allows it to maintain a relatively low international profile avoiding greater foreign attention.

While not officially part of the coalition, ISGS maintains close ties with JNIM members, facilitating the coordination of their respective activities. The ability and willingness of ISGS to coordinate with JNIM enables them to deconflict their activities while expanding the areas in which the militants operate. The coordination also demonstrates that despite formally splitting from the al Qaeda network in 2015, ISGS continues to operate like an al Qaeda affiliate even though it retains a nominal alliance with ISIS.

Ansaroul Islam underwent a leadership transition following the death of Dicko in 2017 that resulted in a surge of claimed attacks during 2018. The number of violent events attributed to Ansaroul Islam has subsequently diminished dramatically. As Ansaroul Islam’s reported activities have declined, however, attacks linked to JNIM have increased in northern Burkina Faso, suggesting that many Ansaroul Islam fighters may have joined the ranks of the coalition or simply turned to criminality. Thus, while the degradation of Ansaroul Islam’s capabilities points to the effects of sustained military pressure, the adaptability of militant Islamist groups in the region continues to thwart efforts to defeat them.

Promising Initiatives Underway in the Region

Despite the many challenges faced, security forces, government officials, NGOs, and local communities have undertaken a number of promising initiatives to combat the threat posed by FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam.

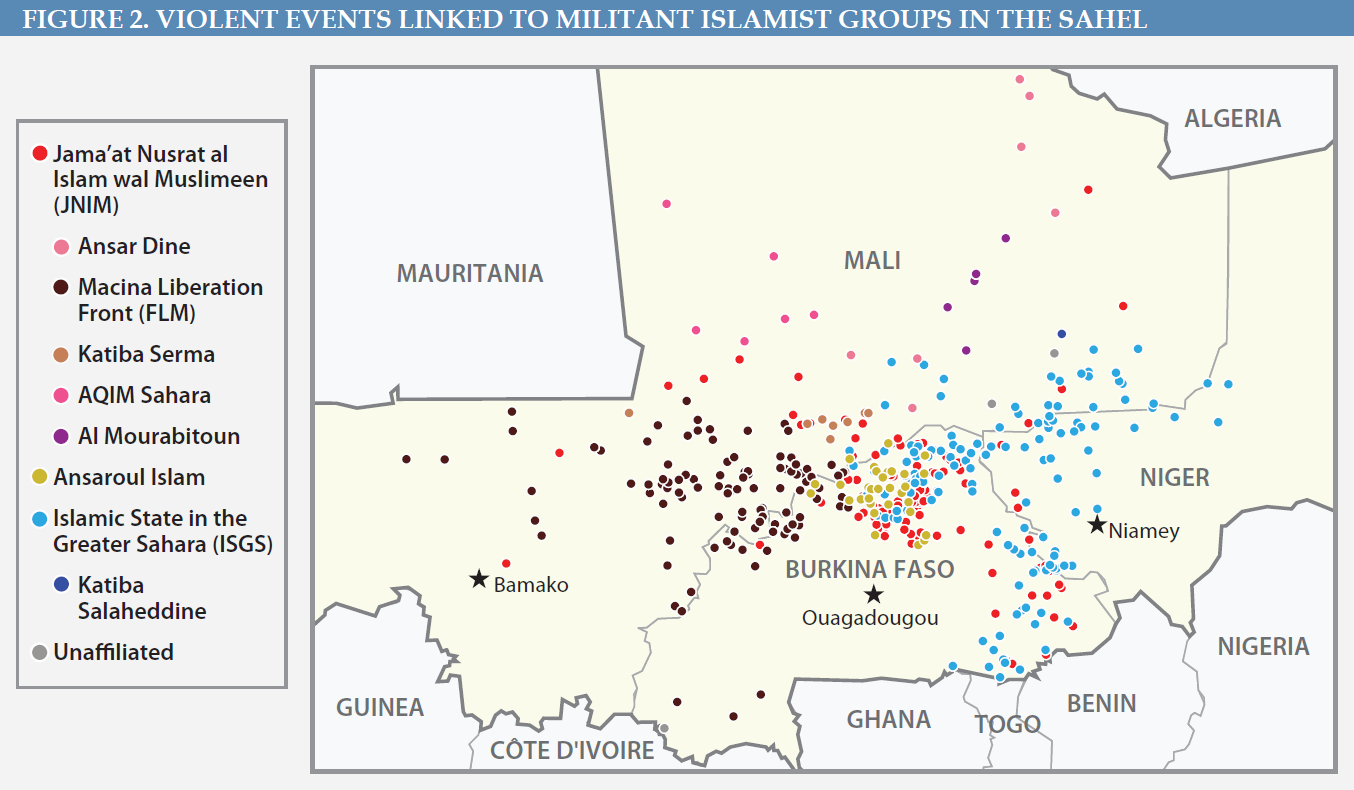

Security Responses

The governments of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have mobilized their security structures in an effort to respond to the rise in militant Islamist group violence. The budgets dedicated to the armed forces in the three affected countries have doubled since 2013 – from 5.4 percent of government spending, on average, to 10.6 percent (see Figure 3). This equates to an increase of nearly $600 million in military expenditures for these three countries.

The increase in security expenditures has been coupled with bolstered troop levels. Burkina Faso’s Minister of Defense announced a 50-percent increase in the number of annual recruits in August 2019. As part of an overhaul of its security sector, the Malian armed forces and gendarmerie have sought to add 5,000 and 1,500 new recruits (increases of around 30 percent and 18 percent), respectively. Nigerien troop levels have remained at around 10,000 soldiers in recent years, but increases in military spending have augmented troop salaries and equipment procurements.

In 2017, the Malian armed forces launched Operation Dambé deploying 4,000 soldiers to 8 zones covering northern and central Mali in an effort to counter the activities of violent extremist groups. The mission, updated in 2019, is to establish a population-centric posture in Mali and along the border with Burkina Faso and Niger. These efforts are complemented by mobile units deployed to disrupt militant Islamist group activities through increased patrols. While threats posed by FLM in central Mali continue, the increased presence of security forces has undoubtedly curbed the extremist group’s influence in key population centers in the region.

The Burkinabe armed forces launched Operation Otapuanu in March 2019 to counter the jihadist insurgency in the eastern part of the country and Operation Ndofou in May 2019 for the Nord, Centre-Nord, and Sahel Regions. The Burkinabe government also declared a state of emergency in December 2018 covering 14 of the country’s 45 provinces. Operation Otapuanu has enjoyed some success by limiting ISGS’s ability to traverse the territory easily. On the other hand, Operation Ndofou has struggled to reinstate security in the north where militants are familiar with the environment and easily cross the border into Mali taking advantage of the terrain.

In Niger, the military has led several joint special forces operations with the French-led Operation Barkhane targeting the leaders of militant Islamist groups. Niger has repeatedly placed the 10 departments bordering Mali and Burkina Faso under a state of emergency. In April 2019, Niger provided air support and increased the troops committed to active military operations in the western regions of the country—Dongo, Saki 2, and the joint Dongo-Barkhane missions. Saki 2 targets armed bandits, Dongo provides increased protection for communities, and Dongo’s joint operations with Barkhane aim to dismantle violent extremist organizations by going after high value targets. (Similar joint operations with Barkhane are periodically conducted by Malian and Burkinabe armed forces.)

Significant regional security efforts have also aimed to improve the armed forces’ capacity with increased access to resources, training, and equipment.6 This takes place through the G5 Sahel Joint Force (aimed at enhancing cooperation in the shared border areas), the European Union training missions in Mali and Niger, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), and other capacity building programs. From 2015 to 2019, Operation Barkhane neutralized over 600 terrorists. Similarly, Barkhane’s ability to quickly deploy and reinforce regional forces enhances their counterterrorism capabilities.

While these deployments have demonstrated noteworthy progress, the threat posed by militant Islamist groups remains a serious concern. Furthermore, the groups have adapted their tactics by laying improvised explosive devices (IEDs) as well as ambushing security forces after monitoring their patrol routes.

Bolstering Social Cohesion

A parallel security challenge posed by FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam, is their threat to social cohesion. These groups have purposively tried to exploit social cleavages to foment instability. This has resulted in an increase in intercommunal violence. In Burkina Faso, this threatens the social solidarity that has historically provided stability between the diverse communities in the north. Efforts to promote peacebuilding and social cohesion, accordingly, are vital.

Some small but effective initiatives in Burkina Faso have aimed to mitigate these threats by bolstering social ties. In cooperation with local community leaders, the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) in 2015 initiated the Justice and Security Dialogue in Saaba, Kadiogo Province, to explore ways to improve the security environment. This dialogue included members of the Koglweogo (a self-defense militia of mostly Mossi men), women, community organizers, youth representatives, and local politicians. Through this dialogue the community engaged in an extended exchange with Burkinabe police and gendarmerie. The dialogue has contributed to a reduction in intercommunal tensions while rebuilding trust between security forces and community members.

“These [militant] groups have purposively tried to exploit social cleavages to foment instability.”

Other initiatives have sought to provide a platform for the concerns of vulnerable populations in the region. Two parastatal organizations, the Haute autorité pour la consolidation de la paix (HACP) in Niger and the Centre de suivi et d’analyses citoyens des politiques publiques (CDCAP) in Burkina Faso play important roles in engaging Sahelian youth and communities that are more susceptible to the messages of militant Islamist groups. In Niger’s Tillabéri Region, HACP organizes community dialogues to take stock of ongoing projects and address shortcomings. When such exchanges are organized routinely, they enable communities to express their concerns and ensure that they are accounted for in the drafting of public policy.7 Similarly, in Burkina Faso, the CDCAP created a civil society network, gathering contributions from the populations of outlying regions through community consulting groups (“cadres de concertation communaux”) to convey their views to Burkinabe authorities.8 Local representative bodies such as these present an invaluable opportunity to connect traditional authorities and young people.

The activities of HACP and CDCAP indicate that expanding community engagement can reduce perceived grievances and resentment toward the government. Similar activities may prove to be useful in central Mali as the government and local groups seek to restore security and amplify local representation. Doing so may help further cut the limited support for violent extremist organizations.

Actors who participate in government-linked initiatives, however, have very often become high value targets for militant groups. Each group, FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam, has targeted community leaders in assassinations and terrorized communities by killing those suspected of government collaboration. This was the case in a similar initiative in the Tillabéri Region of Niger, where ISGS targeted senior Tuareg leaders in an attempt to crush ongoing efforts to enhance intercommunal dialogue. For any community-based peacebuilding initiatives to be successful, therefore, community leaders need to be protected.

Extending the Reach of Government

A reality in the Sahel is the challenge for governments to maintain a presence across their expansive territories in a highly resource-constrained environment. Any governance and security strategy for Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, accordingly, will require forming networks with a variety of nonstate actors such as traditional leaders, community-based groups, and NGOs.9 An example of this is in the justice sector. In Burkina Faso, the Mouvement Burkinabè des droits de l’homme et des peuples (MBDHP) receives complaints, initiates legal actions, and accompanies clients with pro bono lawyers for those who have suffered from conflict. This important work helps to provide some legal recourse for communities affected by insecurity. Elsewhere in Africa, alternative dispute resolution mechanisms that support overstretched judiciary institutions have been seen to increase perceptions of justice and, consequently, increase stability.10

NGOs can also play a central role in training security forces to better observe human rights and address potential abuses. In Burkina Faso, local civil society organizations such as the Centre d’information et de formation en matière de droits humains en Afrique (CIFDHA) and the MBDHP provide trainings on human rights and cultural awareness to the police and gendarmerie as do international organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross. Currently, these trainings need to be scaled up and adapted for all security forces prior to their deployment in violence-affected zones.

The education sector presents another arena in which collaboration between government, NGOs, and local communities has shown results. In the central Sahel, most public schools lack funding and are often unable to enroll all children, especially those following a nomadic way of life. Consequently, children in pastoralist communities have historically attended Quranic schools. These students are disadvantaged because they have not been through a formal education system making them less employable and potentially more prone to radicalization.11 Ouagadougou-based NGO, l’Association IQRA, works in collaboration with foreign donors and religious leaders to create and disseminate a common curriculum for Quranic schools.

Recommendations

Despite some significant steps to counter FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam, much more remains to be done. Given the multifaceted strategies deployed by these groups, a diverse set of responses will be necessary to defeat them.

Sustain a security presence in marginalized areas. Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso have taken some encouraging steps to counter FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam through military operations Dambé, Dongo, Otapuanu, Ndofou, and Saki 2. These operations need continued support if they are to degrade militant Islamist group capabilities. Supplementing these operations with quick reaction forces by enhancing the mobility of select units to reinforce positions and target militant Islamist groups as intelligence comes in will be crucial to defeating them. The 2019 revised concept of operations in Mali reflects the need to shift strategies towards highly mobile offensives and quick reaction reinforcements to combat these groups’ asymmetric tactics.

This is particularly the case in the fight against ISGS which uses its own rapid mobility as a tactical advantage over the armed forces of Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali. Increasing the mobility of select units will also bolster the defensive posture of troops stationed at strategic bases and aid in the disruption of the JNIM coalition’s abilities to coordinate among one another.

“[E]nhancing the mobility of select units ….will be critical.”

For troops already deployed to protect communities in the zones covered by these operations, greater effort is needed to integrate community leaders and representatives in security planning. Establishing liaison teams between communities and battalions could create a point of contact between the different parties helping to ensure that lines of communication are clear and open. Improving coordination in this manner would bolster the ability of troops to respond to communities’ security needs.

A key element of sustaining an expanded security presence in marginalized areas is providing better protection for community leaders and members who engage with government representatives and security forces so they do not fear the retaliation of violent extremists. Consequently, security forces need to assure communities that they will be protected. This is particularly important in countering FLM, which is embedded in many communities of central Mali.

Improve security in the border regions. The vast and poorly patrolled border regions of Sahelian countries provide refuge to militant Islamists. They also provide exploitable revenue streams for these groups by connecting them to weapons, drugs, and human trafficking networks as well as offering up an expansive territory upon which to establish protection schemes over communities.12 ISGS, in particular, has benefited tactically from this situation and increased its access to equipment, funding, and communications while strengthening ties with other extremist organizations active in the Sahel.

The G5 Sahel Joint Force is uniquely placed to help in the border regions as well as provide a platform to coordinate and reinforce regional security collaboration. The G5 Sahel and the national armed forces of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso should consider developing rapid deployment forces or other nontraditional units capable of responding to threats that emanate from expansive land areas and across country borders. Governments will need to consider restructuring their armed forces to better meet the challenges presented by asymmetric warfare and highly mobile adversaries.13 This will require improved cross-border coordination and collaboration, including intelligence sharing.

Bolster government engagement with local communities. A consistent lesson from NGOs in Niger and Burkina Faso is that engaged governmental presence in local communities can allow governments to regain support from communities where their authority has been challenged by militant Islamist groups. This means that in Mali and Burkina Faso, improving relations between civilians and security forces must be a priority, and in Niger these relations should be deepened. Supporting a more professional armed forces directly contributes to the success of military operations on the ground and the trust that local communities place in the defense and security forces.14

By responding to FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam in ways that have sometimes violated human rights and abused local populations, Malian, Burkinabe—and to a lesser extent, Nigerien—armed forces may have pushed some vulnerable individuals to join these groups for protection or revenge. To prevent the reiteration of such damaging actions, it is critical that security responses be implemented in ways where armed forces show the highest level of professionalism and where civilian authorities ensure a constant and close oversight of the security forces’ engagement. Similarly, for any peacebuilding initiative to be effective, security forces must be trusted to ensure the safety of actors involved in peace and intercommunal talks.

Improve the capacity of authorities to deliver justice. Reinforcing the perception that justice is possible will help to restore trust between communities and their governments. Effective and equitable application of justice signals to citizens that violent extremist groups will face repercussions for the instability that they have caused in society. Justice also entails accountability for corrupt government officials and security actors who commit human rights abuses (even if in the name of combatting terrorism).

Very few of the massacres committed in central Sahel have been thoroughly investigated. Even fewer perpetrators have been brought to justice. In different ways, FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam have leveraged this narrative to convince some individuals that the best solution is to exact justice on their own terms. Strengthening the investigative capacities of the judiciary and security forces in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger is therefore crucial. Injustice and the state’s alleged lack of impartiality are essential aspects of the narratives promoting violent extremism. Delivering justice through proper sentences and legal decisions will reduce support for militant groups.

“[Security forces] should be equipped with the necessary staff and resources to address complaints of human rights violations.”

Creating a gendarmerie prévôtale (military judicial police) or equivalent service would establish the authority for enforcing judicial processes within the armed forces deployed in conflict-affected zones. The gendarmerie and police should be equipped with the necessary staff and resources to address complaints of human rights violations. Performing these functions will strengthen institutional legitimacy and provide evidence of governments’ commitment to rule of law. Specified troops might be designated “human rights referents,” prior to and during any operation. Such a designation would provide those troops with the responsibility of ensuring that the provisions of armed conflict and international humanitarian law are observed.

Members of the gendarmerie prévôtale should also be responsible for gathering evidence and pursuing the investigation of suspects, including those arrested on terrorism charges by the armed forces. This would help guarantee that suspected individuals face due process and, if necessary, proper sentencing and thus limit the chance that terrorists go free due to lack of incriminating evidence.

Counter radical narratives that exacerbate social tensions. FLM, ISGS, and Ansaroul Islam have used various media platforms to promote a radical discourse and to spread an extremist interpretation of Islam that advocates for violence. Amadou Koufa is believed to have been radicalized by the Pakistani Dawa sect, a group which funded mosques and madrasas in Mali during the 2000s and adheres to an anachronistic-vision of Islam.

To tackle the ideological component of militant Islamists’ approach, therefore, will require working with religious leaders to establish and implement guidelines regulating the funding of religious education and activities. This should be complemented by efforts to amplify voices of nonviolence, which have long been the norm in the Sahel.

Tracking external funding and, where necessary, banning funding that supports groups, schools, or religious institutes that promote violence would help prevent the diffusion of extremist narratives. Such actions would help convey messages of peaceful coexistence within and across religious communities and prevent disaffected members of society from feeling that violence is their best means of expression.

Pauline Le Roux was a visiting Assistant Research Fellow at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies from 2018 to 2019.

Notes

- ⇑ Pauline Le Roux, “Confronting Central Mali’s Extremist Threat,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 22, 2019.

- ⇑ Pauline Le Roux, “Exploiting Borders in the Sahel: The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 10, 2019.

- ⇑ Pauline Le Roux, “Ansaroul Islam: The Rise and Decline of a Militant Islamist Group in the Sahel,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 29, 2019.

- ⇑ This brief focuses on violent extremism in the central Sahel and thus excludes violence around the Lake Chad Basin in southeast Niger or western Chad.

- ⇑ Interview with the Association des éleveurs peuls du Tillabéri in Niamey.

- ⇑ “A Review of Major Regional Security Efforts in the Sahel,” Infographic, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 4, 2019.

- ⇑ Interview with the Haute autorité pour la consolidation de la paix (HACP) in Niamey.

- ⇑ Interview with the Centre de suivi et d’analyses citoyens des politiques publiques (CDCAP) in Ouagadougou.

- ⇑ Fransje Molenaar, Jonathan Tossell, Anna Schmauder, Rahmane Idrissa, and Rida Lyammouri, “The Status Quo Defied: The Legitimacy of Traditional Authorities in Areas of Limited Statehood in Mali, Niger and Libya,” CRU Report (The Hague: Clingendael Netherlands Institute of International Relations, 2019).

- ⇑ Ernest Uwazie, “Alternative Dispute Resolution in Africa: Preventing Conflict and Enhancing Stability,” Africa Security Brief No. 16 (Washington, DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2011).

- ⇑ Interview with Cercle d’études de recherches et de formation islamique (CERFI) in Ouagadougou.

- ⇑ Wendy Williams, “Shifting Borders: Africa’s Displacement Crisis and Its Security Implications,” Research Paper No. 8 (Washington, DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2019).

- ⇑ Helmoed Heitman, “Optimizing Africa’s Security Force Structures,” Africa Security Brief No. 13 (Washington, DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2011).

- ⇑ Mathurin C. Hougnikpo, “Africa’s Militaries: A Missing Link in Democratic Transitions,” Africa Security Brief No. 17 (Washington, DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2012).