At the heart of Burundi’s political crisis is the issue of protecting the Arusha Accords, a political framework widely attributed with having brought Burundi out of its 1993–2005 civil war. Indicative of the centrality of these Accords, a broad-based opposition political coalition has called itself the National Council for the Restoration of the Arusha Accords.

But why exactly are the Arusha Accords so central? How has the CNDD-FDD related to these agreements historically? And what implications does this have for the current crisis?

What Is the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement?

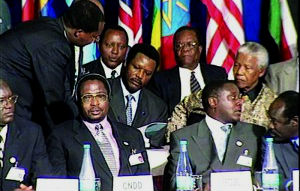

The Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement, otherwise known as the Arusha Accords, was signed in August 2000 after protracted negotiations facilitated by former Presidents Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Nelson Mandela of South Africa. It ended 12 years of civil war and cycles of massacres, including genocide, dating back to Burundi’s independence in 1960. The war pitted Hutu rebels against successive Tutsi-dominated regimes. “For many Tutsis, control of the military was seen as vital for their physical survival as a minority. While for the majority Hutus, the Tutsi-dominated army was the main obstacle in realizing their political rights,” notes Dr. Nicholas Haysom, a key member of President Mandela’s mediation team. “When President Nyerere launched the talks in 1998, we focused on the assassination in 1993 of the first democratically-elected Hutu president, Melchior Ndadaye by Tutsi officers,” explains Joseph Butiku, a senior member of President Nyerere’s mediation team. “Initially we tried to get some agreement on restoring the democratic institutions that had been overthrown but with time it became clear that we needed to go deeper, to examine the fundamental nature of the conflict and then devise modalities to restructure the Burundian state in ways that responded to the root causes.”

The Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement, otherwise known as the Arusha Accords, was signed in August 2000 after protracted negotiations facilitated by former Presidents Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Nelson Mandela of South Africa. It ended 12 years of civil war and cycles of massacres, including genocide, dating back to Burundi’s independence in 1960. The war pitted Hutu rebels against successive Tutsi-dominated regimes. “For many Tutsis, control of the military was seen as vital for their physical survival as a minority. While for the majority Hutus, the Tutsi-dominated army was the main obstacle in realizing their political rights,” notes Dr. Nicholas Haysom, a key member of President Mandela’s mediation team. “When President Nyerere launched the talks in 1998, we focused on the assassination in 1993 of the first democratically-elected Hutu president, Melchior Ndadaye by Tutsi officers,” explains Joseph Butiku, a senior member of President Nyerere’s mediation team. “Initially we tried to get some agreement on restoring the democratic institutions that had been overthrown but with time it became clear that we needed to go deeper, to examine the fundamental nature of the conflict and then devise modalities to restructure the Burundian state in ways that responded to the root causes.”

“Ndadaye’s victory in 1993 was symbolic for Hutus,” notes Willy Nindorera, a Burundian expert on the Arusha peace process. He explains that many were convinced that it was now possible to win greater representation without resorting to arms. The assassination sapped this confidence, replacing it with widespread perceptions that the Tutsi-dominated military was bent on standing in the way of democracy. These realities shaped the mediation strategy pursued by Nyerere and continued by Mandela. Both facilitation teams were mindful of the importance of convincing Hutu opponents that peace talks provided an alternative means to resolving the conflict. Facilitators were equally mindful of the need to disengage Tutsi elites from the calculation that controlling the military was the only guarantee to prevent their community from being annihilated. Events in neighboring Rwanda played heavily into this calculus writes the late Howard Wolpe, an American diplomat who worked closely with both mediators.

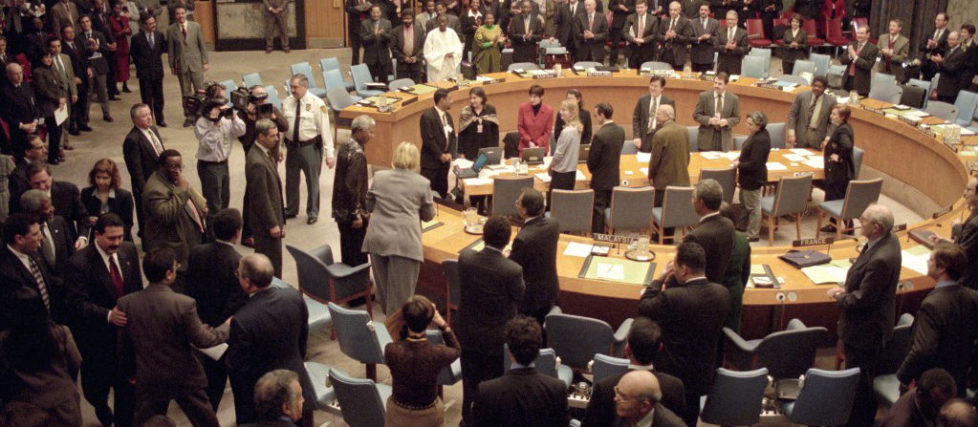

Nelson Mandela in January 2000 is welcomed by the UN Security Council and endorsed as facilitator of the Arusha peace process.

As talks continued the mediation sought to balance two extremely complex questions. The first was how to guarantee full political participation by the minority Tutsi population even when its prospects for winning competitive elections would remain slim in the foreseeable future? The second was how to alleviate the deep mistrust of the Hutu majority in the armed forces? These questions were resolved through four crucial devices:

- A power sharing formula was created based on minority over-representation and coalition-building

- Protocols provided for the equitable participation of all parties in the three branches of government and in all national institutions including state-owned corporations

- Constitutional checks to discourage the concentration of power by a single party or group of aligned parties

- Modalities to integrate former enemies into a more representative military

All these provisions were negotiated separately and after the agreement and ceasefire were signed, they were written into Burundi’s constitution. Accordingly, no single ethnic group constitutes more than 50 percent of the defense and security forces. Similarly no ethnic group holds more than 67 percent of local, county and municipal positions. Across cabinet ministries, the diplomatic service, and the institutions supporting democracy such as the National Electoral Commission (CENI), Constitutional Court, National Assembly, and National Commission on Human Rights, the party in power cannot enjoy more than 60 percent representation.

Arusha Accords under Threat

While these compromises engendered coalition-building and helped dilute old antagonisms, some chafed at the restrictions imposed. “Hardliners in the ruling party are questioning these provisions … they seem determined to expand their control over the political and military institutions—something which the Arusha Accords specifically outlaw,” notes Burundi scholar Thierry Vircoulon. He contends: “the real challenge of the current crisis is to decide whether or not to maintain the Arusha framework.” Former Burundian President Domitien Ndayizeye agrees: “The biggest problem is not the third term per se but rather an effort by the ruling party to remove references to the Arusha Agreement.”

Events preceding the crisis validate many of these concerns. In February 2014, First Vice President and top UPRONA official Bernard Busokoza was removed from office after opposing a decision by the CNDD-FDD–appointed interior minister to remove the UPRONA party leader and replace him with a CNDD-FDD sympathizer. Three UPRONA cabinet ministers promptly resigned, ending the party’s role as a junior coalition partner, a power sharing mechanism that had been in place since 2005. Since then, the CNDD-FDD has been effectively governing the country on its own. In March 2014 it unsuccessfully attempted to pass legislation which would have altered the power sharing arrangements, proposing inter alia to abolish the two vice president posts (one for the ruling party and the other from the opposition) and replacing them with a powerful prime minister appointed by the ruling party. It similarly failed to pass a proposal allowing the president to contest a third term.

Defeated in parliament, the CNDD-FDD put the matter of the third term before party members in early April 2015 ultimately winning endorsement, but not before several leading members walked out in opposition. In the party’s April 24, 2015, announcement that Nkurunziza would seek a third term, the CNDD-FDD claimed, “Some of the Arusha provisions are invalid and cannot be used to resolve the current crisis … these provisions were declared null and void by the Global Ceasefire Agreement.” The party was referring to South African-mediated ceasefire accords that the CNDD-FDD signed in 2003 when it was still a rebel group. However, the chief mediator of these accords, former South African president Thabo Mbeki, disagrees with this interpretation, explaining that the ceasefire provisions flowed from the Arusha Accords and should be read together. In his view, Burundians cannot afford to dismantle these Accords, as the alternative could be civil war.

Defeated in parliament, the CNDD-FDD put the matter of the third term before party members in early April 2015 ultimately winning endorsement, but not before several leading members walked out in opposition. In the party’s April 24, 2015, announcement that Nkurunziza would seek a third term, the CNDD-FDD claimed, “Some of the Arusha provisions are invalid and cannot be used to resolve the current crisis … these provisions were declared null and void by the Global Ceasefire Agreement.” The party was referring to South African-mediated ceasefire accords that the CNDD-FDD signed in 2003 when it was still a rebel group. However, the chief mediator of these accords, former South African president Thabo Mbeki, disagrees with this interpretation, explaining that the ceasefire provisions flowed from the Arusha Accords and should be read together. In his view, Burundians cannot afford to dismantle these Accords, as the alternative could be civil war.

Historical Factors Shaping How the CNDD-FDD Relates to the Arusha Accords

Knowledge about CNDD-FDD’s evolution is key to understanding the current crisis. The movement was formed in the aftermath of the assassination of the first democratically elected Hutu president, Melchior Ndadaye in 1993 by Tutsi partisans in the military. Its ideological origins however are rooted in purges of Hutu officers and intellectuals by Tutsi military leaders during the upheavals of the 1960s and ‘70s. The worst of these upheavals occurred in 1972 following a failed coup by Hutu officers.

These reprisals caused an exodus of Hutus, leading to the formation in exile of the Party for the Liberation of the Hutu People (PALIPEHUTU). Its philosophy was inspired by the “Hutu power” ideology of the Movement for the Liberation of Hutu People (PARMEHUTU), then Rwanda’s ruling party. These historical events weigh heavily on the Burundian collective conscience. For Hutus they symbolize subjugation. For Tutsis they invoke memories of ethnic reprisals by their Hutu neighbors.

Civil war was launched in earnest following Ndadaye’s assassination. CNDD-FDD, like other armed movements including PALIPEHUTU, saw itself as a champion of the Hutu cause. However, it suffered from internal upheavals stemming from differences over ideology, strategy, and tactics. Its original members were followers of Ndadaye and his Front for Democracy in Burundi (FRODEBU). They saw the 1993 crisis as political, not ethnic and espoused a multiethnic vision closely associated with Ndadaye’s politics.

Other members of CNDD-FDD, primarily those who defected from the more radical PALIPEHUTU, retained a highly ethnicized interpretation of the larger Burundian conflict. Still others rallied around a multi-ethnic vision but maintained that Hutus, not Tutsis, should be the primary participants in the struggle. These ideological differences affected the movement’s coherence. On some issues, the ethnic element was more pronounced, reflected for instance in attacks against Tutsi civilians to avenge reprisals by the military against Hutus. On other issues, moderate tendencies prevailed such as the movement’s successful attempts in later years to woo Tutsis.

When President Nyerere launched the Arusha peace process in 1998, the CNDD-FDD had split into three factions and Pierre Nkurunziza, then the top commander of the movement, was battling to control the largest of these. The mediation team barred him from the negotiating table until he reconciled his movement and negotiated with one voice, a demand that his fellow commanders considered “patronizing.” The movement’s relationship with the mediation team as well as with regional countries became increasingly acrimonious. This reinforced an acute dislike of perceived regional “bullying,” which is emblematic of the deeply embedded Burundian cultural aversion to outside interference.

As a result, the movement remained outside the Arusha negotiations and did not sign the Accords. It constantly sought an alternative mediation framework, in the process incurring sanctions from countries in the region. Kenya at one point restricted CNDD-FDD members transiting through its territory. The Regional Initiative on Burundi, led by Uganda, declared the movement a “negative force,” a designation that technically exposed it to regional military action. Tanzania restricted the movement’s access to Burundian refugee camps on its territory, which were a major source of revenue and support. Tanzania at one point even granted the Burundian military the right of “hot pursuit” in case CNDD-FDD fighters crossed into its territory. These pressures, coupled with skillful diplomacy by Nelson Mandela, and his successor Thabo Mbeki, incentivized CNDD-FDD to negotiate a ceasefire in good faith in 2003.

A CNDD-FDD rebel gives up his weapon in Mbanda, Burundi, February 2005.

The movement, seeing an opportunity to win future elections, projected itself as moderate and recruited several respected Tutsi intellectuals on its negotiating team. After joining the Transitional Government late 2003 it sold itself as an alternative to PALIPEHUTU and won over many skeptics. It included among its top leadership several prominent Tutsis and campaigned on a multi-ethnic platform. Nkurunziza identified himself with this moderate ideological outlook and was even nicknamed “Umuhuza” (the unifier). Yet, more conservative elements in the party resented this shift in the party’s outlook. They also disliked the regional pressure piled on it and have regularly voiced displeasure with the Arusha Accords since. “These people treated us like boys,” a senior CNDD-FDD leader complained shortly after the party won the 2005 parliamentary elections.

CNDD-FDD Posture toward Arusha Going Forward?

CNDD-FDD’s victory in the 2005 elections assuaged some of its misgivings about the Arusha process. Adhering to the stipulations of the Accord, the party’s cabinet line-up was impressive for its ethnic inclusiveness, professionalism, and experience. Thus, even though it was not a signatory to Arusha, the CNDD-FDD created an image of a multi-ethnic movement. It reached out to civil society and the media, some of which embraced and helped propagate the party’s new vision countrywide.

Over time, however, consensus-seeking became strained. Two factors might account for this. The first and most immediate is that the Accord’s extensive checks and balances were an inconvenient obstacle to the quest for a third term and greater political control. The second factor centers on the resentment within the CNDD-FDD over having to share power in the first place. Supporters of this view now saw an opportunity to institutionalize the party’s dominance. The calculus was that the party’s future survival was best guaranteed by greater political control, even if this meant overturning the Arusha Agreement.

Signs of a crisis over Arusha, however, were evident as far back as the disputed elections in 2010 which, as in 2015, were boycotted by the opposition and also marked by violence. Thus, there were multiple missed opportunities to confront the CNDD-FDD on its adherence to Arusha before the third term crisis.

A ceasefire is signed by President Nkurunziza (right) and PALIPEHUTU-FNL leader Agathon Rwasa in September 2006.

A 2012 International Crisis Group report reads like it might have been written in 2015: “Control of all institutions by the ruling party makes the power-sharing system defined by Arusha irrelevant … the only checks and balances are the media and civil society.” The major differences in 2015 are that the media has been largely destroyed, a much larger number of opposition politicians are in exile, over 200,000 refugees have fled the country, and many in the opposition are now entertaining the idea of armed struggle.

“The Burundian government and other stakeholders [must] find a consensual political solution to the grave crisis facing their country,” warned the chairperson of the African Union, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma. How the principles of Arusha are upheld will go a long way in determining if such a consensus can be achieved.

Additional Resources

- “Burundi: Bye-Bye Arusha?” International Crisis Group, Africa Report No. 192, October 25, 2012.

- Adelin Hatungimana, Jenny Theron and Anton Popic, “Peace Agreements in Burundi: Assessing their Impact,” Africa Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), Conflict Trends, Issue 3, 2007.

- Willy Nindorera, “The CNDD-FDD in Burundi: The Path from Armed to Political Struggle,” Berghof Foundation, Transition Series from Liberation Movements to Political Parties, No 10, 2012.

- Kristina A Bentley and Roger Southall, “The Arusha II Negotiations: From Nyerere to Mandela” in An African Peace Process: Mandela, South Africa and Burundi, Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa (HSRC), 2005.

More on: Burundi Leadership Rule of Law