The phenomenon of migrants traversing the hostile terrain of northern Africa to Europe is not new—not the routes or the dangers. A decade ago, experts estimated that about 2,000 migrants drowned each year attempting to cross the Mediterranean and untold numbers perished in the desert. But after the collapse of the Gaddafi regime in 2011, the number of people crossing the Mediterranean from Libya (the Central Mediterranean route) has grown exponentially—resulting in a 277 percent increase since 2013.

In fact, 60 percent of all migrants caught illegally entering Europe in 2013 came on boats from Libya. On those boats, nearly half were Syrians (39,651) and Eritreans (33,559) who were granted “protection status,” provided to persons fleeing conflict or persecution or for other humanitarian reasons. As a result, they received residence permits, access to employment, education, and healthcare among other benefits.

Sub-Saharan migrants contributed the next largest cohort (26,340) crossing the Mediterranean from Libya. Only a fraction of these received protection status as they were deemed to be “economic migrants”—those merely seeking to improve their standard of living.

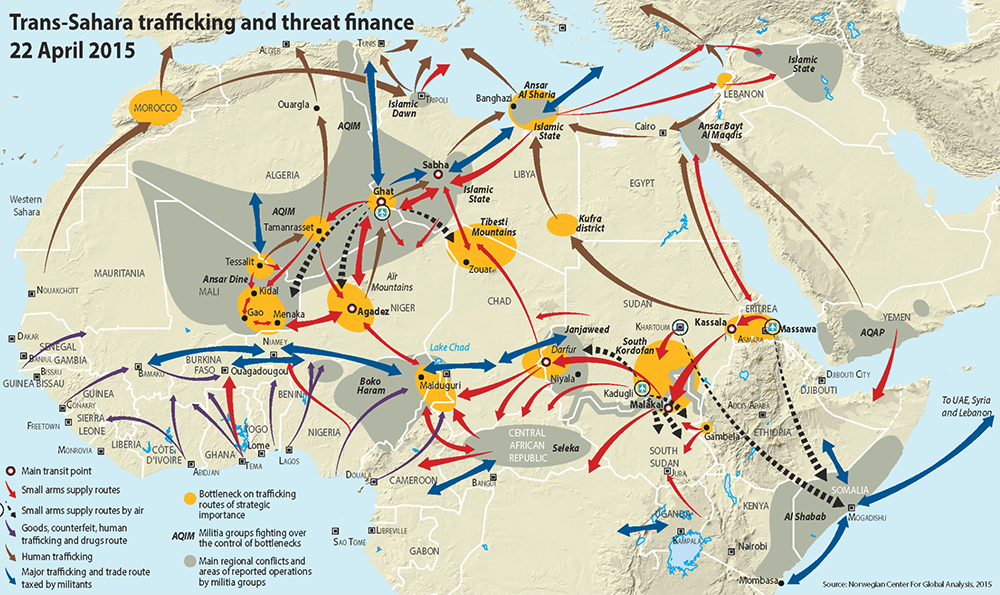

Whether fleeing conflict or persecution or seeking to improve one’s standard of living, many African migrants converge on the same Central Mediterranean route (see graphic below).

With many Sub-Saharan countries facing an expanding youth bulge, the number of African migrants is likely to rise in the coming years. Indeed, more young migrants than ever (including a growing number of women and minors as young as 14) are embarking on the risky journey toward Libya’s coast.

Transnational criminal and terrorist networks benefit most from the migration flows

As migrants make their way across the desert and eventually the Mediterranean, they increasingly face exploitation and abuse at the hands of transnational criminal rings and extremist groups. Trafficking and torture of Eritrean migrants is well documented in Sudan and Egypt. As criminal and terrorist groups have found control over these smuggling and trafficking routes to be highly lucrative, their role in this illicit activity can only be expected to grow.

Source: Norwegian Center for Global Analysis, 2015.

In response to the rising demand, the migrant smuggling economy has bloomed. On Libya’s coast it is valued at $255–323 million a year and dwarfs Libya’s other illicit enterprises. The fees migrants pay for safe passage to Libya and beyond do not just go to small-time smugglers. Various groups also charge a “protection” tax for anyone crossing their path. For many migrants coming through West Africa, their money finds its way into the hands of terrorist groups like al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), al Mourabitoun (formed by Mokhtar Belmokhtar), Ansar Dine, and Ansar al Sharia who control swaths of territory through Algeria, Libya, Mali, and Niger. Migrants coming from the Middle East, increasingly encounter the Islamic State (IS), which has attacked refugee camps in western Syria to increase the flow of Syrians south toward Egypt through IS-controlled territories for the purpose of raising revenue.

Extortion of migrants is just one way criminal and terrorist networks benefit from gaining a foothold in fragile countries. The lasting damage they do to these societies is another. As organized crime becomes rooted in areas where state security and judicial institutions are weak or corrupt, it becomes far more difficult to eradicate. For many of these areas the illicit economy brings one of the only means of subsistence. Eventually, the communities become more disposed toward the criminal activity at the expense of rule of law.

The entrenchment of organized criminal and terrorist groups in the vacuum provided by weak government control has already been seen in parts of northern Mali and Niger, southern Algeria, and in Libya. This, in turn, diminishes economic investment (and job prospects) as well as the space to build state structures, democracy, and stability.

Priorities for Action

Much of the focus on the Central Mediterranean migration crisis has been on the heightened European efforts at interdiction. Likewise, much of the instability in Libya is viewed through the lens of the growing influence of terrorist groups like the Islamic State. However, the intertwining of the migration crisis and terrorist groups highlights other priorities such as:

Stabilization

Stabilizing Libya is central to stemming the immediate migration crisis. Doing so will also directly affect an important source of revenue going to the Islamic State and other terrorist and criminal groups that are exploiting the crisis for their financial gain.

The migration crisis also shines a light on the desperation of citizens living under repressive African states such as Eritrea. International diplomatic and humanitarian engagement in Eritrea and other authoritarian states in Africa can help address a key segment of the Central Mediterranean migration crisis at its source.

Raising the Costs on Human Smugglers

External efforts must also focus on criminalizing migrant smuggling—not the migrants. Central to these efforts will be the need to raise the cost and risk for smugglers. Reinstating an effective police presence, which used to exist under Gaddafi’s regime, would discourage smugglers who now don’t even feel the need to hide their human cargo. Niger also recently placed legal responsibility on transport “companies” to ensure their travelers have valid documents. Otherwise, these groups are at risk of having their assets confiscated.

Better Information for Source Migrant Communities

For the migrants and the communities through which they pass, more information and direct assistance is necessary. UNHCR, for example, has set up skills training and awareness-raising workshops for Eritrean migrants in Ethiopia to dissuade them from continuing onward to Europe. The EU has plans to set up a presence in Agadez, a hub of West African migration, to tackle the smuggling economy that has infiltrated every aspect of this central Nigerien town.

Additional Resources

- Altai Consulting, Mixed Migration: Libya at the Crossroads: Mapping of Migration Routes from Africa to Europe and Drivers of Migration in Post-revolution Libya (UNHCR, 2013).

- Libya: a growing hub for Criminal Economies and Terrorist Financing in the Trans-Sahara, The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (May 2015).

- Mark Shaw and Fiona Mangan, “Illicit Trafficking and Libya’s Transition: Profits and Losses,” Peaceworks 96, US Institute of Peace (2014).

- Organized Crime and Illicit Trafficking in Mali: Past, President and Future, The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (January 2014).

- Tim Midgley, Ivan Briscoe, and Daniel Bertoli, Identifying Approaches and Measuring Impacts of Programmes Focused on Transnational Organised Crime, Saferworld (May 2014).

More on: Countering Violent Extremism Migration