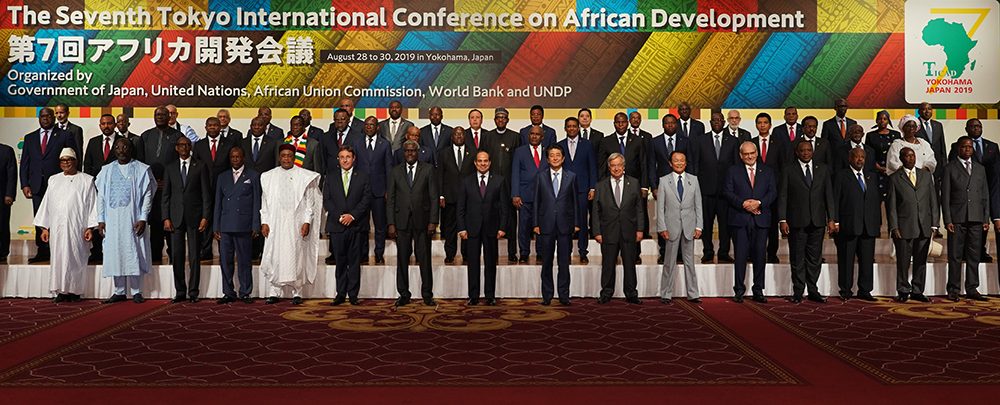

Heads of State at TICAD 7 in Yokohama. (Photo: 写真撮影)

African countries are gearing up for the 8th Tokyo International Conference on Development (TICAD), commonly known as the Japan-Africa Forum, in Tunisia on August 27-28. Nearly 50 African leaders are expected to attend, along with over 200 African civil society and NGO representatives, 108 heads of regional and international agencies, and 120 leaders of trade, industry, and technology innovation—making it one of the biggest hybrid diplomatic events in Africa since COVID. TICAD is also Asia’s leading investor in African peace and security with an annual portfolio of over $350 million.

Co-hosted with the United Nations, the United Nations Development Program, the World Bank, and the African Union Commission, TICAD is distinctive for its multilateral and multisectoral emphasis. Efforts to advance the Sustainable Development Goals in Africa are explicitly linked to peacebuilding, constitutional development, justice system reform, and democratic governance. This year’s dialogue will focus on achieving sustainable and inclusive growth, human security, and building African capacity for sustainable peace and stability.

TICAD responds to African priorities on the basis of ownership—jinminshoyū (人民所有)—a core principle of Japanese partnership. Rather than just a series of triennial summits, TICAD represents a process of ongoing engagement. During its 30 years of existence, Japan has trained thousands of Africa’s engineers, entrepreneurs, and educators. Many Africans call TICAD a model mechanism for international cooperation and security cooperation.

To capture the unique aspects of the TICAD dialogue, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies reached out to nearly a dozen African and Japanese specialists* who have contributed to TICAD over the years for their insights and experiences.

What Is TICAD?

TICAD started in 1993, making it the oldest forum of its kind. Its multilateral co-partnerships, called Hōkatsu-tekina 包括的な in Japanese (“all encompassing”), distinguish TICAD from the Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), which “hardly involves other multilateral actors,” says Hannah Ryder, a former Kenyan and British diplomat who advises African countries on partnership with Southeast Asian nations.

TICAD also includes civil society, NGOs, and professional bodies based on merit (Ataisuru, 値する, or “to be worth”) not through vetting by ruling parties as is the case with China’s FOCAC. Denis Matanda, who advises the Common Market for East and Southern Africa (COMESA) on international strategy, says this enhances popular engagement and ownership.

TICAD session on Human Capital Development/Education for Youth. (Photo: Ken Katsurayama)

TICAD underscores Japanese solidarity with Africa. According to the late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, “In the 1990’s when much of the international community had forgotten Africa, Japan believed in Africa, and launched TICAD.” Indeed, in the lead up to TICAD, many Africans are mourning Abe, one of its key architects. They have eulogized him as an “ally,” “brother,” and “special friend and partner” who had a “special love and affection for Africa.” At TICAD 7 in 2019, Abe pledged to incentivize the Japanese private sector to invest $20 billion in Africa, for infrastructure and human resources—a target Japan has largely achieved.

TICAD is also part of a postwar Japanese foreign policy that seeks to cultivate a new Japanese international identity of peace, outlined in the Preamble of Japan’s Constitution, which states that: “We desire to occupy an honored place in an international society striving for peace, and the banishment of tyranny and slavery, oppression and intolerance for all time from the earth.” Ambassador Erastus Mwencha, the former Deputy Chairperson of the African Union Commission, observes that “TICAD underscores Japan’s peaceful intentions, gives Africa an alternative, and convinces us that we matter to Japan and our issues would not be ignored internationally.” Ambassador Mwencha worked with seven Japanese Prime Ministers and was decorated with Japan’s highest honor, the Order of the Rising Sun, for his efforts.

There are several benefits for Japan: to advance Japanese soft power, development models and technologies, gain market share, marshal African diplomatic support in international forums, and build new security alliances for Japan.

How is TICAD Organized?

TICAD meets triennially on rotation between Japan and Africa. It is more than a regular summit, though, as the summits are part of an ongoing process of engagements and initiatives. TICAD meetings often feel like the World Economic Forum, where government, business, and civil society leaders participate on an equal basis. Each TICAD round sets priorities and implementation plans for the next three years.

The TICAD Unit within the UNDP Headquarters in New York provides technical support for the day-to-day implementation at national and regional levels in between conferences. Japanese and African civil societies participate at all levels through bodies like the Africa Japan Association, Japan Africa Business Forum, and Japan Africa Public Private Forum hosted by the UN Industrial Development Organization. This mirrors the Japanese practice of ringi-sho (稟議 書)—loosely translated as “bottom-up”—where proposals are discussed widely before endorsement.

“Japan’s programs are built around four elements: social inclusion, youth strengthening and capacity building, human security and ownership, and institutional and policy reforms, including elections.”

TICAD focuses on three pillars: society, economy, and peace and stability through human security. Its sectoral areas align with African strategic priorities like the African Peer Review Mechanism and Agenda 2063.

In the area of peace and security, TICAD has worked with the African Union over the past 20 years to provide financing and technical assistance to eight peacekeeping training centers of excellence, deployed Japan Self Defense Force (JSDF) training teams to eight African peacekeeping troop contributing countries, trained over 5,000 judicial officers to assist with justice and rule of law reform in 54 countries, and sent JSDF advisors to support African troops in non-combat roles in peace missions in Somalia, Mali, Sudan, and South Sudan.

Democratic governance is a crucial piece of the TICAD engagement model. According TICAD’s “New Approach to Peace and Security in Africa” African conflicts are rooted in the manner in which political power is exercised, which for the most part is arbitrary and highly personalized. This governance structure prevents independent institutions from performing their constitutional functions. It also results in the political, economic, and social exclusion of large sections of the population—especially women and young people, who constitute the majority.

Japan’s programs, thus, are built around four elements: social inclusion, youth strengthening and capacity building, human security and ownership, and institutional and policy reforms, including elections.

Former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo at TICAD 6 in Nairobi. (Photo: Office of the President of Rwanda)

Japan’s commitments to democratization makes the choice to host the next TICAD in Tunisia awkward for many Japanese actors. According to Shinichi Takeuchi, the Director of the African Studies Center at the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, “We see some tendencies toward authoritarianism in Tunisia as shown by the recent protests against the draft constitution which creates a highly centralized presidential system and undermines the democratic trajectory since the Ben Ali regime was removed.” Takeuchi says “many Japanese involved in African affairs are very sensitive to Japan being perceived as strengthening undemocratic actors and governments. We are concerned that Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s presence in Tunis could send a wrong message about our firm commitment to democracy and good governance in Africa and around the world.”

What Aspects of the Strategic Partnership Have Been the Most Distinctive?

The ABE Initiative (Master’s Degree and International Program on African Business Education Initiative), an outcome of TICAD 5, inspired by Shinzo Abe, is arguably TICAD’s most iconic program. It brings hundreds of African students to Japan each year to train in Japan’s top graduate schools. Along with other Japanese scholarship schemes such as the Japan Africa Dream Scholarship (initiated by African Development Bank) and the prestigious Monbukagakusho.

These initiatives also support Japanese students’ understanding of Africa. The Global Leadership Training Program, for example, brings Japanese graduate students to Africa annually for extended training direct by African supervisors to develop viewpoints and address issues from an African perspective.

Another TICAD flagship program, the Enhanced Private Sector Assistance for Africa Initiative (EPS4A) was co-founded in 2005 by Japan and the African Development Bank (ADB) to develop Africa’s private sector. It has invested over $13 billion on a 50-50 basis, signifying strong African co-ownership.

“TICAD is distinctive for its focus on peacebuilding.”

TICAD is also distinctive for its focus on peacebuilding. The Triangular Partnership Project for African Rapid Deployment of Engineering Capabilities (ARDEC) trains African peacekeepers on maintaining and servicing heavy equipment. Through a partnership with UNESCO’s International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa, TICAD also supports the incorporation of peace education into African educational curricula from high school to the university level. In the current program cycle, the “Consolidation of Peace Program” focuses on supporting civil society actors, mainstreaming youth and women’s empowerment into all development programming, and supporting human rights institutions.

How Have Africans Exercised Agency?

TICAD’s 50-50 funding model with the ADB underscores Japan’s approach of treating partners as agents, not mere recipients. This is called sōgokankei (相互 関係)—emphasizing mutuality. Ambassador Mwencha notes that “donor/recipient relations are inherently asymmetric. However, Japan’s insistence on co-ownership allows African stakeholders to exercise greater agency than with others.” According to Hannah Ryder, Africans also exercise more agency because TICAD involves non-African and non-Japanese partners. “They [Africans] can get those partners to co-finance infrastructure projects or use their procurement power to encourage Japanese firms to invest in African manufacturing among other things.”

Since TICAD 1, African civil society and NGOs have made their voices heard through direct participation in UNDP’s TICAD Multisectoral Dialogues where they participate on an equal footing with government officials. Ahead of each round, TICAD invites applications from non-governmental bodies to participate in a month-long program of exchanges at the meeting venue, making the summit part of a longer program of citizen engagement.

African governments often remain too passive, however, says Hannah Ryder. “They tend to allow the other party to set the agenda, only coming in when there are red lines, of which there are usually none. Hence there is a need for stakeholders to push for a clear African position, drawing lessons from what independent Africa-China Working Groups did ahead of FOCAC 8, which shaped the AU’s strategy.”

Africans can also assert agency through the private sector. Jean-Claude Maswana, an economics professor at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto who has advised Japanese investors and the Japan International Cooperation Agency, contends that TICAD should gradually phase out the summit and continue focusing on bridging African and Japanese businesses and professionals. “Summitry is far less frequent in the Southeast Asian model than it is in Africa, and this is a key lesson for the AU. Southeast Asia’s economic transformation and industrialization was not driven by governments, but private sector and professionals. It is they who meet frequently, including across borders. Governments only come in after being lobbied by private sectors to enact enabling policies, provide subsidies and other incentives, negotiate favorable bilateral instruments, and work towards peace and stability.”

Greater African agency is also needed to change Japanese risk averse perceptions of Africa. Japan-African trade is modest at $24 billion per year. However, Japan’s approach to FDI and economic development seeks to be qualitatively different. According to Shinichi Takeuchi, “Japan’s capital investments seek to: keep Africa’s debt burdens low, empower and strengthen African private sectors, and involve beneficiaries in identifying priorities.”

“Slowness and hesitation are in our [Japanese] genes, but when we come in, it is good and long lasting. We don’t just want to get in and get out.”

Denis Matanda agrees: “I think Japan’s assistance to COMESA provides a model. I can attest to the fact that beneficiary countries and stakeholders are involved at every stage. The Japanese side also seems to dislike creating dependency. If you look at Japan’s activities in automobile technology, you will find forward and backward linkages, such as maintenance and spare parts right here in Africa. And most of the Japanese technologies in Africa are sourced and exported by Africans, from cities like Osaka and Kobe, where African exporters have established themselves since the late eighties.”

“This is where Japanese-trained African professionals can be key, if only they are involved in efforts to woo Japanese investors and engage the Japanese government more strategically,” says Phillip Olayoku of the African Association of Japanese Studies in Nigeria. “Japan’s approach is very unique” says Kenichi Ohno of the Tokyo-based National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. “African countries have to be patient. Slowness and hesitation are in our [Japanese] genes, but when we come in, it is good and long lasting. We don’t just want to get in and get out.”

What Are African Priorities Beyond TICAD 8?

African countries are focused on economic transformation and conflict resolution, meaning that Agenda 2063 and Silencing the Guns 2030 will be the main frameworks going forward. Accordingly, four broad elements will shape the TICAD partnership. First, is the continuing need to close Africa’s infrastructure gap—a key pillar of Agenda 2063. Japan’s influence in the G7’s Build Back Better World (B3W) could help unlock finance while keeping debts low.

Recent TICAD logos and locations.

The second priority is value-addition, which will require Japanese firms to invest up the value chain to boost the quality of African exports.

The third is to operationalize the African Standby Force Mechanism—as a tool that can contribute to conflict resolution. At TICAD 7, Japan committed itself to supporting the AU’s “Silencing the Guns” Initiative. Supporting conflict resolution efforts in five designated priority geographic regions—the Horn of Africa, North Africa, Sahel, Sudan and South Sudan—is a central feature of this line of effort.

Finally, African stakeholders will be looking for ways to increase their strategic engagement by pushing to better leverage TICAD’s unique strengths in human resource development, technology transfer, and private-sector capacity building. TICAD is conducive to this as it is structurally designed to allow citizen inputs.

*Expert contributors to this synthesis:

- Ambassador Erastus Mwencha is the Former Deputy Chair of the African Union Commission and key TICAD architect on the African side.

- Naohiro Kitano shaped key elements of TICAD as the Former Director of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Research Institute and Development Assistance at the Japan Bank for International Cooperation.

- Denis Matanda is the President of Morgenthau Stirling and advises the Common Market for East, Central, and Southern Africa (COMESA) on international strategy.

- Hannah Wanjie Ryder is the CEO of Development Reimagined and advises African countries on cooperation with Southeast Asian nations.

- Shinichi Takeuchi is the Director of the African Studies Center at the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

- Jean-Claude Maswana is an Economics Professor at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, Japan.

- Phillip Olayoku coordinates the West African Transitional Justice Center and is a member of the African Association of Japanese Studies in Nigeria.

- Kenichi Ohno is an Economics Professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo.

- Paul Nantulya is a Research Associate at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies and participated in TICAD 3 and the TICAD Conference on Promoting Peace in Africa.

Additional Resources

- Hannah Ryder and Ivory Kairo, “Four Goals for Africa at Japan’s TICAD8 in Tunis,” African Business, June 27, 2022.

- United Nations Development Programme, “Multi-Sectoral Dialogue Ahead of TICAD 8 Discusses Emerging Priorities and Challenges in Africa,” Read Out, June 21, 2022.

- Daisuke Akimoto, “TICAD: The Evolution of Japan’s Africa Diplomacy,” The Diplomat, March 31, 2022.

- Kyodo News, “Japan, African Ministers Stress Importance of Democracy, Rule of Law,” Briefing, March 28, 2022.

- Aissatou Kante, “Could Japan Give New Direction to West African Security Approaches?,” Institute for Security Studies, ISS Today, March 8, 2022.

More On: External Actors in Africa