Between March 2016 and December 2017, there will be at least 52 presidential and parliamentary elections in 38 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. With memories of the intense violence following the elections in Kenya (2007), Zimbabwe (2009), Côte d’Ivoire (2010), and Nigeria (2011), many international and regional institutions have become more focused on understanding the motivations and triggers for electoral violence.

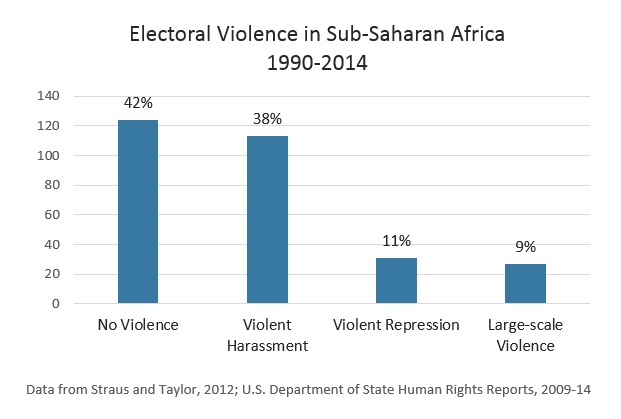

Research of electoral violence between 1990 and 2007 by Scott Straus and Charles Taylor and additional data from the U.S. State Department’s 2008–14 Human Rights Reports provide a sense of the scope and type of electoral violence predominant in sub-Saharan Africa. The data tell us that the likelihood of electoral violence varies greatly across the continent. Many countries experience no electoral violence, while others have intensely violent elections. Moreover, the risk of violence can differ from year to year within the same country.

This data, which categorizes four levels of electoral violence, may help predict those countries most at risk for future election-related conflict (see table). Between 1990 and 2014, 42 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s presidential and parliamentary elections were peaceful—free of harassment, intimidation, and violence. For countries holding elections between 2016 and 2017, this category includes Cabo Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe, and the Seychelles. Another 38 percent of elections in Africa, including Gabon, the Gambia, and Ghana, experienced low-intensity violence—mostly harassment and intimidation. In 11 percent of cases, harassment and intimidation resulted in fatalities (less than 20). Cameroon, Madagascar, and Senegal are the countries holding elections in 2016 and 2017 that fall into this category. Finally, there are countries where elections almost always result in intense violence and more than 20 fatalities. They account for 9 percent of all elections and include the Democratic Republic of Congo and Kenya.

In short, elections in Africa over the next two years present a wide range of challenges to regional and international actors striving for credible, free, and fair elections on the continent. The cases of Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Ghana illustrate the obstacles faced.

A History of Violence: Kenya

The 2013 election in Kenya attracted broad international, regional, and domestic efforts to stave off a repeat of the 2007 electoral violence, in which 1,300 people died and 650,000 were displaced. Critical stakeholders began preparations early. The passage of the 2010 constitution was among the most important reforms, requiring improvements to the accountability and administration of the judicial sector, electoral commission, and national police; the creation of a land commission; and the devolution of Kenya’s 8 provinces into 47 counties. These reforms were meant to address perceived and real ethnic biases in justice, governance, economic prosperity, and security—longstanding grievances that had contributed to cycles of violence in the past. As a result of all these efforts, violence was dramatically reduced from 2007. The national discourse was, similarly, less virulent, with many organizations monitoring hate speech. Still, more 400 Kenyans died and 100,000 were displaced in the run-up to the 2013 election as a result of clashes at the subnational level.

Kenya’s current political context raises concerns for violence surrounding its August 2017 elections, where voters may elect as many as 1,880 officials. While 2013’s devolution created some development gains, it also resulted in increased opportunities for candidates to assert extralegal means to secure victory as well as exacerbate perceptions of ethnic bias in political power. Furthermore, leading opposition members, questioning the impartiality of the electoral commission, have begun weekly protests across the country. Equally worrying is the resurfacing of the Mungiki gang, which was implicated in some of the 2007–08 post-election violence. Finally, the unraveling of the International Criminal Court case against President Uhuru Kenyatta, Deputy President William Ruto, and others accused in the 2007–08 violence, weakens the threat of sanctions for violence.

Combined, these elements leave open the door for the manipulation of grievances for political ends and a tense, even violent, contest in 2017. Preventing electoral violence in Kenya will depend on:

- Establishing avenues for early warning of conflict and strategies for an effective early response to defuse the situation

- Sending strong signals from national leaders that planning and carrying out acts of election-related violence will be punished

- Careful monitoring and reprimands of hate speech

Early Signs of Trouble: DRC

The Democratic Republic of Congo is scheduled to hold presidential and parliamentary elections in November 2016, but it remains uncertain if they will take place then. Due to a shortage of funding, the electoral commission only began the process of preparing for the polls in February. The commission’s main objective, developing a new voters’ register, is estimated to take 16–17 months to complete.

Apart from the funding shortfall, many suspect that President Joseph Kabila intends to stay on beyond his two terms, an issue that led to deadly clashes between protesters and security services in January 2015. Mindful perhaps of how badly forcibly imposed term extensions have fared elsewhere—for instance, in Burkina Faso—Kabila has called for a national dialogue on constitutional issues, including the election. But most of the political opposition see this as another effort by Kabila to postpone the elections. Moreover, the government’s engagement with opposition supporters continues to deteriorate, as security forces have detained a number of civil society activists and opposition party candidates.

The opposition, meanwhile, appears able to rally its supporters, as the relatively successful February 2016 ville morte (general strike) demonstrated. This may help opposition parties should the election date slip past November. The recent ruling by the Constitutional Court, permitting Kabila to remain in place after November 2016, until a successor is sworn in, bears a disturbing resemblance to the judicial permission received by Burundi’s president, as he sought a third term. Thus, against the backdrop of Burundi’s third-term crisis, international, continental, and regional institutions will need to take steps now to prevent the escalation of violence. Importantly, the African Union must glean lessons from the failed intervention in Burundi to develop a robust consensus on the way forward in the DRC, identify credible mediators, and exercise meaningful leverage to sanction the violation democratic norms.

Worrisome Trends: Ghana

Ghana has usually received praise for its successful and relatively peaceful political transitions. In 2008, just 40,586 out of 9,001,478 votes cast separated the ruling National Patriotic Party’s (NPP) Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo from the winner, the National Democratic Congress’ (NDC) John Atta Mills. Yet, Akufo-Addo and the NPP accepted the results. Many attribute the peaceful handover to the credibility of the electoral commission (EC), Ghana’s internalization of democratic values, and the reliability of the parallel vote tabulation by civil society, which served as a check against the official results. Similarly, while the NPP legally contested the 2012 elections that reelected NDC incumbent President John Mahama, Akufo-Addo and the NPP respected the decision of the Supreme Court when it ruled in favor of Mahama. Once again, Ghana’s institutions had shown their strength as viable mediators of political conflict.

Heading into the December 2016 presidential and parliamentary elections, however, worrying developments in the EC, the judiciary, and the security services may point to an erosion of Ghana’s democratic progress. The Supreme Court’s months-long hearing of the 2012 presidential election results revealed troubling deficiencies in the EC’s training of officers and management of the electoral process, raising questions about its integrity. Recently, the NPP called for a new voter list, alleging that 76,000 foreigners registered as Ghanaian voters in 2012. The EC initially declined to compile a new register, but the Supreme Court ordered it to develop a new voters registry, calling the existing one not credible. The judiciary also suffered a significant blow when in September 2015, undercover reporter Anas Aremeyaw Anas released a documentary showing 34 judges taking bribes to reduce sentences. With the documentary’s release, the once highly esteemed institution was seen by some to be indisputably corrupted. Then in March 2016, three South Africans were arrested for training the security detail assigned to Akufo-Addo and Mahamudu Bawumia, NPP’s presidential and vice-presidential candidates, respectively. Whereas the security services charged the South Africans for conspiracy, the NPP claimed their candidates felt unsafe in Ghana, hence the need for additional training.

As a result of the mounting tension, some national and international leaders have called for a national dialogue to defuse the situation. Such discussions should occur regularly to map out a way forward and ensure that all political parties have confidence in the process. Additionally, the constitutionally created National Commission for Civic Education, which led a series of conflict management and peacebuilding activities in early 2016, has a critical role to play. Finally, past successes, such as the parallel vote tabulation and the National Election Security Task Force, should be robustly supported.

Conclusion

While many African electoral contests in the coming years will proceed without violence, there are countries whose history and institutional weaknesses make them vulnerable. The cases reviewed here show that governmental and civil society efforts can effectively mitigate electoral violence. However, as 95 percent of all incidents of electoral violence takes place within six months of polling day, support from the international community is most effective when provided early. International organizations should prioritize programming that strengthens early warning and conflict mitigation actors so that they can play these roles effectively. Early warning, in turn, should elicit early response.

Additional Resources

- Dorina Bekoe, “Preventing Electoral Violence: Greater Awareness, but Still Falling Short,” USIP Insights, Winter 2015.

- Stephanie Burchard, “The Resilient Voter? An Exploration of the Effects of Post-Election Violence in Kenya’s Internally Displaced Persons Camps,” Journal of Refugee Studies (2015), 28 (3): pp. 331–49.

- Emilie M. Hafner-Burton, Susan D. Hyde, and Ryan S. Jablonski, “When do Governments Resort to Election Violence?” British Journal of Political Science, January 2014, Volume 44, pp. 149–79.

More on: Democratic Republic of the Congo Ghana Kenya Rule of Law South Sudan Uganda Youth Bulge