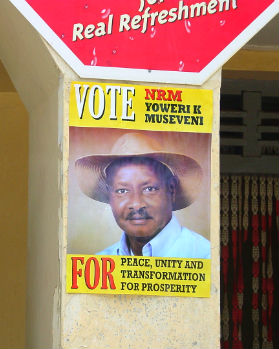

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. (Photo: Russell Watkins/Department for International Development)

The July 26 Constitutional Court ruling that approved the lifting of the presidential age limit of 75 from Uganda’s constitution has cleared the way for 73-year-old Yoweri Museveni to run for a sixth term in 2020. A series of protests, arrests, and violent episodes involving the security sector has revealed a level of instability in Uganda that has caught many observers by surprise.

The arrest of a leader of the movement to retain the age limit, opposition member of Parliament and musician Robert Kyagulanyi (popularly known as Bobi Wine) on August 13 sparked widespread protests, leading to the arrests of over 100 people and the deaths of 2 civilians, including Wine’s driver. The unrest intensified after pictures emerged of Wine being carried into court after allegedly being beaten while imprisoned. He and a group of more than 30 parliamentarians have been charged with treason in a military court for allegedly instigating crowds to stone the president’s motorcade. While the charges were later moved to a civilian court, the attempted use of military justice to prosecute a civilian has fueled anger. Four journalists covering the case were arrested and beaten and had photos deleted from their cameras.

Bobi Wine. (Photo: Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu)

In a further bid to stem the unrest, the government arrested opposition leader Kizza Besigye and dozens of other lawmakers on August 23. They have been held under a controversial measure known as “preventative detention,” which allows security forces to arrest persons suspected of planning demonstrations.

Grievances over the removal of the age limit can be traced back to the February 2016 elections, when a civil resistance movement known as Togikwatako—“Don’t you dare touch [the constitution]”—was launched to galvanize Ugandans to stop the ruling party from tampering with the constitution. Several hundred of its members were arrested in a series of protests that started in Kampala shortly after the elections. They had spread across the country by the end of 2017. Nonetheless, in December 2017, nearly 90 percent of the Parliament voted to scrap the age limit, largely due to the ruling National Resistance Movement’s (NRM) control of the body. Even as the measure was being debated, protests erupted in the assembly and across Uganda. Six legislators were suspended for launching a filibuster, and physical brawls broke out in front of the cameras. Special Forces raided the building in an effort to quash the filibuster in violation of parliamentary rules that protect the premises from intervention by the security forces. In the scuffle, soldiers assaulted MP Betty Nambooze, breaking her back. The regular police and military police subsequently disrupted demonstrations in Kampala and other cities.

These events have exposed the growing tensions surrounding Uganda’s political stasis. They have also worsened the generational divides in Uganda’s political process. Nearly 70 percent of Uganda’s population is under 30, and youth unemployment remains persistently high. It is these disenfranchised youths that have been mobilized by Togikwatako and Bobi Wine, 36, and who make up the majority of the protesters.

Sowing Divisions

The lifting of the age limits was the second time Uganda’s laws have been amended to prolong Museveni’s rule. In 2005, term limits were eliminated, impairing a constitution that was once hailed as a model of participatory constitution-making and institutional innovation. The effects have caused a fracturing within Uganda’s political class.

Within the NRM, the controversy around constitutional limits on the executive is linked to the divisive issue of the president’s succession. The removal of term limits in 2005 destabilized the party, leading to the ouster of some of President Museveni’s top lieutenants, including Kizza Besigye, a former senior army officer who now leads the opposition Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). Internal tensions continued in the run-up to the February 2016 polls when former party Secretary General and Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi launched an unsuccessful bid to unseat Museveni as party chairman and state president. The bitter fallout continued after the polls. In October, NRM “rebel legislators,” who the president later described as “parasites,” called on him to abandon his efforts to lift the age limit.

(Photo: Laura)

In an effort to curb more unrest, the chief government whip in parliament, Ruth Nankabirwa, announced in May 2018 that dissenting party members would face disciplinary measures. Later that month, the NRM fired all of its nearly 500 employees, purportedly to bring under control the debts that had been incurred during the party’s campaign to remove the age limit. Some members, however, saw it as an orchestrated plot to purge the NRM of malcontents. In the run-up to the 2020 elections, party tensions will continue to mount as uncertainty over the succession grows.

The over-concentration of presidential power has been a central issue in Ugandan politics since its independence. All eight presidents who served between 1966 and 1985 seized power undemocratically and were themselves violently removed from office. When Museveni’s NRM captured power in 1986, it was cognizant of this tragic history and identified abuse of executive power as the source of the country’s turmoil. Its cadres at the constitutional talks therefore championed the inclusion of term limits in the 1995 Constitution. Museveni himself set the tone. In his book, “What Is Africa’s Problem?” which was published after he assumed office, he wrote, “The problem of Africa and Uganda in particular is leaders who want to overstay in power.”

“The over-concentration of presidential power has been a central issue in Ugandan politics since its independence.”

The president and his allies now argue that Uganda needs predictable leadership much more than term limits. Opponents, on the other hand, invoke Museveni’s earlier argument that the term limits themselves are crucial for stability. This link is supported by historical experience. Analysis by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies finds that a third of the 18 African countries that lack term limits are facing armed conflict. This includes the 10 that, like Uganda, have had such limits overturned. Not coincidentally, the average time in office for chief executives in countries lacking term limits is 22 years. For those with term limits, the average is four years. President Museveni’s 32-year tenure fits this pattern.

The Politicization of State Institutions

The Constitutional Court’s 4-1 ruling was criticized by some of the drafters of the 1995 constitution for undermining a central tenet of Uganda’s constitution-making process: “Orderly and peaceful changes of leadership at all levels should be embedded in Uganda’s traditions.” It had also been a pillar of the Ten Point Program, the NRM’s own strategic blueprint for recovery, which was established in the 1980s and is still ostensibly government policy.

The controversy over presidential succession has also been felt in the Uganda People’s Defense Forces (UPDF), long seen as among Africa’s most professional militaries. Shortly after the 2016 elections, 30 mid- and high-ranking officers were arrested over an alleged coup plot. They were accused of colluding with an FDC parliamentarian with links to the Togikwatako movement, which many in the NRM suspect may have found some sympathy in military circles. In 2016, Besigye got more votes than Museveni in many NRM strongholds, including constituencies such as Luweero and Kasese, where many NRM war veterans are concentrated. Notably, Besigye also got more votes in the military police barracks in Kampala, from which soldiers are routinely called to quell protests.

“The UPDF is now led by officers in their early 40s who have few ties to the liberation war but are fiercely loyal to the president.”

Disquiet in the military over moves to change the constitution date back to the removal of term limits in 2005. The stiffest opposition to the president came from his allies in the NRM’s Military High Command. They included the late Prime Minister and NRM co-founder Eriya Kategaya, former Assistant Minister of Defense Amanya Mushega, and Mugisha Muntu, Uganda’s longest serving defense chief—all of whom joined Besigye in the FDC. Army generals, such as the former coordinator of intelligence, Gen. David Sejusa, openly rebelled and were expelled from the party. Others from this cohort were retired during the massive reshuffle of January 2017 at the height of the Togikwatako campaign. The UPDF is now led by officers in their early 40s who have few ties to the liberation war but are fiercely loyal to the president.

The ruling has also made the succession issue more intractable. With no limits to executive incumbency, the decision to leave office is now solely at the president’s discretion. Unlike South Africa’s African National Congress or Namibia’s Southwest African Peoples Organization, the NRM does not have the structures that would enable successful challengers to emerge. Some critics have even argued that the ANC’s removal of two presidents from office—Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma—was an eye-opener for Museveni’s allies, who are now more determined than ever not to allow their party to function independently or develop mechanisms to check its leaders.

The independence of the judiciary has also been called into question. The courts have ruled in the president’s favor in most cases that potentially jeopardized his incumbency. The 2016 unanimous ruling by the Supreme Court to uphold his re-election, despite allegations that electoral laws weren’t followed, is a case in point. The 2001 and 2006 petitions, which gave evidence of falsified results and widespread irregularities, produced split decisions (3-2 and 4-3, respectively). In both instances, then-Chief Justice Benjamin Odoki cast the deciding vote in favor of the executive, despite the court agreeing that there were “serious irregularities.”

The courts have not always been this deferential, however. In a landmark 2005 ruling, the Constitutional Court nullified the restrictions placed on political parties other than the NRM, paving the way for the reintroduction of multiparty politics. In 2007, in the midst of multiple counterinsurgency operations, the High Court dismissed the state’s application to reverse the bail granted to suspected insurgents.

Public confidence in the courts is at an all-time low.

Despite episodic displays of judicial independence, public confidence in the courts is at an all-time low. A 2015 Afrobarometer survey found that the police and judiciary are perceived to be the two most corrupt institutions in Uganda. Indeed, the FDC did not even petition the courts over irregularities in the 2011 elections and instead launched long-running protests. Today, civil disobedience is the preferred method of the opposition. That is unlikely to change given the Constitutional Court ruling lifting age limits.

What Next?

(Photo: Andrew Regan)

Many Ugandans fear that the judiciary and Parliament will be weakened further by an overbearing president with unlimited power. The executive is likely to continue relying heavily on its parliamentary supermajority to pursue its agenda (the NRM holds 293 out of 426 seats). In November 2004, the opposition Democratic Party questioned the diversion of $1.3 million from the National Social Security Administration to NRM lawmakers in exchange for their support in lifting term limits. When Parliament debated lifting the age limit in December 2017, ruling party deputies inserted a clause that extended parliamentary terms from five to seven years in exchange for their support. This deal, however, was thrown out by the Constitutional Court in a ruling a day before its decision on removing presidential age limits. The court called the proposed extension “greedy.” It is still unclear whether NRM lawmakers will continue to push the matter as a precondition for their continued support of the president’s agenda.

On the judicial side, the sponsors of the petition to the Constitutional Court are mulling taking the case to the Supreme Court, though that court too is perceived to lean toward the NRM. Its ruling on Museveni’s victory in 2016 was handed down despite the fact that the petitioner, Amama Mbabazi, had his home and office raided by police a few days before the trial.

The age limit ruling has further weakened checks and balances on Uganda’s already powerful executive. The closing of options for a legal means for peaceful succession is heightening tensions within society, especially among youth. Lessons from Uganda’s turbulent history suggest that accountable governance, not military prowess, is ultimately the country’s best guarantee for stability.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Term Limits for African Leaders Linked to Stability,” Infographic, February 3, 2018.

- Samuel Gebre and Omar Mohammed, “Rising Authoritarianism Threatens Democracy in East Africa,” Business Day, October 16, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “African Role Models in Strategic Leadership,” Spotlight, May 11, 2016.

- Joseph Siegle, “Why Term Limits Matter for Africa,” blog, Center for Security Studies, July 3, 2015.

- Mathurin C. Houngnikpo, “Africa’s Militaries: A Missing Link in Democratic Transitions,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 17, January 31, 2012

More on: Rule of Law Uganda