The preparation of leaders for higher policy and command responsibilities at the strategic decision-making as well as operational levels is a major requirement for success in the effective and sound management of state affairs and strategic policy, a panel of international officials said at the Africa Center’s Senior Leaders Seminar on June 9, 2014.

The African continent in the past decade has witnessed exponential growth in the development of Staff and Command Colleges, Public Service Training Schools, Diplomatic Training Schools, and National Defense Colleges, an indicator that more attention and resources are being directed towards improving the quality of leadership as well as the professional and academic foundation of civilian and military leaders.

In the United States, military leader development is provided by three types of schools: the entry-level service academies such as the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York; the intermediate-level schools, such as the Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; and senior schools such as the National War College at the National Defense University on Fort McNair in Washington, D.C. Still, with this well-developed system of schools at the three levels for each of the four branches of the U.S. military, leader development and sustainment remains a continuous challenge and an ongoing learning process even for the United States, American officials said.

African and American Generals reflected on these challenges at the 16th annual Senior Leaders Seminar, hosted by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, which opened June 9, 2014, in Washington D.C. The program was scheduled to run two weeks.

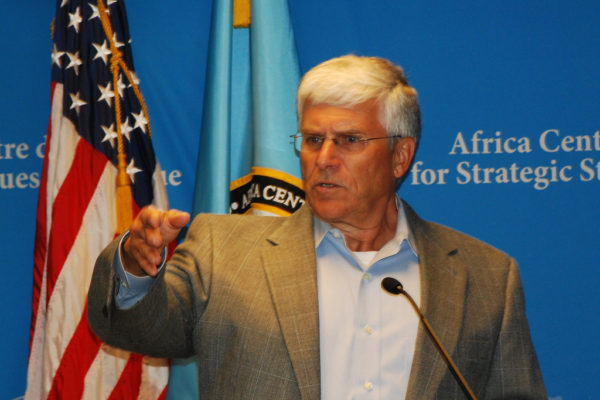

The first panel was led by retired General George Casey Jr., who served as the 36th Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army from 2007 to 2011.

The first panel was led by retired General George Casey Jr., who served as the 36th Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army from 2007 to 2011.

Sharing many anecdotes from his 41-year military career, the retired general who also commanded the Multi-National Force-Iraq, a coalition of more than 30 countries, told participants that leadership principles are the same both in the Army and in the civilian world.

“It comes down to focusing energy on things that will have the highest payout,” he said.

He urged African leaders to focus their time and energy at the right place in order to address the key issues they are confronted with, to always envision and plan for the future, and create milestones together with subordinates so as to create a shared vision and commitment to outcomes.

“People easily become confused by complexity and ambiguity, and as a result they don’t act, which is why it is important to build consensus with colleagues and subordinates at all levels of your organization, including those outside your area of responsibility,” he advised.

General Casey discussed the so-called VUCA model (explained below) as one of many frameworks used in emerging ideas in strategic leadership, a model that continues to be applied in a wide range of organizations, from the military to private corporations and education.

The model is used to reflect on four key issues:

- volatility, which has to do with the nature, dynamics, and speed of change;

- uncertainty, which entails the prospects for surprise;

- complexity, which reflects the confusion that often surrounds decision-making; and

- ambiguity, being aware of, working through and continuously addressing these four issues are vital for success in solving many problems that affect decision making at every level, he said.

The general in his concluding remarks reminded participants about the importance of planning for the future. “Looking into the future also means that you, as leaders, need to invest in growing the future generation of leaders.”

The second part of the program was led by Brig. Gen. Saleh Bala, the former Chief of Staff at the Nigerian Army Infantry Center and Lt. Gen. Kathleen Gainey, a retired U.S. Air Force General who served as Deputy Commander, United States Transportation Command at Scott Air Force Base in Illinois.

General Bala, also a graduate of the National War College at National Defense University in Washington, attributed Africa’s leadership challenges to three issues: poor governance, exacerbated by weak and underdeveloped democratic cultures; lack of data-based and scientific national planning and decision-making; and negative attitudes breeding elitism, nepotism and, ultimately, religious and ethnic-based violence.

The retired general, who also served as former military Chief of Staff for the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI), decried the over-dependence in Africa of the military to resolve disputes.

“We have a situation on the continent,” he reflected, “where the army has evolved to become the most prominent and dominant institution of the state, as a result of which every problem is resolved using military means, including those that can be settled using diplomacy, law enforcement, and other tools of statecraft,” he argued. Further exacerbating the problem, in his view, is that despite its preponderance the military in Africa for the most part is weak, and in many instances suffers from poor leadership.

Consequently the over-reliance of the military instrument has created mistrust between the security services and civilians, and in the process undermined the quest for building more stable and inclusive societies on the continent. A radical shift in thinking in the way the African state is organized is therefore required, according to his presentation.

General Bala noted that the evolution of the security environment in Africa requires much more sophisticated and comprehensive responses that go beyond the mere reliance on the military. He singled out the expansion of terrorism in such places as Somalia, Mali, and now Nigeria.

He argued that terrorists exploit social, economic, ethnic, and religious grievances, which are created in the first place because the social contract between the government and citizens has been broken. The use of combat power alone is therefore a path to failure; to be effective, counter-terrorism operations must rely on the use of all the tools of statecraft, and above all, the social compact between the state and citizens must be restored through targeted social and economic interventions.

“We have to get away from the trap of thinking that because we have a hammer, every problem must be a nail—we need instead invest in other tools of national power,” the general suggested.

He also took issue with Africa’s dependence on outside powers.

“We heard for instance that a foreign power gave millions of dollars to an African country to buy flashlights for its security services. … Now, when you find yourself in a situation where you cannot even provide flashlights for your troops, then something must be horribly wrong,” he argued. The general urged African leaders to be more serious about generating their own resources to manage security challenges. This, he suggested, is one of the ultimate tests of successful leadership.

In terms of operational leadership General Bala singled out the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM), African-led International Support to Mali (AFISMA), and UN missions in Liberia and Sierra Leone as experiences worth studying in greater detail to develop models for how leadership can be exercised in the context of multidimensional and complex peace enforcement operations.

He identified three elements in particular that have been applied to some effect in the three missions: 1) orchestration of the elements of national power; 2) inter-agency collaboration and coordination; and 3) sound civil-military relations.

These lessons, in his view, should be adapted to the national context.

“Here at National Defense University we were drilled with the need to integrate all the elements of statecraft – diplomatic, informational, military and economic—to achieve outcomes, and that is something we as strategic leaders can adapt to the African environment,” he noted.

“To these we should add the Clausewitzian triangle of the army, state, and the people, in order to build stable civil-military relations,” he said. “We should also move away from cosmetic reforms, to real reforms that address the fundamental problems affecting the modern African state.”

Retired U.S. Air Force General Kathleen Gainey focused on the complexities of exercising leadership and sound judgment in a dynamic environment full of ambiguities and surprises.

“In most decision-making environments there are multiple people pursuing multiple interests, divergent views about the nature of problems to be solved, and limited resources to effect desired changes,” she observed. “To operate effectively in such environments, leaders need to correctly define the problem, identify all the players and their interests, and build consensus.”

“If you can map the environment,” the general told her fellow leaders, “and make good use of negotiation and consensus-building, you will be on your way to success.”

Drawing on her experience supporting the delivery of logistics to the war theater, the retired general stressed the importance of flexibility and improvising.

“In one assignment I realized that meeting all my metrics did not necessarily translate to success. … I was arranging for the delivery of items on time, but colleagues in-theater didn’t have enough warehouses, so my deliveries were actually causing problems,” she reflected.

“We therefore changed our delivery schedule to factor in the lack of space, put into motion a plan to acquire more warehouses, and in the process we were eventually able to deliver 11 days faster,” General Gainey said. “It however meant that I had to convince my superiors to change my metric, so as to factor in the necessary changes.”

General Gainey urged participants to bring all their subordinates on board in the planning process, capitalize on success, and communicate effectively and regularly with peers, supervisors, constituents and subordinates.

“Everyone, at every level, from the operational to the tactical, needs to understand the mission and their role in it,” she advised. “If you communicate to your peers in the hope that they will somehow communicate down to their subordinates, you might be in for surprises. … A good leader goes all the way down to the tactical level to inspire the fighters.”

During the question-and-answer session the general summed up her presentation with several themes of advice: 1) Not losing sight of the mission, 2) Focusing on the big issues, 3) Conducting periodic low-level checks, 4) Identifying and resolving problems, 5) Personally checking on progress at every level of the organization and, 5) Looking into the future.

The Africa Center for Strategic Studies, which is hosting the seminar, recognized at its inception in 1999, the need for a senior- level program to complement programs for junior, and intermediate-level military and civilian leaders that it organizes on the African continent and in the United States. The two-week program will shape part of the agenda of the upcoming African Leaders Summit to be hosted by U.S. President Barack Obama in August.