A voting center in Mali. (Photo: MINUSMA/Blagoje Grujic)

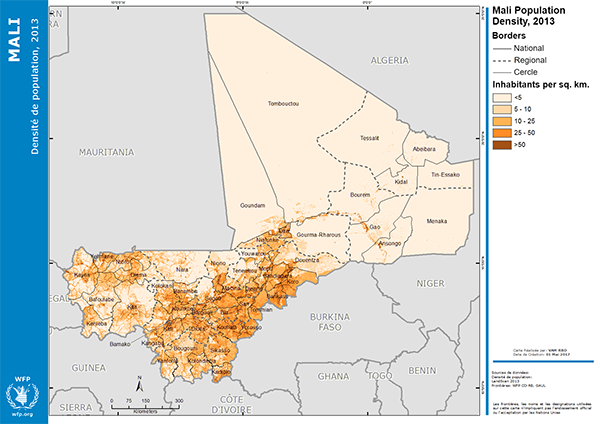

On July 29, Malians voted to elect a new president. The incumbent, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (or IBK, as he is widely known), and 24 other candidates ran in the first round of the election. Since no candidate won more than 50 percent of the vote, IBK, who won 41.4 percent, will face opposition leader Soumaila Cissé, who came in second with 17.8 percent of the vote, in a runoff vote on August 12. The elections take place as Mali continues to recover from a separatist insurgency and military coup in 2012 and ongoing threats from militant Islamist groups in the north that precipitated French and regional military intervention. Ranking 175th on the United Nations Human Development Index, with a population of 18 million—nearly double the size of 2000—and an expansive, land-locked territory of 1.2 million square kilometers (twice the size of France) stretching from the Niger and Senegal rivers in the south to the middle of the Sahara in the north, Mali faces a formidable security geography.

President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. (Photo: Claude Truong-Ngoc)

Meanwhile, political progress since returning to civilian government in 2013 has been mixed. Perceptions of accountability have improved. Thanks to the work of government institutions such as the Bureau du vérificateur général (Office of the Inspector General) and NGO corruption watchdog groups, citizens feel corruption is being exposed. Nonetheless, the capacity of the judicial system to prosecute these newly documented instances of corruption and abuse has not yet been fully developed. So while the percentage of Malians who believe the government is accountable has risen from 57 percent in 2014 to 78 percent in 2017, the percentage of citizens who think the government is effective has decreased from 41 percent to 21 percent, according to Afrobarometer surveys.

Why Are These Elections So Significant?

Mali faces multi-layered security challenges. The country is still recovering from the rupture to its political fabric in 2012. The Tuareg-led insurgency exposed the deep social divisions between the nomadic Berber minority in the sparsely populated and arid north with the more populous and sedentary Mandé ethnic groups (comprising 50 percent of the population) in the more fertile south who have dominated political life in Mali since independence from France in 1960. The ineffectiveness of the military response to this rebellion precipitated a military coup that revealed the weakness of the Malian security sector—and state more generally. These vulnerabilities have been exploited by militant Islamist groups, which for the most part are associated with Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), though the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara has also mounted attacks.

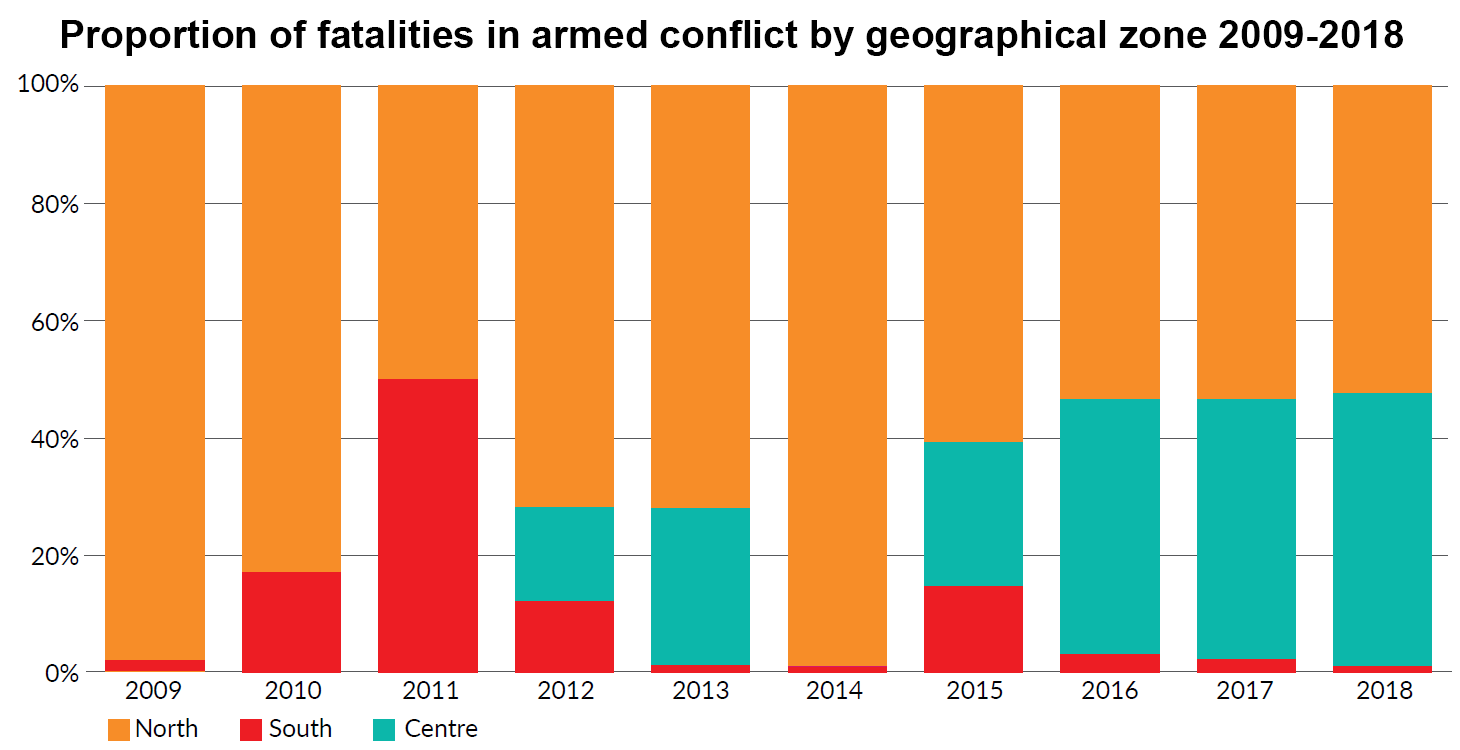

The risk that the militant Islamist groups could sweep into the more populated southern regions of the country, prompted an intervention by troops from France and neighboring African nations in 2013. Mali’s security continues to be bolstered by a UN Mission (MINUSMA), the French Operation Barkhane, and the incipient G5 Sahel Joint Force comprising troops from Mauritania, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso, and Mali itself. Since 2015, the frequency of attacks has increased and shifted to the center of the country.

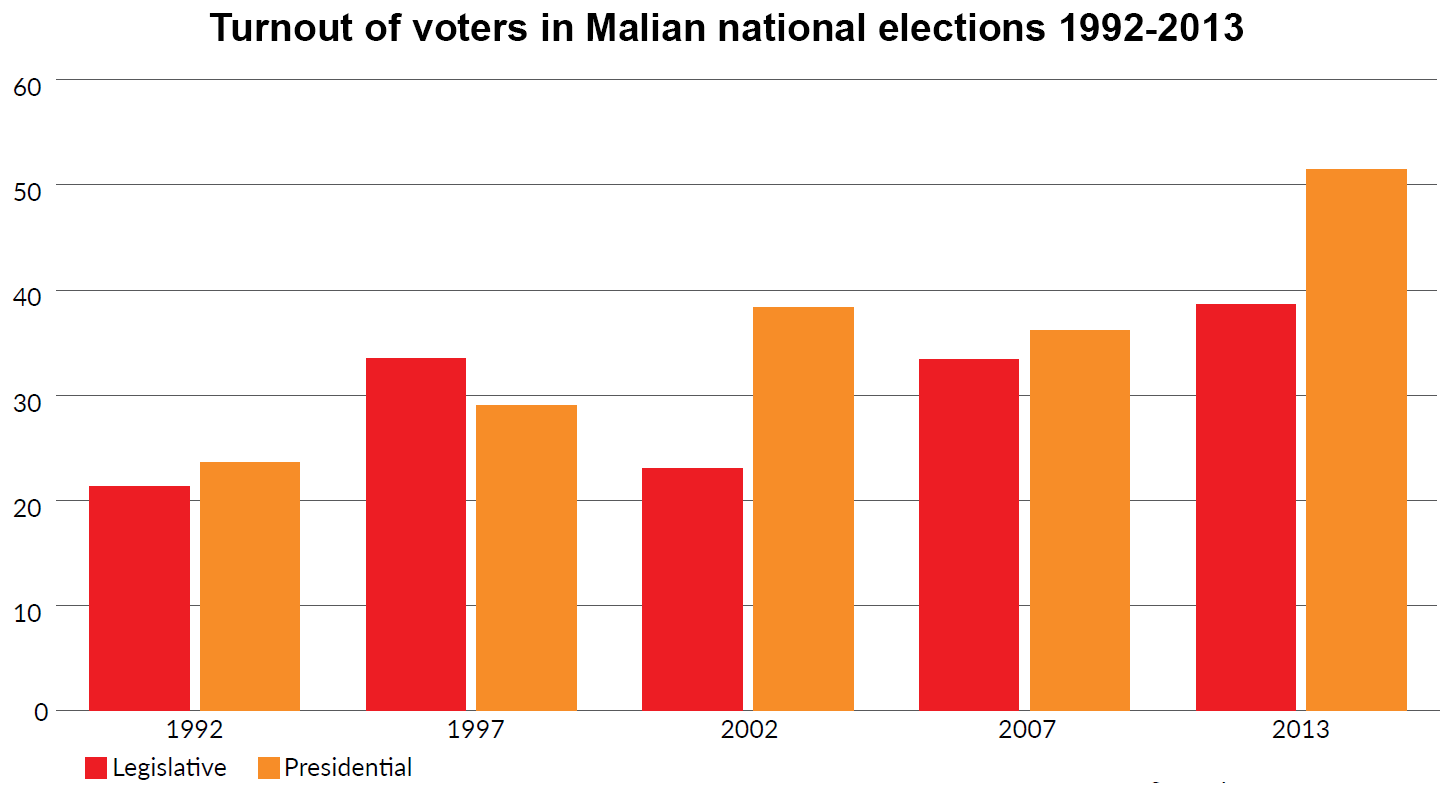

The presidential elections are an important step in rebuilding Mali’s democratic political trajectory, which was established between 1991 and 2012. However, given Mali’s ongoing fragility, the electoral process is fraught with risk. If violence and insecurity sufficiently affect voter turnout, this could lead the opposition and armed groups to question the legitimacy of the election’s outcome. Violence in the north and central regions have made it difficult for authorities to transport and distribute voter cards to citizens in these areas. Moreover, even in Bamako, almost 60 percent of voters have not yet picked up their cards.

What Are the Major Concerns Shaping Citizen Participation?

The threats from militant Islamist groups continue to pose a major concern with fatalities associated with attacks now affecting both the north and central regions of Mali.

Instability still precludes government officials from maintaining a presence across parts of the country. Only 20 percent of sub-prefects deployed in the northern communes in 2017, compared to 36 percent in 2016. In the Mopti, in central Mali, only 33 percent of officials were present at their duty stations.

Source: Richard Reeve.

While the threat in the north comes mostly from militant Islamist groups, in the center of the country, the threat dynamics are multilayered. Ethnicity, farmer vs. herder competition over land, and old tensions between formerly noble and slave social groups contributes to the growing violence in the absence of reliable state security.

In early July, for example, a militia of central Malian traditional Dogon hunters—formed because the hunters and farmers feel threatened by increased tension with nomadic Fulani herders—clashed with Malian security forces after the hunters threatened to prevent the elections from being held. Army soldiers who tried to stop a Dogon gathering and confiscate their weapons burned the hunters’ motorbikes as well. Meanwhile, militant Islamist groups have co-opted and taken advantage of some of these divisions to further destabilize the region and threaten the state.

Largely as a result of the attacks from militant Islamist groups, the government registered 60,600 internally displaced persons, and 590,000 returnees in June 2018, an increase from the previous year. Meanwhile, 137,697 Malians remain refugees in neighboring countries.

The government also faces a challenge of trust with citizens. Afrobarometer surveys suggest that only about half of Malians trust the Independent and Electoral Boundaries Commission. While more than 65 percent of Malians think that democracy is the best form of government, about 60 percent also said they were unhappy with how democracy functions in practice in Mali. Historically, participation in elections in Mali hovers around 40 percent, though it increased to over 50 percent in the 2013 presidential elections. Voter turnout, then, will be an indicator not just of security, but also in citizens’ trust in the political process.

Source: Richard Reeve.

This distrust has been heightened by the fact that some military units have behaved in abusive and predatory ways, including allegations of killing civilians, when they deploy to parts of the country where they were previously absent. This type of behavior makes the security challenge more difficult by feeding extremist narratives regarding the government, despite the fact that some of the militant groups engage in even worse acts against civilians.

Another challenge involves the complex logistical requirements of ensuring that all voting stations have what they need to conduct the vote and that they are secure enough to accommodate voters. For instance, the government is working to increase the number of voting stations by 7,000 so that citizens can be closer to their polling place. MINUSMA is providing support to the elections management bodies, including logistical and technical assistance, as well as organizing voter information sessions. MINUSMA troops will provide additional security on election day. Moreover, the AU, ECOWAS, and the EU are providing observers to observe the entire process. Their ability to certify that the vote went smoothly will be important for giving the process legitimacy.

Prospective voters in Mali are also focused on economic issues, on which most Malians negatively assess their government’s performance. For example, according to Afrobarometer surveys, more than 70 percent say the government has performed badly on job creation, reducing inequality, and improving living standards for the poor. Meanwhile, almost 1 million people will require emergency food assistance in 2018, 55 percent more than in 2017.

What Is the Status of Reconciliation Efforts?

The 2015 Algiers Accord for Peace and Reconciliation (so named because it was negotiated in Algiers) was signed in Bamako by the government and two coalitions of rebel groups, the Coordination des mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA) and the Plateforme des groups armés (the Platform). The Accord forms the basis for reconciliation efforts in the north. The now former rebel groups no longer want to establish an independent “Azawad” in the north, but the Accord provides for more autonomy in the region’s governance and administration and a means to begin reconciliation. In short, the signatories resolve existing political and socioeconomic grievances. Since the Accord, elements from these groups sometimes fight alongside the regular army.

Signing ceremony of the 2015 Algiers Accord.

The signatories agreed to work on creating the conditions for lasting and just peace in Mali by working on four main areas:

- The development of national and regional political institutions (including the establishment of a second chamber in Parliament and the holding of local elections to form local assemblies and manage regional affairs)

- Defense and security reform (including disarmament and demobilization, restructuring of the security sector, and the deployment of Malian security forces across the country)

- Economic and cultural development

- Justice, reconciliation, and humanitarian issues

Showing progress in implementing the Accord, even if it’s limited, is important because it shows a commitment to peace. Conversely, the failure to implement significant portions of the agreement, despite holding the Conférence d’entente nationale or continuing to hold meetings of the Comité de suivi de l’accord d’Alger (the Accord Follow-up Committee), suggests lack of progress, political will, and even bad faith on the part of the signatories.

A key challenge for the new administration will be to address the grievances that drive conflict in the central regions.

The political opposition, as well as several non-signatory groups, argue that the slowness of the Accord’s implementation shows that the IBK Administration is merely going through the motions and is less interested in adhering to the terms of implementation as in keeping itself in power.

The Algiers process did not include stakeholders from the center of the country, even areas that were temporarily occupied by rebel groups in 2012. Moreover, the implementation process does not apply to those regions. Given the increasing insecurity in the central regions, a key challenge for the new administration will be to address the grievances that drive conflict there and work toward effective reconciliation across the country.

What Needs to Happen for These Elections to Translate into Sustained Stability for Mali?

Elections are just one juncture in the ongoing challenge for stability in Mali. Nonetheless, they can be transformative if the results are seen as conveying legitimacy on those elected. National leaders could then be empowered to make the difficult choices needed to advance reconciliation, pursue reforms, and set priorities among the many competing interests facing the country.

Importantly, the winner must commit to continuing to overcome societal divisions by implementing the Algiers Accord and other reconciliation efforts. Mali remains a weak state. Stabilizing it requires a continued responsiveness to the needs of marginalized communities, implementing reconciliation initiatives, and extending the effective presence of the state across the country. This will include renewed efforts to strengthen the capacity and oversight on the country’s security sector institutions as well as enhanced trust and closer ties between government officials and local communities throughout the country.

Africa Center Experts

- Alix Boucher, Assistant Research Fellow

- Dorina Bekoe, Associate Professor of Conflict Prevention, Mitigation, and Resolution

Additional Resources

- Richard Reeve, “Mali on the Brink: Insights from Local Peacebuilders on the Causes of Violent Conflict and the Prospects for Peace,” Peace Direct, July 2018.

- Fadimata Haidara and Thomas Isbell, “Popular Perceptions of Elections, Government Action, and Democracy in Mali,” Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 217, July 4, 2018.

- United Nations Security Council, Report of the Secretary General on Mali, S/2018/541, June 6, 2018

- The Carter Center, “Report of the Independent Observer: Observations on the Implementation of the Agreement on Peace and Reconciliation in Mali, emanating from the Algiers Process, Observation Period: January 15 to April 30, 2018,” May 28, 2018.

- Jonathan Sears, “Mali’s 2018 Elections: A Turning Point?” Bulleting FrancoPaix, Vol. 3, No. 4, April 2018.

- Aurélie Campana, “Entre déstabilisation et enracinement local: Les groupe djijadistes dans le conflit malien depuis 2015,” Centre FrancoPaix, March 2018.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The G5 Sahel Joint Force Gains Traction,” Spotlight, February 9, 2018.

- Arthur Boutellis and Marie-Joëlle Zahar, “A Process in Search of Peace: Lessons from the Inter-Malian Agreement,” International Peace Institute, June 2017.

More on: Democratization Stabilization of Fragile States Mali