COVID testing center in Madagascar. (Photo: World Bank/Henitsoa Rafalia)

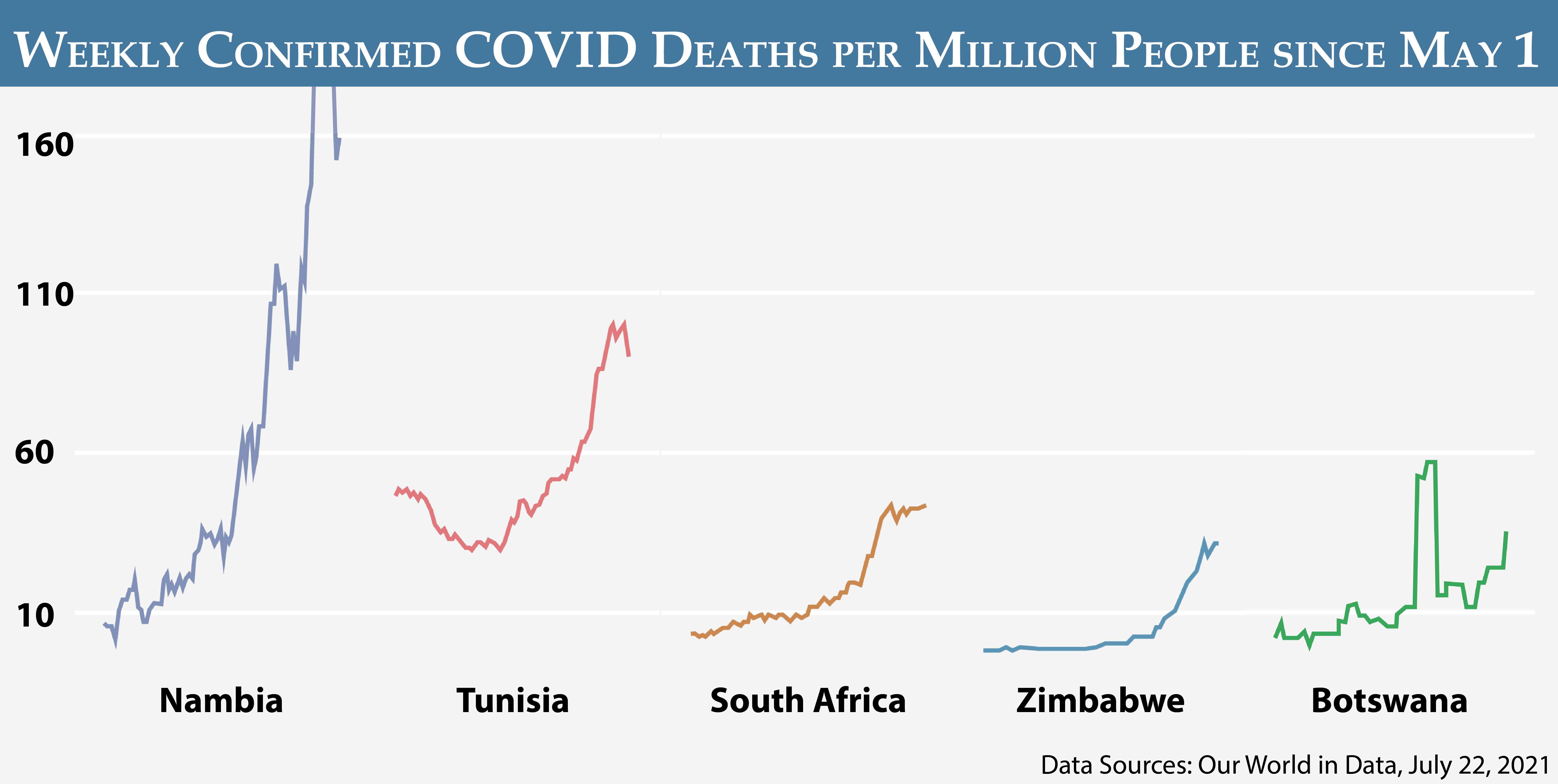

Africa is experiencing a dramatic and predictable spike in COVID cases and fatalities as the Delta variant gains traction. Cases are increasing in 26 African countries, and case fatality rates in Africa are among the highest in the world. Namibia, where only 1.2 percent of the population is vaccinated, is currently experiencing 1 death for every 22 cases (or 4.5 percent). By comparison, in the United Kingdom, where 50 percent of the population is fully vaccinated, the recent case fatality rate is 1 out of every 750 cases (or 0.1 percent).

“Cases are increasing in 26 African countries, and case fatality rates in Africa are among the highest in the world.”

As a continent, Africa is currently experiencing 6,500 COVID-related fatalities per week, and that rate is rising by 43 percent per week. Following this trajectory, Africa is expected to suffer over 150,000 fatalities in the next 2 months. This is in addition to the 160,000 confirmed COVID-related deaths since the start of the pandemic. Given limited testing, this figure is surely an underestimation. Studies of excess mortality in India suggest a mortality rate tenfold higher than the official death toll of 414,000.

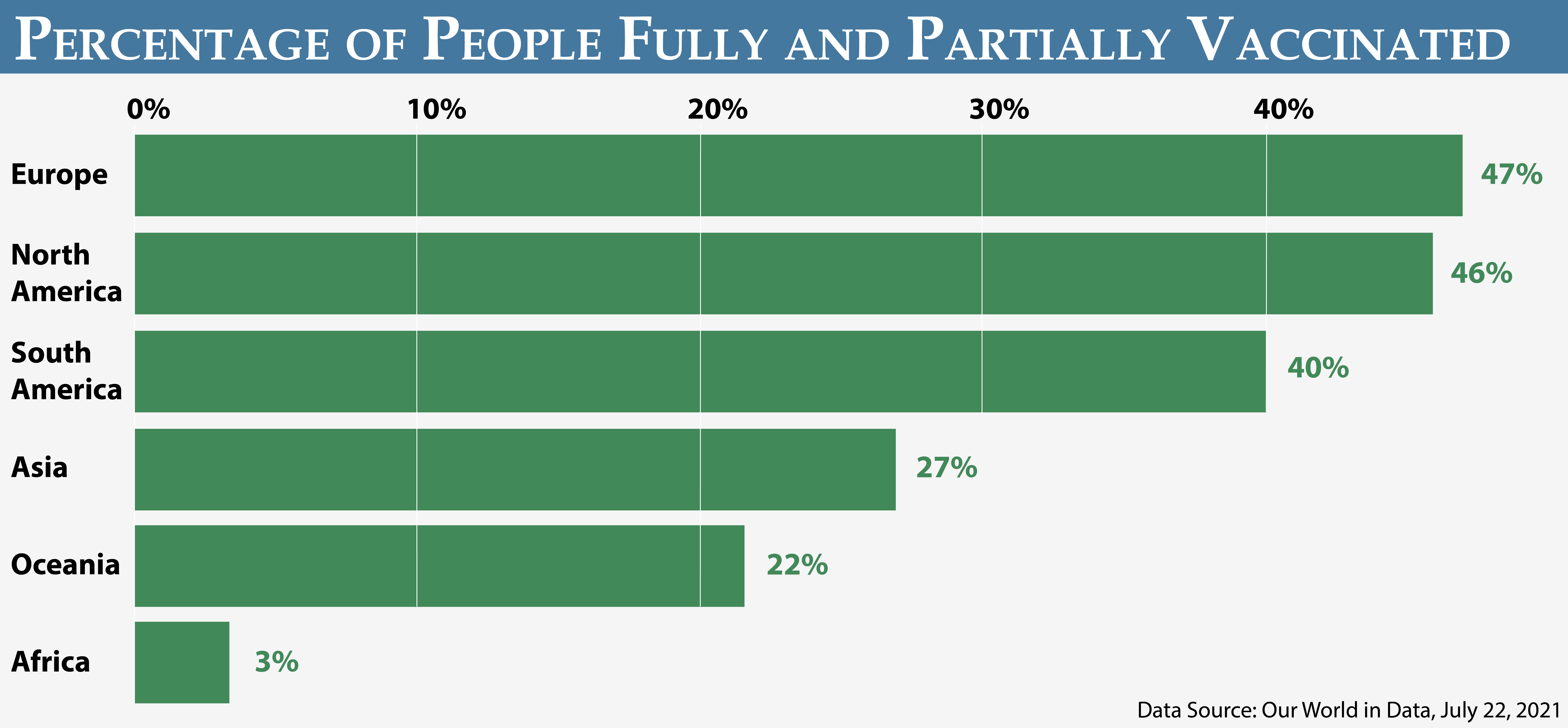

Africa remains, by far, the most vulnerable region in the world to the Delta COVID surge. Only 1.5 percent of Africa’s population has been fully vaccinated, and another 1.5 percent have received their first dose. The regions with the next lowest rate of vaccination are Oceania and Asia, with roughly a quarter of their populations being either fully or partially vaccinated. South America is at just under 50 percent. Roughly 1.5 percent of COVID vaccines administered globally have been in Africa, according to the WHO.

This huge disparity in COVID vaccine access persists despite the surplus availability of vaccines globally. It is estimated that the G-7 countries have purchased enough doses to cover their entire populations and still have more than 2.5 billion doses left over. Despite this surplus, vaccine shipments to Africa effectively ground to a halt just as the Delta surge was gaining momentum.

The pandemic’s spread in Africa has implications for the whole planet. If the virus continues to mutate in under-vaccinated regions, such as Africa, more transmissible and potentially more lethal and vaccine-resistant variants pose a risk for the entire global population. In Tanzania, for example, a variant has emerged with 34 known mutations, more than any other variant identified thus far. Addressing disparities in global vaccine access is not only imperative to limiting the devastating human costs in Africa but also for making headway in the broader battle to bring the pandemic under control.

Obstacles to Vaccine Access in Africa

Africa faces a critical vaccine shortage, paradoxically, while there is ample global supply. According to the One Campaign, “Rich countries are sitting on enough surplus doses to vaccinate all of Africa.” Four countries—the United States, Canada, Italy, and France—have already reached the tipping point where supply outpaces demand for COVID-19 vaccines. The United Kingdom is expected to reach this point by early August, and Japan and Germany are estimated to reach it by September.

Wealthy countries are likely holding on to a reserve of doses should there be a late demand from vaccine-hesitant populations, especially with the increase in cases from the Delta variant. Wealthy countries may also be preparing for the eventuality of vaccinating children under the age of 12. In the meantime, millions of doses could go to waste as they reach their expiration dates in the coming months. In the United States, for example, an estimated 26 million doses already allocated to the states are in excess of what are needed and could be immediately available for reallocation internationally, pending federal authorization.

Vaccines already distributed to U.S. states are especially valuable from an international perspective, as they’re ready to use immediately. “They’re real doses sitting on shelves and not waiting to be manufactured. That could change the game in terms of speed,” according to the ONE Campaign’s Jenny Ottenhoff. “Right now, the most important thing in terms of sharing doses internationally is sharing it fast.” Other wealthy countries are in similar positions.

By the end of 2021, vaccine makers are expected to have collectively manufactured about 10.9 billion doses of COVID vaccine. This is roughly sufficient to vaccinate all adults globally. Of these nearly 11 billion doses, 9.9 billion have already been purchased by wealthy countries as part of their effort to line up sufficient supplies for their populations. This leaves a relatively limited balance of 930 million doses of Chinese vaccines still available for purchase.

“Africa faces a critical vaccine shortage, paradoxically, while there is ample global supply.”

Even if wealthy countries aim to vaccinate 100 percent of their populations, there will still be 3 billion extra doses to share with countries that need vaccines. It is estimated that there will be 1.9 billion extra doses as soon as the end of August, more than enough to vaccinate Africa’s population of 1.37 billion.

For its part, the United States has committed to sharing 580 million doses internationally and has been the largest financial contributor to COVAX, the multilateral initiative established to facilitate vaccine access in low- and middle-income countries. The United States has also agreed to waive intellectual property protections on COVID vaccines and has not taken any actions to prevent export bans. The European Union has recently committed 200 million doses to COVAX yet continues to oppose waiving of intellectual property protections. China has donated 16.5 million doses to 66 countries but the 550 million doses it has agreed to supply to COVAX will solely be for purchase.

The bottom line remains that wealthy countries are controlling an excess supply of the life-saving vaccines while some parts of the world, especially Africa, are experiencing rapidly rising fatality rates.

COVAX and Private Sector Initiatives to Boost Access

African countries have largely relied on the COVAX Initiative for their vaccination planning strategies. COVAX was designed to coordinate global vaccine sharing with the recognition that many poorer countries would be unable to compete to purchase sufficient quantities of vaccine on their own. Over 90 countries, including 40 African countries, have been participating in the COVAX framework. African countries started ordering and paying for doses back in the first quarter of 2020. In total, the African Union and individual African countries have paid for 1.33 billion doses.

COVAX had initially promised to deliver 700 million vaccine doses to Africa by the end of 2021. However, so far less than 50 million doses have arrived through COVAX. The initiative largely stalled when India’s Serum Institute, COVAX’s core supplier, imposed an export ban on vaccines in March as India faced its own COVID surge. However, momentum may be shifting as the first delivery of doses donated by the United States are expected shortly. If additional doses become available, COVAX may yet be a significant contributor to improving vaccine access in Africa.

Private sector donations have stepped in to help fill the gap in the meantime. The Mastercard Foundation, in partnership with the African Union, negotiated a 220 million-dose deal to purchase single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccines for distribution across Africa from August to September. The deal includes an option to purchase an additional 180 million doses through 2022.

Distributional Challenges in Africa

Africa has considerable experience with mass vaccination campaigns, having achieved near-universal coverage for yellow fever and polio and recently confronted multiple Ebola outbreaks. Moreover, African countries have active community health worker structures down to the village level. This provides an established and trusted mechanism to effectively administer COVID vaccines as they become available.

COVID testing center in Madagascar. (Photo: UNICEF/Frank Dejongh)

Africa faces a series of practical logistical hurdles it must navigate, however. These include reassessing priority populations to receive vaccines with potentially short expiration dates, ensuring capacity for the ultra-cold chain infrastructure needed for some of the vaccines, securing funding and transportation to enable the vaccination campaigns to reach rural areas, and training health care workers in the peculiarities of administering each of the respective COVID vaccines that may be available.

As in other regions, African public health officials must also constantly educate their populations on the importance, safety, and efficacy of the COVID vaccines—a challenge made more complicated due to widespread misinformation and a lack of trust in government in some African countries.

Priority Actions Needed

Africa faces an unprecedented public health challenge in responding to the Delta surge and the circulation of other lethal variants. This has been made immeasurably more difficult due to the issue of inequitable vaccine access. Excess doses of COVID vaccine are available. They simply aren’t where they are needed most.

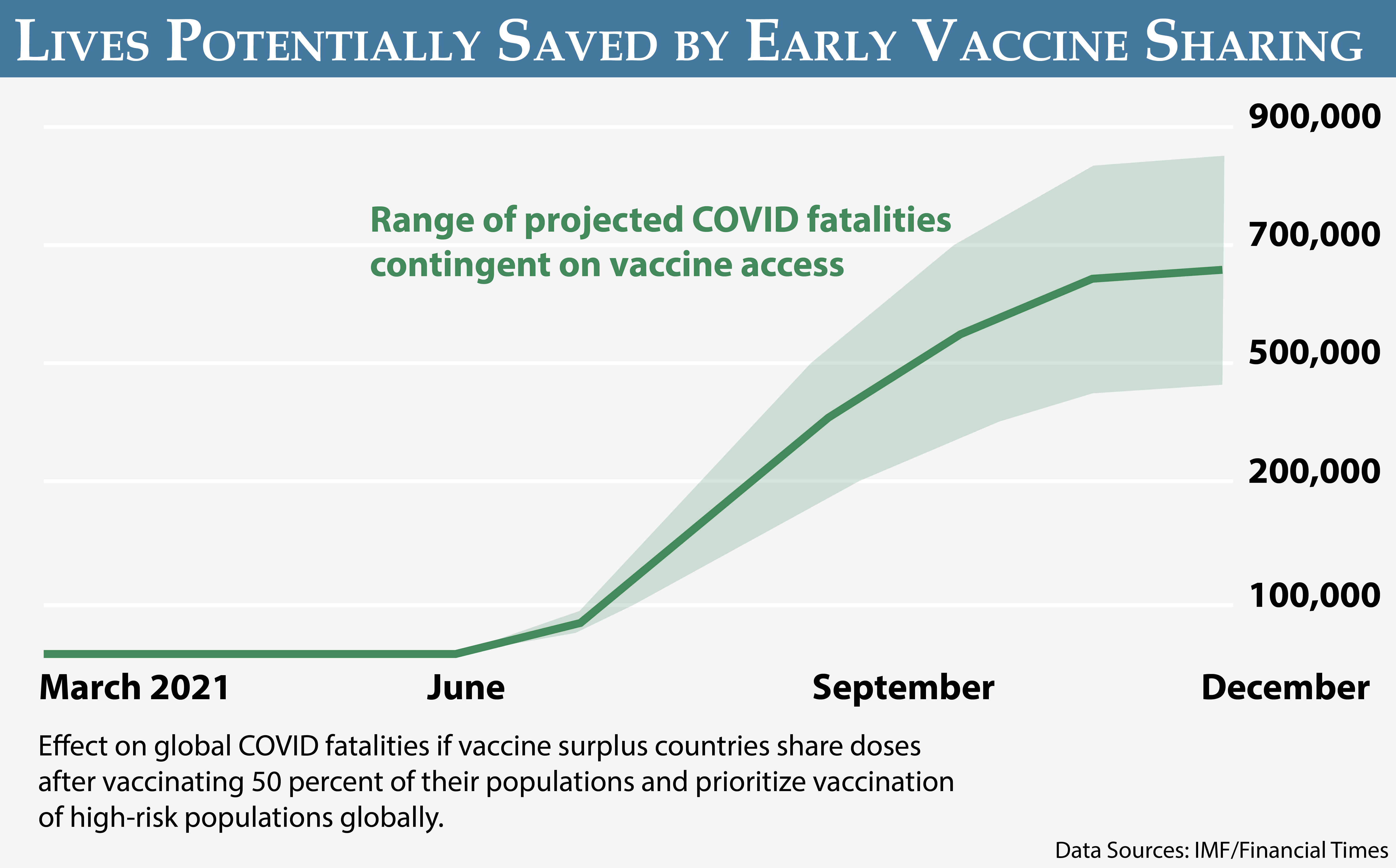

To respond to the urgency of the threat in the short term, wealthy countries need to authorize the release of currently available excess vaccine doses so these can be reallocated to countries currently facing a surge of COVID cases before these vaccines expire. Wealthy countries should also provide some portion of the 10.9 billion doses they have already purchased to countries currently in acute need. Africa is facing a surge in cases now—not at the end of 2021 or in 2022 when some schemes would have vaccination campaigns in Africa ramping up.

African countries should be at the top of this list of those receiving these doses as the continent is facing some of the highest fatality rates in the world. Given the gulf in disparity in vaccination rates between global regions, Africa should remain the priority for vaccine sharing until it reaches vaccination levels comparable to other regions. Six African countries—Uganda, Tunisia, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe—currently comprise over 80 percent of the recorded fatalities on the continent and should be prioritized. The situation remains highly dynamic from week to week, however, with two dozen African countries seeing rising case rates.

Health workers at the Mpilo Central Hospital’s Covid-19 Testing laboratory in Harare, Zimbabwe. (Photo: KB Mpofu/ILO)

African countries need to prime the pump for a successful vaccine rollout by prioritizing and preparing vulnerable populations, vaccination sites, and cold-storage facilities. Negotiating logistical challenges, training health care workers, and conducting ongoing public education campaigns are all priorities prior to the arrival of vaccines in significant quantities. Additionally, public health officials should increase COVID testing to better target limited vaccine doses as they become available.

Finally, investments in Africa’s vaccine manufacturing capability will help address ongoing supply challenges in the medium term. The WHO is setting up a vaccine production hub in South Africa to produce COVID-19 vaccines with mRNA technology. The African Union and the Africa Center for Disease Control and Prevention, through the Partnership for African Vaccine Manufacturing, have simultaneously launched an initiative to create five regional research and vaccine hubs on the continent.

Having multiple production facilities based on the continent would increase diversity in supply chains, reducing Africa’s reliance on a single production facility based outside the continent. Local production capacity would furthermore reduce costs of vaccine importation and cold chain. It would also be an investment in the future. The market for other vaccine production, including a universal pan-coronavirus vaccine and HIV, is substantial over the next 10 years.

Additional Resources

- ONE Campaign, “Data Dive: The Astoundingly Unequal Vaccine Rollout,” accessed July 22, 2021.

- Olivia Goldhill, “States Are Sitting on Millions of Surplus COVID-19 Vaccine Doses as Expiration Dates Approach,” STAT, July 20, 2021.

- Lori Hinnant, Maria Cheng, and Aniruddha Ghosal, “Vaccine Inequity: Inside the Cutthroat Race to Secure Doses,” AP, July 18, 2021.

- Abdi Latif Dahir and Josh Holder, “Africa’s Covid Crisis Deepens, but Vaccines Are Still Far Off,” New York Times, July 16, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Devastating Human Toll as the Delta Variant Takes Hold in Africa,” Spotlight, July 9, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Lessons for Africa from India’s Deadly COVID Surge,” Spotlight, May 28, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Dispelling COVID Vaccine Myths in Africa,” Spotlight, May 21, 2021.

More on: COVID-19 Health & Security