Joseph Kabila. Photo: European Parliament.

This article is the first in a series that analyzes the ongoing challenges to the democratic process in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and how various actors and institutions will shape the outcome.

Part 1: A Looming Calamity in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Part 2: The DRC’s Oversight Institutions: How Independent?

Part 3: The Role of Civil Society in Averting Instability in the DRC

Part 4: Security Sector Institutions and the DRC’s Political Crisis

Part 5: The Role of External Actors in the DRC Crisis

* * *

President Joseph Kabila was to have fulfilled his second five-year term on December 19, but he stayed on as a result of a series of legal, political, and constitutional maneuvers to keep him in power. This has plunged the Democratic Republic of the Congo into one of its worst political crises since the end of its two devastating civil wars. Constitutionally, it will be time for a democratically elected successor to take his place. The United Nations, African Union, European Union, France, United Kingdom, and United States all pushed to hold elections as scheduled, but Kabila has avoided organizing them and instead seems intent on holding onto power indefinitely.

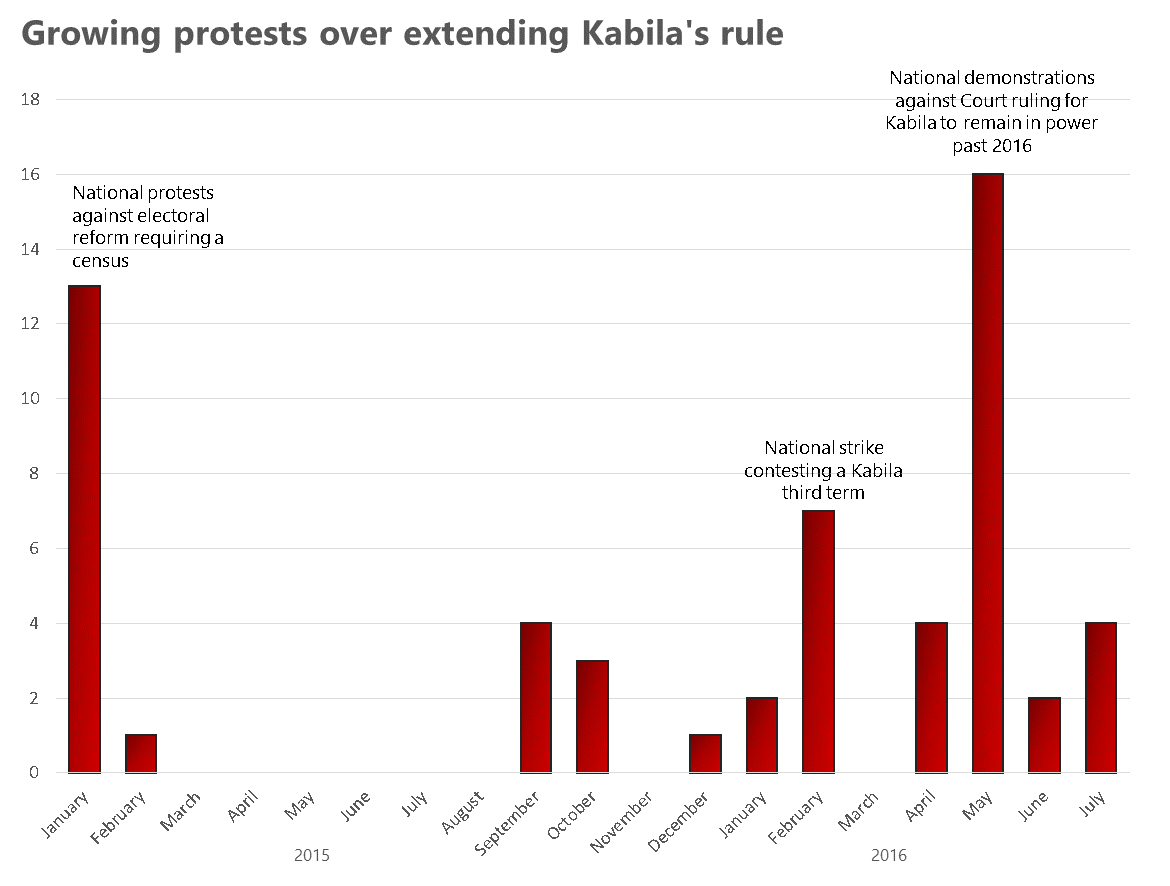

Throughout the crisis, the Congolese people have actively demonstrated to secure their right to elect a new head of state (see chart). These protests have at times been met by violence by security forces resulting in dozens of deaths and disappearances. Media outlets have been closed. Opposition candidates, journalists, and human rights advocates continue to face harassment, abuse, and unlawful detention. Kabila, moreover, has attempted to avert his departure by eroding the country’s legal checks and balances and denying the opposition from any platform from which they could challenge his authority.

In short, a collision of visions for the country looms. The resulting instability could drive Africa’s second largest country, often referred to as the heart of Africa, into a devastating conflict and regional war. Memories of the 1997–2003 conflict known as “Africa’s First World War,” remain fresh. Ongoing armed conflict and systematic sexual violence have persisted in the east of the country ever since.

Poor Governance, Unrealized Potential

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is one of the world’s largest, richest, and most impoverished countries all at once. It covers 2.3 million square kilometers of Central Africa (roughly a quarter the size of the United States) and hosts lush rainforests, enormous deposits of copper, gold, and diamonds, and 50 percent of the world’s cobalt. The population of 80 million people will balloon to 100 million in just 10 years. Yet out of 188 countries, the DRC ranks 176th in human development. Its GDP per capita is only $783—a calamitous 63 percent drop since the country achieved independence in 1960.

Poor political leadership and a subsequent dearth of accountable institutions have prevented the country’s resource wealth from ever benefiting its people. Ruled for 32 years by Mobutu Sese Seko, the DRC (then known as Zaire) is famous for its limited infrastructure despite its immense size and population. Mobutu is widely believed to have embezzled at least $4 billion from state coffers over the course of his rule, setting the tone for government predation of public resources. He also restricted investments in education and roads that could have facilitated organized opposition to his rule. To this day, the DRC remains a highly fragmented country lacking a shared national identity or strong connection to Kinshasa.

DRC at a Glance

| Measure | DRC | Sub-Saharan Africa |

|---|---|---|

| Under-five mortality rate (per 1,000 live births) |

98 | 83 |

| Access to safe water (%) | 52 | 67 |

| Mobile subscriptions (%) | 54 | 71 |

| Internet users (%) | 3 | 19 |

In 1996, Mobutu, ailing and nearing the end of his life, ignored the fissures in the state as militants far in the east launched cross-border attacks from neighboring Rwanda. The result was the First Congo War, where Rwanda and Uganda invaded and with their partisans ultimately overthrew Mobutu’s regime and installed Laurent Kabila as president in 1997. By the next year, Kabila’s lack of legitimacy, persistent kleptocracy, a plethora of militias, and angst from neighboring countries over Rwanda’s outsized influence in Kinshasa had set off a second, brutal, and devastating conflict that lasted until 2003. Epidemiological reports suggest the fighting and instability may have resulted in 5.4 million direct and indirect deaths.

Known as “Africa’s First World War,” at least 13 countries became involved in the conflict in one way or another. Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, and South Africa on one side, (the latter non-militarily). Angola, the Central African Republic, Chad, Libya, Namibia, the Republic of the Congo, Sudan, and Zimbabwe on the other. The rationales for involvement echoed World War I. Complex alliances, regional rivalries, and control of the DRC’s vast resources spurred countries to join the battle or support proxies. At times, the DRC served only as the battleground between other states, yet its citizens bore the brunt of the killing. The pillaging and instability caused by invading armies and rebel groups have continued in some form ever since.

Joseph Kabila first came to power in 2001, following the assassination of his father. The younger Kabila was elected (in the second round of voting) under a new constitutional framework in 2006—the DRC’s first elected president in more than 40 years. Kabila stood for reelection in 2011, facing 10 other candidates. Amid reports of significant irregularities, he was declared the winner with less than 50 percent of the vote. (A constitutional amendment in January 2011 had eliminated the second round of voting). Concerns that Kabila is now further eroding the country’s already weak democratic institutions in an effort to maintain power have raised tensions surrounding the 2016 electoral process, with far-reaching consequences for Congolese citizens and indeed the whole region.

Using All Means Available to Maintain Power

Kabila has sought to extend his rule through four primary methods.

First, in early 2015, Kabila insisted that a long-stalled decentralization plan had to be implemented prior to a presidential election. Doubling the number of provinces from 11 to 26, the new arrangements would require expensive and complicated local elections to be held across the DRC, monopolizing the capacity of the state’s electoral institutions.

Second, Kabila has weakened and coopted oversight institutions. This has provided Kabila more legitimacy in his actions. For example, the Kabila-friendly Constitutional Court agreed that local elections must take place before presidential ones, and that Kabila could rule until whenever such elections may occur. At the same time, the electoral commission noted that bureaucratic processes like reviewing voter lists would make a presidential election logistically impossible in 2016. The electoral commission’s Vice President, meanwhile, was reportedly pressured into resigning.

Moïse Katumbi

Third, Kabila has been removing potential electoral competitors one by one. Prominent opponent and former governor of Katanga Province, Moïse Katumbi, was sentenced in absentia in June 2016 on what were seen as politically motivated charges. He was later refused entry to the country when he tried to return. Another opposition candidate, Martin Fayulu, was arrested in advance of pro-election demonstrations. For now, longtime democratic stalwart, Étienne Tshisekedi, who has recently returned to the DRC, remains free.

Finally, some members of Kabila’s party have called for a constitutional referendum to eliminate presidential term limits. Such moves mirror similar actions by other African strongmen to extend their time in office—including in Burundi, Rwanda, and the Republic of the Congo in the last year. In Burkina Faso and Burundi, referenda on term limits resulted in a coup and a civil war, respectively. Indeed, efforts by African leaders to extend their time in office indefinitely leave citizens few legal avenues through which to challenge them. Peaceful protestors in the DRC have likewise indicated that they may need to resort to force if Kabila does not step down as legally required.

By systematically undermining options for popular participation in the political process, Kabila has further weakened the country’s already fragile political institutions and their checks and balances. He seems to have calculated that the opposition is too weak to stop him and that the international community is unlikely to meaningfully intervene. Experience in the DRC has shown, however, that once unleashed, instability can take on a life of its own with devastating effects for the country and the region.

The Challenges to Change Course

The challenge facing Congolese citizens and regional and international partners is how to navigate the current crisis away from such an outcome. More strategically, the challenge facing reformers is how to establish a government that is more accountable to its citizens and harness the country’s vast mineral wealth in order to create a path for sustainable development. In addition to the political actors, the DRC’s fledgling democratic institutions, security sector, civil society, and media will all have central roles in shaping this outcome.

Overcoming Kabila’s intransigence and strengthening the DRC’s democratic institutions would also send a message to other African leaders who are inclined to extend their tenure in power. Reinforcing the importance of constitutional term limits and democratic norms, in turn, would advance a vision for the continent that African citizens widely favor.

Africa Center Experts

- Raymond Gilpin, Dean of Academic Affairs

- Dorina Bekoe, Associate Professor, Conflict Mitigation, Prevention, and Resolution

- Joseph Siegle, Director of Research

Additional Resources

- Jason Stearns, “Congo: Une bataille électorale périlleuse,” Rapport d’analyse 1, Groupe d’etude sur le Congo, Aoút 2016.

- Dorina Bekoe, “Africa’s Electoral Landscape: Concerning Signals, Reassuring Trends,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 16, 2016.

- Gérard Prunier, “Why the Congo Matters,” Issue Brief, Atlantic Council, March 14, 2016.

- Raymond Gilpin, “Prospects for Peace in the DRC and Great Lakes Region,” testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, February 28, 2014.

- Rigobert Minani Bihuzo, “Unfinished Business: A Framework for Peace in the Great Lakes,” Africa Security Brief, No. 21, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 2012.

More on: Democratization Democratic Republic of the Congo