English | Français

A morning briefing for trainee officers at the General Dhagabadan Training Centre in Mogadishu. (Photo: AFP/Amaury Falt-Brown)

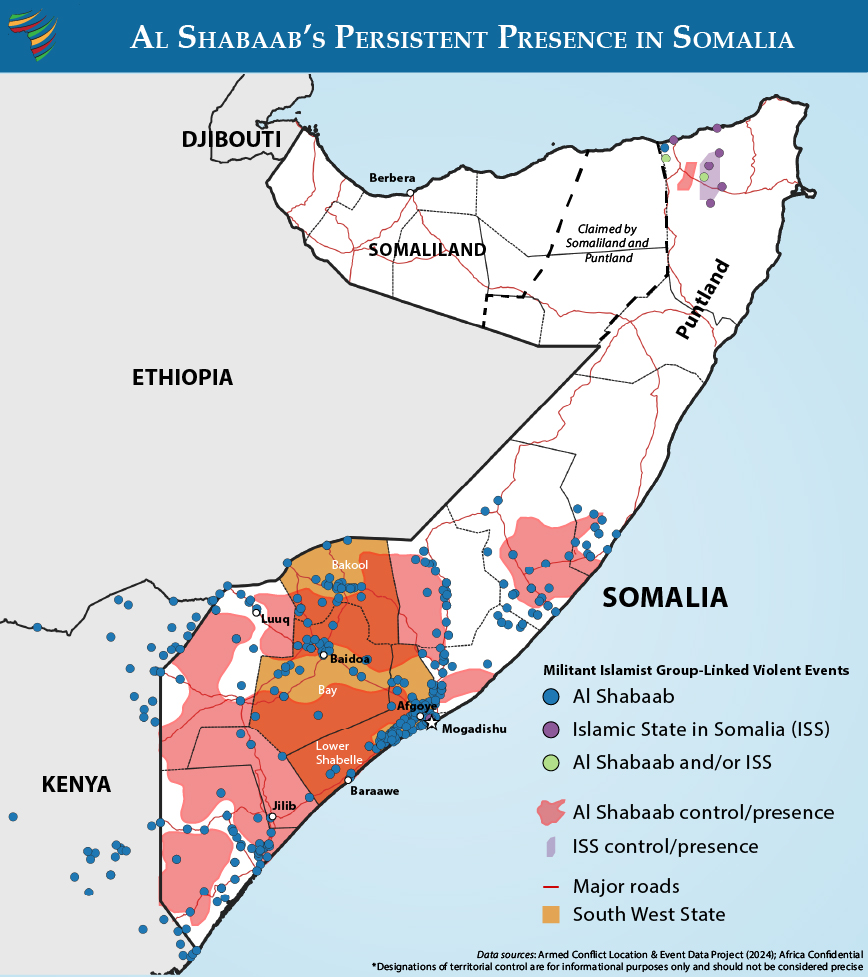

Offensives in recent years by the Somali National Army (SNA), supported by local militias, have delivered substantial territorial gains for the government in its battle with al Shabaab. Yet, the militant Islamist group remains a potent force and has regularly proved its capability to reverse some of these gains and reach into areas ostensibly under government control. This pattern of progress and setback continues to prevail across parts of Somalia, resulting in a constantly shifting patchwork of territories controlled by the government. In the past year alone, Somalia experienced nearly 4,500 fatalities linked to militant Islamist violence.

While substantial efforts have been made to stabilize and hold recovered communities under various frameworks and policies, little progress has been realized toward longer term development and consolidation. Hard-earned military gains remain tenuous and the process of restricting al Shabaab’s area of operations has been slowed. While resource constraints are always a consideration and continue to be significant, the lack of pre- and post-operation coordination between military and civilian authorities is perhaps a more important constraining factor for stabilization efforts in Somalia—and countering al Shabaab at the strategic level.

Hard-earned military gains remain tenuous and the process of restricting al Shabaab’s area of operations has been slowed.

The situation in South West State, home to over 4 million of Somalia’s 18 million citizens, is illustrative. Despite numerous clashes and battlefield successes by government forces, most of South West State remains directly or indirectly under the control of al Shabaab. The militant group controls four full districts, amounting to one-third of the territory, and influences much more, particularly in the rural areas and along the main roads from Mogadishu to Baidoa to Luuq and from Mogadishu to Afgoye to Baraawe. The government controls several population centers though often not the territory between, which makes access and movement between these difficult and limits the reach of the government.

This persistent insecurity inhibits the return of internally displaced populations, the provision of services, commerce, investment, and job creation that can sustainably stabilize these territories.

The gaps between the “clear” and “hold” stages of the stabilization continuum in Somalia are often linked to a lack of understanding of the tasks involved and inadequate coordination between military and civilian authorities. Strengthening these connections is a vital element in the effort to consolidate Somalia’s gains in its fight against al Shabaab.

Many Stakeholders to Coordinate

South West State hosts Somali security contingents from the 60th Division and other brigades of the SNA, units of the federal Somali National Police (SNP), and forces from the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA). As a Federal Member State (FMS) within Somalia’s federal system, South West State also has its Darwish force, the South West State Special Police Force (SWSPF).

Coordination is complex with a multitude of military and civilian actors and activities.

South West State also hosts security force contingents from Uganda and Ethiopia under the African Union Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM) as well as the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) under national command deployed under a bilateral arrangement between Ethiopia and Somalia. The transition from the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) to AUSSOM has also involved the handover of 16 ATMIS bases to Somali control.

Stabilization strategy is covered by national and state policies, including the South West State Stabilization Plan, the Operation Gobanimo Stabilization Plan, the National Stabilization Strategy (NSS), and the Revised Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) Stabilization Plan – State Revival/Early Recovery Programme. The last envisages a whole-of-government approach, which in South West State, includes the South West State Office of President, the Ministry of Interior, Local Governments and Reconciliation (MOILGR), the Ministry of Internal Security (MOIS), the Ministry of Justice and Judiciary (MOJ), the Ministry of Energy and Water Resources (MOEWR), the Ministry of Health and Human Services (MOH), the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Higher Education (MOE), the Ministry of Endowments and Religious Affairs (MOERA), the Ministry of Information and Social Awareness (MOISA), the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management (MOHADM), the SNA and the Somalia Disaster Management Agency (SODMA).

The NSS provides a conceptual framework for stabilization, identifying four main areas:

- Community Recovery

- Social Reconciliation and Cohesion

- Local Governance

- Rule of Law

Stabilization is portrayed as taking place along a continuum from pre-recovery to recovery to development. Recovery is envisaged to take up to 9 months, with an early recovery phase of 0-90 days and a consolidation phase of 6-9 months. Early recovery includes the supply of food and other items to address vital basic community needs, along with initial dialogue to support social cohesion and local reconciliation. Consolidation activities include the establishment of district authorities and the rehabilitation of infrastructure along with health, education, and livelihoods.

Coordination is complex with this multitude of military and civilian actors and activities. Within South West State, the Minister of MOILGR chairs a state stabilization coordination meeting which meets quarterly. It is attended by state-level ministers, representatives from the federal Ministry of Interior, Federal Affairs and Reconciliation (MOIFAR), international partners, and civil society. There is also a regional security council that meets monthly, chaired by the state president. Coordination is therefore limited to infrequent meetings at a senior level (ministerial/director general). Technical or working-level teams from the relevant ministries and security forces typically do not meet, share information, or plan together.

Limited Understanding and Challenges of Operationalizing Roles and Responsibilities

In addition to infrequent meetings and insufficient detail, joint stabilization planning is hampered by unfamiliarity between military and civilian actors and, indeed, between different civilian actors. This has constrained operational coordination at several levels.

First, there is a lack of understanding of the military tasks in stabilization operations. The primary task of establishing a safe and secure environment with freedom of movement is well recognized. But the secondary, though equally important, military task of helping to restore public security, rule of law (ROL), basic services and infrastructure, humanitarian assistance, livelihoods, and longer-term governance is not.

The military, in taking over an area, has responsibility for the civilian population until such responsibility is handed over to appropriate authorities.

Deriving from obligations under International Humanitarian Law (specifically, the 4th Geneva Convention), the military, in taking over an area, has responsibility for the civilian population until such responsibility is handed over to appropriate authorities. Such a transfer of civil administration should not be delayed as the military has limited competence in these functions and will quickly lose their legitimacy to exercise such responsibilities. There is also a risk of “militarizing the humanitarian space” with negative implications for civilian agencies. It is vital, therefore, that military commanders and planners understand that stabilization is more than security and requires revitalizing communities, livelihoods, markets, schools, clinics, justice, and administration.

Second, there is a limited understanding of the varying timescales and information required by different actors for the mobilization of resources and the delivery of assistance and services. The military can launch operations in days with forces that are already trained, equipped, and supplied. Some civilian actors can respond as quickly with emergency stocks. However, most civilian actors require longer notice to build capacity and infrastructure and train staff, particularly if they also must obtain funding and supplies.

This raises the problem of how to coordinate across such a disparity, cognizant of the military requirement for operational security of future plans. The MOILGR and MOIS have identified the need for “deployable capabilities” of police, administrators, and judges, to provide a rapid, though temporary, response for governance and ROL until a permanent provision can be made. This underscores the importance of government organizations developing the operational capacity for stabilization by hiring and developing staff, organizing them, and deploying them.

An ATMIS patrol. (Photo: Atmis Somalia)

Other civilian actors have stressed the need to have the flexibility of resources that could provide adaptable responses to match changes in the operational situation, such as agreed funding for infrastructure and training or stocks of equipment and supplies. It is necessary that all actors involved in stabilization have sufficient mutual understanding and visibility of the capabilities, resources, and constraints of others. This builds trust between partners and allows alignment of activities.

Third, there is no comprehensive whole-of-government campaign framework that links overall aims (policies) to achievable tactical objectives and available resources (plan). Few actors can identify what might be possible to advance the next set of objectives or operations. The gap between the federal/strategic level and state/tactical level is absolute.

The requirement to establish effective civil administration means that insecurity must be reduced to a level that fosters civilian life and enables the provision of essential services.

Fourth, information, decision making, and control are often highly centralized and delegation of these functions is extremely limited. Interagency contact is therefore restricted to heads of organizations or departments. This constrains state stabilization coordination to quarterly meetings at the senior level. Even if staff at the working level meet weekly, they would likely have little authority or capability to share information and take decisions.

Fifth, there is a difference in understanding between military and civilian actors over what might be regarded as secure or not. The military tolerance for risk is understandably higher, but the requirement to establish effective civil administration means that insecurity must be reduced to a level that fosters civilian life and enables the provision of essential services. This also applies to the local population, who must consider making their life and home in their community regardless of which administration or force is present. Accordingly, such security must be proven effective and long term. The impact of recent reversals of government gains in central Somalia by al Shabaab may be local but it sends a signal to other communities nationally who question if security provision from the government will be equally impermanent.

Operationalizing Stabilization Best Practices

To address these shortcomings and to improve stabilization operations in Somalia, the following priority actions are recommended.

Promote stabilization doctrine that identifies all the military tasks in stabilization. This doctrine must include both the primary actions (to establish a safe and secure environment and freedom of movement) and the secondary (to assist the restoration of governance, ROL, basic services and infrastructure, humanitarian assistance, livelihoods, and community).

Build trust and common understanding between all stabilization actors. A dedicated effort to gain a greater comprehension of each institution’s roles, capabilities, resources, and constraints is needed. This includes aligning the varying timescales and information required by different actors for the mobilization of resources and the delivery of assistance and services.

Somali children welcoming the Ugandan and Somali troops in Afgoye, Somalia. (Photo: AFP/Noe Falk Nielsen/NurPhoto)

Enhance coordination. Increasing the frequency of state stabilization coordination meetings from quarterly to monthly, for example, will strengthen the familiarity of information needs of each partner and make these meetings more operationally relevant. Establishing formal routines for information exchange and collaborative work will enable regular weekly meetings for technical teams to undertake joint operational planning and share information.

Increase delegation to enable interagency coordination and joint planning. This will require significant cultural adaptations to enable and empower local authorities and ensure local coordination is informed and effective. This shift will necessitate improved vertical information management and distribution processes within each organization. The current top-down, centralized management of activity and resources impedes timely coordination and planning.

Develop comprehensive whole-of-government campaign plans. Stabilization strategies linked to overall aims need to focus on realistic tactical objectives within available resources. They also need to address all phases of stabilization (clear and hold, early recovery, and consolidation). This planning needs to avoid over-extension, which has resulted in stalled stabilization and reversals in security. Limitations on capabilities and resources will place an emphasis on smaller, achievable objectives in the short term. Planning will also need to recognize and innovate to address stabilization shortfalls in secure recovered areas.

Increase the speed and adaptability of civilian response. Identification of the skillsets, personnel, and resources needed to establish a functioning government that can provide basic services is an essential (and often missing) step in the stabilization process. This process of identification can guide the requisite training, mobilization of personnel, and preparation of deployable interim capabilities, stockpiles, and resources. This will facilitate more timely and effective deployments to better secure the hold, early recovery, and consolidation stages of stabilization operations.

Ronnie Bradford is an advisor with GIST Research and has worked with security actors in Somalia and Somaliland for over a decade. He is a retired Colonel from the British Army. This analysis draws from exchanges with representatives from the South West State’s Ministry of Interior and Local Governments and Reconciliation (MOILGR), the Ministry of Internal Security (MOIS), the Somali National Army (SNA), and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Additional Resources

- Hiraal Institute, “Escalation and Adaptation: Assessing President Hassan Sheikh’s War on Al-Shabaab,” May 2024.

- Daisy Muibu, “Somalia’s Stalled Offensive against al-Shabaab: Taking Stock of Obstacles,” CTC Sentinel 17, no. 2 (February, 2024).

- Wendy Williams, “Reclaiming Al Shabaab’s Revenue,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 27, 2023.

- International Crisis Group, “Sustaining Gains in Somalia’s Offensive against Al-Shabaab,” Briefing No. 187, March 21, 2023.

- Samira Gaid, “The 2022 Somali Offensive Against al-Shabaab: Making Enduring Gains Will Require Learning from Previous Failures,” CTC Sentinel 15, no. 11 (November/December 2022).

- Helmoed Heitman, “Optimizing Africa’s Security Force Structures,” Africa Security Brief 13, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2011.