An M23 fighter stands by coltan mining pits in Rubaya, DRC. (Photo: AFP/Camille Laffont)

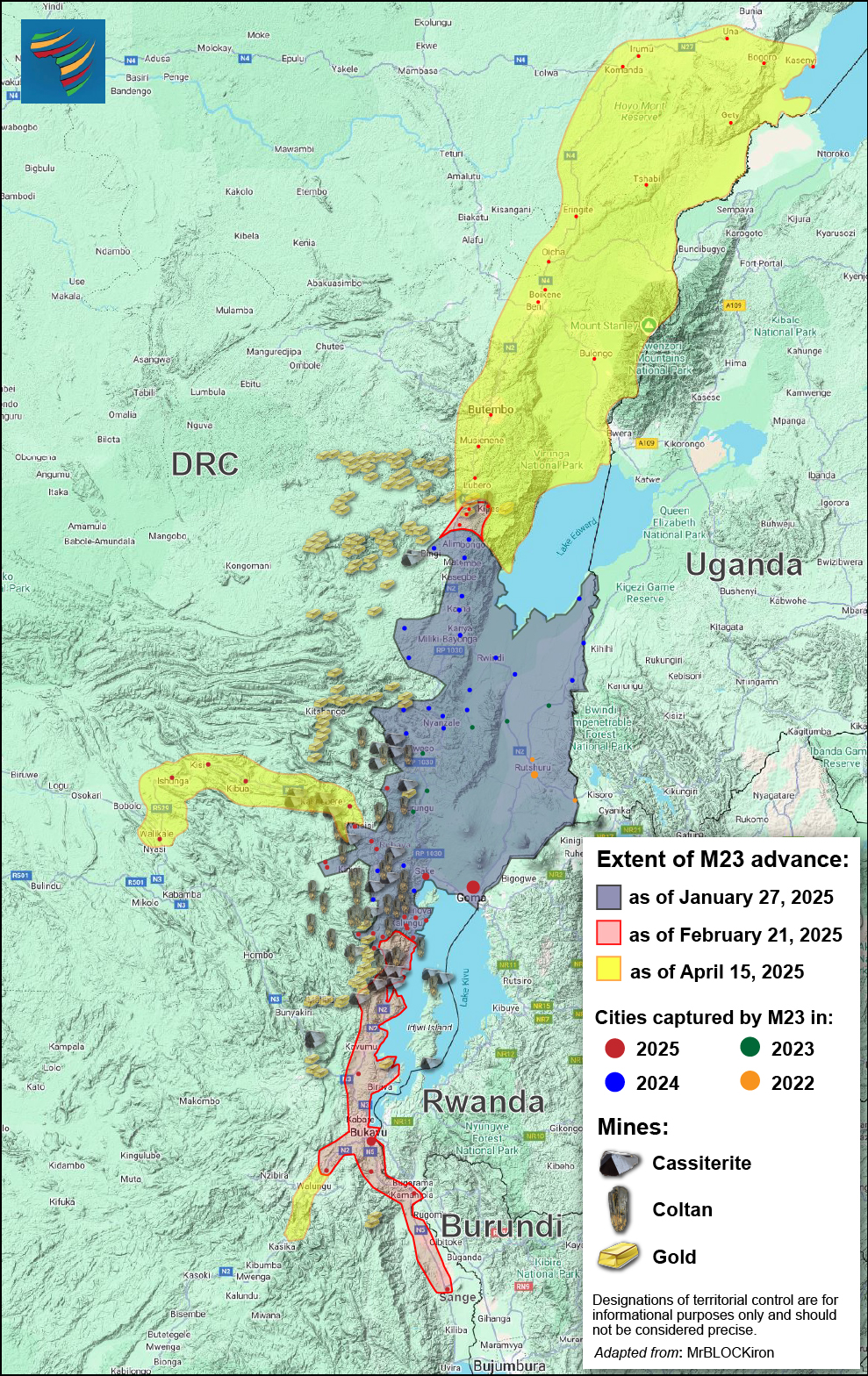

More than 1.1 million people have been displaced as a result of M23’s latest rebel offensive in the eastern Democratic of the Congo (DRC) that began in December 2024. An estimated 7,000 people—mostly civilians—are believed to have been killed. Hospitals remain overwhelmed with casualties and people continue to flee to neighboring countries and the Congolese interior. The rapid advance of the Rwandan-backed M23 militia and its political coalition, the Alliance Fleuve Congo (AFC), has sparked fears that the country could be carved into zones of influence and annexed. Insurgent forces currently control sizable territories on 4 fronts in the eastern DRC:

- North of the provincial capital of North Kivu, Goma

- South of the provincial capital of South Kivu, Bukavu

- West of Goma in Walikale and surrounding territories

- North of Lake Edward extending along the Uganda border to Lake Albert

In total, M23 controls territory roughly 8 times the size of Belgium. Should they continue to advance to neighboring Tshopo and Kisangani provinces, the rebellion will control an area approximately the size of Germany.

Uganda has simultaneously deployed forces into the Congo under an agreement with the DRC government to combat a separate threat from the violent criminal group, the Allied Democratic Forces, which operates on the Uganda-DRC border. Uganda’s role remains ambiguous, however, as further deployments of the Uganda Peoples Defense Forces into Ituri Province to combat another criminal network, the Coopérative pour le développement du Congo (CODECO), occurred nearly in tandem with M23 advances farther south. Notably, Uganda has a long history of cooperation with Rwanda on previous military interventions in the DRC.

The ongoing presence in the eastern DRC of the Forces Démocratique de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR), the remnants of the forces implicated in genocide in Rwanda in 1994, continues to be a major source of tension between the DRC and Rwanda.

The significant role of foreign countries in the DRC has also stoked concerns of a regional conflagration harkening back to the First and Second Congo Wars, where at least 8 African militaries deployed forces in support of opposing sides.

The multidimensionality of the DRC crisis makes it particularly challenging to resolve.

In addition to these regional dimensions, the contested nationality and citizenship for Congolese of Rwandan and Burundian descent in eastern Congo is a major grievance that has fueled all major rebellions in the DRC.

Equally contentious and emotive is the issue of how the Congo’s vast natural resources and mineral wealth should be managed. They remain a source of conflict and competition among dozens of armed militias as well as neighboring countries.

The weak legitimacy and capacity of the DRC government, and its tenuous control of territories outside the capital of Kinshasa, has made it increasingly vulnerable to rebellions and anti-government sentiment. Controversial electoral victories by President Félix Tshisekedi in 2019 and 2024 as well as an attempt by his ruling coalition to amend the Constitution to pave a path for a third term, have further eroded popular support for the government.

DRC Republican Guard soldiers in the streets of Kinshasa.

The 150,000-strong Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) has been hobbled by indiscipline, parallel chains of command, erratic pay, and predatory behavior. This ineffectiveness has facilitated the rebel offensive. To compensate for these weaknesses, the Tshisekedi government has turned to a collection of militias called Wazalendo and Eastern European mercenaries, though they have not stemmed the rebel advances. Some militias, police, and FARDC units have reportedly joined the rebellion.

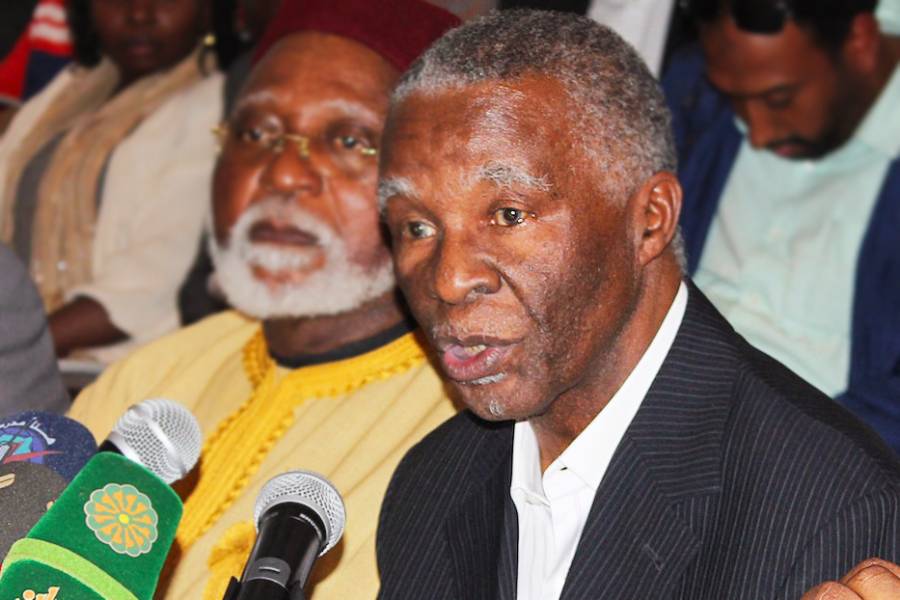

This complexity mirrors previous DRC conflicts. Of particular relevance is the Inter Congolese Dialogue (ICD) and resultant Sun City (South Africa) Accords that ended the Second Congo War (1998-2003). This conflict demonstrated similar root causes, actors, and external dimensions to the current crisis. Former South African President Thabo Mbeki, a key architect of those talks, has noted that the current conflict does not present anything fundamentally new in terms of core issues. Reviewing lessons from the ICD, therefore, may provide guidance for deterring a further escalation of the current DRC crisis.

Relevant Modalities from the Inter Congolese Dialogue

Former South African President Thabo Mbeki. (Photo: AFP)

The African Union’s (AU) latest DRC peace initiative involves the fusing of the Luanda and Nairobi processes led by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and East African Community (EAC), respectively. It comprises a panel of five former presidents from Central, South, and East Africa: Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya, Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria, Kgalema Motlanthe of South Africa, Sahle-Work Zewde of Ethiopia, and Central African Republic’s Catherine Samba-Panza. The AU nominated Togolese President Faure Gnassingbe to coordinate the process.

The African mediators face two immediate challenges. First, is to assert ownership of the DRC peace initiative by giving it adequate financial and technical resources, while discouraging the parties from “forum shopping.” Second, is to initiate an inclusive Congolese process that finds a comprehensive solution to the internal and external dimensions of the crisis.

The Second Congo War was settled by the ICD, which was mediated by the late Botswana President, Ketumile Masire, with the support of President Mbeki. Many signatories of the ICD remain engaged in the political process. Numerous regional diplomats and international guarantors that shaped the Dialogue are likewise actively seeking solutions to the current crisis.

The Context

The Second Congo War involved an offensive by three rebel groups backed by Uganda and Rwanda to topple the government of the late DRC President, Laurent Kabila. He was supported militarily by Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe. This is relevant to the current crisis as SADC deployed troops from Malawi, South Africa, and Tanzania to support DRC’s counteroffensive against M23. SADC decided to withdraw its forces in late February to focus on diplomatic solutions for reaching a ceasefire.

Representatives from SADC and the Zambian and South African militaries at the signing ceremony for the ceasefire between M23 and the SADC Mission in the DRC. (Photo: AFP/Jospin Mwisha)

The merging of the SADC and the EAC peace initiatives follows a similar tact taken during the Second Congo War. The merger of peace processes by the two regional bodies at that time paved the way for the 1999 Lusaka Peace Accord—a ceasefire by all foreign forces that resolved the external dimension of the crisis. Mediated with strong South African engagement, first by Nelson Mandela and then Thabo Mbeki, the 1999 Lusaka Peace Accord ended hostilities between six African countries. It facilitated the withdrawal of their militaries, set up a ceasefire monitoring commission, and helped create additional agreements, such as the 2002 Pretoria Accord between the DRC and Rwanda, as well as a separate agreement between Uganda and Angola that led to the creation of the 2003 Ituri Pacification Accord. The Lusaka Peace Accord also created the political conditions for the success of the ICD.

The Process

The ICD shifted the momentum away from the military protagonists towards a strategic initiative involving Congolese civilian stakeholders.

The ICD developed through several stages: a Declaration of Fundamental Principles by all the armed groups under pressure from their regional backers signed in May 2001 in Lusaka, Zambia. This was followed by a larger meeting of Congolese stakeholders in Abuja, Nigeria and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in September and October, respectively. The participants agreed that the ICD should consist of five components: government, armed opposition, unarmed opposition, civil society in government and rebel-controlled areas, and the “Forces Vives” or “Vital Forces” who represented influential professional organizations and personalities. These components chose their teams and proceeded to Sun City to begin negotiations. The inclusive nature of this process is highly relevant for the current context as any agreement will need to enjoy broad national participation and ownership to accommodate the diverse constituencies comprising Congolese society.

Issues under Contention

The Sun City Accords covered 36 articles related to problems that had bedeviled Congo since independence. Key thematic pillars included:

- Political liberalization

- Free movement of people, goods, and services

- Management of mineral resources

- Security sector reform

- Foreign forces including mercenaries

- Disarmament of non-state actors

- Vetting and recruitment into the security services

- Territorial unity

- Nationality and citizenship

- Protection of minorities

Relevant Articles Emerging from the ICD Process

Article 3

- Enacted guardrails to ensure that Congo is governed as a democratic state. It also explicitly outlawed the accession to power through armed rebellion or military coup.

Article 5

- Outlawed the practice of trying civilians in military courts, reorganized the system of military justice, and established an independent review process to address crimes committed by military forces against civilians.

Article 13

- Created an independent mechanism to oversee the recruitment of individuals into the national military, ensure that recruitment patterns reflected the national composition of population groups, and outlaw the recruitment of child soldiers.

Article 14

- Established a system to integrate former government forces and ex-rebel organizations into a new national military.

Article 15

- Put into place a system of sanctions against individuals, groups, or parties that violate provisions of the Sun City Accords, its institutions, and the spirit of agreed resolutions. This Article also created an independent body empowered by the Constitution to oversee the implementation of the Accords.

The issues of territorial unity and management of mineral resources were particularly contentious as the DRC was divided into military zones of control by the government, rebel groups, and their foreign backers. The Sun City Accords affirmed Congo’s unity within a provincial system to enable local autonomy within a unitary republic.

The Accords also sought to stabilize the mining sector through anti-corruption and accountability regulations, judicious implementation of labor laws, and equitable management of the country’s national wealth. These measures were codified into Congo’s legal framework.

Contested citizenship was another thorny issue. Successive Congolese governments have, at times, withheld recognition of the citizenship status of Congolese of Rwandan and Burundian descent, including the Banyamulenge and Banyamasisi. Playing on popular Congolese resentment toward Rwanda as a device to mobilize support, these tactics have rendered these communities stateless. This grievance, in turn, has been a tool for recruitment by all rebel movements emerging from the eastern DRC. They have been backed by Rwanda and Uganda, which sympathize with these groups based on their own historical experiences.

Article 32—The Need to Address Citizenship and Nationality Laws

Article 32 of the Sun City Accords acknowledged that Congo’s nationality laws were a source of uncertainty and tension as they were silent about the citizenship of certain minorities, particularly those of Rwandan and Burundian descent. This Article states that the politicization of the nationality of these segments of the population was “a major cause of Congo’s major crises, resulting in feelings of deprivation, hatred, and profound rifts in the population.” Furthermore, the Article warned that, “only real political will can guarantee the resolution of the crisis borne of the issue of nationality.”

The following six measures were adopted to address the matter:

- Recognition that all communities residing in areas that became the Democratic Republic of Congo at independence, enjoyed equal rights and protections as Congolese citizens.

- A provision for a population census for better planning, resource allocation, and identification of communities needing protection and enforcement of citizenship rights.

- Revision of citizenship laws to bring them in line with the Accords.

- A national program of awareness and reconciliation to counter negative sentiment and the targeting of minorities.

- A process by which dual citizenship could be explored.

- A pathway to an efficient judicial system to ensure that citizenship claims were handled professionally, speedily, and impartially.

Outcomes of the Inter Congolese Dialogue

The Sun City Accords gave Congo a new Constitution in 2005, an election in 2006 (the first since independence in 1960), a more democratic institutional architecture, and a strong culture of civic engagement and resistance to dictatorship that continues to date. The vigorous and active participation of civil society at Sun City is one of the hallmarks and defining features of the Inter Congolese Dialogue, which built on earlier traditions of civic engagement at the 1992 Sovereign National Conference, which was aborted in the period leading to the First Congo War. It should be recalled that about 40 percent of the signatories of the Sun City Accords were from civil society.

Notably, the negotiators at Sun City agreed that during the transitional period, the National Assembly should have strong civil society representation. Thanks to this, the period between 2006 and 2009 witnessed the emergence of a vibrant National Assembly and served as an effective check on executive authority. The lower chamber conducted 43 independent investigations leading to the sanctioning of ministers and reallocation of expenditures. The upper chamber oversaw 28 independent investigations that prescribed remedies for numerous cases of executive misconduct.

Persistent African diplomacy and international engagement and the strength of South Africa’s influence at the time was crucial to achieving the compromises that led to the Accords.

Lessons from Achievements and Shortcomings

The ICD shifted the momentum away from the military protagonists towards a strategic initiative involving Congolese civilian stakeholders. Mediators today will want to achieve a similar pivot.

A rigorous monitoring mechanism will be required to assess compliance with any agreement that emerges.

Drawing from the ICD, a multi-stakeholder meeting of Congolese actors should be assembled in a National Dialogue. This can set the agenda and identify issues that need to be resolved. Participants should include representatives from the unarmed opposition, civil society, faith-based organizations, and other notable civil society coalitions.

Diplomatic efforts to resolve tensions between the DRC, Rwanda, and Uganda must be strengthened to create an enabling environment for the National Dialogue. Previous experience has shown that if peace and stability are to come to the DRC, then regional and international pressure on the external parties needs to be sustained and the signatories held accountable.

A rigorous monitoring mechanism will be required to assess compliance with any agreement that emerges and take corrective measures when risks arise. A key lesson from the ICD is that this task cannot be left to politicians alone as they will find ways to walk back their commitments. Illustratively, while the post-ICD National Assembly initially included leading civil society components, the executive branch set its sights on abolishing this representation in the quest to reassert the centralization of authority. This occurred through electoral fraud to gain supermajorities in both chambers, partisan laws, bribery and corruption, and a lack of commitment to a cardinal principle from the Sun City Accords—that of co-equal branches of government. Since 2010, the National Assembly has been a shadow of its former self.

Similarly, the question of citizenship of Congolese of Rwandan descent continues to be weaponized by some political elites—and rebel groups.

If peace and stability are to come to the DRC, then regional and international pressure on the external parties needs to be sustained and the signatories held accountable.

Unscrupulous national elites also saw to it that key Sun City institutions like the Higher Council for Promoting Ethnical Conduct and Combating Corruption and a Special International Criminal Court to handle war crimes would not be set up. They similarly failed to hold a population census as required by the Accords. (The last census in the Congo was taken in 1964.) Part of the problem was that regional and international guarantors became less involved in monitoring compliance. That was left to the Congolese elites, who saw little incentive for doing so.

These lessons are relevant today. The ICD and Sun City Accords provided an effective roadmap for ending the last Congo War. However, they were not self-enforcing. Building on this roadmap to address the current crisis will require more attention on implementation and creating incentives to sustain adherence to agreed-to articles over time.

*Paul Nantulya was a participant-observer at the preparatory talks of the Inter Congolese Dialogue, the Dialogue at Sun City, and subsequent engagements.

Additional Resources

- Paul Nantulya, “Risk of Regional Conflict Following Fall of Goma and M23 Offensive in the DRC,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 29, 2025.

- International Crisis Group, “Fall of DRC’s Goma: Urgent Action Needed to Avert a Regional War,” Statement, January 28, 2025.

- Paul Nantulya, “Understanding the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Push for MONUSCO’s Departure,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 20, 2024.

- Peter Fabricius, “Once More into the Breach: SADC Troops in DRC,” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, February 9, 2024.

- Coralie Pierret, “The ‘Wazalendo’: Patriots at War in Eastern DRC,” Le Monde, December 19, 2023.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Rwanda and the DRC at Risk of War as New M23 Rebellion Emerges: An Explainer,” Spotlight, June 29, 2022.

- Kasaija Phillip Apuuli, “The Politics of Conflict Resolution in Congo: The Inter Congolese Dialogue,” Africa Journal for Conflict Resolution, Issue 1, 2004.

More on: Democratic Republic of the Congo