(Photo: AFP/Tony Karumba)

Kenyans will vote in August in their seventh presidential elections since the introduction of multiparty politics in 1991. The competitiveness of the elections, and uncertainty over the outcome, distinguishes Kenya from many of its neighbors. President Uhuru Kenyatta is stepping down, following the completion of his constitutionally limited two terms in office. This, too, makes the Kenyan elections noteworthy, given the recent trend of African leaders sidestepping term limits as a means of extending their time in power—to the detriment of stability. Rather, Kenya has a tradition of transfers of power even between candidates from opposing parties.

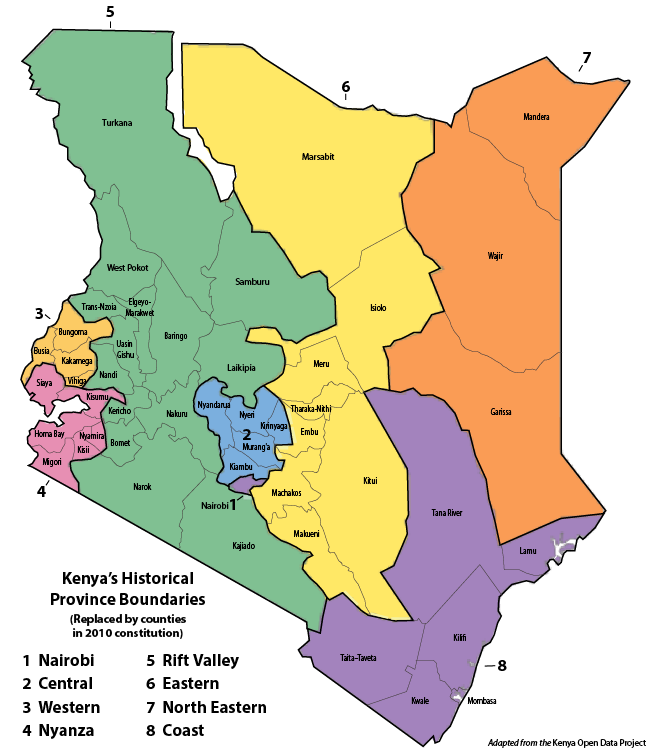

Still, elections in Kenya remain a period of high tension. Kenyans recall the large-scale violence that erupted after the 2007 elections when supporters of Raila Odinga, and his then running mate, William Ruto fought over what Odinga’s side saw as an effort by President Mwai Kibaki and his top lieutenants including (current President) Uhuru Kenyatta, to “steal” the election. The Rift Valley was engulfed in deadly violence pitting the Luo and Kalenjin communities—respectively loyal to Odinga and Ruto—against Kenya’s largest ethnic community, the Kikuyu, from which Kibaki and Kenyatta hail. Over 3,000 people were killed, and 600,000 uprooted. Many remain displaced today.

Kenya has a tradition of transfers of power between candidates from opposing parties.

The 2013 and 2017 polls, tightly contested between Odinga and Kenyatta (and his running mate, Ruto), were marred by electoral fraud. The Supreme Court required a rerunning of the 2017 contest due to the irregularities.

This recent history has raised questions about Kenya’s ability to hold free and fair elections—and the 2022 elections will provide a benchmark for how much progress has been made.

The potential for violence remains high according to a report by the independent National Cohesion and Integration Commission, due to pre-existing conflicts and weak institutions. Some young people have told the Commission that they are being paid by politicians to intimidate rivals and disrupt their campaigns. Kenyans’ trust in their institutions is low: only 26 percent trust the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), and just 23 percent trust the courts despite the courts’ taking high-profile stances of independence. A report by the Mozilla Foundation warns that hate speech, misinformation, and disinformation are widespread (though not by the candidates themselves), with some manipulated hashtags getting over 20 million views.

The Principals and Their Parties

A quintessential feature of Kenyan politics is that the same pool of politicians tends to dominate the political process, though they may be in different camps depending on the election— sometimes friends, sometimes bitter rivals. The whipping up of ethnic animosities, especially around land in the Rift Valley, is another feature of Kenyan politics. This is where some of Kenya’s most productive lands, previously reserved for European settlers, are located.

Raila Odinga. (Image: World Economic Forum/Matthew Jordaan)

The frontrunners of the upcoming polls embody many of these dynamics. Raila Odinga (77) and William Ruto (55) have worked together as senior government officers and, at times, as vigorous opponents in every election since the early 1990s. They were on opposite sides under President Daniel arap Moi, the same side against Mwai Kibaki in the infamous 2007 poll that ended in catastrophic violence in the Rift Valley, and are on opposite sides again this time around. The enmity between them has made this election more about personalities than policies.

Odinga is making his fifth and likely final run for office. He is currently viewed as a an “establishment candidate” since President Kenyatta is backing his candidacy following their famous “handshake” reconciliation in 2018.

Odinga’s Azimio La Umoja alliance (“Resolution in Unity” in Swahili) is a coalition of seven major political parties, three of which contested previous elections as bitter adversaries. This includes the Kenya African National Unity (KANU) that ruled Kenya as a one-party state until 2002 and once detained Odinga, the incumbent Jubilee/National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), and its rival from 2007 elections, the Orange Democratic Movement, then led by Odinga and Ruto.

The Azimio La Umoja alliance is organized around older-generation politicians dating back to the 1990s and a populist program, Inawezekana (“It Can Be Done”), that includes extensive social welfare initiatives: universal healthcare, Inua Jamii, Pesa Mfokoni (“uplifing the vulnerable together by putting money in their pockets”), which is a direct cash transfer of 6,000 shillings ($50) per month to needy families; and Azimio la Kina Mama (“the unity of our mothers and aunties”), which is universal financing for women-led small businesses.

William Ruto. (Image: World Trade Organization)

William Ruto had a falling out with Kenyatta in 2018, ending a two decades-old partnership dubbed “Uhuruto.” He presents himself as an “insurgent candidate,” deriding the Odinga ticket as a continuation of the dynastic politics of the Odinga and Kenyatta families that have loomed large over Kenya since independence.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga (Raila’s father) and Jomo Kenyatta (Uhuru’s father) were comrades who led Kenya to independence and were considered co-founding fathers until they fell out in the mid-70s over Jaramogi’s demand for multiparty politics. Ruto has framed his election around the slogan of Hustler Nation (aimed at those who are at the bottom of the social pyramid) and has depicted the elections as a struggle between “hustlers” and “dynasties.”

William Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza alliance (“Kenya First”) assembles nine parties that have also undergone multiple transformations since the Moi era. Some of them—like Ruto himself—were either on Odinga’s side or with Kenyatta in previous elections. It, too, promises an extensive and populist social welfare program targeted particularly at the youth. Key pledges include a so-called “hustler fund” for women’s cooperatives and Kenyan women abroad, workers compensation, universal healthcare, and Pesa Kwa Vijana (“putting money in the hands of the youth”), a program that targets “wealthy dynasties” for wealth and land redistribution. Ruto has also pledged to enact a policy requiring spousal consent in all land transactions to protect women and children from dispossession of family land.

It is notable that both tickets recycle elites who have dominated the Kenyan scene since the Daniel arap Moi era but under different banners. This serves to perpetuate the personalization of politics. Namely, parties have tended to be organized as vehicles for winning votes rather than offering alternative policies. Indeed, the two frontrunners—Odinga and Ruto—have traded accusations throughout the campaign, not on policy positions, but about their personal stories and having an unfair advantage due to their access to state machinery.

Kenyan political parties have tended to be organized as vehicles for winning votes rather than offering alternative policies.

These populist platforms are clearly targeting young people as a key constituency that is up for grabs. Kenya’s unemployment rate among the 18-to-34 age group is nearly 40 percent, and the economy cannot absorb the 800,000 youth joining the workforce annually. This is a restive cohort as can be seen in some of the placards at rallies that include slogans such as: “The youths are suffering,” “I lost my job,” “Vitu ni different kwa ground” (“things are different on the ground”), and “I need a job.” Such unmet expectations make this segment of society susceptible to being mobilized for violence.

Meanwhile, many other youth, typically the segment of the population that champions reforms, are apathetic—seeing little difference between the candidates and parties. The IEBC had set a goal of registering 6 million new voters given the growing youth cohort. Instead, it ended up only registering 2.5 million. Some of this lack of enthusiasm is a result of targeted disinformation, fostering confusion and disillusionment.

Some Lessons Learned

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution abolished what Kenyans have long described as an all-powerful “imperial presidency,” and redirected national politics down to the grassroots. A new government structure was adopted consisting of 47 counties, each with an executive authority and an independent legislative branch to debate and pass legislation. Mechanisms were put in place to facilitate public inputs in a bottom-up process. As a result, Kenyan politics have become more county-based, and politicians must create alliances at the municipal, village, and town levels.

Martha Karua. (Image: Tom Zed)

As one indication of this new mode of politics, Odinga and Ruto chose Kikuyu running mates, and have included Kikuyus up and down their tickets. Mount Kenya Province, where Kikuyus dominate, is the most populous constituency in Kenya, accounting for more than 17 percent of the vote.

In Odinga’s case, the choice of running mate is also a woman. Martha Karua, a High Court advocate and veteran of the struggle for multiparty democracy, is widely called “the iron lady.” She is the first woman to join a major party ticket in Kenya’s history. The Odinga camp is banking on her appeal with women, her anticorruption credentials, her endorsement from Mount Kenya Elders, and national recognition for her struggle against one-party rule.

Rigathi Gachagua. (Image: TheKenyanPen)

Ruto’s running mate, Rigathi Gachagua, is the first politician in Kenya’s electoral history to openly identify himself as a “child of Mau Mau”—the guerillas who fought the British colonialists, and whose struggle was centered in Mount Kenya region.

Gachagua’s parents serviced the guerillas’ weapons and provided them food and ammunition. By creating this aura around him, the Ruto side is trying to make a clever play on a highly emotive issue in Kenya’s political discourse. That is, despite the legendary status of the Mau Mau in Kenyan memories, there is a widespread perception that those who took over from the British distanced themselves from the Mau Mau and left them destitute.

Kenyan observers say that the selection of Kikuyu running mates sends a powerful message that Kikuyu, Luo, and Kalenjin elites can work together and presents an opportunity to move past ethnic-based politics

Both Odinga and Ruto have spent most of their campaigns outside their home turfs as they attempt to build on their strongholds. Odinga is dominant in 20 counties divided among his home Province of Nyanza, and the Provinces of Coast, Western, Northern, and Nairobi. Ruto is dominant in 15 counties located in South Rift—his home Province—and North Rift, Northern, and parts of Mount Kenya Provinces. This leaves Mount Kenya, Northern, Western, South Rift, and Coast as the key battleground provinces.

Some Kenyan observers say that the selection of Kikuyu running mates sends a powerful message that Kikuyu, Luo, and Kalenjin elites can work together and presents an opportunity to move past ethnic-based politics. This contrasts sharply with previous elections—especially 2007—when they were on opposite sides and old tensions between Kikuyu and Kalenjin peasants over land in the Rift Valley and between Kikuyu and Luo elites over Jomo Kenyatta’s perceived betrayal of Raila’s father were weaponized. The new alliances are seen by some as critical in healing these wounds. Others warn that such alliances do not necessarily guarantee peaceful outcomes but must be coupled with institutional mechanisms that constrain elites from resorting to violence.

The Institutional Guardrails

Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC)

Both Odinga and Ruto have complained that the IEBC is unprepared for the upcoming polls, raising alarm bells that the candidates might not accept the results. Notably, the IEBC Chairman, Wafula Chebukati, who was criticized by Kenya’s Supreme Court in 2018 for failing to respect constitutional rules, is still at the helm. At a meeting with European diplomats on June 2, 2022, Ruto complained that up to one million voters from his strongholds had disappeared from the voter rolls. Chairman Chebukati dismissed this as “rumors,” saying that the missing names are those of voters who applied to vote from different polling stations.

Adding to the confusion, the IEBC announced on June 9 that it would de-register 1.18 million voters following a preliminary audit by the international accounting firm KPMG, which found numerous discrepancies: dead voters, voters registered more than once, others with fake identification, and “ghost voters.” For his part, Odinga has made a list of 10 demands including making the audit public, ensuring the security of printing of ballot papers, testing the election technology, and amending laws granting power to presiding officers to open sealed ballot boxes to remove faulty materials at the tally center.

On June 27, the Elections Observation Group (ELOG), an independent forum of 15 local organizations, commended Chebukati for gazetting the voter rolls, but it is unclear if Odinga’s and Ruto’s concerns have been addressed. However, the ELOG—which monitors polls to ensure compliance with constitutional rules—warned that the IEBC’s decision to scrap the manual register in favor of a digital register on election day could be a recipe for chaos. Indeed, a serious crisis erupted in 2017 when 2.5 million manually registered voters were disenfranchised due to system failures. In June 2022, seven NGOs took the IEBC to court arguing that millions will again be disenfranchised if the system fails like it did in 2017.

In short, the IEBC’s apparent unpreparedness may heighten tensions and be grounds for subsequent court cases in the event of a contested outcome.

Judiciary

Kenya’s courts have delivered subsequent landmark rulings since the Supreme Court’s call for a rerun of the 2017 polls, demonstrating that this decision was not a one-off demonstration of independence. The blockage of the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) by both the High Court and Supreme Court was a shot across the bow that the judiciary is determined to remain more fearless than it was during the Moi and Kibaki administrations. If disputes erupt, complainants will undoubtedly cite the 2017 case, which set the precedent that solely requires them to show that constitutional requirements were violated as opposed to the past where they had to show irrefutable proof of undercounted votes—a much higher bar.

The 2022 electoral process has also been stoked by fears that if Raila Odinga were to win, he would bring back the BBI. The BBI was an outcome of the “handshake” between Odinga and President Uhuru Kenyatta in 2018. In 2020, it tabled sweeping constitutional amendments which among other things would have created the post of Prime Minister. Some have speculated that under an Odinga administration and a resurrected BBI the prime minister role would be given to Kenyatta, effectively extending his tenure and undermining the two-term rule.

Kenya High Court in Nairobi. (Source: Wing)

The BBI was thrown out as unconstitutional by the High Court in May 2021 in a unanimous decision by its seven members. In August 2021, the Supreme Court upheld the ruling and dismissed a government appeal. In a scathing decision, it warned that constitutional amendments cannot be forced through by executive whim. “The executive” it said, “cannot run with the hares and hunt with the hounds.”

The growing independence of Kenya’s courts may be a crucial factor in ensuring a credible electoral outcome and smooth transition.

Security Forces

Kenya’s military is traditionally apolitical and stays out of electoral contests. The police and paramilitary General Service Unit, however, are frequently accused of intimidating government opponents, employing violence, and disrupting opposition campaigns. This election poses a unique dynamic in this regard as the two front-runners enjoy incumbency status: Odinga as the “establishment candidate,” and Ruto as Deputy President. At face value, this makes it unlikely that their rallies will be disrupted, or their supporters intimidated and harassed. This cannot entirely be ruled out, however. The Independent Policing Oversight Authority and the National Police Service Commission were established in the past decade to strengthen oversight of the police and monitor compliance with human rights standards. Progress on this front has been slow, however.

Civil Society

Kenya’s civil society has persistently engaged in the democratic process. The ELOG is monitoring the entire process and has issued statements to the stakeholders at every stage, reminding them of their constitutional obligations and educating the public about the electoral process and their rights. Notably, they have deployed long-term observers at the county level and put in place an alternative voter tabulation system to independently verify the results.

The Ushahidi platform, an open-source tool created in the aftermath of the 2007 election violence will also be active. Voters can upload real-time data and send it to a central server for processing and forwarding to responders. Citizens can also collect real-time information on the polls, including around the voting centers. Thirteen partner organizations are part of this system, which will escalate the crowdsourced data for response and action. Kenya’s media agencies, which have provided extensive coverage and analysis since the campaigns started, will also participate in this project. This vigilance and engagement will create a valuable forensic record and remind political actors that they are being observed at each step.

Much Progress, More to Be Done

Continued citizen agency will be a vital check to remind political actors that they must operate within the boundaries of the law.

Kenya enters the homestretch of the 2022 electoral season building on the lessons of past fraught elections. Key among these are the 2010 Constitution, the growing independence of the judiciary, and an active civil society. Continued citizen agency will be a vital check to remind political actors that they must operate within the boundaries of the law.

These institutional guardrails will be especially important given the questions over the IEBC’s preparedness and ability to address the parties’ concerns. The depth of these institutions’ resiliency will be vital to ensuring the hotly contested election—and any subsequent challenges—generates an outcome that most Kenyans accept as valid. If Kenya’s electoral process navigates both the upholding of term limits and the peaceful transfer of power, it will be a major step forward for Kenyans’ long journey to a more robust democracy.

Additional Resources

- Charles A Ray, “Kenya’s Elections Will Come Down to the Wire,” Analysis, Foreign Policy Research Institute, June 28, 2022.

- International Crisis Group, “Kenya’s 2022 Election: High Stakes,” Briefing No 182, June 9, 2022.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Three Takeaways from the Kenya Supreme Court Ruling,” Spotlight, September 1, 2017.

- Godfrey Musila, “Legal Reforms Aim to Prevent Electoral Violence in Kenya,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 26, 2017.

More on: Democracy