A drug stash captured in the Indian Ocean.

Drug trafficking is a major transnational threat in Africa that converges with other illicit activities ranging from money laundering to human trafficking and terrorism. Drug trafficking often complicates and extends armed conflicts by providing revenue needed to purchase weapons, corrupting law enforcement and military officers, and diverting resources from efforts to defuse conflict. It also channels funding for terrorist groups, weakens the rule of law, perpetuates crime, and makes conflicts more lethal.

The Extent of the Problem

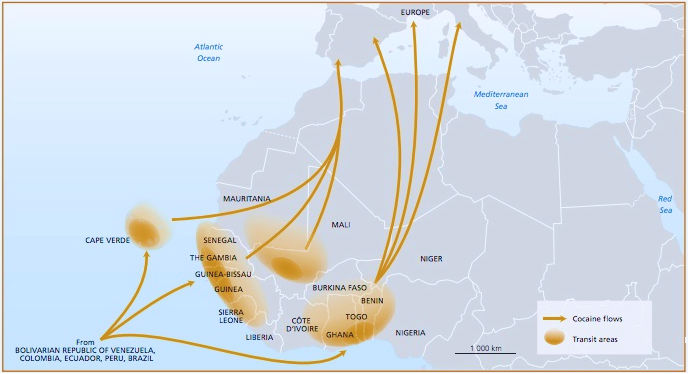

According to the 2017 UN World Drug Report, two-thirds of the cocaine smuggled between South America and Europe passes through West Africa, specifically Benin, Cape Verde, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Nigeria, and Togo. Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania are among the countries that have seen the highest traffic in opiates passing from Pakistan and Afghanistan to Western destinations.

UN map of cocaine flows through West Africa.

Terrorist organizations on the continent have taken advantage of the revenue opportunities created by controlling these trade routes for drugs. Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and its breakaway, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, are involved in cannabis and cocaine trafficking in the Sahel. Boko Haram has been implicated in cocaine and heroin smuggling across West Africa.Trafficking routes through West Africa vary. Some pass through Algeria, Mali, Mauritania, and Morocco and then on to southern Europe. Others cross the Atlantic bound for the United States. In many cases, Guinea-Bissau is a key trans-shipment point. Drawing on ties to senior political and security leaders, South American drug cartels have used Guinea-Bissau as a hub for many years to smuggle vast quantities of cocaine to Europe.

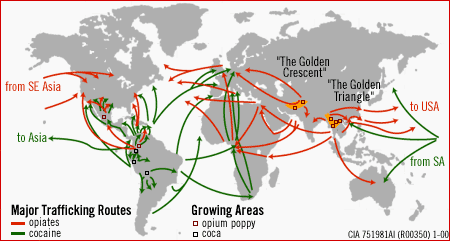

The so-called “southern route” stretches from Afghanistan and Pakistan through Iran, across the Indian Ocean to East Africa on its way to consumer markets in Europe and North America. Some shipments sail as far south as Mozambique and South Africa en route to transit hubs in East Africa. This circuitous route takes advantage of southern Africa’s good physical and communications infrastructure and enables drug trafficking networks to avoid detection. This gives them access to distribution systems through East Africa. In 2014, the multinational naval partnership that patrols the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean, seized a ton of heroin from a dhow in Kenyan waters. That single haul was roughly the same amount as all the heroin captured by 11 East African governments between 1990 and 2009.

Map of world drug trafficking routes. Image: CIA.

Cocaine coming from Latin America often stops in South Africa before being shipped to Europe and East Asia. In June 2017, South African police seized 500 million rand worth of cocaine (approximately $36 million) and 104 million rand worth of heroin ($7.7 million) in separate raids in Western Cape province. In 2016, several traffickers in this province were arrested in raids on shipments of heroin coming from Mozambique.

The Changing Nature of Criminal Syndicates and Regional Responses

The drug market has also become a ground for collaboration and competition between organized crime groups across national, linguistic, and ethnic divisions. In Africa, the involvement of organized crime groups is concentrated around the cocaine, heroin, and cannabis markets.

Reflecting the global nature of the trade, criminal groups involved in the drug trade are often made up of citizens from multiple countries. For instance, in 2010, police in Gambia seized more than two tons of cocaine worth $1 billion in the largest-ever drug bust in West Africa. In the raid, 12 foreign nationals from the Netherlands, Venezuela, Ghana, Mexico, and Nigeria were arrested. They were all employees of a Dutch-owned fishing company that served as a front for drug cartels using Gambia as a transshipment point.

As governments collaborate more in counter-narcotics, criminal groups are changing their structures and modifying their tactics.

With counter-narcotics collaboration among governments on the rise, criminal groups are changing their structures. Many have moved away from rigid hierarchical structures that are easily detected, to looser ones that are more nimble, enable members to communicate more rapidly, and deliver goods more effectively. Crime syndicates are also modifying their tactics, such as using low-level runners to collect cash before letting the customer know by text message where to collect their drugs. Such innovations, coupled with more horizontal organizational structures, have led to a proliferation of crime syndicates. In the European Union—an important hub in the African narcotics trade—5,000 organized crime groups were operational in 2017, more than in property crime, human trafficking, excise fraud, and other illicit activities.

One key instrument that governments are employing in dealing with these challenges is the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. It provides for extradition, confiscation of proceeds, mutual legal assistance, and anti-money laundering regulations, among other measures. The Gambian bust was aided by legal assistance provided to Gambia by British forensic experts under the terms of the convention. The British team worked with their Gambian counterparts to identify and trace the transactions, thereby learning more about the network as it evolved. Indictments generated from a subsequent sting operation in 2013 conducted in collaboration with U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency similarly generated valuable insights into the cooperation between Colombian drug cartels and senior officials in the Guinea-Bissau navy, most notably its former chief, Rear Admiral José Américo Bubo Na Tchuto.

Corruption and Poor Governance

The multinational nature of criminal networks makes it very difficult for any individual country to have visibility on an entire narcotics network.

An incident on March 25, 2011, involving one of the largest drug interceptions in Kenya’s history further underscores this danger. The authorities reported that a ship en route from Pakistan loaded with more than three tons of heroin had anchored in Mombasa for more than 10 days, during which local and international drug traffickers used speedboats to purchase drugs from the ship before finally being apprehended. According to police, a suspected Nigerian drug baron, Somalis linked to piracy, and a Mombasa businessman were among the purchasers. Three days after announcing that 196 kilograms of heroin had been intercepted, the police revised the figures to 102 kilograms of heroin. Speculation was rife that the 94 kilogram discrepancy was due to fraud and corruption, though some police blamed it on the wrapping materials used to carry the drugs.

According to one press report, a politician with powerful connections was behind the entire shipment and that almost a week after the seizure, he had not yet been questioned. For its part, the police complained that this individual enjoyed the protection of an unnamed official in the internal security ministry and that the beneficiaries of the haul were attempting to frustrate their investigations.

“Some of them are boasting in public places, saying that police are useless and have tried to compromise, demoralize, and intimidate officers pursuing the case. Let the beneficiaries know that the war is still on,” warned then–police spokesperson Eric Kiraithe in a stern statement.

Networks’ ability to penetrate political systems and the enabling environment created by corruption often generates “inside help” in avoiding detection.

This case highlights several aspects of the counter-narcotics challenge. The multinational nature of criminal networks makes it very difficult for any individual country to have visibility on an entire narcotics network. Moreover, these networks’ ability to penetrate political systems and the enabling environment created by corruption often generates “inside help” in avoiding detection. Such security gaps explain why West African smugglers are attracted to East Africa as a transshipment point into Europe.

Recognizing the challenge, West African leaders established the West African Coast Initiative (WACI) in 2009. This multinational partnership comprises the four most vulnerable countries in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)—Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—as well as the UN Office for West Africa, the UN departments of Political Affairs and Peacekeeping Operations, and Interpol. WACI employs a multisector approach to strengthen law enforcement and justice institutions and manage transnational crime units in each of the four countries for interagency coordination, cross-border collaboration, and joint action. Thanks in part to these efforts, large seizures of cocaine in the region began to drop (an estimated 18 tons of cocaine moved through the region in 2010, compared to 47 tons in 2007, according to UNDOC). In 2013, the UNDOC reported a continued decline in the influence of South American criminal groups in the West African narcotics market.

Recognizing the challenge, West African leaders established the West African Coast Initiative (WACI) in 2009. This multinational partnership comprises the four most vulnerable countries in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)—Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—as well as the UN Office for West Africa, the UN departments of Political Affairs and Peacekeeping Operations, and Interpol. WACI employs a multisector approach to strengthen law enforcement and justice institutions and manage transnational crime units in each of the four countries for interagency coordination, cross-border collaboration, and joint action. Thanks in part to these efforts, large seizures of cocaine in the region began to drop (an estimated 18 tons of cocaine moved through the region in 2010, compared to 47 tons in 2007, according to UNDOC). In 2013, the UNDOC reported a continued decline in the influence of South American criminal groups in the West African narcotics market.

The disruptions to the networks’ operations have forced traffickers to develop new routes and tactics, with local syndicates taking over many aspects of the illicit trade. Nonetheless, with WACI in place, stakeholders now have a mechanism to study and adapt to new trends. Replication of the WACI model is now taking place in southern and eastern Africa.

“It takes a network to defeat a network.”

Africa Center Expert

Benjamin Nickels, Associate Professor of Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency

Additional Resources

- André Standing, “Criminality in Africa’s Fishing Industry: A Threat to Human Security,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 33, June 6, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Illicit Financial Flows to and from Africa: A Conversation with Raymond Baker,” interview, July 28, 2015.

- R. Mailey, “The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’s Extractive Industries,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Special Report No. 3, May 31, 2015.

- Mark Shaw, Tuesday Reitano, and Marcena Hunter, “Comprehensive Assessment of Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime in West and Central Africa,”African Union, January 2014.

- Davin O’Regan and Peter Thompson, “Advancing Stability and Reconciliation in Guinea-Bissau: Lessons from Africa’s First Narco-State,”Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Special Report No. 2, June 30, 2013.

- Peter Gastrow, “Termites at Work: A Report on Transnational Organized Crime and State Erosion in Kenya,” International Peace Institute, 2011.

More on: Counter Narcotics Countering Violent Extremism Corruption Governance