A China Mobile display at the 2023 Africa Tech Summit in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo: AFP/Xinhua/Han Xu)

Africa’s reliance on foreign suppliers for the continent’s technology infrastructure is widely seen as a major cybersecurity vulnerability. The most prominent example of this was when network engineers at the African Union (AU) headquarters in Addis Ababa uncovered a massive ongoing cyber espionage campaign at the Chinese-built facility. Dating back to 2012, troves of sensitive data from AU systems were being transmitted to Shanghai each night between 12 and 2 a.m. Other cases of Chinese cyber espionage include the infiltration of key government ministries in Kenya as the two countries wrangled over debt and continued surveillance of the AU via Chinese-supplied closed-circuit television cameras.

The challenge for African countries is how best to reap the benefits from externally supplied technology while safeguarding Africa’s critical infrastructure.

These high-profile incidents are part of a pattern of external actors in Africa and across the world leveraging their influence over technology infrastructure, supply chains, and government buildings to engage in cyberattacks. Underscoring this vulnerability, Chinese companies have built nearly 200 government buildings in Africa and at least 14 sensitive intragovernmental telecommunications networks. Beijing has also donated computers to at least 35 African governments.

Because information and communications-based infrastructure increasingly underpins everyday life, opportunities for exploitation are likely to increase. In the first quarter of 2023 alone, attacks were detected against one-third of the continent’s computers that operate sensitive industrial control systems. Cyberattacks, linked either directly or indirectly to external state actors, have had major impacts on the finance, public services, and port infrastructure sectors of various African countries in recent years.

At the same time, externally supplied information and communications technologies make indispensable contributions to Africa’s technological development and the well-being of millions of Africans. Foreign suppliers will remain influential actors in tech spaces for the foreseeable future. The challenge for African countries, then, is how best to reap the benefits from externally supplied technology while safeguarding Africa’s critical infrastructure.

Unpacking the Tech Stack

The technology sector is vast, incorporating everything from programming languages that create software, to routers that provide wireless connectivity, to satellites that power GPS systems. Analyses of external actor influence in African technology spaces rarely examine the technology sector holistically. Most focus only on the influence of one external actor, such as China or the United States, or one aspect of the tech sector, such as hardware.

The concept of a technology stack, or tech stack, provides a useful framework for thinking more comprehensively about the key actors and activities in the technology sector. It consists of at least five layers, beginning with those that interact most with the user and ending with technology service providers. These include:

Mapping External Actor Influence in the African Tech Stack

Africa’s tech stack has numerous vulnerabilities to external influence across and within each layer. A smartphone manufacturer can influence the user through the security of the hardware it uses and the ecosystem of pre-loaded applications it chooses. The maker of an application can either knowingly or unknowingly introduce vulnerabilities via the update process. Through their control over physical networks, service and infrastructure providers have significant latitude to monitor, mediate, and even shut down the access of users to telecommunications resources. Both private enterprises, through incentives to make profits, and state actors, who have significant interests in the information and cyber domain, have means of influencing each layer.

While external actors have substantial influence across most layers of Africa’s tech stack, there is wide variation between and within each layer.

Application Layer

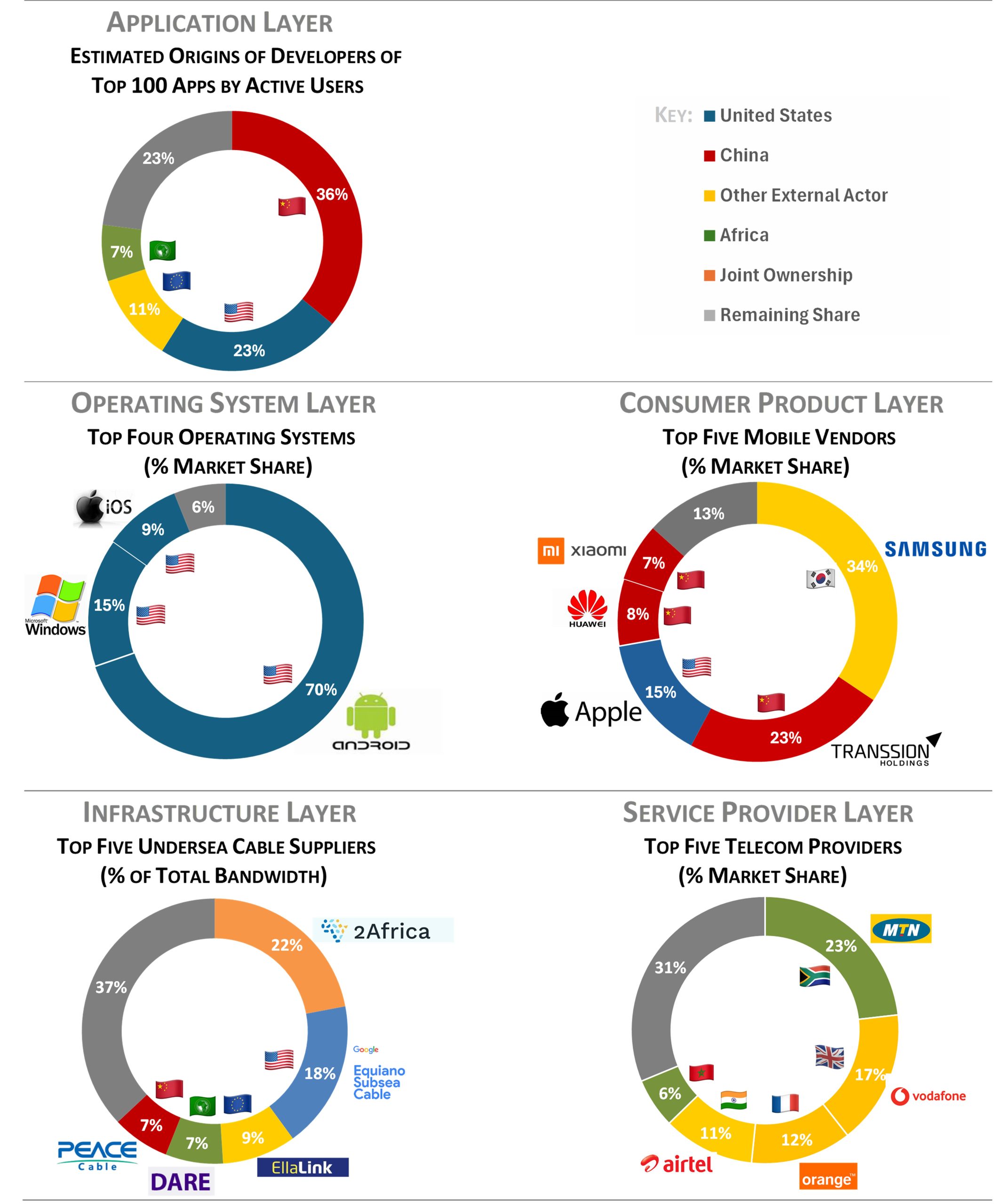

- China and the United States are the two most significant players in Africa’s application market. Chinese developers produced 36 of the top 100 apps employed by active users, followed by 23 from the United States, 11 from Europe, and 7 from Africa.

- When it comes to Africa’s top five mobile apps by the number of active users, Google (Chrome, YouTube, and Calendar) and Meta (WhatsApp), hold the top four spots, with China-based CloudView’s Phoenix Browser is fifth.

- U.S. companies such as Meta, Google, and LinkedIn operate the most used social and communications apps, where African users spend most of their time. Meta’s WhatsApp is far and away the continent’s most used messaging app, with over 90-percent usage in tech-driven African economies such as Kenya and South Africa. TikTok, owned by the China-based ByteDance, is quickly gaining market share.

Operating System Layer

- The United States is by far the dominant player in the operating system layer. U.S. companies such as Google (Android), Microsoft (Windows), and Apple (iOS), possess over a 90-percent market share of Africa’s operating systems.

- The United States’ dominance in this sector is not exclusive to Africa. Worldwide, these same companies and systems possess 97 percent of the market.

- HarmonyOS, China-based Huawei’s operating system, is the nearest competitor. It has already become the second-best selling mobile operating system in China, and could challenge the dominance of U.S.-made operating systems as its availability becomes more widespread. Given the fact that many cyberattacks exploit vulnerabilities in operating systems, as well as the role that operating systems play in shaping the entire ecosystem of applications available to users, the implications could be significant.

Consumer Products Layer

- In Africa’s consumer products layer, Asian countries such as China and South Korea are among the continent’s principal suppliers. Samsung, the Korean telecommunications giant, is the largest vendor of mobile devices in Africa, with 31 percent of the market.

- The Chinese conglomerate, Transsion, which includes the vendors Techno and Infinix, is second, with a 21-percent market share. The Chinese companies Huawei and Xiaomi each possess about 7 percent of the market. This gives China-based enterprises 36 percent of the market share, the largest of any single country.

- China is also becoming increasingly dominant in the provision of smartphones, now the most common device Africans use to access the internet. Two Chinese companies, Transsion and Xiaomi, supply over 60 percent of Africa’s smartphones. They have taken market share from Samsung, which now controls only 22 percent of the market. Apple (and its popular iPhone) is the third largest supplier with 13 percent of the market.

External Actor Involvement in Africa’s Technology Stack: Select Layers and Markets

Sources: Datasparkle 2023 and 2024 (Application layer); StatsCounter (Operating systems); StatsCounter, Many Possibilities (Consumer products); GSMA, Morocco World News, Orange, Airtel, Vodacom, MTN (Service Providers).

Infrastructure Layer

- By many accounts, China dominates the provision of Africa’s telecommunications infrastructure. Chinese companies such as ZTE and Huawei have reportedly built as much as three-quarters of Africa’s existing 3G, 4G, and emergent 5G network infrastructure.

- China is also a major player in supplying other aspects of telecommunications infrastructure such as land-based fiber optic cables, routers, data centers, satellites, base stations and undersea cables.

- The markets for some types of infrastructure, such as satellites, data centers, and undersea cables, are quite competitive. In looking at Africa’s top five suppliers of undersea cable by total overall bandwidth, China’s PEACE Cable barely cracks the top five. African (the DARE), European (EllaLink), and U.S. suppliers (Equiano) all run larger cables. Collectively, these five cables are responsible for two-thirds of all the undersea cable bandwidth serving Africa.

- The largest undersea cable serving Africa, 2Africa, is managed by a consortium of companies that include China Telecom, Meta, MTN, Orange, Vodafone, Egypt Telecom, and WIOCC. The cable itself is built by Alcatel Submarine Networks, a subsidiary of the Finnish Company, Nokia.

Service Providers

- There is similar diversity among Africa’s top five major telecommunications providers, some of the largest and most influential entities in Africa’s tech sector. In contrast to other layers, neither the United States nor China is a major player.

- The South Africa-based MTN, with close to 300 million subscribers, is Africa’s largest telecom, with 23 percent of the market.

- Next is the UK-based Vodacom (200 million, 16 percent) and France-based Orange (150 million, 12 percent). The Indian firm, Airtel, is Africa’s fourth largest telecommunications provider, with about 11 percent of market share (150 million subscribers), followed by Maroc Telecom, with about 6 percent (80 million).

- Collectively, these five companies account for about two-thirds of all telecommunications subscribers in Africa.

Across Africa’s tech stack, U.S.-based enterprises account for 9 and China-based enterprises account for 6 of the largest providers. However, external firms are neither limited to the United States or China nor are most layers without diversity and competition. Outside of the operating systems layer, at least one non-U.S. or Chinese actor possesses significant market share, be it Europe in the application, infrastructure, and service provider layers, South Korea in the consumer product layer, or India in the service provider layer.

Origin of Top Five Providers in Africa’s Tech Stack

Country | Applications (Active Users) | Operating Systems | Tech Stack Layer Consumer Products (Mobile Vendors) | Infrastructure (Cables) | Service Providers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Chrome YouTube Calendar | Android Windows iOS | Apple | Equiano | 9 | |

| China | Phoenix Browser | HarmonyOS | Transsion Huawei Xiaomi | PEACE | 6 | |

| Europe | EllaLink | Vodacom Orange | 3 | |||

| Africa | DARE | MTN Maroc Telecom | 3 | |||

| Other | Linux | Samsung | 2Africa | Airtel | 4 | |

| Total | 25 |

Sources: Datasparkle 2023 and 2024 (Application layer); StatsCounter (Operating systems); StatsCounter, Many Possibilities (Consumer products); GSMA, Morocco World News, Orange, Airtel, Vodacom, MTN (Service Providers)

Grounded in African Agency

Despite the importance of external actors, African enterprises, regulators, consumers, and tech workers are the single most important players in Africa’s tech sector. Their decisions determine how technology is deployed, mediated, and used.

What determines success is not the origin of the supplier but the suitability of a technology product to the African market.

While external actors supply much of Africa’s technology, African enterprises play a critical role in the African tech stack’s application, infrastructure, and service provider layers. The single largest telecommunications provider in Africa, MTN, is a multinational firm based in South Africa. Other large state-owned enterprises, such as Maroc Telecom and Ethio Telecom, are major players as well. Africa’s fourth largest undersea cable by bandwidth, the Djibouti Africa Regional Express (DARE) cable is owned and operated by a consortium of Africa-based telecommunications firms. African developers are major players in application markets such as e-commerce, where the Nigeria-based Jumia is the second-most used app. In finance, Africa-based enterprises such as OPay, PalmPay, and M-Pesa all rank in the top 10 most used apps.

Moreover, foreign companies that own parts of Africa’s tech stack depend heavily on Africa-based franchises and workforces. In most cases, the relationship between the external actors supplying hardware, software, or management expertise, and African governments, consumers, and enterprises is symbiotic and mutually beneficial.

For example, the UK-based Vodafone possesses a 40-percent management stake in Safaricom, Kenya’s largest telecommunications company, which operates as a semi-independent subsidiary. The government of Kenya retains a 35-percent stake, generating revenue on licensing fees and taxes. Safaricom employs over 6,000 people, has around 45 million subscribers, and, according to company figures, sustains 1.2 million jobs, or around five percent of the Kenyan workforce.

A girl browses products in a mobile shop in Ethiopia. (Photo: AFP)

African governments play a crucial role in driving investment and enforcing regulations that set guardrails around how technology is deployed. Collectively, African governments spend more on financing ICT infrastructure than external state actors. Moreover, private investment in Africa’s digitization outnumbers government-driven investment by a factor of four to one. African governments possess a diverse array of legal, regulatory, and legislative frameworks. For example, five African countries rank in the top tier of the International Telecommunication Union’s Global Cybersecurity Index, while four rank among the bottom. Some, such as Ghana, possess cybersecurity legal and regulatory frameworks that are a potential model for other countries across the world.

Most importantly, it is citizens as the end users of technology that drive demand. What determines success is not the origin of the supplier but the suitability of a technology product to the African market. George Zhu, the founder of Transsion, spent a decade in Africa before founding the company. Transsion’s flagship Tecno-branded phones are highly adapted to the African consumer and, in addition to low costs, include features such as long battery life, space for multiple SIM cards, keyboards in local languages, and the ability to recognize dark-skinned faces in low contrast. This attention to detail is what has enabled the company to stand out in comparison to its competitors.

Mitigating External Sources of Cyber Risk

Africa is far from unique in its dependency on external actors to supply critical technologies. Due to the globalized nature of technology supply chains, networks effects, and the highly specialized production of technologies such as semiconductors and leading generative Artificial Intelligence models, all countries possess technological dependencies.

Diversity and competition within the tech sector … can help mitigate vulnerabilities.

Yet, a detailed view of Africa’s technology sector reveals that it is not under the control of any one actor, and there are plenty of opportunities for Africans to assert agency. By further fostering diversity and competition within the tech sector, African governments can help mitigate the vulnerabilities that come from external actor influence.

As Africa’s own technology industry continues its rapid growth, undertaking additional cybersecurity priorities will help African governments ensure the safety of their countries and citizens from cyber threats.

First, security-minded customers and strategically sensitive industries should select products and work with firms that prioritize cybersecurity. Across Africa, for example, Meta’s WhatsApp is the most popular messaging app, and is commonly used by security and government officials to communicate. By contrast, the messaging app Signal offers stronger encryption, collects less data on its users, and does not share this data with advertisers or government. Like WhatsApp, it is easy to download and free to use. For government, security sector officials, and citizens with espionage concerns, Signal may be a superior choice.

Second, for strategic technologies that cannot be produced or adequately safeguarded within a country, African states should seek to foster diversity and competition. For example, cuts to undersea cables serving Africa have historically caused major problems, leading to disruptions or internet service outages that last months. The greater the diversity and bandwidth of undersea cables serving Africa, the more resilient internet service will be—and the more options that become available for routing potentially sensitive traffic.

Third, African governments have a critical role to play in strengthening cyber capabilities by establishing legal, legislative, and institutional frameworks to mitigate cyber risk, particularly in critical sectors such as energy, finance, telecommunications, and government. Nevertheless, many countries lack comprehensive policies to protect critical information infrastructure. Even those countries with policies often lack specificity about the assets that need protecting, such as industrial control systems in power plants or automated systems that unload assets in ports.

Finally, African governments should engage in regional and international efforts to protect critical information infrastructure from cyberattacks, a critical component of the universally agreed-upon norms of state behavior in cyberspace. African governments have much to gain from increased diplomatic and defense sector engagement on implementing these norms, which include global cyber capacity building initiatives building to enable African governments to better identify, detect, and respond to attacks themselves. African countries should also deepen their engagement in efforts led by the AU, regional economic communities, and national computer emergency response bodies to protect shared critical infrastructure in the public, energy, maritime, financial, and telecommunications sectors.

Additional Resources

- Nate Allen, “Critical Information Infrastructure Protection in Africa,” Stellenbosch University Security Institute for Governance and Leadership in Africa (SIGLA) Research Brief, June 24, 2024.

- Ayantola Alayande, “Africa and the U.S.-China Tech Competition,” Dataphyte, April 17, 2024.

- Kenneth Adu-Amanfoh and Nate D.F. Allen, “Learning from Ghana’s Multistakeholder Approach to Cyber Security,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 3, 2023.

- Tom Hegel, “China’s Continental Takeover,” Sentinel Labs, September 2023.

- Bulelani Jili, “Chinese ICT and Smart City Initiatives in Kenya,” The National Bureau of Asian Research, 2022.

- Motolani Agbebi, “China’s Silk Road and Africa’s Technological Future,” Council on Foreign Relations, February 1, 2022.

- Emily de La Bruyère, Doug Strub, and Jonathon Marek, eds., China’s Digital Ambitions: A Global Strategy to Supplant the Liberal Order, National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR), NBR Special Report No. 97, National Bureau of Asian Research, 2022.

- Aleksandra Gadzala Tirziu, “Partnering for Africa’s Digital Future: Opportunities for the United States, South Korea, and India,” Issue Brief, Atlantic Council, April 18, 2021.

- Nate Allen and Noëlle van der Waag-Cowling, “How African States Can Tackle State-Backed Cyber Threats,” Brookings Institution, July 15, 2021.

- Henry Tughendat, “The Evolving U.S.-China Tech Rivalry In Africa,” U.S. Institute of Peace, May 5, 2021.

- Joshua Meservey, “Government Buildings in Africa are a Likely Vector for Chinese Spying,” The Heritage Foundation, May 20, 2020.

More On: Africa’s Emerging Cyber Threats