The inauguration of Ghana’s Joint Cybersecurity Committee. (Photo: Cyber Security Authority)

The inauguration of Ghana’s Joint Cybersecurity Committee. As internet penetration has exponentially grown, African countries have become more exposed to cyber-related threats. Increasingly organized malicious actors deploy increasingly sophisticated forms of malware that threaten critical maritime and energy infrastructure, cause billions of dollars in annual losses, disrupt internet access, and steal sensitive information from governments, politicians, businesspeople, citizens, and activists across the continent. Most African countries have experienced at least one publicly documented disinformation campaign, a majority of which are sponsored by external actors.

Unfortunately, most African countries have yet to establish foundational cybersecurity policies to confront these threats. A majority have yet to author a national cybersecurity strategy, to set up institutions capable of responding to major cybersecurity incidents, or to define an approach to international cooperation in cyberspace.

“Ghana has placed a citizen-centric, multistakeholder approach at the core of its efforts to address the country’s cybersecurity challenges.”

Ghana is not most African countries. It is 1 of only 12 nations in Africa to possess both a national cybersecurity strategy and national incident response capabilities. It is also one of only four to have ratified both the Budapest and Malabo Conventions, two major treaties aimed at addressing the international dimensions of cyber-related threats.

Just as impressively, Ghana has placed a citizen-centric, multistakeholder approach at the core of its efforts to address the country’s cybersecurity challenges. Civilians are in leadership roles in shaping most aspects of cybersecurity policy and strategy, from defining interagency responsibilities to developing incident response capabilities. Other countries across the continent have much to learn from Ghana’s approach, which has brought tremendous growth in cyber capabilities, enabled Ghana to take action to address rising threats, and reinforced trust between the government and citizens.

A Civilian-Led Approach to Cyber Strategy

In many countries across the world, a national security agency serves as a country’s lead authority in charge of cybersecurity. While security sector involvement in cybersecurity is essential, security actors may not be sufficiently versatile to effectively steward a country’s information ecosystem. Furthermore, it can be costly, ineffective, and undermine trust between public, private, and civilian stakeholders.

The experience of Ghana illustrates the merits of a civilian-led approach to cybersecurity strategy and policy. When he took office in 2017, President Nana Addo Dankwah Akufo-Addo inherited implementation of the 2015 National Cybersecurity Policy and Strategy (NCPS). Though Ghana’s National Security and Foreign Affairs Ministries sought responsibility of the implementation of the NCPS, President Akufo-Addo selected Ghana’s Ministry of Communication and appointed a National Cybersecurity Advisor within the ministry to serve as the country’s top cybersecurity official. The decision was taken for a number of reasons:

- Cybersecurity threats were pervasive and involved nearly all citizens in the country

- Perceived benefits to the country’s Information, Communications, and Technology sector from an improved cybersecurity posture

- Drafting of the strategy and policy were done at the Ministry of Communications, placing it in the best position to lead implementation

- Concerns that a cybersecurity infrastructure dominated by national security officials would reduce public trust and make interagency cooperation more difficult

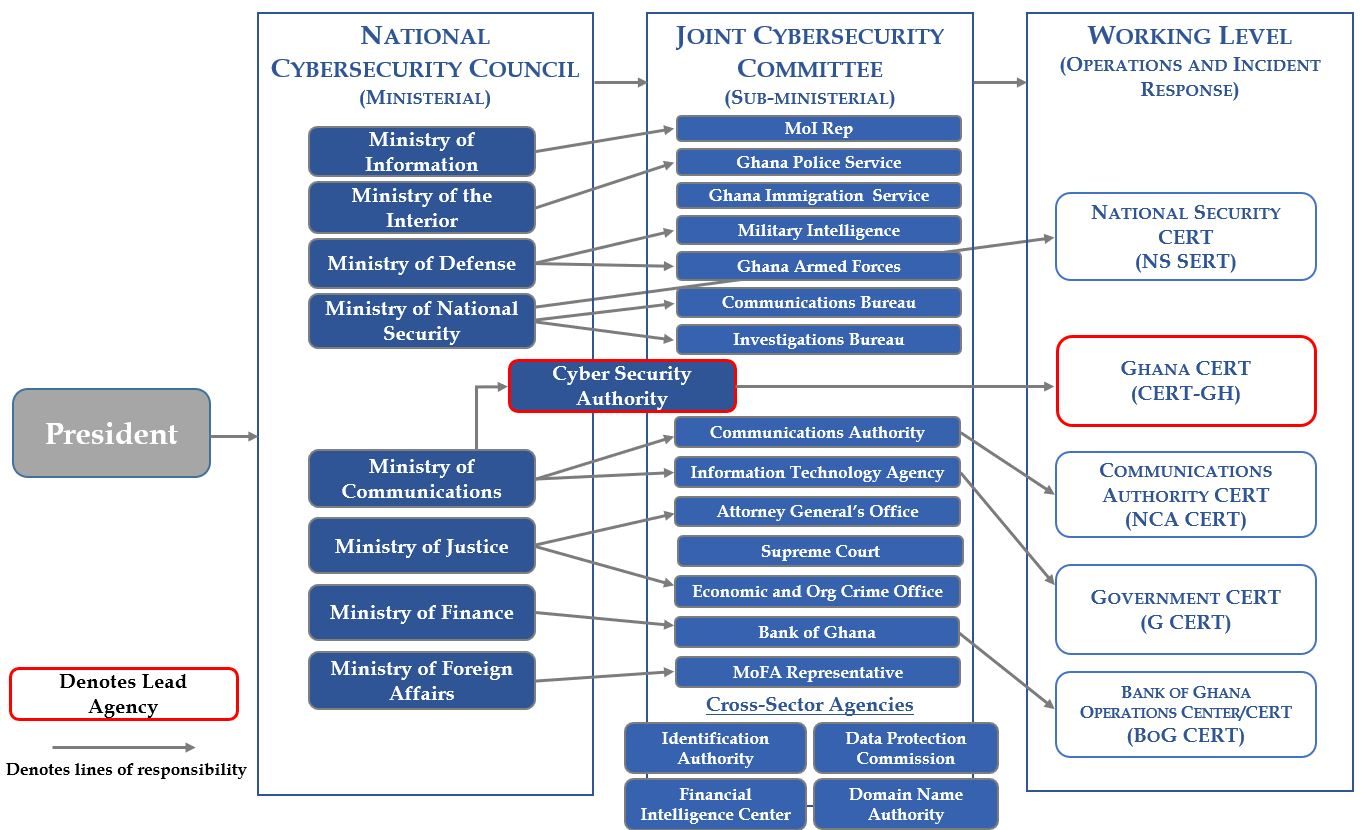

Under the leadership of the National Cybersecurity Advisor, Ghana established a three-tiered governance structure with key civilian, security sector, and nongovernmental stakeholders. First, a ministerial-level National Cybersecurity Council chaired by the Minister of Communications was established to take high-level cybersecurity decisions.

The National Cybersecurity Council was supported by a Joint Cybersecurity Committee (JCC) that oversees the day-to-day implementation of Ghana’s national cybersecurity strategy. The JCC is composed of both sub-ministerial-level government departments and agencies, and advised by nongovernmental actors, each with the authority to enforce the implementation of the NCPS in their respective agencies.

Finally, a National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) was established to oversee and coordinate all day-to-day national cybersecurity activities. Renamed the Cyber Security Authority (CSA) in 2021, it houses Ghana’s National Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-GH), serves as the government’s cyber threat intelligence nerve center and helps coordinate the response to major cybersecurity incidents.

Ghana’s Three-Tiered Cyber Security Governance Architecture

These efforts have rapidly built Ghana’s cybersecurity institutions by defining clear interagency roles and responsibilities. Both horizontal and vertical lines of communication and accountability enable decisions to be rapidly taken at an appropriate level and by the appropriate agency.

As a result, Ghana has emerged as a regional leader in cybersecurity. In just 3 years, it moved up over 40 places in the International Telecommunications Union’s Global Cybersecurity Index, from 89th to 43rd, making it 1 of only 7 African countries in the top 50 places (including Mauritius, Egypt, Tanzania, Tunisia, Nigeria, and Morocco). It has also become actively involved in strengthening cyber capacity in neighboring countries, including Sierra Leone and The Gambia.

Developing Leading Incident Response Capabilities

Ghana’s civilian-led, inclusive approach to cybersecurity has allowed the country to rapidly develop incident response capabilities. These capabilities are crucial in helping government, private sector, or civilian institutions identify malicious cyber threats and prepare and recover from attacks.

Ghana’s incident response architecture dates to 2014, with the establishment of Ghana’s National Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-GH) under the authority of the Ministry of Communications (now Ministry of Communications and Digitalisation). CERT-GH serves as the country’s focal point for computer security incident response. It possesses the capability to visualize Ghana’s cybersecurity threat landscape in real-time. It also operates an information sharing platform to share threat intelligence and response to security incidents in coordination with international, local, and private sector stakeholders.

Ghana’s Cyber Security Authority won the 2022 Cybersecurity Regulator of the year award at the Ghana Information Technology and Telecom Awards.

Ghana has also stood up a robust network of CERTs at the sectoral level. The sectoral level CERTs draw on technical expertise, domain specific authorities, and close relationships with the private sector to help secure critical infrastructure within their sectors from cyberattacks. To date, Ghana has established effective sectoral level CERTs in the banking, government, telecommunications, and national security sectors. These capabilities put Ghana far ahead of most African countries. Only 21 of Africa’s 54 countries have established the equivalent of a national CERT and 9 have sectoral level CERTs.

This robust incident response architecture has helped improve Ghana’s resilience to cyberattacks, particularly in vulnerable sectors such as banking. Amid rising cyberattacks in Ghana’s financial sector, the Bank of Ghana’s CERT set up a security operations center that enabled it to monitor cybersecurity incidents in real time and facilitate the sharing of threat information. In 2018, the Bank issued a Cyber and Information Security Directive that encouraged commercial banks to establish incident reporting mechanisms and dedicate human and physical resources to improve their cybersecurity posture. The Bank of Ghana and industry representatives have attributed significant declines in cyber fraud, from 174 cases in 2018 to 28 in 2020, to the passage of the Directive.

Leveraging External Partnerships

Ghana has managed to build its cybersecurity infrastructure relatively quickly in part because of the external partnerships it has forged. These partnerships have been leveraged by the country’s leaders to build cyber capacity in alignment with Ghana’s objectives and interests.

Leading nonprofit incident management organizations, including the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST) and AfricaCERT, helped establish Ghana’s first CERT (CERT-GH) and enabled CERT members to receive training and access to global cyber threat monitoring networks. The intelligence received through participation in these networks enabled CERT-GH to identify and help network operators recover from several significant cybersecurity incidents. Assistance Ghana received through the U.S. Security Governance Initiative supported the drafting of Ghana’s national cybersecurity strategy and informed the development of Ghana’s sectoral CERTs. The World Bank helped provide Ghana’s incident responders with state-of-the-art equipment.

“Ghana’s experience illustrates the degree to which the development of national cyber capacity can be nurtured through savvy external partnerships.”

The Ministry of Communications requested that Oxford University perform a cybersecurity capacity maturity model assessment for Ghana in 2018. Following this assessment, Ghana took steps to improve informal and formal cooperation mechanisms to respond to cybercrime and to train judges and prosecutors on how to handle digital forensic evidence. These improvements allowed Ghana to accede to the European Union-sponsored Budapest Convention on Cybercrime in 2018 and to ratify the African Union-sponsored Malabo Convention in 2021. Ghana is only one of four African countries to have ratified both conventions, and its accession to these important treaties has helped solidify Ghana’s reputation as one of the continent’s cybersecurity leaders.

But Ghana’s accession to these treaties has done much more than that. Both the Budapest and Malabo Conventions provide ratifying states with a common series of protocols, standards, and procedures for providing legal assistance, collecting and exchanging evidence, and holding cybercriminals to account. In a world where malicious actors based in Lagos, Prague, or Moscow routinely attack networks in Accra, the accession of more African countries to these important treaties will be essential to coordinate a response to globalized threats.

Ghana’s experience illustrates the degree to which the development of national cyber capacity can be nurtured through savvy external partnerships, and how the development of national cyber capacity can, in turn, improve global cyber resilience.

A Multistakeholder, Rights-Oriented Approach to Cybersecurity

A final benefit of civilian leadership is that Ghana has resisted the rising winds of digital authoritarianism. It ranks third among African countries in terms of overall internet freedom. Moreover, unlike many countries across the continent, the government is constrained from censoring internet content, political organization, or freedom of expression. This has enabled Ghana to build cyber capacity in a transparent manner that has helped reinforce trust between government and citizens.

Civil society in Ghana has taken on a higher profile role in recent years in ensuring government accountability and elevating attention on cybersecurity. Nongovernmental organizations such as the Africa Cybersecurity and Digital Rights Organisation, the Media Foundation for West Africa, and Child Online Africa have organized events, raised awareness, and directly informed the development and implementation of Ghana’s national cybersecurity strategy and policy. Ghana’s Cyber Security Authority works closely with civil society and private sector institutions on campaigns during Ghana’s annual National Cyber Awareness Month each October.

Formal opening of the Climax Week of Ghana’s National Cyber Security Awareness Month of Ghana in 2019.

(Photo: National Cyber Security Centre)

Ongoing vigilance will be required. A Cybersecurity Act, passed by the legislature in 2020, gives security forces surveillance powers and legal authorities that worry some rights advocates. Ensuring these concerns are mitigated will depend on Ghana’s independent judiciary, a well-organized civil society, constitutional rights to freedom of expression and access to information, and strong data protection laws.

Takeaways

Ghana still faces significant cyber-related challenges. Its national cybersecurity policies can be overly ambitious at times and fail to reflect realities on the ground. For example, only 35 percent of Ghana’s banks have fully complied with the Bank of Ghana’s Cyber and Information Security Directive (largely because of onerous demands that attempt to bring Ghana’s banking sector in line with international cybersecurity standards). Even as cybersecurity in the traditional banking sector has improved, new vulnerabilities have arisen in the mobile-banking sector, where Ghana is among Africa’s leaders and regulators are struggling to catch up.

“[The case of Ghana] shows that efforts to improve cybersecurity do not have to come at the expense of democracy.”

Cybersecurity authorities in Ghana could also do more to take advantage of innovations such as anonymous threat reporting systems, that could foster further trust between public and private sector authorities by enabling private sector entities to disclose incidents with less reputational risk. And they might also take additional steps to ensure that government and security sector actors remain transparent and accountable even as they seek to promote online trust and safety.

Nevertheless, Ghana has put itself in an excellent position to limit the risks and harness the benefits of digitization. Ghana showcases how an inclusive approach to cybersecurity can lead to the development of robust, multisectoral cybersecurity institutions. It shows how these institutions are both informed by and ultimately serve to strengthen the ability of all nations to monitor, prevent, and respond to cyberattacks. Perhaps most importantly, it shows that efforts to improve cybersecurity do not have to come at the expense of democracy.

While cyber threats continue to pose significant challenges to national security, Ghana has shown how a society-wide response can effectively address them.

Kenneth Adu-Amanfoh is the Chairman of the Africa Cyber Security and Digital Rights Organization. He previously served as Director of ICT and Cybersecurity for the National Communications Authority of Ghana where he established a Cybersecurity Division and facilitated the development of Ghana’s National Cybersecurity Policy and Strategy.

Nate D.F. Allen is an Associate Professor for Security Studies for the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Additional Resources

- Nate Allen, Matthew La Lime, and Tomslin Samme-Nlar, “The Downsides of Digital Revolution: Confronting Africa’s Evolving Cyber Threats,” Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, December 2, 2022.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Mapping Disinformation in Africa,” Infographic, April 26, 2022.

- Abdul-Hakeem Ajijola and Nate D.F. Allen, “African Lessons in Cyber Strategy,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 8, 2022.

- Nathaniel Allen, “Africa’s Evolving Cyber Threats,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 19, 2021.

- Global Cyber Security Capacity Centre. “Cyber Maturity Model (CMM) Reviews from Around the World.” Oxford University, March 2022.

- International Telecommunications Union (ITU). 2020 Global Cybersecurity Index. United Nations, 2021.

- Republic of Ghana. Cybersecurity Act, 2020 (ACT 1038).

- Republic of Ghana. Ghana National Cyber Security Policy & Strategy. Ghana Ministry of Communications, July 23, 2015.