Displacement in South Sudan: A camp for internally displaced persons in Juba. (Photo: UN/Isaac Billy)

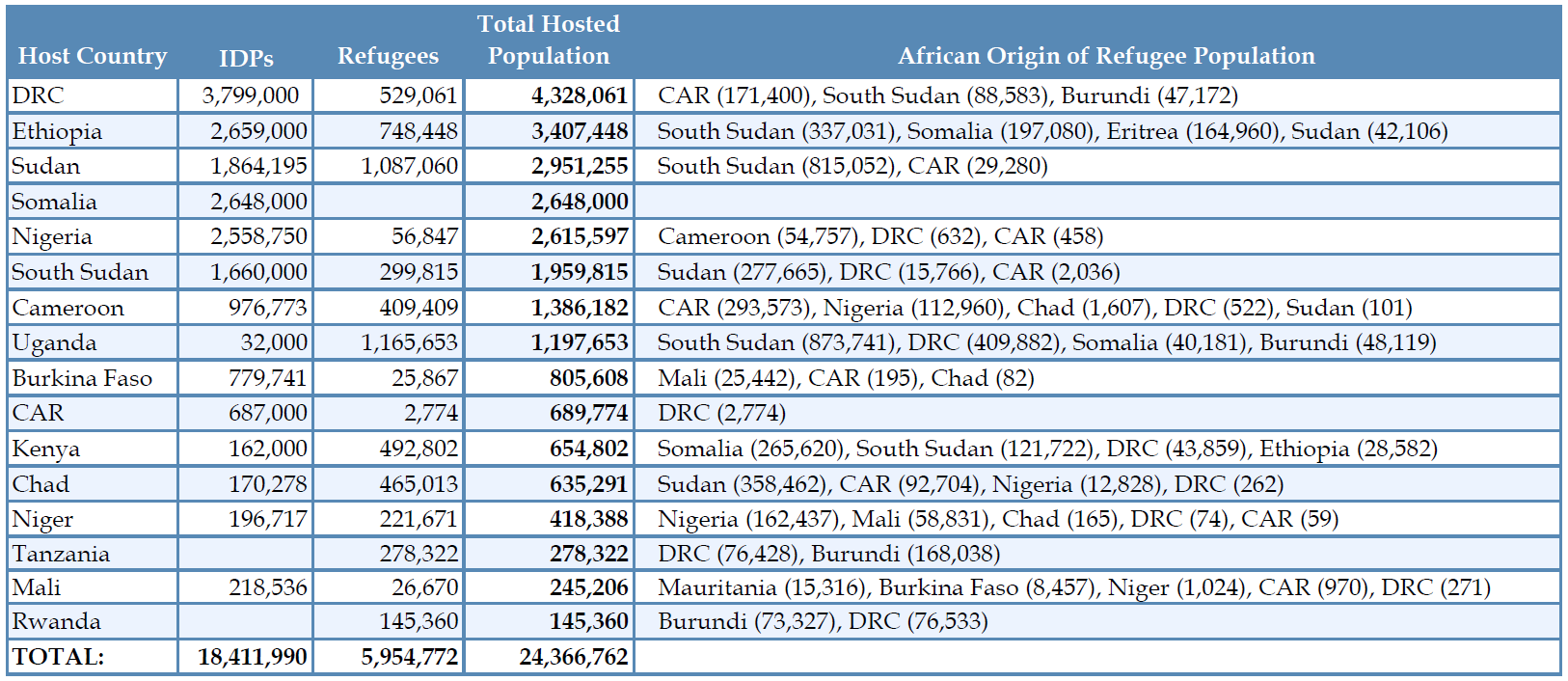

The COVID-19 pandemic is sweeping across Africa at the same time the continent is facing record numbers of population displacement. Africa currently has more than 25 million people who are forcibly displaced—internally displaced people (IDPs) and refugees—as a result of conflict and repression. Roughly 85 percent of these displaced come from eight countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), South Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan, Nigeria, the Central African Republic, and Cameroon.

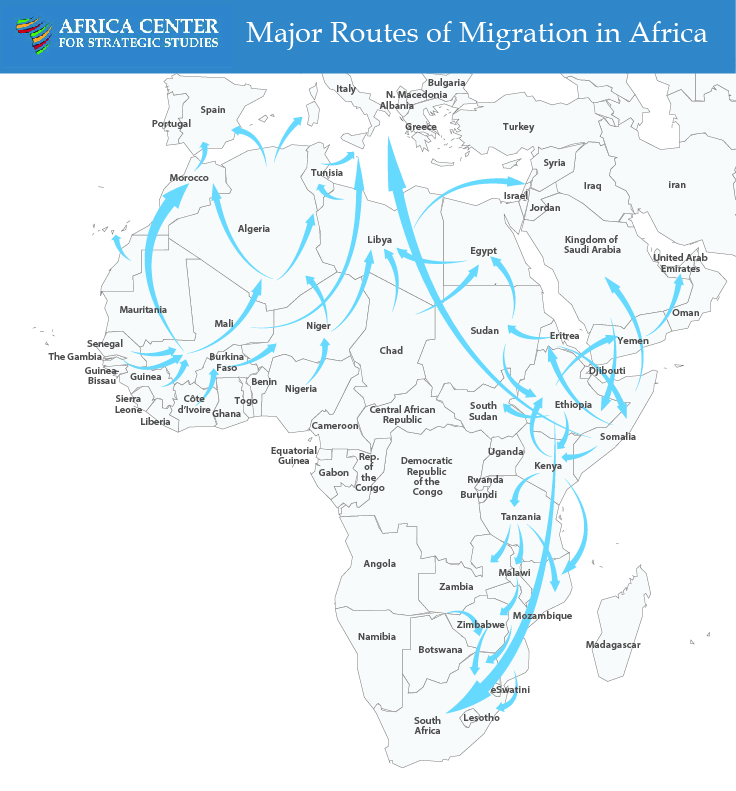

Africa is also experiencing high levels of migration—people leaving their homes in search of better opportunities—often to urban areas where there is more economic activity. Key destination countries are Algeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa. Migrants tend to travel along three main routes: from West and East Africa to North Africa, from East Africa to the Middle East, and from East Africa to Southern Africa. Roughly 80 percent of economic migrants remain in Africa.

While neither of these groups has been identified as key focal points of transmission of COVID-19, the high densities of forcibly displaced populations and the mobility of migrants make both groups highly vulnerable to exposure and therefore a priority for reducing the spread of the coronavirus in Africa. This will require informed and efficient policy engagements and public messaging, as well as the tamping down of the stigmatization and fear-based xenophobia toward these groups.

Risks Facing Africa’s Forcibly Displaced

Many of Africa’s forcibly displaced find themselves in managed camps and informal settlements of tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of people. Ten African countries host the lion’s share of displaced persons:

- Sudan hosts more than a million refugees and 1.86 million IDPs, of which 1.6 million live in camps in Darfur.

- Uganda hosts more than a million refugees. The informal Bidi Bidi settlement, the largest refugee settlement in Africa, is home to more than 230,000 South Sudanese refugees.

- More than 2 million IDPs in Nigeria have been displaced due to the Boko Haram insurgency and are living in 32 official government-run camps.

- Ethiopia hosts more than 700,000 refugees. The Gambella Region is home to more than 300,000 South Sudanese refugees in its 7 camps. Its Somali Region is host to almost 160,000 refugees from Somalia in 5 camps.

- Kenya’s 3 refugee camps in Dadaab host some 200,000 Somali refugees.

- The DRC, Chad, Cameroon, South Sudan, and Tanzania each host more than a quarter million refugees.

Many forcibly displaced populations settle into overcrowded urban areas in order to find work. In all of these environments—camps, informal settlements, shadow cities—health services are overstretched or inaccessible, increasing the risk of exposure and vulnerability to infection. The ability of these communities to practice social distancing is near impossible. If the coronavirus were to get into any of these communities, the spread would be rapid and devastating.

Many refugee and IDP camps are located in relatively isolated border areas. While this isolation offers a degree of protection, there are ample opportunities for these populations to become exposed. Government officials, aid organizations, and vendors regularly have individuals going in and out of these camps. Many within the displaced communities also travel back and forth from these settlements while looking for work, food, fuel, or water. While counseling camp inhabitants to shelter in place is good in theory, there are practical challenges to this.

Risks for Economic Migrants

The continent has a robust flow of informal migration that annually sees hundreds of thousands of people crossing borders unofficially. Most are young men and women, many seasonal and day traders, all of them traveling outside legal channels. In Africa, most informal migration is a temporary solution to a broken or undeveloped migration management system. Without some form of legal recognition, people travel at their own risk. When they cross borders for work, they remain legally, unaccounted for, and untraceable.

“If they are exposed to the virus or even get symptoms, they will most likely avoid seeking help.”

These informal migrants are drawn to economically vibrant—and densely populated—urban centers. Many of these towns and cities have overcrowded shantytowns rising up around them—lacking proper sanitation and running water—where migrants settle in with the host community’s poor. All of these residents live hand to mouth and are unable to shelter in place, much less practice social distancing.

Because they know they have no legal status, not only do informal migrants fear recognition at borders and thus shun official border crossings, they also avoid drawing attention to themselves in their everyday lives. They have not only law enforcement to fear but also the risk of violence against asylum seekers and informal migrants from local populations spurred on by fears of the pandemic. This means that if they were exposed to the virus or even get symptoms, they will most likely avoid seeking help or do anything to stand out. This, in turn, would accelerate the spread of the virus.

What Can Be Done?

The strength of the societal chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Governments must emphasize that this pandemic requires a community-wide focus on public health and human security—one that includes the most marginalized and vulnerable. This includes forcibly displaced and economic migrants, as well as the impoverished communities that host them. Stigmatization, hostility, and persecution will further spread the virus rather than stem it. Those who feel the need to hide their migrant status in order to work and live freely will also feel pressured to hide exposure to the virus or any symptoms, making themselves a threat to the entire community.

Railway tracks going through Kibera settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo: Trocaire)

In many contexts—especially in informal urban settlements and in camps—counseling good hygiene and social distancing is not enough. Adaptations are required to increase access to soap and water. Ensuring access to food and fuel to limit the need for inhabitants to travel outside camps is also needed. Fortunately, there already are some good models—from providing public services (schools, clinics, and drinking water points) in informal urban settlements, to generating public service announcements in local dialects and creating community kitchens in vulnerable areas to serve millions of meals at a time. Such models should be adapted to the context and replicated as far and wide as possible.

To date, there have been no reports of COVID-19 in African refugee and IDP camps. Nevertheless, UNHCR has put into place plans to closely monitor, report, mitigate, and respond to protection and public health risks for inhabitants of the refugee camps it manages. Such practices need to be replicated by authorities managing other displaced population settlements. Nigeria’s Borno State has banned visitors to the IDP camps it manages. Further efforts to help prevent the virus from entering the camps should be pursued. Camp administrators in cooperation with camp residents must also consider how to modify distribution logistics to prevent large gatherings, provide people with chronic health conditions backup supplies of medicine, and develop self-isolation sections to reduce intra-household and in-camp transmissions when residents do become ill.

Migrants who have settled in urban areas should be supported as part of the overall public health effort to contain and respond to the virus. Governments should also consider encouraging informal migrants to come out of the shadows to be counted, and, if necessary, tested and treated without fear of reprisal, incarceration, or deportation.

“Forcing informal migrants to stay in the shadows out of fear will only cause the virus to spread farther and faster.”

Only by identifying, isolating, and treating cases can public health leaders respond effectively to the societal threat. Forcing informal migrants to stay in the shadows out of fear will only cause the virus to spread farther and faster. Governments should also encourage migrants to remain where they are as long as they are safe. The objective should be to reduce unnecessary movements. In this way, migrants are less of a risk to themselves and host communities. Along the same lines, public messaging in countries of origin should also be ramped up to discourage new migrants from departing.

Africa faces many challenges in responding to the global pandemic. By prioritizing key vulnerable groups, like forcibly displaced and migrant populations, those involved in trying to contain the spread of COVID-19 on the continent can help flatten the curve of transmission and in the process reduce the overall impacts of the disease.

Additional Resources

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee, “Interim Guidance: Scaling-Up COVID-19 Outbreak Readiness and Response Operations in Humanitarian Situations Including Camps and Camp-Like Settings,” Version 1.1, March 2020.

- Brian Howard and Kangwook Han, “African Governments Failing in Provision of Water and Sanitation, Majority of Citizens Say,” Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 349, March 19, 2020.

- Wendy Williams, “Shifting Borders: Africa’s Displacement Crisis and Its Security Implications,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 8, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, October 17, 2019.

- Stephen Commins, “From Urban Fragility to Urban Stability,” Africa Security Brief No. 35, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 12, 2018.

More on: COVID-19 Health & Security