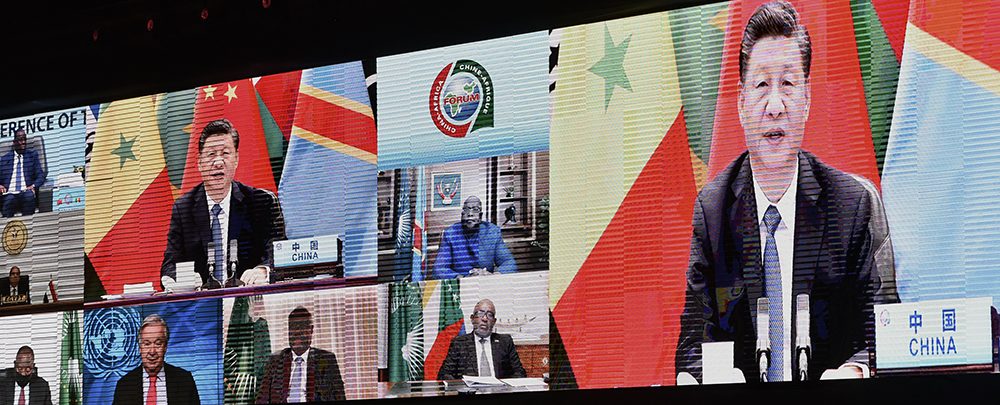

Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers his speech during the 2021 China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) meeting in Dakar, Senegal. (Photo: AFP/Seyllou)

Xi Jinping enters his third term as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong. Having evaded the two-term limit upheld by all Chinese leaders since Mao, Xi emerges from the 20th National Congress of the CCP with his protégés fully in control of the 205-seat Central Committee and its 25-seat Politburo, which includes the Politburo’s 7-member Standing Committee—China’s top leadership body.

Factions loyal to former presidents, the late Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, have no meaningful representation for the first time since 1992. Xi was named “core leader,” with near-absolute authority on policy matters. A compendium of his policy ideas, called “Xi Jinping Thought,” is codified in the party and state constitutions. The Congress reiterated the CCP’s core mission, to create a conducive environment to make China the pre-eminent global power by enhancing China’s “comprehensive national power” (zōnghé guólì, 综合国力) and “taking an active part in leading the reform of the global governance system” among other goals.

“The Congress reiterated the CCP’s core mission, to create a conducive environment to make China the pre-eminent global power.”

Africa is central to these objectives. Over the past two decades, China has mobilized African countries to provide near-unanimous support for several Chinese norms-changing resolutions in international agencies. In the UN Human Rights Commission (UNHRC), for example, African countries endorsed a Chinese-supported resolution in 2017 that put forth an alternative interpretation of human rights centered on non-interference. Similarly, all but one African member of the UNHRC supported a resolution in 2020 that inserts “Xi Jinping Thought” into UN text for the first time.

In August 2022, many African leaders reiterated their commitment to the position that “Taiwan is an inalienable part of China.” Some African governments have also supported parallel mechanisms created by China like the Asia Infrastructure Development Bank and the One Belt One Road initiative-advancing China’s efforts to create alternative international institutions while reshaping existing ones.

Compared to other regions, African countries have been more accommodating of Chinese security programs like Xi Jinping’s new and still undefined Global Security Initiative (GSI), a framework for promoting bilateral and multilateral security arrangements inspired by China’s vision of domestic and international security. African governments endorsed the GSI at the November 2021 Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) summit and the second China-Africa Peace and Security Forum in June 2022.

China’s efforts to enlist African support can be expected to intensify during Xi’s third term. The CCP views the United States as its most formidable opponent with the capacity to upend China’s grand strategy. Hence, Beijing will double down on expanding its “circle of friends” in Africa to counter the United States, validate China’s endeavors, and “preserve the power to shape,” a phrase Xi used in his political report to the National Congress.

Institutionalizing Africa Policy within the Chinese Communist Party

China’s Africa policy is highly institutionalized and managed from its most senior leaders. The Standing Committee members traditionally lead the foreign affairs organizations that interact most with African governments and stakeholders. The second most senior leader on the new Standing Committee, Li Qiang, will supervise 36 FOCAC implementing agencies when he takes over as Premier in March 2023.

Li Qiang. (Photo: China News Service)

The third most senior leader, Zhao Leji, will head the National People’s Congress (NPC), which has formal relations with 35 African parliaments. Wang Huning, the fourth most senior official in the current lineup-and an architect of FOCAC since its inception in 2000-is set to lead the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, which works with 59 political organizations in 39 African countries. In addition to these, the CCP International Liaison Department (ILD)—an arm of the Central Committee and a FOCAC implementing agent—has relations with 110 political parties in 51 African countries. Roughly two-thirds of ILD’s work globally is in Africa. The CCP United Front Work Department (UFWD) manages over 30 “front associations” in 20 African countries. As China’s premier institution for overseas influence operations, the UFWD works to engage well-placed individuals and institutions outside China to support CCP narratives, policies, and stances.

This sophisticated institutional framework serves as a standing platform for Chinese engagement in Africa. Through their auspices, senior Chinese officials visited Africa 79 times between 2008 and 2018. Between 2014 and 2020, Xi Jinping undertook 10 visits to Africa. Wang Yi, the outgoing foreign minister, visited 48 countries. Yang Jiechi, the outgoing Director of the CCP Central Foreign Affairs Commission, (and in that capacity China’s top diplomat), visited 21 African countries.

All the men on the new Standing Committee have been longtime loyal Xi aides. The same applies to Xi’s new foreign policy team. Liu Jianchao, the new director of the ILD, Liu Haixing, currently the executive director of the National Security Commission, Qi Yu, the CCP party secretary at the Foreign Ministry, and Qin Gang, currently China’s ambassador to the United States—were all handpicked by Xi. China’s next foreign minister will be selected from this cohort.

“Key Chinese governance norms include extensive party and state control over politics and society, subordination of human rights to state security, emphasis on collective rights over individual rights…”

This new foreign policy team will be supervised by outgoing Foreign Minister Wang Yi—one of the most well-known Chinese leaders in Africa—who was promoted to the Politburo as the new director of the CCP Central Foreign Affairs Commission. Wang’s new office outranks the foreign minister. His elevation will be read in Africa as an indication of continuity in China relations.

In short, China’s new crop of top leaders can be expected to build on the strong existing institutional foundation to become familiar players in Africa going forward.

The Next 5 Years

Foreign policy under Xi Jinping is more ideological than his predecessors. Xi is placing greater emphasis on instilling Chinese values and governance norms as alternatives to the West, not just increase its material power in military and economic terms. Key Chinese governance norms include extensive party and state control over politics and society, subordination of human rights to state security, emphasis on collective rights over individual rights, and a mix of market-based practices and centralized control of core economic sectors.

The 2018 Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). (Photo: AFP/Li Tao/Xinhua)

Xi has directed the CCP to “form international discourse power (huayuquan, 话语权) that matches our comprehensive national power and international status.” This is a CCP term of art that describes the ability to shape and control the narrative, key messages, and political ideas—as well as offer and build support for Chinese models as alternatives and discredit opposing ideas. This will be exhibited in Chinese foreign policy through the following channels.

First, the ILD will be more central in a largely party-driven foreign policy. ILD describes its work as exchanges and cooperation that influence attitudes and policies toward China and “make the other side understand, respect, and approve our values and policies.” In July 2022, ILD opened its first overseas political school, the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Tanzania. It received its first batch of 120 students from the former liberation movements of Southern Africa—the ruling parties of Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Such engagements—deeper and more systematic—will be more common as the CCP looks to institutionalize its influence on the ground.

Laying of the foundation stone of the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School, CCP’s first overseas political school.

(Photo: Tanzania State House)

Second, the emphasis on “discourse power” means China will make maximum use of its propaganda and media infrastructure. Since 2019, Xinhua, China Radio International, China Daily, and China Global Television Network established their African headquarters in Nairobi, and each office has local and Chinese staff. During the Fifth Forum on China-Africa Media Cooperation in August 2022, Xi Jinping called for greater “teamwork” between African and Chinese media, meaning China will be focused on promoting pro-Chinese narratives through paid content, content-sharing agreements, sponsored content, and broadcasting.

The Forum identified four areas of strengthened cooperation: program co-broadcasting, documentary creation, program innovation, and new media cooperation. Moreover, the CCP is focused on completing FOCAC’s “10,000 Villages Project”—a partnership between its publicity department, African broadcasters, and the Chinese government to expand digital television access to 10,000 African villages. It is being implemented by Beijing’s Star Times, Africa’s second-largest digital TV provider.

Finally, the CCP will reboot its “people-to-people work” after a 3-year COVID-induced freeze. Prior to this, China trained more African students and professionals than any other industrialized country, providing 50,000 academic scholarships, 50,000 training quotas for public servants, senior, and rising leaders, and 2,000 for youth annually. Most of these training opportunities are in China. Roughly 10 percent are directed at Africa’s security sector. While the new figures are unlikely to be finalized any time soon due to China’s “zero COVID” campaign, the CCP has signaled it wants to remain Africa’s most important destination for education and training.

“All indicators point to an expansion of Chinese ideological messaging in Africa under Xi Jinping’s third-term foreign policy.”

In January 2023, Africa will host the Chinese Foreign Minister’s first overseas visit of the year, maintaining a tradition for the 33rd year in a row. A few months later, roughly 60 African journalists and broadcasters will travel to China for the seventh round of 10-month media fellowships, where they will cover the first plenary sessions of the next National People’s Congress and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, slated to take place in March 2023, when the new leadership will be sworn in.

In sum, all indicators point to an expansion of Chinese ideological messaging in Africa under Xi Jinping’s third-term foreign policy. The CCP’s theory of change can be characterized as, if more partners adopt, embrace, or at a minimum see the value of Chinese perspectives, policies, norms, and models, then China will find it easier to rely on their continued support for its global ambitions.

Additional Resources

- Nosmot Gbadamosi, “What Xi’s Third Term Means for Africa,” Foreign Policy, October 26, 2022.

- Yun Sun, “Foreign Policy Personnel Under Xi’s Third Term,” Stimson Center, October 25, 2022.

- Yun Sun, “Chinese Campaigns for Political Influence in Africa,” Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, May 8, 2020.

- Paul Nantulya, “China’s Strategic Aims in Africa,” Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, May 8, 2020.

- Niel Thomas, “Proselytizing Power: The Party Wants the World to Learn from Its Experiences,” Macro Polo, January 22, 2020.

- Nadège Rolland, “China’s Vision for a New World Order,” NBR Special Report No. 83, National Bureau of Asian Research, January 20, 2020.

More on: China in Africa External Actors in Africa