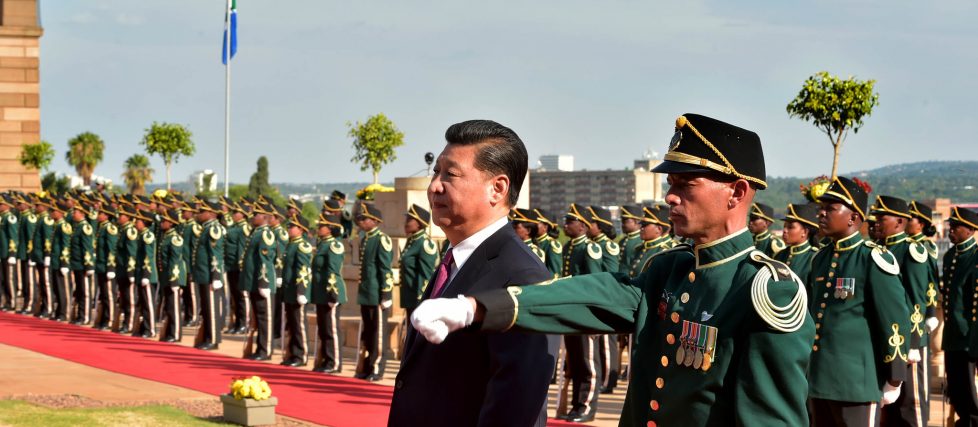

Chinese President Xi Jinping inspects the military guard of honour during his state visit to South Africa at the Union Buildings in Pretoria in 2015. (Photo: GovernmentZA)

The principle of absolute party control of the military is one of the pillars of China’s governance model. It follows the central rule—“The party commands the gun, and the gun must never be allowed to command the party” (Qiānggǎn zi lǐmiàn chū zhèngquán, 枪杆子里面出政权)—coined by the founder of the Communist Party of China (CPC), Mao Zedong. The adage defines the relationship between the ruling party and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), as well as the party’s tight control of the Chinese government, which is often described as a “party state” (dǎng guó, 黨國).

As China deepens its ties to African militaries, including through training and education initiatives, Beijing brings its perspective on party-army relations. The venues through which it does this have been growing steadily in the past decade. For example, under its China-Africa Action Plan 2018-2021, China receives 60,000 African students annually, which surpasses both the United States and United Kingdom. China provides an additional 50,000 professional training opportunities and 50,000 government fellowships to African public servants. Around 5,000 slots go to military professionals, up from 2,000 under its 2015-2018 Plan.

“The Chinese party-army model also tends to reinforce elite networks and hierarchies, which feature heavily in China’s political relationships and often supersede institutional and constitutional procedures.”

The concept of party supremacy over the military is at odds with the principle of an apolitical military, which is central to the multiparty democratic systems adopted by nearly all African constitutions since the early 1990s. The Chinese party-army model has obvious appeal to some African ruling party and military leaders who welcome redefining the role of the military as ensuring the survival of the ruling party. It also tends to reinforce elite networks and hierarchies (guānxi, 关系), which feature heavily in China’s political relationships and often supersede institutional and constitutional procedures.

China’s Party-Army Model

At the start of China’s latest phase of military restructuring in October 2013, the 18th CPC Party Congress directed the PLA to ensure “resolute obedience to the command of the CPC Central Committee.” This is accomplished through three mechanisms.

China’s leaders at the start of the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. (Photo: Remko Tanis)

First, the party Central Military Commission exercises operational control of the military under the leadership of the Politburo, the CPC’s highest organ. This Commission ranks above the Defense Ministry, which plays a consultative role. Second, the Political Work Department conducts political and ideological education across the armed forces through a network of political commissars (zhengwei, 政治委员, 政委) who hold the same rank and authority as the military commander at each level. The Political Work Department in turn sits alongside the Joint Staff and other departments working on logistics, strategic planning, and training.

“What emerges from this model is what China’s leaders call a party-army whose primary duty is the survival of the ruling party.”

Third, senior uniformed officers sit on the ruling party’s functional and leadership organs as part of the CPC’s apparatus. What emerges from this model is what China’s leaders call a party-army whose primary duty is the survival of the ruling party. While China’s military restructuring sparked some internal debate between ideological purists and those who lobbied for the PLA to transform itself into a national army (jundui guojiahua, 军队国家化), the latter argument was rebuked in a pointed article published in the Party’s flagship journal, Qiushi. The article criticized “some” that have “blindly admired” Western models “in which armies serve national goals and not those of individual parties.” If those ideas gain prominence, the article warned, “The PLA will lose its soul and thus its ability to defend the party.”

China’s Party-Army Model in the African Context

African students are exposed to the Chinese model on party-army relations at three career levels in China’s professional military education (PME) engagements. The first is the regional academies for cadets and junior officers, such as Nanjing Military Academy, Dalian Naval Academy, and the PLA Air Force Aviation University. Next, the command and staff colleges—including Army Command Colleges in Nanjing and Shijiazhuang and the Command and Staff Colleges of the PLA’s service branches—train mid-career officers. The bulk of African military students train at these two levels, a legacy of China’s role in building Africa’s newly established militaries after independence. China’s National Defense University and National University of Defense Technology are the upper tier of China’s PME, admitting more than 300 foreign officers annually, mostly from developing countries, with African officers constituting slightly under 60 percent.

Teaching Building of China’s National Defence University. (Photo: 云不会哭)

African officers also attend the PLA’s political schools, which provide training on the mechanisms China’s ruling party uses to exercise control over the military, including through the political commissar system. Angola, Algeria, Cabo Verde, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Mozambique, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe have all adopted various forms of this Maoist model of fusing the ruling party and military. The PLA political schools also provide a venue for military officers and senior civilian officials to tailor the Chinese experience in political and ideological training to their own military establishments. They include the Kunming National Cadres Academy, Pudong Cadre College, and PLA Nanjing Political College. Additionally, hundreds of “militants”—party loyalists with weapons training but no formal military ranks—have trained in these schools. Many political parties, such as Burundi’s ruling Council for the Defense of Democracy/Forces for the Defense of Democracy, use these party militants as part of their enforcement machinery.

Versions of China’s politico-military schools have been adopted in a range of African contexts, reflecting shared traditions with many of Africa’s liberation movements. They include Uganda’s Oliver Tambo Leadership Academy, a politico-military school built on the former military base of South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) during apartheid; Ethiopia’s Political School in Tatek; Namibia’s SWAPO School in Windhoek; and the ANC’s planned Political School in Venterskroon.

In 2018, the Communist Party’s International Liaison Office provided $45 million toward building the Mwalimu Nyerere Leadership Academy in Tanzania, an ideological school modeled on the Pudong Cadre College that will train civilian and military cadres from the Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa (FLMSA) once completed. Meeting at a summit every three years, FLMSA consists of the ruling liberation movements of Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, all of which were trained by the PLA during their liberation struggles. Most of them enjoy Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership Agreements with China, the highest-level partnership it can offer any foreign country.

“Many senior African military leaders reject any political role for professional African militaries.”

To be clear, many senior African military leaders reject any political role for professional African militaries. Retired Zambian Colonel Naison Ngoma contends that politicization tends to be prevalent in countries where the military and state structures are exceptionally close. Retired Colonel Émile Ouédraogo of Burkina Faso makes a similar argument, suggesting that “genuine military professionalism should be grounded in subordination of the military to democratic civilian authority, allegiance to the state, a commitment to political neutrality, and an ethical institutional culture.” Retired South African Colonel Abel Esterhuyse identifies robust civilian oversight, education, and training on constitutional roles and responsibilities as essential components in building professionalism and ensuring that soldiers do not become a political liability.

Ramifications of China’s Party-Army Model in Africa

Experience has shown that embedding the Chinese approach of integrating the military into party politics is fraught with risks. Nowhere is this more evident than in Zimbabwe.

On November 16, 2017, flanked by all 60 members of Zimbabwe’s top brass, then Chief of Defense (now Vice President) Constantine Chiwenga warned the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) about internal infighting. “It is pertinent to restate that the Zimbabwe Defense Forces remain the major stakeholder in respect to the gains of the liberation struggle and when these are threatened we are obliged to take corrective measures!” A day later, the army took control of key state institutions.

Chiwenga was more than a military chief. He once headed ZANU-PF’s Political Commissariat. Like other senior Zimbabwean officers and his Chinese counterparts, he was deeply embedded in the party’s workings. This institutional arrangement is known in ZANU-PF as “politics shall always lead the gun,” the Zimbabwean adaptation of Chinese ideological principles.

ZANU-PF’s real power came from its Political Commissariat, which was historically staffed by generals. Mugabe’s faction within ZANU-PF accused the military of violating its founding Maoist principle to listen to party commands at all times. As the infighting deepened, then President Robert Mugabe appeared to side with a faction loyal to his wife, Grace, a move many military officers who sit in the party’s top organs rejected. In the end, they unseated him and installed their preferred successor, current President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

Generals of South Sudan’s army celebrate during official independence day ceremonies.(Photo: Steve Evans)

These lessons are also borne out by the crisis in South Sudan’s ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A), which adopted many Maoist traditions. The outbreak of civil war on December 15, 2013, began as a leadership dispute between President Salva Kiir and then Vice President Riek Machar. Months of infighting foreshadowed a stormy December 13 meeting of the Politburo, the SPLM/A’s chief decision-making body, two-thirds of which consists of soldiers. The thin layer of insulation between the party and army was laid bare when the disagreements spilled into the military, which subsequently splintered into factions by December 15.

The Maoist model of party-army relations has developed and is implemented in different forms across the continent. For example, Angola’s ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola still conducts “patriotic ideological education” at all levels of the armed forces to ensure party loyalty. Angolan President João Lourenço is himself a former Political Commissar. So are Mozambique’s former presidents Joaquim Chissano and Armando Guebuza, and former Tanzanian president Jakaya Kikwete. In Mozambique, senior leaders—including the defense minister—sit on the Central Committee of the ruling Frelimo party and its inner sanctum, the Political Commission. Frelimo uses “brigades”—seasoned party and military veterans—to conduct mass political education and ensure party loyalty across the state and government. Headed by a Deputy Chief of Staff, South Sudan’s Office for Political and Moral Orientation instills the ruling SPLM ideology throughout the uniformed services, a replica of the PLA’s Political Work Department and Uganda’s Political Commissariat.

In Uganda, a Chief Political Commissar supervises political commissars across the military. The current Commissar, Brigadier General Henry Matsiko, explains that the uniqueness of Uganda’s military lies in “political clarity and having an ideology guiding the work of this mighty force.” The founders of Uganda’s ruling National Resistance Movement/Army—many of whom participated in Mozambique’s independence war—were mentored and trained by Frelimo using Maoist methods. The Ugandan government’s adoption of these models is reflected in several foundational texts of Uganda’s PME, including the book Mission to Freedom and the chapters “Why We Fought a Protracted People’s War” and “The NRA and the People” in What Is Africa’s Problem? All were authored by Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, who, during a visit to Mao Zedong’s birthplace in Hunan in June 2019, said, “Revolutionaries come to Hunan like Catholics go to Rome.”

Weaknesses of the China Model in China

China has also faced pitfalls from its model. The CPC’s Small Leading Group on National Defense and Military Reform (Zhōngyāng Jūnwěi Shēnhuà Guófáng hé Jūnduì Gǎigé Lǐngdǎo Xiǎozǔ, 中央军委深化国防和军队改革领导小组), which has supervised China’s military restructuring process, drew up a list of factors that have undermined the PLA’s cohesion and effectiveness: factions, political patronage, and corruption. These issues became embedded in the CPC and spilled into the military a result of the tight fusion between the party and armed forces.

The politicization of the military also enabled General Secretary of the CPC, Xi Jinping, to assert his personal dominance over the PLA under the guise of anticorruption initiatives. The PLA’s massive restructuring started off with a purge of over 100,000 party officials and 120 senior officers. Furthermore, new regulations were adopted to outlaw soldiers from running businesses and empower uniformed officers as opposed to party ideologues to run the PLA.

Rwandan President Kagame received by President Xi Jinping of China. (Photo: KT Press)

Despite the weaknesses, the separation of the party, military, and state is strictly off the table. In reflecting on the restructuring process, General Fang Changlong, the Vice Chairman of the CPC Central Military Commission, warned that soldiers must “resolutely refute and reject the erroneous political viewpoints of disassociating the military from the party, depoliticizing the armed forces, and putting them under the state.” General Li Jinai, the former Director of the PLA’s Political Department, similarly lambasts the idea of depoliticizing the PLA as “an attempt by domestic and foreign forces to overthrow the party.”

Conclusion

Beijing’s efforts to shape norms of the party-army model within Africa have been aided by China’s strong ideological ties with certain African countries dating back to its support for independence movements. Some African leaders argue that since Chinese models and doctrine were vital to winning independence, they are relevant to addressing Africa’s future needs. The sense of entitlement to rule by many of Africa’s liberation movements and their desire to increase their longevity in office, however, is at the heart of many of Africa’s conflicts, political crises, and stalled democratic transitions.

Even China has encountered problems from the close relationship between the party and military. Most African constitutions and military professionalism advocates, moreover, argue that professional African militaries can only be established via apolitical armed forces that are committed to serve the nation rather than a single political party. Regardless, the foundations for China’s ideological push to advance its party-army model in Africa have been laid.

Additional Resources

- Kwesi Aning and Joseph Siegle, “Assessing Attitudes of the Next Generation of African Security Sector Professionals,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 7, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 1, 2019.

- Joel Wuthnow, “China’s Other Army: The Peoples Armed Police in an Era of Reform,” China Strategic Perspectives No. 14, Institute for National Strategic Studies, April 16, 2019.

- Phillip C. Saunders, Arthur S. Ding, Andrew Scobell, Andrew N.D. Yang, and Joel Wuthnow, “Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms,” National Defense University, 2019.

- Phillip Carter III, Dr. Raymond Gilpin, and Paul Nantulya, “China in Africa: Opportunities, Challenges, and Options,” in Scott D. McDonald and Michael C. Burgoyne, China’s Global Influence: Perspectives and Recommendations, Daniel K. Inouye Asia Pacific Center for Strategic Studies, October 2019.

- Paul Nantulya, “Chinese Hard Power Supports Its Growing Strategic Interests in Africa,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 17, 2019.

- Joseph Siegle, “The Political and Security Crises in Burundi,” United States Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Africa and Global Health Policy Testimony, December 10, 2015.

- Xi Jinping, “Strengthen Cooperation for Advancing the Transformation of the Global Governance System and Jointly Promote the Lofty Task of Peace and Development for Mankind” (习近平:加强合作推动全球治理体系变革 共同促进人类和平与发展崇高事业), published by Xinhua, September 28, 2016.

- Zhang Lihua, “China’s Traditional Cultural Values and National Identity,” Window into China, Carnegie Tsinghua Center for Global Policy, November 21, 2013.

- Christopher Clapham, “From Liberation Movement to Government: Past Legacies and the Challenge of Transition in Africa,” Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, January 2013.

More on: Africa Security Trends Regional and International Security Cooperation Security Sector Governance China