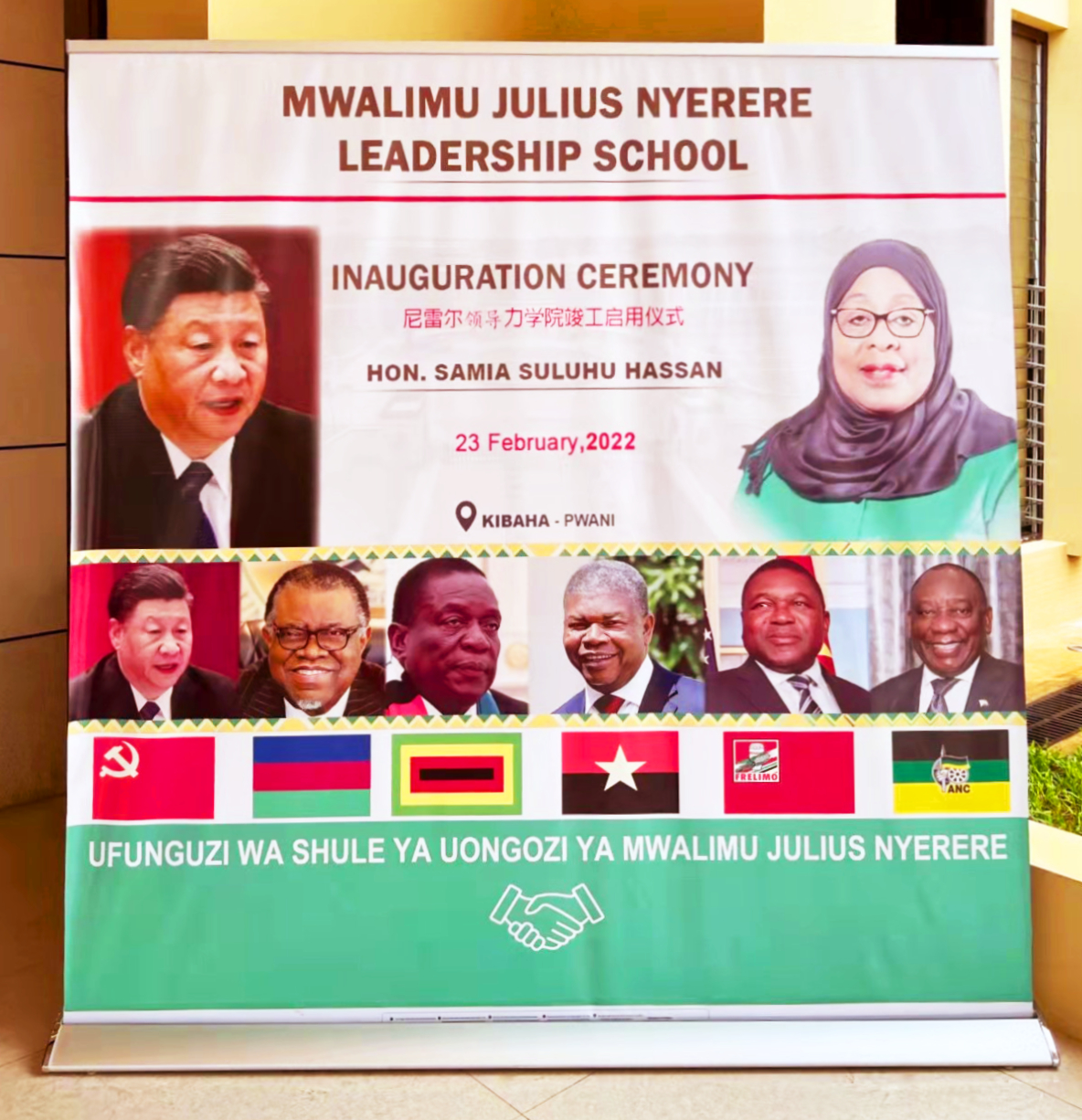

The Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Kibaha, Tanzania. (Photo: AFZ)

On February 22, 2022, the inaugural class of the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Kibaha, Tanzania, listened intently to a message from Chinese President Xi Jinping. The Chinese leader spoke of “Great Changes Unseen in a Century” (bainian weiyou de da bianju; 百年未有 的大变局) and the “urgent need for China and African countries to strengthen solidarity, common development, and exchange of Chinese experience and mutual understanding in governance.”

Named after Tanzania’s revered founding father, this School is a joint project of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and six Southern African ruling liberation movements: the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO) of Namibia, Tanzania’s Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM, or Revolutionary Party), South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC), and the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF).

These parties are part of the Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa (FLMSA) coalition, which analyzes geostrategic trends, domestic and global challenges to their rule, and plans to provide one another support. FLMSA is an incarnation of the Frontline States (FLS) alliance—a grouping of Southern African countries that gave sanctuary to guerillas fighting colonialism and apartheid. The FLMSA, in turn, is the nucleus of the 16-member Southern African Development Community (SADC).

The School underscores China’s approach to playing the long game to building influence.

China has been an ideological and military supporter of the six liberation movements and is now the sole external partner of FLMSA. China also provides more professional military education (PME) opportunities to SADC than other African regions. The Nyerere Leadership School reinforces this strategic partnership. It enables the six FLMSA parties to lay plans more systematically using training, educational, residential, and sporting facilities gifted to them by the CCP’s Central Party School in Beijing through a $40 million grant.

This School has prompted widespread debate in Southern Africa and beyond. While its members led their countries to independence, they have also exhibited tendencies that undermined democracy and constitutionalism. While they all ostensibly adhere to multiparty political systems, many have been largely intolerant of opposition challenges and have employed wide ranging measures to stifle, constrain, and even dismantle opposition parties.

Fraudulent elections, electoral violence, and grand corruption have become widespread under their watch, along with the erosion of democratic institutions. Ibbo Mandaza, a renowned stalwart in the Southern African liberation movements, observed that many liberation parties were afflicted by “pathologies of militarism over politics, brute force to instill conformity, witch hunting, abuse of women and vulnerable groups and other ills that were carried into government, breeding impunity, and disdain for national institutions and accountability.”

There has yet to be an interparty transition of power in any of the FLMSA countries decades since independence. In effect, in many post-liberation settings, one-party rule is perpetuated within increasingly lopsided multiparty arrangements.

A poster displaying FLMSA member heads of state at the School’s inauguration. (Photo: AFZ)

Given the School’s mission of strengthening the incumbency of liberation parties, they face a quandary when one of their members fall short of democratic standards as was the case in Zimbabwe’s disputed August 2023 elections. The six FLMSA parties sent their own observer missions to Zimbabwe alongside the SADC observers. Tellingly, none made their reports public. They preferred to shield their fellow member, the ZANU-PF, from accountability. This, even though the SADC Electoral Observer Mission concluded that the polls were riddled with widespread irregularities.

ZANU-PF leaders trashed the SADC report and hurled insults at the head of this mission (former Zambian Vice President Nevers Mumba) and at Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema, who chairs the SADC Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation. ZANU-PF spokesman, Chris Mutsvangwa, called President Hichilema a “puppet” who “did not participate in the liberation struggle” and who was among “those who wanted to see the back of liberation movements.” In his view, those who did not participate in the armed struggle had no right to govern, much less criticize ZANU-PF.

Tanzania’s founding father, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, modeled the exact opposite sentiment toward governance. While acknowledging his mistakes, he espoused principles and practices of tolerance, frugality, fidelity to human rights, nonviolence, and constitutionalism. He famously accused the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union, or AU) of being a trade union of leaders that defend one another at all costs. “We should be able to talk more openly about human rights within our own territories,” he said.

Nyerere voluntarily left office in 1985. He used his retirement to shepherd Tanzania toward multiparty politics and to mediate peace in the region. In one of his books titled Our Leadership and the Destiny of Tanzania, Nyerere maintained that participation in a liberation struggle does not bestow on one the legitimacy to rule indefinitely, or for life, or mean that those who did not participate in these struggles had no right to govern.

The FLMSA’s Leadership School rightly extols the image of Nyerere as a nationalist, pan-Africanist, and liberation hero. However, his liberation project was inseparable from his philosophy and practice of political morality and ethics, summarized as Ubuntu and Utu (“I am because you are” or “humanity to others.”) This aspect of Nyerere’s legacy appears to have been co-opted in favor of regime survival at all costs, which he clearly stood against.

Striving for “Stability Maintenance” (weiwen; 维稳)

The six FLMSA parties are focused on supporting one another to preserve their rule against perceived threats. The CCP term for this is weiwen (维稳), meaning “stability maintenance” or “regime survival” under CCP rule. The 2017 FLMSA summit adopted a document, “War with the West,” that accuses former colonial powers and the United States of seeking regime change through “color revolutions,” financing opposition challengers, and even coup plots. It also acknowledges that liberation parties are losing popularity and at risk of losing power, decries “ideological bankruptcy” and general “lack of discipline” among members, and the tendency by the so-called “born free” generations to vote for other parties.

The 2017 summit concluded that a joint political school for ideology was needed to instill vigilance against such threats. It would provide “strong ideological grounding” for party cadres along with a series of “tough disciplinary measures” to be undertaken by sister parties. Tanzania was chosen as a venue for the school given its role in hosting all liberation movements recognized by the Organization of African Unity.

The CCP’s governance model is emerging as one of the maneuvers being employed to rig multiparty systems to cling to power.

By supporting the project, the CCP capitalized on an opportunity to relocate some of its political and ideological programs to Africa. The Nyerere Leadership School is the first political school the CCP has built overseas, a bold move by a party that often denies that it promotes its political system abroad. The School enables the CCP to proselytize and methodically share its governance model. Political theoreticians from the CCP’s Central Party School in Beijing have been deployed to the School as instructors.

Speaking at the School’s cadre development seminar in March 2022, the Secretary General of Tanzania’s ruling CCM, Daniel Chongolo, said that the six FLMSA parties “cherish their traditional friendship with the [CCP], and wholeheartedly admire the remarkable achievements China has made under the leadership of the [CCP] Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping as the core.” He went on to declare that the FLMSA “hoped to learn [from the CCP’s] experience in developing [the] economy, creating jobs, scientific and technological innovation, environmental protection, and fighting corruption.”

At a follow-up course for young leaders, School Principal Marcellina Chijoriga said that the six parties had seen how “China has developed over the decade, which shows the world that their development paths are working. Strong leadership has been a major factor contributing to economic success.” “They [CCP] are working hand in hand [with the government],” noted Collin Ngujapeua, a senior official of Namibia’s ruling SWAPO party. “That’s one of the very important aspects that we need also to work on in Namibia and also in other African sister parties.”

By using the term, “working hand in hand,” Ngujapeua was referring to the CCP’s founding principle of “absolute party control of government,” or the “one post two responsibilities system” (yi gang shuang ze; 一岗双 责). This approach to governance harkens back to the era of de facto and de jure single-party rule in Africa. The model is regaining popularity among some African ruling parties. It is emerging as one of the maneuvers being employed to rig multiparty systems to cling to power.

Political Kinship, Strengthened Bonds, and a United Front

As like-minded parties, the FLMSA and the CCP can be said to form a “United Front” (tongyi zhanxian; 统一战线)—a Chinese strategy that mobilizes support outside the CCP and around the world to advance China’s interests and isolate its adversaries. As part of a larger United Front, the School syllabus gives priority to synthesizing the CCP’s overall experience to local conditions. This is what FLMSA and CCP officials mean when they say, “strengthening the sharing of experience in political governance.”

The CCP’s Central Party School is not just a funder but is an active stakeholder and participant in the School’s operations through its instructors, other CCP officials, the Chinese embassy, and the Centre for Chinese Studies at the University of Dar es Salaam, which is co-located at the Confucius Institute. The CCP emblem is included in all the School’s official communications along with the insignia of the six FLMSA parties. The CCP flag flies alongside those of the other six parties at the entrance of the School.

The Chinese flag flies alongside those of FLMSA member states outside the entrance to the Nyerere Leadership School. (Photo: screen capture)

The CCP hopes to gain a return on investment as the School gives it a permanent home for year-round interactions with each party’s new recruits and senior party cadres. This puts it in an advantageous position to shape the African liberation parties’ China friendly policies and long-term influence.

Students at the School study the history of their liberation struggles, the CCP and Chinese experience, and the current state of liberation parties. Party recruitment, management, administration, mass mobilization, leadership, and propaganda systems are also taught with the help of CCP resource persons.

The training also covers closer policy coordination on international issues. This is a key element of the United Front between China and its partners. Since 2016, countries governed by the FLMSA alliance and the rest of SADC have been part of the 39 African countries that have directly or indirectly backed China’s expansive and extralegal territorial claims in the South China Sea rather than abide by the 2016 ruling of the international tribunal under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. African coalitions have similarly defended China at the UN Human Rights Council when proposals were tabled to investigate its human rights situation. In exchange, China rallied to defend them when their own human rights issues came up for debate.

An Attempt to Appropriate the Nyerere Legacy

The regime-centric orientation of the School diverges with the agenda of other leadership institutes bearing the name of Mwalimu Nyerere. The Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation (MNF)—the official repository of his works—strives to build inclusive democracy, social justice, and a culture of tolerance through training, capacity building, and high-level mediation. Through the Mwalimu Nyerere Pan-African Young Leaders Fellowship Program, the MNF mentors rising African leaders to model Nyerere’s leadership style and improve the quality of democracy in their home countries.

Nyerere maintained that participation in a liberation struggle does not bestow on one the legitimacy to rule indefinitely.

The Mwalimu Nyerere Memorial Academy offers a similar program through a 4-year degree program focused on ethical leadership. The Julius Nyerere Leadership Centre at Uganda’s Makerere University focusses on using the Nyerere tenets to build servant leadership and democratic governance among student leaders.

The FLMSA’s Nyerere Leadership School has a vastly different focus. At the June 2023 graduation ceremony attended by top CCP and FLMSA leaders, Richard Kasesela, a former senior Tanzanian official, spoke about the upcoming SADC polls. “If we don’t win them, there will be no liberation movements to talk of. For now, we should help ZANU [Zimbabwe] win its elections. ANC [South Africa] and SWAPO [Namibia] go for elections next year and CCM [Tanzania] in 2025. We need to put together plans to help each other win these elections.” Accordingly, ZANU-PF could count on the support of its colleagues even after SADC concluded that the Zimbabwe elections were fraudulent.

Southern African civil society organizations and local Zimbabwean electoral observers have called this “negative solidarity.” This refers to the tendency of liberation parties to defend one other instead of upholding the AU’s African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance or for the parties to hold themselves accountable in line with the AU’s African Peer Review Mechanism.

“Negative solidarity”: the tendency of liberation parties to defend one other instead of upholding democratic norms.

The FLMSA’s School underscores China’s approach to playing the long game to building influence, in this case through a permanent space where it can prepare cohorts from among the most influential countries in SADC and the AU. It is likely that the School will soon open its doors to other ruling parties.

Some make the case that political party capacity building is not inherently problematic. However, it takes on an entirely different purpose when it focuses on regime protection and survival, and only targets ruling parties as the FLMSA project appears to do.

Ruling parties that emerged from armed struggle have tended to develop a strong culture of entitlement. Yet successful liberations do not guarantee successful political transitions. Recognizing the limits of legitimacy deriving from armed struggle is key. As longtime Africa scholar Christopher Clapham observes, the moment soon arrives when such a regime “is judged not by promises but by performance, and if it has merely entrenched itself in positions of privilege reminiscent of its ousted predecessor, that judgment is likely to be a harsh one.”

Additional Resources

- Paul Nantulya, “SADC Attempts to Navigate Zimbabwe’s Disputed Election,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, October 11, 2023.

- Ibbo Mandaza, “State of Democracy in the SADC Region,” Lecture at the ANC’s Oliver Tambo School, September 28, 2023.

- Patrick Gathara, “What Went Wrong with African Liberation,?” Al Jazeera, September 9, 2019

- Peter Fabricius, “When ‘Democracy’ becomes ‘Regime Change,’” ISS Today, December 15, 2017.

- Paul Nantulya, “The Troubled Democratic Transitions of African Liberation Movements,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 14, 2017.

- SABC News, “18th Steve Biko Memorial Lecture Delivered by Ibbo Mandaza,” video, November 9, 2017.

- Alex Vines, “Are Southern Africa’s Liberation Movements in Crisis?” Newsweek,August 16, 2016.

- Keith Somerville, “From Liberation to Liability: The Record of National Liberation Movements in Southern Africa,” African Arguments, August 5, 2013.

- Christopher Clapham, “From Liberation Movement to Government: Past Legacies and the Challenge of Transition in Africa,” KAS International Reports, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, February 2013.

- Joseph Siegle, “Building Democratic Accountability in Areas of Limited Statehood,” paper presented at the International Studies Association Annual Conference, March 27, 2012.

More on: China in Africa