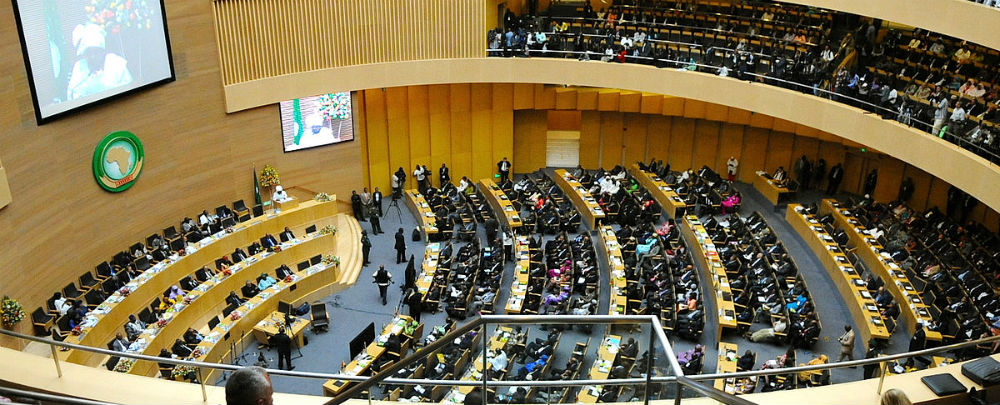

The African Union in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Among the range of conflict mitigation activities—early warning, peacekeeping, peace enforcement, peacebuilding—preventive efforts have long been at the core of the African Union’s agenda.

The Panel of the Wise is the AU’s most high-profile structure for preventing conflict, conducting on-the-ground fact-finding, presenting policy options, and brokering agreements. It is composed of five “highly respected African personalities who employ their experience and moral persuasion to foster peace” and who represent each of Africa’s five regions. It has undertaken several missions since it was established in 2007, when it hosted talks between rebels and then-president Françoise Bozizé of the Central African Republic in 2007. Among subsequent initiatives, the Panel of the Wise brokered a truce between President Joseph Kabila and opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi after heated elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo, facilitated talks between Sudan and South Sudan on post-referendum arrangements, and assisted stakeholders in drafting the “Somalia End of Transition Roadmap.” To achieve these ends, the Panel draws heavily on regional bodies including the Economic Community of West African States’ Council of the Wise, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development’s Mediation Contact Group, the Common Market for East and Southern Africa’s Committee of Elders, and the Southern African Development Community’s Mediation Reference Group.

Africa’s Conflict Mediation Panels

| African Union | Panel of the Wise |

| ECOWAS | Council of the Wise |

| IGAD | Mediation Contact Group |

| COMESA | Committee of Elders |

| SADC | Mediation Reference Group |

The AU’s conflict prevention efforts make use of additional mechanisms including calling on the participation of people of influence, conducting summit diplomacy, informal and ad-hoc mediation, and using professional mediation secretariats. Frequently, these tools are used simultaneously and feature significant improvisation, which results in complexity in both timing and practice. It also blurs the distinction between the theory and practice of conflict prevention and conflict management as illustrated by the AU’s handling of the Kenyan post-election crisis of 2008 and the mediation of South Sudan’s civil war, which broke out in 2013.

The Elders and Kenya

In the violent aftermath of Kenya’s disputed elections of December 2007, the Panel of the Wise coordinated closely with an informal but intensive conflict prevention process steered by the Elders, an independent group of retired leaders founded by Nelson Mandela to promote peace and human rights. This hybrid effort was led by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, the former first lady of Mozambique and South Africa, Graça Machel, and Benjamin Mkapa, a former president of Tanzania.

They were joined by two members of the Panel of the Wise, former presidents Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia and Mozambique’s Joachim Chissano. The moral integrity of those involved proved critical, as the parties accepted the authority of the mediation—although begrudgingly at times.

Kofi Annan. Photo: UN/Jean-Marc Ferré

Said Kofi Annan, “I came in at a time when there was so much distrust. The two sides had dug in. One side felt they won the elections fair and square, and the other maintained, ‘you stole it’.” To remind protagonists of the consequences of intransigence and draw attention to the conflict’s human cost, Machel made highly publicized visits to IDP camps. Annan made a vow before the media to “be here as long as it takes” and “pay the price of staying until we resolve this.” Reinforcing these informal, yet insistent efforts, were other initiatives including high-level visits by, among others, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and former ANC negotiator, Cyril Ramaphosa (currently South Africa’s deputy president).

Notably, the Elders took the lead in the Kenya mediation, while structures played a supportive role—with the full backing of the AU. As stated in its official account of the Panel of the Wise’s history, the AU recognized the value of informal tools, in particular because they bring the flexibility required to intervene quickly and discreetly, while also taking the local context into account.

Summit Diplomacy and South Sudan

In South Sudan, formal mechanisms took the lead when a leadership dispute in the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) turned violent and ultimately spread to the military and took on ethnic lines. A few weeks into the crisis, the AU mandated that the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) would take charge of the process, which eventually resulted in the 2015 Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan. IGAD had strong institutional memory and knowledge of the parties, having previously overseen the multiyear negotiations leading to the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the Government of Sudan and the SPLM.

As formal IGAD talks got underway, Tanzania’s ruling CCM party, with support from South Africa’s ANC, brought the three SPLM factions into an informal process to address its leadership dispute. This led to the January 2015 Agreement on Reunification of the SPLM. Although mediated separately and informally, IGAD had designed this approach to strengthen the formal talks. While the parties accepted the authority of this hybrid process, they remained deeply divided, as both tracks were often stalled by ceasefire violations and delays. However, the use of informal intra-party talks to augment IGAD’s formal negotiations was a novel technique.

IGAD representatives and others attend the first meeting of South Sudan’s Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Committee in November 2015. Photo: UNMISS.

Key Lessons

The Kenyan process confirmed the value that the moral integrity of mediators can bring. In one session, when an opposition negotiator shouted, “You stole the election,” and the government shot back, “We won it fair and square,” Graça Machel interjected, “Then why the violence? Why the swearing-in ceremony at the State House at night?” Then, as the room fell silent, she warned, “Your country is bleeding, and you need to act.”

As one observer noted, “At a time when Kenya’s angry ‘young Turks’ were whipping up the emotions that fed violence, these African elders had the calming influence of a stern grandparent.” In the end they formed a coalition government and protracted violence was averted—an outcome that would have been unlikely without AU engagement.

In South Sudan, distrust still runs deep and future fractures remain a risk. However, the South Sudan Council of Churches, drawing on its peacemaking experience, is using discreet mediation to safeguard the agreement and avoid a return to conflict. Furthermore, 28 representatives from civil society, religious leaders, former political detainees, and opposition party officials have been included in the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission, the body responsible for monitoring the implementation of the agreement. That lesson was drawn from Kenya, as the Elders worked closely with Kenya’s Citizens Coalition for Peace, an informal group of retired diplomats, generals, and religious leaders formed at the outset of violence.

In South Sudan, distrust still runs deep and future fractures remain a risk. However, the South Sudan Council of Churches, drawing on its peacemaking experience, is using discreet mediation to safeguard the agreement and avoid a return to conflict. Furthermore, 28 representatives from civil society, religious leaders, former political detainees, and opposition party officials have been included in the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission, the body responsible for monitoring the implementation of the agreement. That lesson was drawn from Kenya, as the Elders worked closely with Kenya’s Citizens Coalition for Peace, an informal group of retired diplomats, generals, and religious leaders formed at the outset of violence.

These illustrations demonstrate that moral suasion by engaged African leaders and regional backing can be key to influencing behavior change among protagonists. While the approach varies in each case depending on the type of conflict, temperament of the parties, and background of the mediators, the region’s institutional efforts at conflict prevention and mediation have proved instrumental at realizing negotiated settlements.

Additional Resources

- Ernest E. Uwazie, “Alternative Dispute Resolution in Africa: Preventing Conflict and Enhancing Stability,” Africa Security Brief No. 16, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, November 2011.

- George Wachira, “Citizens in Action: Making Peace in the Post-Election Crisis in Kenya,” Nairobi Peace Initiative Africa, January 2010.

- Scott Baldauf, “Africa’s Elders Seize a Leading Role,” The Christian Science Monitor, August 5, 2008.

- Elisabeth Lindenmayer and Josie Lianna Kaye, “A Choice for Peace? The Story of Forty-One Days of Mediation in Kenya,” International Peace Institute, August 2009.

- Jérôme Tubiana, “Civil Society and the South Sudan Crisis,” International Crisis Group, blog post, July 14, 2014.

- International Crisis Group, “South Sudan: A Civil War by Another Name,” Africa Report No. 217, April 10, 2014.

- Laurie Nathan, “Mediation and the African Union’s Panel of the Wise,” Discussion Paper No. 10, Crisis States Research Center, June 2005.

- African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), “The African Union Panel of the Wise: Strengthening Relations with Similar Regional Mechanisms,” Report of the High Level Retreat of the African Union Panel of the Wise, June 4–5, 2012

More on: Conflict Prevention or Mitigation African Union Mediation