A Fulani man herds cattle in northern Cameroon. Photo: Philou.cn.

In January 2013, Hamadou Kouffa led Islamist forces from northern Mali south toward Konna and Diabaly, an act that precipitated an African and French intervention eventually driving the militants out of entrenched positions. Two years later, Kouffa reemerged on the international scene at the head of the newly founded Macina Liberation Front (Front de Libération du Macina, FLM). Since January 2015, Kouffa’s group has claimed responsibility for several attacks in central Mali, including assassinations of local political figures and security forces, as well as the destruction of an ‘idolatrous’ mausoleum.

In its goals and methods, FLM resembles other Islamist terrorists operating in the Sahel and Sahara, such as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). What makes the FLM different is the attempt to rally nomadic Fulani herdsmen to its cause. Kouffa, a Fulani marabout, communicates to FLM members in the Fulani language, and the name Macina harkens back to a nineteenth-century Fulani state based in central Mali and governed under Islamic law.

The FLM strategy is potentially extremely destabilizing because it risks fusing Islamist terrorism in the Sahel with pastoralist grievances and communitarian violence. Mobilizing wider pastoralist communities like the Fulani for an Islamist agenda, as Kouffa is trying to do, would give terrorists traction among deep-seated societies that cover wide expanses of territory. It would thus confer a new ferocity, persistence, and reach upon terrorism in Africa.

Conflict between Fulani herdsmen and farmer populations has a long and brutal history in West Africa that considerably predates the subregion’s terrorist challenges. Since 2001, thousands of people have died in pastoralist-related violence. In early 2001, 913 people in Jos, Nigeria, died in Fulani herdsman–farmer violence in just a few days. Such killings have occasionally involved atrocities and desecrations.

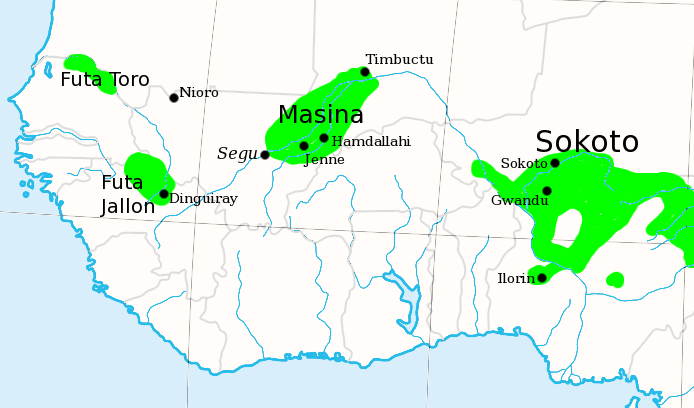

The Fulani Jihad States of West Africa, c. 1830.

The structures behind this fanatical violence are deeply rooted and politically entrenched. Nigeria’s government has conferred preferential land rights on those they dubbed indigene (native) to a region, thereby marginalizing and frustrating any so-called settler (foreign) groups, which occasionally includes the nomadic Fulani. Political elites have then manipulated such laws, rallying supporters to protect indigene status or stoking settler resentments for votes. In Mali, a 2001 Pastoral Charter has empowered local authorities to resolve land disputes. However, they can be partial to the farmers who compose the stationary constituents of well-defined territorial jurisdictions, a logic that tends to reinforce the farmers’ grip on both the land and the political system over time.

While herder-farmer tensions will undoubtedly persist in Africa, they will be worsened through association with terrorists who actively aggravate hostilities and manipulate ethnic and religious differences attached to the two lifestyles.

Pastoralist-farmer grievances are common across Africa. In many cases, these tensions are deepened by Muslim-Christian divisions. By making inroads with the Fulani, the FLM is targeting one of Africa’s largest ethnic groups, a primarily cattle-raising community of some 20 million people spread across nearly 20 nations in West and Central Africa. In addition to the Fulani, other African Muslim pastoralists are currently facing a terrorist challenge in areas such as the Sahel, the Lake Chad Basin, and the Horn of Africa. Northern Kenya is home to several herder communities, including the Turkana and Pokot, whose clashes with neighboring communities are becoming more violent through increased gun trafficking. Uganda and South Sudan have seen pastoralist violence as well. In one 2008 poll, almost half of respondents living along the South Sudan–Kenya border region had witnessed at least one violent event.1

Peul herders in Mali. Photo: KaTeznik.

General pastoralist grievances and conflicts could facilitate terrorism’s push into new areas. Islamist terrorists might mobilize herder communities in order to penetrate the Central African Republic and accelerate religious elements of that conflict. They also might exploit pastoralist tensions to extend their influence into Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. As desertification and drought displace transhumance zones, new conflicts over water and land could provide terrorist groups further opportunities to make inroads.

While herder-farmer tensions will undoubtedly persist in Africa, they will be worsened through association with terrorists who actively aggravate hostilities and manipulate ethnic and religious differences attached to the two lifestyles. To counter the FLM’s ploy, African and international authorities and communities of interest should endeavor to unite African farmers and herders against their common enemy. It should be recalled that pastoralists too have been victimized by terrorists. Boko Haram has not only raided farms for food, it has attacked herders to take livestock. Cattle markets have been destroyed, devastating pastoralist livelihoods, and breeders associations report losing thousands of lives and hundreds of thousands of animals to the conflict. And Boko Haram exploits communitarian tensions, reportedly disguising its members as Fulani herdsmen in order to escape detection and move into new areas, then conducting attacks that intensify herder-farmer hatred and instability.

A Fulani boy in Niger herds his family’s animals. Photo: ILRI.

Uniting herders and farmers against terrorism will require intentional efforts to defuse tensions between the two communities. Journalists and writers should think twice before publishing inflammatory accounts vilifying pastoralists as ‘herdsmen from Hades’ who continue or extend Boko Haram terrorism. Such coverage exacerbates community enmity and ultimately serves the FLM strategy. Fulani advocacy groups should openly denounce terrorism and should not themselves be tarnished as ‘terrorists’ for attempts to voice grievances and campaign for pastoralists’ rights. Terrorism researchers and scholars ought to reconsider tracking the Fulani-perpetrated violence within herder-farmer conflicts as acts of terrorism, a methodology that can lead to misleading analysis that casts ‘Fulani militants’ as one of the world’s top five terrorist organizations, in a class with the Islamic State, Al Shabaab, the Taliban, and Boko Haram.

Pastoralists are not terrorists. While Kouffa and other militant Islamists have aims to tap into these time-honored communities, journalists, scholars, and policy makers should work to underscore the distinction and reinforce the separation.

Note

- ⇑ Jonah Leff, “Pastoralists at War: Violence and Security in the Kenya-Sudan-Uganda Border Region,” International Journal of Conflict and Violence, Vol. 3: No. 2, 2009, pp. 188–203, 191.

Africa Center Expert

Benjamin Nickels, Associate Professor of Transnational Threats and Counterterrorism

Additional Resources

- Abdisaid M. Ali, “Islamist Extremism in East Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 32, August 9, 2016.

- Michael Olufemi Sodipo, “Mitigating Radicalism in Northern Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 26, August 31, 2013.

- Terje Østebø, “Islamic Militancy in Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 23, November 30, 2012.

- Chris Kwaja, “Nigeria’s Pernicious Drivers of Ethno-Religious Conflict,” Africa Security Brief No. 14, July 31, 2011.

- Clement Mweyang Aapenguo, “Misinterpreting Ethnic Conflicts in Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 4, April 30, 2010.

More on: Countering Violent Extremism Boko Haram Nigeria Sahel