Level of Peace:

Medium

Population:

8600000

Freedom Score:

42

Land Area:

54385

GDP (Current):

8000000000

Coastline:

56

GDP Per Capita:

918

Terrain:

Savanna in north, central hills, southern plateau, low coastal plain with extensive lagoons and marshes

Security Partners:

France, Turkey, United StatesArms Suppliers:

France, Russia, Turkey, United StatesKey Security Issues:

civil unrest, illicit trafficking, piracy, terrorism

All Security Forces

Military Expenditures

Security Forces: Total Personnel:

36500

Security Forces: Percentage:

0.6

Military Expenditure: Total:

358000000

Military Expenditure: Percentage:

17.5

Summary

Togo faces multiple security threats including violent extremist groups from the Sahel, illicit trafficking, civil unrest, and piracy. These threats are concentrated in different geographic regions of the country. Violent extremist groups operate across the northern borders with Burkina Faso and increasingly northern Benin. Civil unrest presents a greater threat in Togo’s urban centers especially near the coast and capital city, Lomé, which also serves as a significant port which attracts trafficking syndicates.

Civil unrest has periodically erupted to challenge the decades of authoritarian rule under the Gnassingbé family. The security forces are closely linked to the regime. Faure Essozimna Gnassingbé was appointed president by the military in 2005 upon the death of his father, General Gnassingbé Eyadema, who had served as president for 36 years. In 2017, opposition leaders and protesters began taking to the streets to demand that term limits, which had been eliminated in 1992, be reinstated and that President Gnassingbé resign. In 2018, the regime canceled a planned referendum that would have reinstated term limits. The canceled referendum sparked additional protests and civil unrest. In response to the canceled referendum, the opposition boycotted legislative elections held in December 2018. Bowing to popular pressures, the legislature introduced and passed a law in May 2019 that reinstated a two-term limit for the presidency, although it will not be applied to the incumbent. In February 2020, Faure Gnassingbé was re-elected in the first round of presidential elections that were marred by widespread fraud allegations.

Togo’s security forces score poorly across various accountability measures. The police use excessive force, prisoners face harsh and life-threatening conditions, suspects face lengthy pretrial detention, and instances of official corruption, impunity, and executive influence on the judiciary are prevalent. Accountability and press freedom are limited. Togo maintains regionally comparable force capabilities and has deployed relatively large troop contingents to UN peacekeeping efforts in Mali and Darfur until those missions closed. While the resources expended for its security forces have increased since 2018, they remain low when compared to other West African countries.

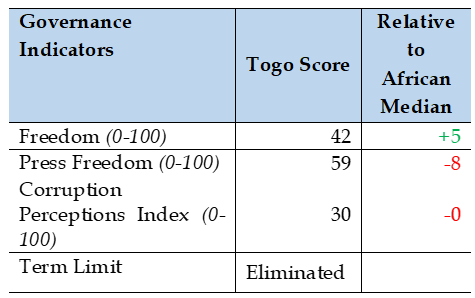

Accountability

The Gnassingbé regime in Togo limits security sector accountability. The security sector is deeply linked to the regime after more than fifty years under the rule of one family.

The Gnassingbé regime in Togo limits security sector accountability. The security sector is deeply linked to the regime after more than fifty years under the rule of one family.

While trust in Army and police rose from 42 percent in 2017 to 55 percent in 2022, trust in the president decreased from 53 percent in 2014 to 48 percent in 2022, according to Afrobarometer surveys. Trust in parliament remained relatively stable at around 40 percent. Asked about corruption in 2022, fewer than 10 percent said the president and the national assembly were not corrupt and fewer than five percent said the police were honest. Moreover, 40 percent said corruption had increased during the previous year and 84 percent said they risked retaliation for reporting corruption. Togo ranks 130th out of 180 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception.

In May 2020, newly promoted Brigadier General Tassounti Djato became chief of the general staff, replacing Felix Kadangha, who was suspected of being involved in the murder of Lt. Col. Bitala Madjoulba. In December 2022, the president fired the minister of defense and announced the role would revert to the office of the president. The president created a military tribunal and a military appeals court and named civilians to serve as top judges in both courts in February 2023. While the creation of such courts had long been called for by members of the opposition, it remained unclear on what cases the courts would have jurisdiction, and whether this would include cases that preceded its creation.

Press freedom has dropped 23 points since 2016 in VDEM’s Press Freedom indicator. Media advocates have expressed concern about a law that imposes penalties on journalists that commit “serious errors.” Security forces sometimes detain reporters without charge, delete data from their cameras and other devices, and threaten them for covering citizen protests. The regime has also reportedly bribed journalists to provide positive coverage. Journalists and media outlets face harassment, arbitrary suspensions, detention, and arrest. Journalists are periodically accused of libel, offense to the state, and defamation of officials for reporting on government authorities. Journalists report that they have been barred from working in the northern areas under a state of emergency due to the threat of violent extremism.

Leaders of the political opposition face similar forms of harassment. Authorities briefly detained Agbéyomé Kodjo for claiming the 2020 elections result were fraudulent. He was released only to face the issuance of an international arrest warrant when he persisted in his claims of fraud. In November 2020, two leading opposition members, Brigitte Adjamagbo-Johnson and Gerard Djossou were arrested for several weeks on charges of undermining the internal security of the state. Opposition groups claimed around 100 of their members were detained as political prisoners during the electoral period.

Although a Médiateur de la république (Ombudsperson) conducts investigations, the government rarely takes steps to investigate or prosecute instances of alleged human rights abuses or corruption on the part of the security forces or of government officials. Togo has a Constitutional Court, Supreme Court, Court of Appeals, Trial Courts for civil and criminal cases, and several specialized courts including a court of public accounts or Cour des Comptes, and the Court of State Security. Judiciary infrastructure is well established across the country, including in rural areas but case backlogs, ignorance of the law, and the high cost of litigation undermine access to justice.

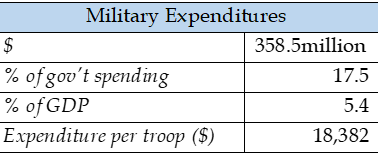

Resources

Military spending between 2012 and 2022 increased nearly 6-fold going from $65.6 to $358.5 million. Expenditures as a percent of government spending largely followed the African median from 2012 through 2016 hovering around 5.7 percent. Since 2017, however, the government has spent an increasing share of its budget on defense contributing 8.7 percent in 2017 before jumping to 17.5 percent in 2022. The president announced that the state of emergency declared in response to rising militant attacks in northern Togo will be accompanied by an increase in defense spending between 2022 and 2025 to accommodate modernizing the armed forces and recruiting new soldiers. An earlier spike in defense spending in 2019 was likely related to the organization of presidential elections in early 2020.

Military spending between 2012 and 2022 increased nearly 6-fold going from $65.6 to $358.5 million. Expenditures as a percent of government spending largely followed the African median from 2012 through 2016 hovering around 5.7 percent. Since 2017, however, the government has spent an increasing share of its budget on defense contributing 8.7 percent in 2017 before jumping to 17.5 percent in 2022. The president announced that the state of emergency declared in response to rising militant attacks in northern Togo will be accompanied by an increase in defense spending between 2022 and 2025 to accommodate modernizing the armed forces and recruiting new soldiers. An earlier spike in defense spending in 2019 was likely related to the organization of presidential elections in early 2020.

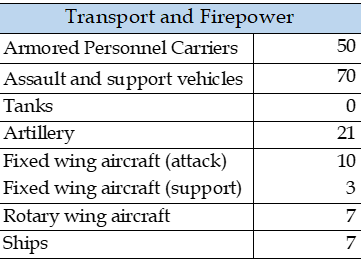

From 2012 to 2014, Togo imported $20 million in arms: $4 million in aircraft, $5 million for 30 armored vehicles, and $11 million in ships. In 2017, it signed a €20 million deal with France for four SA-342 M Gazelle light helicopters which were delivered in 2020. In November 2022, the Air Force received three Mi-35M combat helicopters and two Mi-17 transport helicopters from Russia, which partially contributed to the increase in defense spending. In 2022, Togo also received two Bayraktar TB2 armed UAVs from Turkey. Between 2020 and 2022, Togo received 100 Mamba-7 APCs in aid from the United States for troops to use in MINUSMA deployments.

Until the January 2021 passage of its first military planning law, Togo’s defense budget was not public, nor was information on the breakdown of funding among service components. Independent oversight or legislative scrutiny of acquisition planning, risk assessment, audits, or the procurement cycle remain lacking. Covering the period from 2021 to 2025, the law provides some details on the security sector’s planned operational and investment expenditures. It also details plans to recruit 6,800 troops and 3,000 gendarmes by 2025.

Togo has been a member of the Accra Initiative since its founding in 2017. The initiative includes Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. The security partnership aims to facilitate intelligence sharing, hold joint operations in border zones, and provide counter-terrorism training. In November 2022, members of the Accra Initiative announced the creation of a 10,000 strong multinational joint force to combat violent extremism, though its implementation remained uncertain.

In October 2021, Togo signed a military cooperation agreement with Turkey. The agreement aims to improve the military’s logistics and industrial capacities. In July 2022, Togo signed a military cooperation agreement with Benin which will facilitate information-sharing, aerial reconnaissance of militant movements and potential joint military operations.

Togo has a military academy, a peacekeeping training center, and a French-funded Army Medical Corps School. Many officers study abroad, particularly in France.

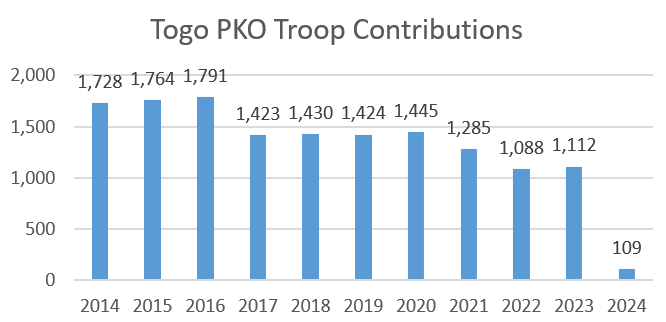

Capabilities

The armed forces’ materiel is comparable to West African counterparts, but their equipment is relatively obsolete. Until the December 2023 closure of the UN Mission in Mali, Togo was a significant contributor to UN peace operations, deploying almost 1,100 of its 19,000 strong Army to missions in Central African Republic, DRC, Mali, and South Sudan. It also participated in AFISMA, the AU’s 2013 mission in Mali. In 2022, the bataillon d’intervention rapide (BIR) was moved from a base in Sokode to Dapaong and equipped with Turkish Bayraktar TB2 armed UAVs.

The Air Force, with its ten fixed wing attack aircraft and four helicopters, makes Togo stand out from comparable security services. But maintenance for aircraft and ships remains a challenge. In 2016, the Navy was unable to project force 200 miles offshore to recover or monitor a hijacked ship because no military vessel had been adequately serviced.

Territorial Control

Togo’s 3,000 strong Customs Administration provides border control and security. Its agents are civil servants, but they also have military status. In August 2019, the customs services of Burkina Faso, Togo, and Niger agreed to establish an online tracking system for goods transiting through their countries.

Given its location on the Gulf of Guinea and Lomé’s role as a major West African port, Togo faces challenges related to trafficking. Togo is an important gold trading center because taxes on gold in the country are relatively negligible, consequently it has developed into a major gold smuggling hub. In Togo, many local criminal networks operate in drug trafficking, smuggling, contraband sales, and money laundering. These local networks serve as transporters for criminal and trafficking networks based in neighboring countries or overseas. It is presumed that these networks have strong ties with state authorities.

The government has stepped up its control of the northern regions where a state of emergency is in effect. Armed groups operate throughout the Togolese northern border zone where large national parks provide refuge for criminal and terrorist organizations. In November 2021, an attack a military base in the northern town of Sanloaga was repelled by security forces. Since this initial attack, more than 50 soldiers have been killed in militant attacks. From 2022 through the end of 2023, 32 incidents linked to violent extremists occurred resulting in at least 131 fatalities. Togo hosts around 28,000 Burkinabe refugees.

Until late 2023, when the number of incidents increased off the coast of Somalia, the Gulf of Guinea suffered the most incidents of piracy and maritime banditry in the world. Nonetheless, piracy continued to decrease in the Gulf of Guinea in 2023, with 31 incidents reported, down from 115 incidents in 2020. Sporadic acts of piracy and maritime banditry occur in Togo’s territorial waters. In a November 2020 incident, a Togolese-flagged tanker was attacked by armed pirates, an Italian warship assisted until a Nigerian Navy patrol boat arrived to escort the ship back to port. Two incidents were reported in 2020 and one in 2022. No incidents of piracy were reported in 2021 and 2023. Togo is a party to the Yaoundé Protocol, an effort by 25 West and Central African countries begun in 2013 to improve cooperation to curb illicit trafficking, and combat illicit fishing in the Gulf of Guinea. Togo sometimes conducts joint naval patrols with Benin.

Togo

Togo