Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Summary

Surging demand for ivory and rhino horn, mainly in Asia, has put wild African elephants and rhinoceroses on the path to extinction. More than an environmental tragedy, however, wildlife poaching and trafficking has exacerbated other security threats and led to the co-option of certain African security units. African states need to develop a broad range of law enforcement capabilities to tackle what is effectively a transnational organized crime challenge. Asian and other international partners, meanwhile, must take action to reduce runaway demand for wildlife products.

Highlights

- Spikes in the prices of ivory and rhino horn have propelled an escalation in killings of African elephants and rhinoceroses. Without urgent corrective measures, extinction of these populations is likely.

- This is not just a wildlife poaching problem but part of a global illicit trafficking network that is empowering violent groups and co-opting some elements of Africa’s security sector.

- An immediate bolstering of Africa’s wildlife ranger network is needed to slow the pace of elephant and rhino killings and buy time. Addressing this threat over the longer term will require dramatically reducing the demand for these animal parts, especially within Asian markets.

“I condemn poaching and condemn those who entice young people to go hunting, because the game they kill is not for them. … It is at the behest of the powerful. … There is someone who makes a lot of money (from hunting), but those who die are often young people who innocently do it thinking that it makes life easy, it makes easy money, but they lose their lives.”

Abooming black market trade worth hundreds of millions of dollars is fueling corruption in Africa’s ports, customs offices, and security forces as well as providing new revenues for insurgent groups and criminal networks across the continent. Rather than narcotics, small arms, or other commonly trafficked goods, however, it is record-breaking numbers of poached elephants and rhinoceroses that are driving this cycle of exploitation and instability.

Poaching is not a new problem in Africa. Its dramatic acceleration since the late 2000s, however, has significantly altered its implications. By some estimates, the number of African elephants killed annually since 2007 has more than doubled to over 30,000.1 The trend crossed a chilling threshold in 2010 as the rate of killings surpassed that at which elephants breed, indicating that significant net population declines have begun. Rhino poaching has also skyrocketed. Illegal killings in southern Africa from 2000 to 2007 were rare, frequently fewer than 10 a year. An explosion in poaching rates commenced in 2008. By 2013, 1,004 rhinos were poached in South Africa alone.

Soaring global prices for ivory and rhino horn are driving this poaching frenzy. In 2003, high-quality ivory sold for roughly $200 per kilogram. The same amount could fetch $2,500-$3,000 on the black market in 2013. The escalation in prices for rhino horn has been even more dramatic. Whereas a kilogram of rhino horn cost around $800 in the 1990s, it is now more valuable than gold. Some reports pegged the price of rhino horn in 2013 at $65,000 per kilogram. Thus, the horns from the 1,004 rhinos killed in South Africa may be worth $440 million. Such inflated prices, which exceed the value of cocaine and heroin in some countries, are overwhelming an already endangered species. The trend has even prompted a crime spree at some museums and auction houses with exhibits containing ivory or horn.

A carved ivory arm rest, Sichuan Provincial Museum, Chengdu, China. (Photo: Daderot.)

The proliferating number of middle- and upper-class consumers in Asia is the primary reason for the jump in prices. Typically valued as decoration, whether as carved jewelry or artwork or as mounted busts, ivory and horn have become a sought-after symbol of stature and wealth. In surveys of middle-class Chinese professionals, 87 percent associated ivory with “prestige” and 84 percent intended to purchase some.2

Another driver of the demand for rhino horn in Asia is the belief that it has powerful medicinal properties, including that it cures cancer. While such myths help explain the boom, consumers are surely overpaying. Rhino horn is just a fibrous protein called keratin, an inert substance that is similar in composition to human fingernails and hair.

Some of the consequences of wildlife trafficking are straightforward. It poses a severe threat to conservation and biodiversity in general. Poaching has led to the near extinction of some subspecies, including the disappearance of rhinos in Mozambique in 2012. Safaris and tourism are huge foreign currency earners for African countries, including over $1 billion annually for Kenya. These revenues will be severely affected as visitors encounter not only fewer animals but more criminality in game parks and reserves. Poaching also threatens these deeply rooted African icons.

Less understood is that the boom in wildlife trafficking poses substantial security threats. Various militia groups and criminal networks have been drawn to the illegal wildlife trade’s huge profits. Escapees from the Lord’s Resistance Army report that the group is trading ivory with Arab businessmen and officers from the Sudanese military for cash, food, guns, and medical supplies. Militants from Sudan have been blamed for incidents in which hundreds of elephants were killed in game parks in Cameroon. Seleka, the rebel militia that toppled the government in the Central African Republic in early 2013 and whose brutal treatment of the population triggered communal clashes across the country, reportedly poached elephants in the country’s reserves. The Somali Islamist militant group al Shabaab has also earned hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not more, from encouraging villages in Kenya to poach ivory, which is then trafficked out of Somali ports.3

The boom in wildlife trafficking poses substantial security threats.

Meanwhile, the trade in rhino horn has spawned new links between notorious Asian and Eastern European organized crime networks and those in Africa. The use of high-powered weaponry and advanced tactical gear by some poachers suggests how capable, well-funded, and dangerous these groups are. Scores of wildlife rangers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Kenya, and elsewhere are killed annually. During one incident in Chad in 2012 an entire squad of wildlife rangers were ambushed and killed by poachers.

The profits from wildlife trafficking have also fueled corruption, weakening and co-opting critical state institutions such as the police and military. In South Africa, evidence has linked former members of elite police and military units to rhino horn trafficking.4 In the DRC, scientists and park officials reported that Ugandan soldiers killed at least 22 elephants and retrieved more than $1 million worth of ivory during one cross-border sweep in March 2012.5 Other reports have implicated soldiers and units from the armed forces of the DRC, South Sudan, and Sudan. Wildlife trafficking’s high profits and low risk could fuel a sense of impunity within Africa’s security sector that further jeopardizes professionalism and triggers a range of other illegal and abusive activities.

While the depth of this new trafficking surge can only be estimated, it is no longer solely a conservation issue. With dozens of African countries affected by the growing demand for these products, wildlife trafficking has quickly grown into a serious regional threat.

The Poaching Challenge: The Case of Kruger National Park

(Photo: Anagoria.)

South Africa is home to more than 70 percent of the world’s rhinos, including 90 percent of Africa’s 20,000 white rhinos and 40 percent of the extremely rare black rhino. The majority of these animals reside in South Africa’s Kruger National Park (KNP). At some 2 million hectares, KNP is about the size of Israel. It shares a 356-kilometer border with Mozambique’s Lebombo Mountains.

Patrolling and monitoring this region is costly and difficult during even the best of times. Now, however, the park, and many like it across Africa, is being flooded by growing numbers of armed poachers. Many of these poachers have little training. Yet a substantial number work in sophisticated formations to evade detection and more effectively hunt their prey. Some are armed with automatic rifles and operate at night. Regardless of their sophistication, the sheer numbers are enough to overwhelm wildlife management agencies and ranger teams, even in comparatively well-resourced South Africa. In 2013, 86 poachers were arrested and 47 died during clashes with South African authorities just in KNP.

The support and complicity of some local communities, whether as poaching recruits or simply by ignoring illegal hunting activities, further complicates anti-poaching efforts. Surveys conducted in towns near Kruger found that 16 percent of respondents knew poachers living within their communities. Most respondents viewed poaching as a threat and 68 percent said they would be willing to identify offenders if they could be protected and poachers were jailed. However, fear of reprisals prompted many, even community leaders, to remain silent. Some respondents believed that police and rangers were directly involved in poaching.6 Similar dynamics are unfolding in Africa’s other poaching hotspots.

In 2012, South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs increased the number of deployed rangers in Kruger from 500 to 650. Command-and-control structures were streamlined and specialist units commissioned to analyze intelligence to increase response times against more mobile and sophisticated poachers. Expanded air services, canine capabilities, and several night operation enhancements have also helped. Collaboration with the South African Army, Air Force, and police has similarly been improved and institutionalized. Community programs have been launched to educate and foster local cooperation.

Significant challenges remain to reverse poaching trends, but these initial efforts are bearing fruit. While poaching numbers at Kruger have continued to rise, the pace is 22 percent lower than had been projected. There has also been a doubling in the annual number of poachers arrested.

Meanwhile, joint cross-border projects with Mozambican authorities are being devised, as are efforts to mitigate the appeal of rhino horns by coloring, removing, or otherwise altering them in ways that complicate smuggling (while doing no harm to the animals). Such initiatives represent a new anti-poaching approach meant to supplement classic ranger units with technology, local-level engagement, and collaboration at the interagency and international levels.

The Trafficking Challenge

Most poachers are not smugglers. Once ivory or rhino horn leaves Africa’s parks and reserves it is usually sold or transferred to criminal networks. These brokers and middlemen move the materials across borders and launder associated revenues. In many ways, these activities are very similar to drug, mineral, or arms trafficking. In fact, the high prices of ivory and rhino horn attract specialists from these transnational organized crime networks.

Earnings can vary, but a poacher might receive just $600 for an ivory tusk or a rhino horn. The trafficker, meanwhile, will reap a substantially higher proportion of the $3,000-per-kilogram price for ivory and $65,000-per-kilogram price for rhino horn in Asia, particularly if they are able to resell these goods close to the final retail transaction.

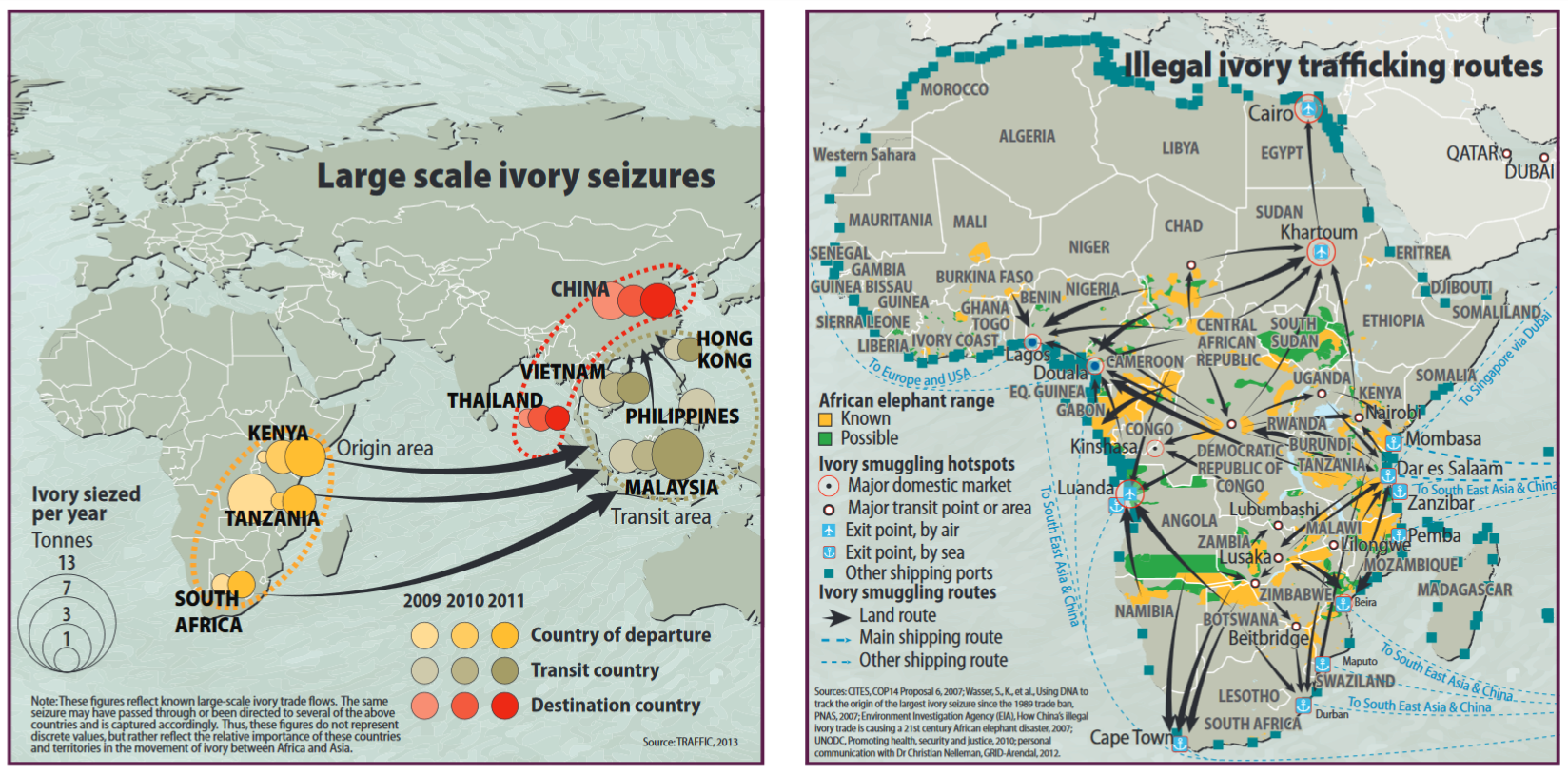

Traffickers must concoct a way to conceal ivory or horn shipments, usually within a consignment of legitimate goods through a front company to some export destination, often by shipping container and sometimes by air freight or commercial travel. Customs or other officials may be bribed to approve or certify transactions and paperwork. Based on seizure rates, Mombasa and Dar es Salaam appear to be primary points of departure from Africa, but traffickers use indirect routes or vary their points of exit and re-entry to avoid detection (see maps).

Source: Riccardo Pravettoni, GRID-Arendal.

Very few mid-level and high-level traffickers have been caught. The vast majority of arrests are of low-level poachers. One of the few central figures to have been convicted is a Thai trafficker named Chumlong Lemtongthai, who worked for businesses in Thailand and Laos and made frequent and long visits to South Africa. Lemtongthai was able to poach and traffic dozens of rhino horns out of South Africa. In fact, he was cleverly exploiting loopholes in hunting regulations to operate far more openly than many other poachers. Lemtongthai employed groups of Thai prostitutes, some working in Johannesburg and others flown in from Asia, to obtain licenses in South Africa that permit an individual to hunt one rhino a year. In reality, Lemtongthai’s network of hunters then killed dozens of rhinos using the permits. To ensure the hunts did not attract attention, Lemtongthai provided kickbacks to some parks and provincial officials as well as private reserve and game park owners in South Africa.7

Lemtongthai usually handled his numerous payouts by repeated cash withdrawals from casino ATM machines or by wire transfers from a Bangkok bank account. He then altered the official paperwork to redirect rhino horn shipments to his businesses in Southeast Asia rather than to the registered addresses of the supposed hunters (the prostitutes).8 In November 2012, Lemtongthai pled guilty to charges of violating South African customs regulations and illegally hunting protected species. Charges of money laundering were withdrawn, as were all charges against three South Africans and two Asians accused alongside Lemtongthai. Lemtongthai’s boss in Laos, Vixay Keovasang, has not been charged and allegedly continues trafficking wildlife, though in November 2013 the United States announced a $1 million reward for information on his activities. Reports indicate Keovasang benefits from extensive protection from Laotian government officials.9

Corruption is an issue elsewhere as well. The founding head of the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) has alleged that powerful individuals profiting from poaching have co-opted senior KWS officials. Officials from Tanzania’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism have been dismissed for involvement in wildlife trafficking. Even the secretary general of Tanzania’s ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi political party had to fend off accusations that he owned a stake in a shipping agent involved in ivory trafficking.10

In general, trafficking networks continue to operate with minimal fear of consequences. In many frontline countries such as Gabon and Mozambique, wildlife crimes are minor offences covered by relatively small fines. Some countries, such as Zimbabwe, have laws against poaching but not trafficking, essentially giving a free pass to the brokers and top-level criminals who facilitate the bulk of the trade.

The content of wildlife laws is only part of the problem. Enforcement of even relatively lenient penalties has been spotty across Africa. In a review of nearly 750 cases involving wildlife crimes in Kenya from 2008 through 2013, an independent Kenyan conservation group found that files were lost or misplaced in 70 percent of cases, due partly to poor management but also likely a sign of tampering and corruption. Among the 224 offenders for which there were records of conviction, just 8 went to jail while the vast majority paid small fines. In many cases, charges associated with organized crime, money laundering, or firearms offenses were applicable, though prosecutors rarely invoked them. Incidents of major seizures of wildlife goods in the port of Mombasa or in the town of Wajir near the Somali border were never pursued.11

Starting in 2014 new laws in Kenya instituted stiffer penalties for wildlife trafficking. Soon after, a Chinese national was convicted of smuggling 3.4 kilograms of ivory and ordered to pay a $233,000 fine or serve a sentence of 7 years in prison. Other countries, including Gabon, Mozambique, and Tanzania, are also drafting more severe penalties. However, effective deterrence will require not just harsher statutory punishments but also systematic application of the law.

Securing Africa’s Wildlife

Stemming the Upsurge in Demand

While the market for illegal wildlife goods is global, including in the United States and Europe, it is the growing numbers of middle- and upper-class consumers in Asia that have fed the exponential jump in prices for ivory and horn. So long as the trade remains so lucrative, some poachers and traffickers will inevitably attempt to exploit Africa’s wildlife treasures. Addressing the wildlife trafficking challenge, therefore, is ultimately about shrinking demand.

Many Asian consumers simply have a weak understanding of where ivory originates or its legality. In previous surveys, 70 percent of Chinese respondents were not aware that tusks mainly come from dead elephants.12 Consumer views of the rhino horn trade appear to be similarly under-informed.13 Few Chinese understand the role that criminal networks play in supplying these products.14 Asian demand for ivory, moreover, also seems to be highly influenced by government policies and pronouncements. About 60 percent of surveyed Chinese consumers said that recommendations from government leaders to avoid ivory or outright bans would sufficiently persuade them to avoid ivory purchases. Nearly 40 percent indicated that their consumption was affected by a sense of remorse when they learned that elephants are killed to source ivory.

To fundamentally reshape the demand for illicit ivory and rhino horn, a high-profile public education and awareness-raising campaign in Asia is needed. Experience suggests significant impacts can be realized. High demand for shark fin soup across Asia has been dramatically lowered through effective social marketing. With the right combination of high-profile campaigners, resonant messaging, and consistent engagement, the same success might be achieved in the ivory and rhino horn markets.

More attention also needs to be paid to Asian governments that have been slow to address the problem. In China, for example, government officials have openly called for an expansion of the licit market for ivory.15 Such a position ignores the need to rein in demand and the incentives that are driving destabilizing poaching and organized crime activities in Africa. Asian governments should support a ban on ivory sales and more actively discourage their citizens from buying ivory and rhino products. This would also be a service to the many Asian buyers who are wasting thousands or tens of thousands of dollars on these wildlife products for their bunk medicinal properties.

Strengthening the Frontlines

While curbing the wildlife trafficking trade is dependent on reshaping demand, investing in frontline actors is critical for slowing the devastation of Africa’s rhino and elephant populations—buying valuable time. Most African states already benefit from dedicated and experienced wildlife ranger corps. However, the exponential increase in poachers, particularly sophisticated and well-armed ones, calls for reforms and better resources. As in Kruger National Park in South Africa, the command-and-control structure of these ranger corps will need to be revised to allow for rapid relay of information to a central command post that can quickly reposition and redirect units as needed.

New equipment will also be vital to enhance the mobility and domain awareness of rangers. Small planes, helicopters, and unmanned aerial vehicles have achieved positive results at reserves in Chad, Kenya, and South Africa. Information technology can provide further advantages. One reserve in Kenya installed triggers on fences and embedded trackers in elephants to alert rangers’ mobile phones by text message when security perimeters were tampered with or when animals were behaving abnormally. Technology will also be crucial to the extensive recordkeeping necessary to analyze ranger deployments, poaching patterns, and biometric and forensic data on wildlife remains.

However, technology should not eclipse the need for well-trained and well-resourced rangers. No number of helicopters or advanced gadgetry can top the effectiveness of a ranger who knows the bush, can spot the easily overlooked signs of intruders, can operate for days or weeks without resupply, and is willing to put himself or herself in harm’s way. New highly trained units in South Africa and Mozambique provide models that could be replicated elsewhere on the continent.

Community Engagement

African communities located near Africa’s parks and reserves live in the thick of the escalating poaching crisis and will be key to its reduction. Through effective engagement and support, these communities can work to dissuade youth from poaching and provide crucial intelligence on illicit activities.

Trafficking networks continue to operate with minimal fear of consequences.

Similar community engagement initiatives should be a top priority for other African wildlife management agencies. At the very least, governments should avoid the inevitable anger and resistance from local communities generated by aggressive “shoot-to-kill” army deployments, which often lack the technical expertise demanded in anti-poaching efforts. In Tanzania, anti-poaching and army units were given wide latitude during emergency deployments in 2013. Soon after, killings, rapes, and severe abuses were reported and the initiative was ended early.18

Strengthening Investigations and Prosecutions

Africa’s wildlife crisis is not just a poaching challenge but involves sophisticated criminal networks employing advanced trafficking techniques. Stemming this organized crime component of the illegal wildlife trade will require law enforcement and prosecutorial measures adept at combating illicit networks.

Stronger institutional exchanges with wildlife management agencies should be established so that police and customs officers are familiarized with wildlife products and are on the lookout for tell-tale signs of suspect shipments. The careful collection of forensic evidence from seizures at seaports and airports is also critical to linking illegal shipments to broader criminal networks and achieving eventual prosecutions.19 In late 2010 the International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime (ICCWC) was established to facilitate such linkages and training in advanced techniques. For instance, the ICCWC conducted field training for officers from several African and Asian countries on the population and use of a database of rhino DNA. This database and similar ones for elephant DNA are critical to mapping trafficking patterns and the dismantlement of transnational networks.

Criminal investigative units should be targeting wildlife trafficking networks to identify the senior leaders who often orchestrate the most extensive illegal activity but tend to be removed from on-the-ground poaching and smuggling. This will require closer examination of the businesses and financial transactions that facilitate wildlife trafficking. As such, cooperation with revenue authorities, corporate registries, and property registries will need to be improved, and databases with this information should be modernized and made more easily accessible. Financial intelligence units will be critical to “following the money” that is laundered for wildlife transactions. Fortunately, the detailed “Wildlife and Forest Crime Analytic Toolkit” developed jointly by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and several top wildlife nongovernmental groups lays out the investigative techniques and interministerial cooperation needed to combat wildlife trafficking. Establishing interagency taskforces, moreover, would reinforce the priority of mounting determined countermeasures that encompass multiple ministerial authorities.

Fines for wildlife crimes should at the very least exceed the value of the wildlife products seized from offenders.

Strengthening penalties for wildlife offenses are also vital to combating the illicit trade. Fines for wildlife crimes should at the very least exceed the value of the wildlife products seized from offenders. Likewise, bail should not be an option for individuals involved in large seizures, since they are likely to have the means to pay and the incentive to disappear. Given the economic and security implications of the growing illegal wildlife trade, offenders should face significant prison sentences and judges should avoid thinking of wildlife crimes as petty offenses.

The implementation of new penalties will also require more training and resources for judges, prosecutors, police, and wildlife authorities. With escalating prices for ivory and rhino horn, courts are likely to see a high volume of wildlife-related cases. As in some drug or corruption cases, special procedures and fast-track courts may be needed to ensure speedy trials that do not end in dismissals due to delays or technicalities. Police and prosecutors should also think more broadly about the crimes involved in poaching and wildlife trafficking and apply laws against economic crimes, organized crime, firearms offenses, and other relevant charges. The strategic use of plea bargains and leniency against low-level offenders could also be used to build cases against higher-level financiers and brokers.

Unfortunately, the growing levels of corruption associated with the lucrative wildlife trade are seriously compromising efforts to fight it. State institutions charged with combating armed groups and organized crime, including elements of militaries, police, customs bureaus, and even some politicians, have been implicated in wildlife trafficking. African statesmen and political leaders need to bring attention to this co-optation and institute appropriate oversight measures to prevent it. Internal affairs offices in African security services should be instructed to investigate wildlife trafficking. Whistleblowing opportunities and protections should be enhanced. A new secure online initiative that links whistleblowers with investigative journalists called WildLeaks (www.wildleaks.org/) launched in February 2014 may demonstrate how technology can create more opportunities to safely shine a light on the corruption that facilitates wildlife trafficking. The wildlife trade also needs to be on the agenda of anti-corruption commissions, where asset and financial disclosures of state officials should be reviewed for connections to potential trafficking activities.

Growing levels of corruption associated with the lucrative wildlife trade are seriously compromising efforts to fight it.

Due to its expanding influence and consistent effectiveness, the government of Cameroon includes LAGA as part of its delegation to meetings of the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Other governments and wildlife NGOs in Africa could similarly collaborate to expand the resources available to combat trafficking and limit the use of corruption as a means to facilitate wildlife crime.

Stronger Regional and International Cooperation

African governments will also need to work collaboratively to pool resources, share information, and align diplomatic efforts. Several nations have already begun working together to shore up ranger deficiencies. Gabon has deployed its comparatively advanced wildlife ranger units to the Central African Republic to address cross-border poaching. Mozambique and South Africa are likewise collaborating to develop new advanced units and strengthen cross-border cooperation. Institutionalized cooperation and information-sharing among African and Asian law enforcement and customs bureaus are equally important.

African governments can also work together to avoid past missteps that helped fuel the recent surge in demand for ivory and rhino horn. Through CITES, which governs legal wildlife transactions, four African governments were permitted a one-time sale of 102 tons of ivory that had been stockpiled from elephants that died naturally. The four auctions to traders from China and Japan in 2008 for $15 million has frequently been described as the trigger for a subsequent surge in demand that notched up prices, which, in turn, drew various organized crime groups and militants to poaching and trafficking.20

In the run up to the next CITES conference in 2016, South Africa is exploring a proposal for a one-time sale of 18 tons of stockpiled rhino horn, the proceeds from which it promises to earmark for conservation. Any benefits from the sale will likely be overshadowed by a spike in demand that will drive even more poachers and criminals into South Africa’s game parks. Recognizing such a risk, four African states (Botswana, Chad, Gabon, and Tanzania) vowed in February 2014 to forgo any future sales of stockpiled ivory. Notably, Botswana was involved in the fateful 2008 ivory sale.

Conclusion

Based on current trends, Africa faces a not too distant future absent some of its most unique and recognizable natural heritage—elephants and rhinoceroses. This outcome is the direct result of rising global demand for “prestige products” and the predatory behavior of organized crime groups seeking lucrative profits. Wildlife trafficking is no longer just a conservation problem but has metastasized to a security problem. Together with international governmental and nongovernmental partners, African states need to act more urgently to implement a strategy to slow and eventually reverse this fast-moving threat—and protect their natural resources for future generations.

Notes

- ⇑ UNEP, CITES, IUCN, and TRAFFIC, Elephants in the Dust: The African Elephant Crisis (Norway: GRID-Arendal, 2013), 32-33. “Tracking Poached Ivory,” Center for Conservation Biology at the University of Washington.

- ⇑ John Bredar, “The Ivory Trade: Thinking Like a Businessman to Stop the Business,” National Geographic, February 26, 2013.

- ⇑ Marina Ratchford, Beth Allgood, and Paul Todd, Criminal Nature: The Global Security Implications of the Illegal Wildlife Trade (Washington, DC: International Fund for Animal Welfare, 2013), 12-14.

- ⇑ Darren Taylor, “New Breed of Poacher Decimates African Rhino,” Voice of America, January 20, 2012.

- ⇑ Ratchford et al., 14.

- ⇑ Mandi Smallhorne, “Think Local to Save Rhino,” Mail & Guardian, November 1, 2013.

- ⇑ Fiona Macleod, “Poachers, Prostitutes and Profit,” Mail & Guardian, July 22, 2011.

- ⇑ Julian Rademeyer, Killing for Profit: Exposing the Illegal Rhino Horn Trade (Cape Town: Random House Struik, 2012).

- ⇑ Julian Rademeyer, “Rhino Butchers Caught on Film at North West Game Farm,” Mail & Guardian, November 9, 2012.

- ⇑ “Kinana Refutes Ivory Trafficking Claims Made by Opposition MPs,” The Guardian, May 8, 2013.

- ⇑ Paula Kahumbu, Levi Byamukama, Jackson Mbuthia, and Ofir Drori, Scoping Study on the Prosecution of Wildlife Related Crimes in Kenyan Courts, January 2008 to June 2013 (Nairobi: Wildlife Direct, 2014).

- ⇑ Per Liljas, “The Ivory Trade Is Out of Control, and China Needs to Do More to Stop It,” Time, November 1, 2013.

- ⇑ “Rhino Horn Demand,” WildAid, 2012.

- ⇑ Impact Evaluation on Ivory Trade in China, IFAW PSA: ‘Mom, I Have Teeth’, Rapid Asia Flash Report (China: International Federation for Animal Welfare, May 2013).

- ⇑ Dan Levin, “From Elephants’ Mouths, an Illicit Trail to China,” The New York Times, March 1, 2013.

- ⇑ Brigitte Weidlich, “Namibia Offers Model to Tackle Poaching,” South African Press Agency/Agence-France Presse, January 26, 2013.

- ⇑ Garth Owen-Smith, A Brief History of the Conservation and Origin of the Concession Areas in the Former Damaraland (Windhoek: Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation, November 2002). Daisy Carrington, “How Namibia Turned Poachers into Gamekeepers and Saved Rare Wildlife,” CNN, October 23, 2012.

- ⇑ Kizito Makoye, “Anti-Poaching Operation Spreads Terror in Tanzania,” Inter Press Service, January 6, 2014.

- ⇑ Interview with Justin Gosling, independent wildlife crime consultant, February 21, 2014.

- ⇑ Bryan Christy, “China Ivory Prosecution: A Success Exposes Fundamental Failure,” National Geographic, May 30, 2013.

Bradley Anderson is the Regional Manager in the East Africa office of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. Johan Jooste is the Commanding Officer for Special Projects in the South African National Parks service and retired as a Major General from the South African National Defence Force.