Download PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Peace operations have been a principal tool used to curb conflict in Africa over the past decade, with over 40 operations deployed since 2000. This Security Brief takes stock of lessons learned from these experiences and the implications they hold for improving the effectiveness of future peace operations in Africa.

A Ghanaian peacekeeper with the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) is pictured on guard duty during a visit by Karin Landgren, Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Head of UNMIL, in Cestos City, Liberia. Photo: UN Photo/Staton .

Highlights

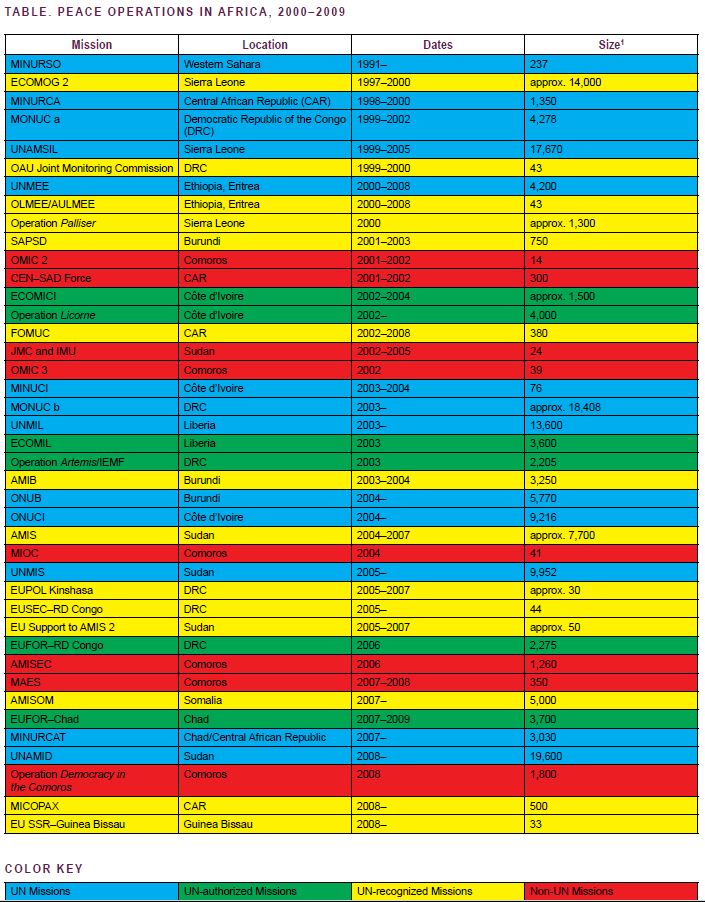

- There have been 40 peace operations deployed to 14 African states since 2000.

- To be successful, peace operations must be part of an effective political strategy and peace process, not a substitute for them.

- Policymakers need to move beyond a preoccupation with the number of personnel deployed for each mission and focus on what capabilities are needed to generate the desired political effects.

- Maintaining legitimacy is a crucial part of achieving success.

Reducing the incidence of armed conflict remains a defining priority for Africa. The continent’s recent conflicts have killed millions and displaced many more, leaving them to run the gauntlet of violence, disease, and malnutrition. These conflicts have also traumatized a generation of children and young adults, broken bonds of trust and authority structures among and across local communities, shattered education and health care systems, disrupted transportation routes and infrastructure, and done untold damage to the continent’s ecology from its land and waterways to its flora and fauna. In financial terms, the direct and indirect cost of these conflicts is well over $700 billion.1

Peace operations are arguably the principal international instrument to curb conflict in Africa. Since 2000, the United Nations (UN) alone has spent over $32 billion on its 12 peacekeeping operations on the continent, of which the U.S. Government contributed roughly one-quarter. For some, this has been a good investment. The Human Security Brief 2007, for instance, concluded that the rise in peace operations since the mid-1990s was a major contributing factor to the 60 percent decline in the number and magnitude of African conflicts over the same period.

The current resurgence of peace operations began in 1999 with the UN missions in Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) following a U.S.-led withdrawal from peacekeeping in Africa after the so-called Black Hawk Down episode in Mogadishu in October 1993. Since then, 40 missions (see table) have been deployed to 14 African states, many of them into tough environments with a long list of difficult tasks to achieve. They were conducted by a range of international organizations, principally the UN, African Union (AU), and European Union (EU). A small number were also undertaken by individual states, principally France, South Africa, and the United Kingdom.

This resurgence indicates that governments (both within and beyond Africa) saw peace operations as a viable and effective tool of conflict management. In some respects, this perception was justified. Among other things, peace operations have assisted several states during the transition from war to peace; helped mitigate humanitarian crises and protect civilians; changed the incentives for war and peace among the belligerents, sometimes by actively coercing “spoilers”; assisted in the reduction of uncertainty between various conflict parties; helped prevent accidents and control skirmishes, which otherwise might have escalated to war; and facilitated political dialogue between belligerent groups.

But these operations have also generated controversy. On the ground, peacekeepers have not always extinguished the flames of war or managed to protect its civilian victims. Moreover, too many (military and civilian) personnel from various organizations have been accused of incompetence, corruption, and sexual exploitation of the people they were supposed to protect. At the UN, some of these missions have generated tensions because Western states, in particular, have pushed to establish increasingly ambitious operations with larger numbers of personnel, but have been reluctant to deploy their own soldiers or provide sufficient materiel. This has produced a significant mismatch between the states making the key strategic decisions and the states risking their personnel on the ground. In financial terms, the cost of these operations has risen at a time when the recent global economic downturn has constricted resources.

This brief reviews the major strategic and operational lessons learned from the 40 peace operations that were deployed to Africa since 2000 with the aim of making these and future operations more effective instruments of conflict resolution.

Key Lessons

There are many mission-specific lessons to draw but six general lessons bear highlighting.

An Effective Political Strategy Is a Prerequisite for Success. Peacekeeping is an instrument, not a strategy. To be successful, peace operations must be part of an effective political strategy and peace process, not a substitute for them. Without a viable political strategy, peace operations should not be an automatic response to all wars. As U.S. Ambassador to the UN Susan Rice recently put it, “peacekeepers cannot do everything and go everywhere.” First and foremost, they should not be deployed to active war zones unless they are part of a viable political process for managing or resolving the conflict. Nor should peacekeepers be deployed unless they have active cooperation from the host government(s) in question. They should generally avoid crossing what has been dubbed the “Darfur line”—“deploying where there is no (real) consent by the state.”2 If civilians are being systematically massacred by their own governments and international society wants to stop it, then a peace enforcement intervention rather than a peacekeeping operation is needed.

Strategic Coordination Is Crucial. Peace operations usually involve a variety of actors (states, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations [NGOs]) working in the same environment. Strategic coordination among them is therefore crucial. It will be more likely to occur if policymakers recognize at least three things. First, since different organizations will always maintain their own distinct agendas, coordination needs to be treated as a political, not just technical, exercise. Second, since the early 1990s, the UN has clearly been the single most important organization for conducting peacekeeping in Africa. Other institutions have also played important roles—particularly the AU, which has deployed over 15,000 peacekeepers, and the EU, which has conducted seven peace operations on the continent. Consequently, strategic coordination in Africa should focus on developing sensible divisions of labor within the complicated UN–AU–EU nexus; clarifying how the continent’s subregional arrangements, including the regional brigades of the African Standby Force, are supposed to relate to the AU; and ensuring that policymakers do not overestimate the AU’s current capabilities.3 Third, policymakers need to work hard to ensure that the relevant actors—especially states contributing personnel and members of the authorizing institution—share a similar vision of the operation’s purpose, mandate, and rules of engagement (ROEs).

Ends and Means Must Be in Synch. To be successful, peacekeepers must be given the resources necessary to achieve their goals. There are at least two dimensions to this issue. First, the goals of an operation should be neither contradictory nor technically impracticable. They should be set out in clear, credible, and flexible mandates with appropriate ROEs. For ex- ample, policymakers should avoid the strategic headache handed to the UN Mission in the DRC (MO- NUC), which was told to assist successive Congolese governments that were as much a part of the country’s problems as the rebels. Second, once mandated, policymakers need to prevent large discrepancies from developing between the authorized force levels and the actual numbers of personnel on the ground. Such personnel gaps not only hamper a mission’s ability to take advantage of the so-called golden hour immediately after the cessation of fighting, but they also signal to the conflict parties a lack of political will within the authorizing organization. The good news is that with the exception of the AU/UN Hybrid Operation in Darfur’s (UNAMID’s) first year in Sudan, the UN has made substantial progress in reducing its vacancy rates. The AU, however, has failed to quickly deploy the authorized number of troops in its missions in Burundi, Sudan, and Somalia. In Somalia, it is still struggling to enlist and deploy the 8,000 peacekeepers that it authorized for the operation in January 2007. Reducing vacancy rates at the AU will require building a broader pool of significant troop and police contributing countries, and finding more strategic lift capabilities to ferry personnel into the theater of operations.

“peacekeepers should not be deployed to active war zones unless they are part of a viable political process for managing or resolving the conflict”

Define and Deliver “Robust” Operations. In 2000, the so-called Brahimi Report concluded that once deployed, peace operations must be based on robust doctrine, force posture, and ROEs that do not “cede the initiative to their attackers.”4 This would enable missions to achieve their mandated tasks as well as protect their own personnel and local civilians. Ideally, military units within peace operations should be strong enough to deter parties from using force against peacekeepers and civilians. This is important because weak missions have frequently fallen prey to spoilers. The decade began with hundreds of UN peacekeepers taken hostage by rebels in Sierra Leone. At least by the decade’s end (in late 2009), two UNAMID peacekeepers held hostage in Darfur for more than 100 days were released relatively unscathed. While it is hard to argue against the idea of “robustness” in principle, what it should mean in practice needs greater clarification. Operations that envisage threatening or using force to protect the mandate, civilians, and their own personnel clearly need to be authorized under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. But this alone does not clarify what types of military capabilities or ROEs are most suitable for a particular operation.

Focus on Effects, Not Just Numbers. Issues related to force generation—that is, getting enough peacekeepers on the ground quickly—have always been a crucial component of peace operations. But in order to be successful, peace operations must generate particular political effects in the theater such as coercing spoilers, protecting displacement camps and supply routes, or promoting the rule of law. As a consequence, policymakers need to move beyond a narrow preoccupation with deploying a particular number of personnel for each mission and focus instead on what capabilities are necessary to generate the desired political effects. The more complex the tasks given to peacekeepers, the more niche capabilities they will require. Among the most important for multidimensional operations are engineer and medical units, communications and logistics capabilities, field intelligence, formed police units,5 and special forces. To this list should be added the general need for more female peacekeepers, not least because of the significant roles they can play in relation to information-gathering, policing, and responding to the challenges of sexual and gender-based violence. Appropriate vehicles are also crucial, particularly armored personnel carriers, helicopters, and unmanned aerial vehicles. These will need to come from outside the continent since African states currently provide very few of the UN’s 26 engineering units or its 177 helicopters.

“peacekeepers are never in total control of their legitimacy because it depends on the perceptions of other actors”

Legitimacy Matters. In peace operations, maintaining legitimacy in the eyes of the relevant audiences—including the conflict parties, local civilians, international NGOs, and foreign governments—is a crucial part of achieving success. Importantly, peacekeepers are never in total control of their legitimacy because it depends on the perceptions of other actors. The situation is made more complex because the relevant audiences may well come to different conclusions about the legitimacy of the same actor or action. Operations perceived as legitimate will be more likely to achieve their objectives, not least because they will find it easier to attract personnel, funds, and political support, and locals will provide them with good intelligence and other forms of assistance. Operations perceived as illegitimate will struggle on both counts, as the AU mission in Somalia has found to its considerable cost. Irrespective of the specific details of the mandate, a peace operation’s legitimacy can be eroded by various forms of behavior, most notably when peacekeepers are accused of committing war crimes—for example, African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), failing to protect civilians from violence (UNAMSIL, AMIS, MONUC), corruption (MONUC, AMISOM), and sexual exploitation and abuse (MONUC, UNMIL). The potential for illegitimate behavior will be reduced by ensuring that peacekeepers are well trained to cope with the challenges they are likely to face in the field, follow similar codes of professional ethics, are adequately paid during their tours of duty, and are punished if found guilty of illegal acts.

Policy Implications

In light of these lessons, a number of practical steps can be taken to address the challenges raised by contemporary peace operations in Africa.

Clarify Mission Tasks. First, there needs to be greater clarification about the tasks that peacekeepers should be able to deliver (and those that are beyond them). Once agreed, these should be translated into clear doctrine, guiding principles, mandates, and ROEs. The UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, in particular, has made important advances in these areas in recent years, most notably through the publication of its Principles and Guidelines. But some priority topics still require more attention, including disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration schemes; security sector reform initiatives; civilian protection; rule of law functions; and the military’s role in the provision of humanitarian relief. The central fault line in international debates continues to be over whether peace operations should fulfill many wider peace-building tasks beyond those necessary to provide military stability in the theater. Without a greater degree of consensus on these fundamental issues, it will be impossible to design effective mandates and curricula for “training” peacekeepers or to know what resources missions will need.

Prioritize Peace Operations to Support Effective Peace Processes. Policymakers should put more resources into designing effective peace processes that address the causes as well as the symptoms of armed conflicts. Indeed, the merits of deploying a particular peace operation should be assessed with direct reference to the prospects for constructing a successful peace process. Stalled peace processes in Sudan and Somalia as well as the DRC and Côte d’Ivoire emphasize the importance of this point. Constructing effective peace processes is never solely about providing more money, although funds spent wisely will usually help. Rather, it requires the provision of better and sustained mediation from senior political figures as well as greater organizational support for them. Moreover, mediators and their teams who are permanently based in the region concerned will be more likely to have a positive impact than special envoys who make only fleeting visits to the conflict zone in question. Effective mediation requires an ability to engage in sustained dialogue with lots of local groups, not only the leaders of armed factions. Although Darfur is probably the best example of a conflict that attracted an extraordinary amount of international attention that failed to be translated into an effective peace process, the AU High-Level Panel on Darfur provides a useful model for stimulating a reconciliation process and is worthy of replication elsewhere.

Design Better Entry and Exit Strategies. Knowing when and where to deploy peace operations and when they should leave is a fundamental but underdebated question. With regard to getting in, more thought needs to be given to the issue of consent: whose consent is essential, whose consent is desirable but not essential, and what should be done if these actors withdraw their consent or place additional conditions upon it after peacekeepers deploy? In particular, policymakers need to decide how they should protect civilians when a sitting government is perpetrating atrocities against elements of its own population. The greater the level of international consensus on these fundamental issues, the better. A lack of consensus will complicate matters when deciding on an exit strategy. Indeed, questions about appropriate exit strategies and the benchmarks to assess a mission’s ongoing performance need more systematic analysis. This is particularly important for operations with state-building components to their mandates and those helping to strengthen state authority in the face of armed challengers (for example, AMISOM and MONUC). Combined with the issue of consent, such benchmarks would help clarify how to proceed when debates emerge over how and when to end operations (as is currently occurring with regard to UN- MIL, MINURCAT, and MONUC). At a minimum, senior peacekeeping officials (military and civilian) fresh from the field should be brought together with analysts regularly to reflect upon these issues and record their conclusions.

“knowing when and where to deploy peace operations and when they should leave is a fundamental but underdebated question”

Deliver More and Better Resources. Failed peace operations seriously damage the credibility of the organization(s) involved, do a great disservice to local civilians, and sometimes even endanger the notion of peacekeeping itself. As a consequence, once the decision has been made to deploy an operation, maximum international effort should be expended to ensure that it succeeds. In time, a critical mass of successful missions will invigorate the peacekeeping brand and strengthen the credibility of the UN Security Council and other peacekeeping actors such as the AU and EU. Peacekeepers therefore deserve to be given more and better resources. Specifically, resources are needed to overcome personnel overstretch, assets/capabilities overstretch, financial overstretch, and headquarters/command and control overstretch. Shortfalls in personnel and capabilities of the kinds discussed above should be relatively easy to overcome if the world’s most advanced military powers made a more serious commitment to UN peace operations. At the AU, more of the organization’s 53 members need to be persuaded to train and then deploy their troops and police on peace operations. In financial terms, the costs have grown steadily as peace operations have been asked to carry out more and more tasks, often in inhospitable environments. The good news is that compared to operations conducted by the world’s most advanced military states in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, UN peacekeeping is cost effective. At around $8 billion in 2008–2009, the UN peacekeeping budget is less than 1 percent of global military spending. In relation to command and control structures, more well-educated management personnel are needed within the relevant secretariats of the crucial organizations, particularly the UN and AU.

Recruit More Civilians. An important part of tackling these overstretch issues will hinge on strengthening the civilian elements of peace operations, especially police and civilians with expertise in rule of law issues, engineering, agriculture, and other development issues. Although civilians can actually be more expensive to deploy per head than troops, when an operation’s strategic objective involves building a self-sustaining peace and not only carrying out specific military tasks, they are an essential component of the mission and should be prioritized accordingly. Policymakers therefore need to think hard about where to find significant numbers of well-qualified civilians and how to persuade them to commit significant periods of time to working with peace operations. Importantly, this should include hiring more local civilians as well as foreigners. At the same time, creating a bigger pool of highly qualified senior mission staff will also go a long way toward addressing the command and control challenges identified above.

Conclusion

Peace operations in Africa have revealed some of the best and worst dimensions of peacekeeping. Despite a range of valid criticisms and serious imperfections, peace operations remain international society’s principal tool of conflict management, and empirical evidence suggests they have contributed to the decline of conflict in numerous war-torn territories. To use a clichéd phrase, if peace operations did not exist, it would be wise to invent them. Like any good creation, however, reform is needed to reflect those elements that are working well and change those that have failed. Accordingly, policymakers and analysts alike should work to ensure peace operations are given sensible operational directives, clear mandates, and sufficient resources to fulfill the proposed objectives. The resulting success stories would contribute to the downward trend in the number and magnitude of African conflicts, reduce the human and economic cost of violence, and thereby open the door to more dynamic and sustained development.

Notes

- ⇑ Based on Paul Collier’s estimate that the cost of each “typical” civil war in a low-income country is approximately $64 billion. See <http://users.ox.ac.uk/~econpco/research/conflict.htm>. A conservative estimate could identify 11 such wars in Africa since 2000 (Angola, Burundi, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Nigeria, Somalia, Sudan [twice], and Uganda).

- ⇑ Bruce Jones et al., Building on Brahimi: Peacekeeping in an Era of Strategic Uncertainty (New York: Center on International Cooperation, April 2009), 12.

- ⇑ See Paul D. Williams, “The African Union’s Peace Operations: A Comparative Analysis,” African Security 2, nos. 2/3 (2009), 97–118.

- ⇑ Report of the Panel on UN Peace Operations, UN document A/55/305–S/2000/809 (New York: UN, 2000).

- ⇑ These are specialized, armored police units consisting of approximately 125 officers from a single country.

Paul D. Williams is Associate Professor in the Elliott School of International Affairs at The George Washington University. Among his publications is Understanding Peacekeeping, 2d ed. (Polity Press, 2010).