Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Community-based security groups are emerging in African cities in response to rising crime and overstretched police forces. Experience from Abidjan shows that collaboration with the police, avoiding coercive tactics, and retaining citizen oversight councils are key to the effectiveness of these groups.

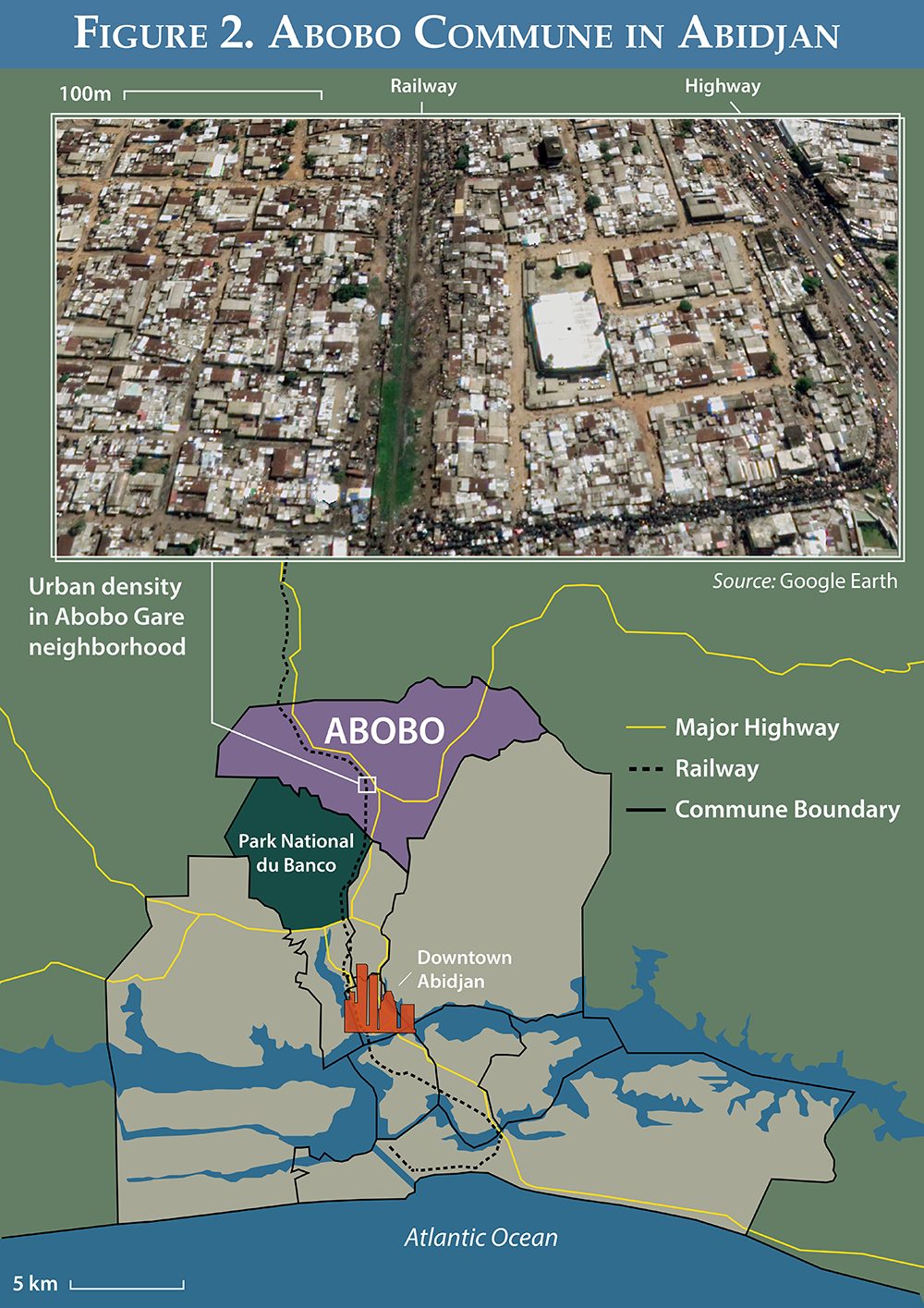

The Abobo commune in Abidjan. (Image: Google Earth)

Highlights

- Africa’s rapidly expanding cities are witnessing unprecedented levels of violent crime and the growing menace of criminal gangs. Exceeding the capacity of police, these dangers pose threats to citizen security, livelihoods, and the governability of urban areas.

- In response to these security crises, community-based security groups are emerging as a form of collaborative policing. While not a substitute for police, these groups can help address rising urban crime. Since they know their neighborhoods, these groups can act as go-betweens for overstretched local police and citizens.

- The most effective vigilance committees recognize that coercive tactics and violent confrontations with youth gangs escalate hostilities and fail to address deeper community problems. This will require tackling systemic factors linked to high crime rates in order to redirect youth gangs and stem urban violence.

- Experience from Abidjan reveals the limits of these vigilance committees in tackling serious crimes as well as the risk that these committees can turn to extrajudicial violence and become a threat themselves. This highlights the importance of close partnerships between vigilance committees and the police if collaborative policing models are to contribute to community security.

- Civil society engagement and community oversight are needed to regulate community-based security groups and ensure that they are not misused by local elites or corrupt police.

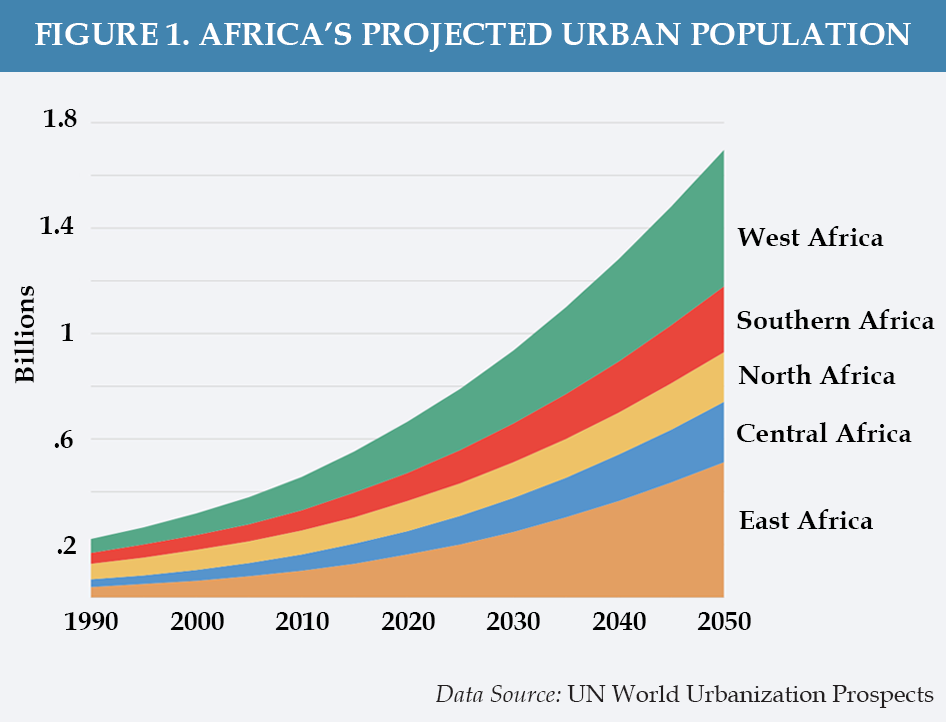

Africa’s urban population grew from 27 million in 1950 to 567 million in 2015. As Africa’s population is expected to double by 2050, estimates project that more than an additional billion people will live in African cities within the next 30 years (see Figure 1). These rapidly expanding urban landscapes have produced escalating security challenges for residents including petty theft, burglaries, car jackings, armed robbery, extortion, and kidnapping. Forty percent of Africans living in urban areas have reported feeling unsafe walking in their own neighborhoods.1 After the Americas, the African continent has the highest homicide rates in the world.2 These trends have contributed to the image of “the trembling city.”3

Security in Africa’s urban settings is in a state of constant flux reflecting the rapidly changing and often unplanned nature of urban areas, resource limitations, inadequate training, and politicized police structures.4 This has produced police forces often beholden to powerful local interests. These forces are prone to discriminate against marginalized and vulnerable groups, applying harsh practices inherited from colonial rule in which citizens were perceived as a threat. The uneven distribution of police officers and their resources, furthermore, has often led to the prioritization of wealthy and ruling party interests over communities. This has contributed to reduced trust between the police and the public.

In response to high levels of insecurity and limited police presence in African cities, forms of community or collaborative policing have emerged to protect ordinary citizens. In Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, such community-based security groups have taken the form of “vigilance committees.” Often initiated with a high degree of local legitimacy, vigilance committees are fundamentally relational, connecting community members to police forces, local authorities, and alleged delinquents and criminals.

Without monitoring, however, such groups can become a law unto themselves contributing to insecurity through extortion, human rights abuses, and vigilante justice.5 They can also be coopted by political actors and used as a tool for repression and violence, especially by authoritarian-leaning parties and politicians.6

The Case of Abobo

Abidjan is the third largest Francophone metropolis in the world after Paris and Kinshasa, with more than 5 million inhabitants. It is one of Africa’s fastest growing cities characterized by booming, but non-inclusive, economic growth. This has produced stark inequalities for residents, particularly youth.

The municipality or commune of Abobo is one of thirteen in Abidjan (see Figure 2). Comprised predominantly of working-class residents and more than 1 million inhabitants, Abobo ranks as one of the metropolis’ densest sectors. This borough concentrates old and recent arrivals mostly from the Sahelian region, including Malinké and Sénoufo Ivoirian groups from northern Côte d’Ivoire alongside Burkinabè and Malian émigrés. The commune developed around the colonial railway and, subsequently, the social world of urban transport including taxis and the iconic Gbaka minibuses. This essential sector ferries blue-collar workers between dormitory boroughs like Abobo and places of industrial or commercial activity. Its role as a transportation hub has also integrated Abobo into Abidjan’s networks of organized crime.

Police repression and harassment of Abobo’s population have a long history. Police have targeted residents, especially young people working in transportation, applying the xenophobic discourse of “Ivoirité,” which denied northerners’ basic rights claiming they were nonindigenous. This has fostered a culture of suspicion and mistrust between the police and Abobo residents. The borough was also Abijdan’s bedrock of revolt against Laurent Gbagbo’s effort to stay in power after his electoral defeat in 2010-2011, which further soured relations between the police and local populations.

Following the 2010-2011 crisis, gangs erupted around Abidjan fueled by the latest generation of marginalized youth and nicknamed with the stigmatizing expression “microbes,” or germs. They were feared for their large group attacks in the form of raids on markets, crowded street corners, or in common dwellings (cours-commune), generating violence that deeply shocked Ivoirians. The neighborhood of Abobo Gare is widely viewed as the birthplace of these gangs, though they quickly expanded throughout Abobo and later into wider Abidjan.

A local police commissioner describing the worst years of this crime crisis (circa 2012-2016) observed, “not an hour went by without a microbes alert.” The cycle of violence and perception of Abobo as a social ghetto was reinforced by gang leaders, some linked to the world of transport and organized crime, who found a seemingly infinite supply of vulnerable youth ready for recruitment. The government, criticized for its inaction against crime, responded by regularly launching large and confrontational police raids in Abobo. In private, local policemen, community leaders, and members of vigilance committees often criticized these operations as useless.

The consequences of the microbes crisis became unbearable for many communities in Abobo as the gangs wreaked havoc on residents during the 2010s. Two female shopkeepers who owned a school bookstore in a market in Abobo explained that during the various robberies and burglaries in their neighborhood, “we wanted to call the police, but they themselves [were] afraid of the microbes.” Consequently, the residents of Abobo’s sprawling neighborhoods mounted a collective response: vigilance committees.

Vigilance Committees in Abobo

Field research involving more than 100 interviews representing members of 6 vigilance committees sought to better understand the unfolding relationship between the vigilance committees, everyday citizens, police, and youth gangs in Abobo.

Vigilance committees typically trace their origins to a traumatic violent event related to the microbes that residents deemed intolerable, and which functioned as a tipping point. The heads of most vigilance committees are community youth leaders with support from well-known local figures or other bigwigs. Approximately 20 committees have operated in Abobo, each comprising between 50 and 200 members, though their membership fluctuates over time depending on the perceived intensity of the security threat. Armed with clubs and blended weapons, they operate in teams of around 10 members, organizing either patrols or checkpoints in their neighborhoods.

“Vigilance committees seek further bureaucratic formalization, advocating to administrative and political authorities for recognition and support.”

At the advent of the microbes crisis, the committees often employed violence after catching an alleged delinquent or violent criminal. This vigilante-style justice led to many human rights abuses. In some cases, committee leaders acknowledged that some apprehended individuals were killed. Generally, however, an alleged offender would spend the night in committee headquarters before its members attempted to mediate a resolution for the offense. If the offense could not be resolved through mediation, the individual would be escorted to the police station.

Each committee exhibits different degrees of institutionalization. The first organizational step typically formalizes an association in the neighborhood to represent the vigilance committee, providing loosely defined administrative practices and discourses. Sometimes vigilance committees seek further bureaucratic formalization, advocating to administrative and political authorities for recognition and support.

Often committee members employ overt symbols to signal their presence and increase their group’s capital within the community including whistles, armbands, badges, t-shirts, and sometimes hoods. Objects of magical or religious significance, such as talismans, also play an important role. Vigilance committee members use these types of cultural resources drawing upon shared beliefs to underscore their role in the community.

To finance their activities, many committees established fee-based ticket systems with phone numbers for emergencies, to which building managers or individuals could subscribe. While insufficient on their own, the ticket systems initially helped generate revenues. However, neighborhood donors, encouraged by community leaders, supply the principal financial backbone for the committees.

Vigilance Committee Contributions to Security

Vigilance committees in Abobo are generally perceived as having improved the security situation from its low point during the microbes crisis. In most cases studied, the committees have become key community stakeholders for local security. The challenge of urban crime remains far from resolved, as in practice many criminal groups and gangs have simply relocated to other parts of Abidjan. However, the improved security for Abobo’s communities is generally viewed as a victory.

“Efforts to establish vigilance committees represent collective action for a locally driven agenda.”

The committees’ connections to their communities are the source from which they derive their legitimacy and effectiveness. Committee members know their neighborhood and can thus operate well among their neighbors. Often times, the efforts to establish vigilance committees represent collective action for a locally driven agenda that has the support of community leaders. During the height of the crisis, for instance, Friday mosque prayers and Sunday church sermons became forums to gather support and find solutions to the traumatizing violence of rising urban crime in many communities.

The committees were not created for a particular political agenda, although after their success, some politicians did try to coopt them to gather popular support. In such instances, some committees pushed back against the politicians to maintain their independence and community standing. In other cases, the creation of vigilance committees served as a means for ambitious youth to climb the social ladder and gain influence in the community. Regardless, the popular legitimacy attributed to vigilance committees enabled them to better address neighborhood crime.

Initially, the popular appeal of the vigilance committees allowed them to fundraise sufficient resources from the community through the payment of dues for their activities. However, as security has improved, the population has become more reticent to pay. Therefore, local donors remain vital for the long-term financing of the committees. For example, when one committee declared that its mission was over and wanted to disband due to declining support, local imams and priests mobilized resources to sustain it.

New police officers in a neighboring borough of Abidjan. (Image: Video capture)

The police also benefitted from the committees’ activities. Police took advantage of the committees’ local knowledge and presence to regain a foothold in neighborhoods. This led to increased capacity and trust in police forces within the community. The leadership of certain local police commissioners was hailed by many stakeholders within and outside of Abobo, in part because of their supervision of the committees.

In Abobo, the committees that function the most effectively are those under the supervision of the local police. Vigilance committees and police have even invented some practices to streamline everyday work, such as the use of “small papers.” These reports made by victims to vigilance committees are transmitted to the police to facilitate the administration of their cases, simplifying the bureaucratic process of filing a police report and removing the need for victims to travel to the police station.

Another key factor contributing to the effectiveness of some vigilance committees relative to others is their understanding of the limits of coercive tactics. “Fighting enemies” such as the microbes within the community is not that simple and has consequences. Committee members often must negotiate with the family of delinquents as well as members of organized crime syndicates and gang leaders themselves.

“Vigilance committees reduce crime in general, but only with the help of local police and noncoercive tactics.”

To build long-term trust, more successful vigilance committees decrease their use of coercion. Seeking alternatives to violence, some committees aim to rehabilitate delinquent youth by integrating these gang members into the vigilance committees themselves. This leads to improved relations with the families of delinquents, but it also blurs the line between those who claim to fight for order and those perceived as troublemakers, raising issues of legitimacy.

The daily work of collaborative policing produces tensions in the social life of Abobo. Vigilance committees seeking to reintegrate stigmatized community youth at times find it difficult to offer redress to aggrieved citizens. Layered into the community’s social composition, vigilance committees reduce crime in general, but only with the help of local police and noncoercive tactics.

Police Collaboration and Negotiating Urban Order

Police in urban settings like Abobo must negotiate order with several interdependent actors including vigilance committees and other community leaders such as business owners or religious leaders. Sufficiently developed vigilance committees collaborate with the National Police at the local level, essentially extending the reach of the overstretched police force through their activities.

While the police officially deny the legality of vigilance committees, in practice at the neighborhood level, local police commissioners provide directives to tolerate, reject, collaborate, and sometimes participate in the organization of these community-based security groups. The discretion of these local bureaucrats is central to the relationship between the police station and the vigilance committees.

The 2011 conclusion of the Ivoirian civil war unlocked significant security assistance by international donors. The United Nations Development Program implemented security assistance programs that aimed to rebuild the degraded police infrastructure and simultaneously improve police-community relations through community policing programs under local government control. These programs established ethics advisory boards in each police station led by local superintendents. The ethics advisory boards meet monthly with community stakeholders to discuss police-community relations and security issues in their respective jurisdictions.

(Photo: Georges Hermann Njiale Njiale)

At least two police stations in Abobo use ethics advisory boards to manage neighborhood vigilance committees. In some cases, as the vigilance committees grew, they perpetrated human rights abuses contributing to new forms of insecurity in communities. In response, the police needed to monitor their activities and used the ethics advisory boards and their community policing programs to supervise these groups. These programs were not originally designed or intended for that purpose, but local police commissioners adapted them to their realities and needs.

Police departments have never achieved total control of the vigilance committees, however. Occasional abuses persist even with monitoring mechanisms in place. Sometimes, particularly in extortion cases, the closure of a committee has become necessary. Conversely, other vigilance committees are eager to participate in the ethics advisory boards and actively seek to improve relations with authorities, requesting, for example, human rights training.

Mobilization beyond Vigilance Committees to Tackle the Crisis

As the government tackled the microbes crisis, it began to recognize the limits of a coercive and militarized response to youth gangs. Strong support for President Alassane Ouattara’s government in Abobo helped to elevate the importance of the crisis and forced elected officials to pay greater attention to it. A relative increase in public investment has occurred in Abobo to improve infrastructure and social services. Political elites have even reached out to criminal “big men” in Abobo to improve relations between the transportation syndicate bosses and to reduce violent crime.

“Substantive answers to urban crime in Abobo require sustained political will to tackle systemic causes of insecurity.”

As some vigilance committees and civil society organizations advocate for and support social programs for gang members, the government has responded with resocialization programs. This national public policy of resocialization was partially inspired by the Ivorian Authority for Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration that operated from 2012-2015. Authorities rely on some of the most ambitious vigilance committees to implement this relatively innovative policy at the neighborhood level.

The Cellule de coordination de suivi et de réinsertion (CCSR) program sends young offenders mostly from Abobo in waves to a resocialization camp in a remote part of central Côte d’Ivoire, far from Abidjan. The program’s main objective, according to an official, was to “re-educate [the offenders], to inculcate civic and moral values proper to life in society.” Following their return to the community, participants had to choose between different trades and begin a mentoring program with an assigned tutor in technical fields such as sewing, carpentry, welding, or electricity.

Participants in this program emphasized the need to better align these occupations with their aspirations. Vigilance committee members highlighted that the poor funding for the mentoring program and weak monitoring of participants led many to become disillusioned. The long-term effectiveness of this program, and the long-term political will to sustain it, remains an open question, but their activities are ongoing.

A press conference on children in conflict hosted by the Cellule de coordination de suivi et de réinsertion (CCSR). (Image: Video capture)

NGOs such as Interpeace/Indigo have advocated for a more nuanced government response and have implemented their own violent youth reintegration programs.7 Experts such as Professor Francis Akindès have raised awareness on the issue of youth gangs by producing a documentary on what he called “the symbol of an economic apartheid.”8 These efforts illuminate that the substantive answers to urban crime in Abobo require sustained political will to tackle “systemic causes of insecurity,”9 including a lack of public services and the need to rein in major criminal actors.

Community policing initiatives like the Agence d’assistance à la sécurité de proximité in Senegal may offer further lessons on integrating vigilance committees.10 This parastatal agency was created in 2013 to assemble all Senegalese community-based security groups under one institution, with a philosophy of security governance and close cooperation with local governments. Integrating 10,000 members—almost as many as the police and gendarmerie forces of the country combined—they are mostly designed to undertake routine and petty crime policing tasks. Such efforts to formalize community-based security groups may offer fruitful insights on the next steps to combating urban crime.

Toward a Model of Collaborative Policing in African Cities

The reality of overstretched police forces in many African cities has made collaborative policing a basic fact of daily life. Abobo’s security arrangements offer some insights on the negotiated character of local-level urban order practices and how these practices may contribute to citizen-centered security. There is no one-size-fits-all formula of vigilance committees for enforcing order. Only under the right conditions do these efforts contribute to making security an actual public good. Policymakers and practitioners, consequently, require a better grasp over how to control and improve police collaboration with different forms of citizen participation.

Build community policing programs that establish oversight bodies for the supervision of collaborative policing groups. Community policing programs can be used to effectively supervise vigilance committees as well as foster trust among government, police, and community actors. But such programs and supervision of committees requires local ownership and organization to be effective. Successful vigilance committees in Abobo benefitted from the proactive and inclusive leadership of local police commissioners who adapted ethics advisory boards from community policing programs to monitor vigilance committees and engage the community.

The effective participation of police, civil society, and community leaders on the ethics advisory boards highlights the need for local authorities to include residents in the regulation of community-based security groups. Vigilance committees or other private citizen security ventures risk tearing at the social fabric of communities if they become the tools of local elites and their interests rather than the representatives of the communities’ security needs. The role of community members and leaders on ethics advisory boards helps to ensure that citizen participation in collaborative policing is regulated through democratic legislative and judicial means, which in turn protects marginalized populations by deterring human rights abuses.

Provide human rights training and integrate community-based security groups. Training on issues such as human rights and basic policing techniques is effective and desired by vigilance committee members and residents. Such formal training can facilitate a screening and certification of vigilance committee members. This may also serve to establish stronger partnerships between local police officials and designated members of the community, which in turn enhances security and accountability.

“Citizen security ventures risk tearing at the social fabric of communities if they become the tools of local elites and their interests.”

Local and national security initiatives should work through local oversight and regulatory bodies to formalize regular and mandatory trainings for community-based security groups. In time, such efforts might be combined to establish national-level collaborative policing initiatives like the Agence d’assistance à la sécurité de proximité in Senegal.

Tackle systemic factors linked to high crime rates and improve reintegration programs for gang members. Abobo’s most successful and ambitious vigilance committees quickly realized that coercive tactics and violent confrontations with youth gangs failed to address deeper community problems fueling the community’s urban crime. Using nonconfrontational tactics to engage with violent youth helped to prevent altercations and crime. It also built trust between vigilance committees and troubled community youth. Yet, vigilance committees do not represent a complete solution to the problems driving these youth to urban crime.

The Ivorian government’s resocialization programs present an opportunity to begin addressing these problems by offering opportunities and education to youth. Greater investment and organization in these programs is necessary, however. Sustained funding and mentoring of program participants would help to solidify the programs’ desired outcomes. Similar efforts in other contexts could be replicated, provided local considerations are also applied.

Routinely develop local analyses with local researchers to inform community policing programs. Only a fine-tuned and contextualized understanding of the social relations produced by collaborative policing can allow policymakers and officials to improve urban policing. Regular research into communities can help to facilitate accountability by investigating how community dynamics shift in response to community policing programs. These evaluations should be conducted with local authorities with deep knowledge of their communities and seek to go beyond the forum provided by ethics advisory boards or other regulatory bodies.

National-level programs and international support need to focus on disadvantaged neighborhoods when implementing police capacity building, with the importance of understanding the political economy and experiences of everyday policing by ordinary policewomen and men.11

Dr. Maxime Ricard is a West Africa researcher at the Institute for Strategic Research of the Military School (IRSEM, France). He is also associate researcher at the Centre FrancoPaix of the Raoul-Dandurand Chair in Canada.

Kouamé Félix Grodji is a Ph.D. candidate at Université Alassane Ouattara in Bouaké, Côte d’Ivoire.

Notes

- ⇑ Afrobarometer online analysis tool, “Round 7 2016/2018.”

- ⇑ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “Global Study on Homicide: Homicide trends, patterns and criminal justice response,” July 2019.

- ⇑ Maya Mynster Christensen and Peter Albrecht, “Urban Borderwork: Ethnographies of policing,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38, no. 3 (2020), 391.

- ⇑ Stephen Commins, “From Urban Fragility to Urban Stability,” Africa Security Brief No. 35, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 2018.

- ⇑ Oluwakemi Okenyodo, “Governance, Accountability, and Security in Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 31, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 2016.

- ⇑ Rebecca Tapscott, Arbitrary States: Social Control and Modern Authoritarianism in Museveni’s Uganda (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

- ⇑ Interpeace, “Reintegrating violent youths known as “microbes” to mitigate urban violence in Abidjan,” August 24, 2016.

- ⇑ Haby Niakaté, “Les enfants “microbes” sont un signe de l’apartheid économique qui s’installe en Côte d’Ivoire,” Le Monde, April 1, 2018.

- ⇑ Kasper Hoffmann, Koen Vlassenroot, and Karen Büscher, “Competition, Patronage and Fragmentation: The Limits of Bottom-Up Approaches to Security Governance in Ituri,” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 7, no. 1 (2018), 11.

- ⇑ Nabi Youla Doumbia, “Le problème du contrôle des groupes de vigilance en Afrique de l’Ouest francophone : Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Sénégal,” Bulletin FrancoPaix 4, no. 2, Centre FrancoPaix, February 2019.

- ⇑ Michel Thill, Robert Njangala, and Josaphat Musamba, “Putting everyday police life at the centre of reform in Bukavu,” Briefing Paper, Rift Valley Institute, March 2018.