Two years after Pierre Nkurunziza announced his intention to pursue a contested third term as President, the Burundi crisis continues to spiral. The February 2017 report of UN Secretary General António Guterres on Burundi warned that killings, enforced disappearances, gender-based violence, and the discovery of dead bodies continues at an escalating rate. Between October 2016 and February 2017, more than 200 disappearances were reported to the UN Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, compared to 77 between April and October 2016. There is also an upward trend in the discovery of dead bodies, including 22 that were discovered in January alone.

Many of these violations have been blamed on the Imbonerakure, a youth militia sponsored by the ruling CNDD-FDD party that operates outside the military chain of command and an increasingly central instrument to the regime’s power. An African Union fact finding mission has described violations by Burundi’s security forces as “pervasive, systematic, and massive.” And the UN Independent Investigation on Burundi has concluded that these actions were not by chance “or the result of a few bad actors, but stem from deliberate decisions and actions.”

Pierre Nkurunziza

The Secretary General’s report also warns about the frequent use of hate speech and incitement to ethnic violence, including the issuing of a questionnaire by the Ministry of Civil Service on November 8, 2016, requesting all public servants to state their ethnicity. Such incidents harken back to the ethnic profiling that presaged the 1972 and 1993 genocides.

Angered by the scrutiny, the Nkurunziza government on October 11, 2016, stopped cooperating with UN agencies, including the UN Human Rights Council and the International Commission of Inquiry on Burundi. It also rejected the deployment of AU monitors and declined to consent to a 5,000-person AU civilian protection force and 220 unarmed UN police observers.

An Expanding Crisis

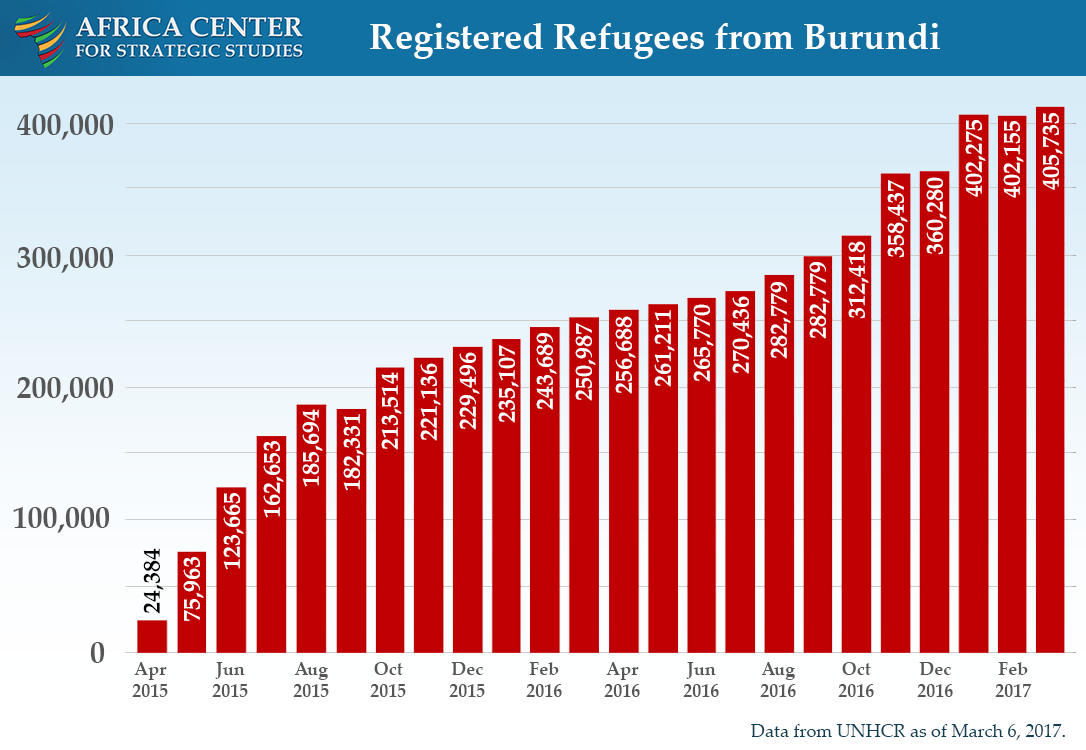

Despite claims by the government of Pierre Nkurunziza that the situation in Burundi has normalized, facts on the ground suggest otherwise. Over the past year, the number of Burundian refugees has nearly doubled to over 400,000. UNHCR expects this refugee figure to exceed half a million by the end of the year. Moreover, the death toll continues to rise. An International Rescue Committee survey of refugees in Tanzania found that 80 percent of the refugees interviewed said they witnessed one killing before fleeing. AU and UN investigations have corroborated prior reports of the existence of mass graves, with the UN warning of a new trend of people being killed in one location and buried elsewhere to avoid detection. Similarly, some detainees are being transferred from one province to another, sometimes several times over a short period, increasing the difficulty of recording casualties and the risk of enforced disappearances. This risk is amplified by an increase in recruitment and activities of the Imbonerakure, particularly in the provincial hotspots of Bururi, Cibitoke, Kirundo, Makamba, Muyinga, Rumonge, Rutana, and Ruyigi.

The humanitarian situation also continues to deteriorate. In 2016, the number of people in need of humanitarian assistance increased from 1.1 million to 3 million, or one quarter of the population, while those needing protection rose from 1.1 to 1.8 million. According to the UN Special Advisor on Burundi, the number of food-insecure Burundians rose from 730,000 in 2015 to 3 million in 2017.

Will the Arusha Accords Survive?

The signing of the Arusha Accords.

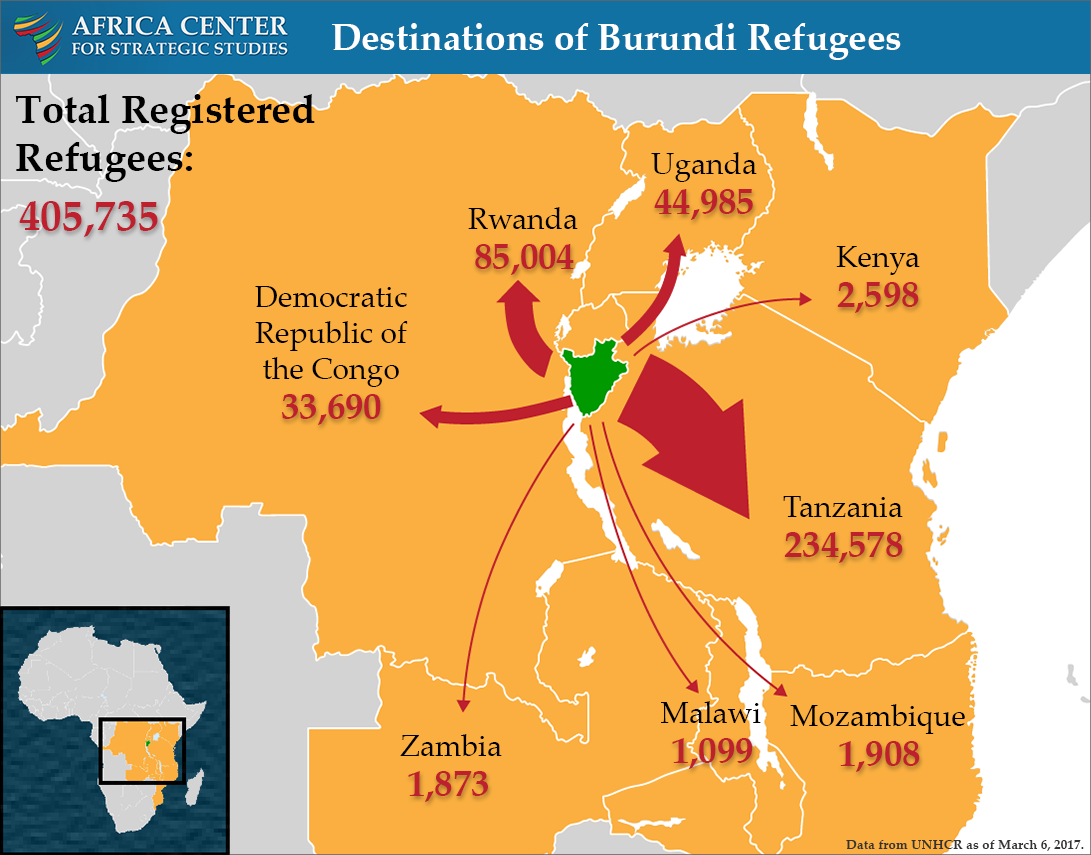

Brokered under the leadership of Julius Nyerere and Nelson Mandela, the Arusha Accords of 2000 ended 12 years of civil war and were hailed as Burundi’s best chance for peace and breaking the country’s cycles of mass atrocities dating back to independence. The Accords provided for power sharing, coalition-building, equitable participation in government, a system of checks and balances, and the integration of former enemies into a more representative military. Beyond their functional value, however, the symbolism of the Accords became a defining feature of a new Burundian national identity as a multiethnic society, an identity that resonated deeply with many, especially young Burundians. Moreover, the Accords were widely seen as guiding a period of unprecedented stability and progress in Burundi—until the crisis of 2015 erupted. Even then, despite the government’s use of ethnic incitement, the crisis has not been marked by community-based interethnic violence. Rather, violence has been systematically administered, largely by the government, as a means of intimidating opponents into cooperation. Opposition to Nkurunziza cuts across ethnic divides. Indeed, most members of the opposition coalition are Hutu, as are the vast majority of Burundian refugees in Tanzania, who now number 234,578.

Over the past two years it has become increasingly clear that undermining the Arusha Accords is a key objective of the Nkurunziza government.

Responding to growing concern about these proposed changes, CNDI said that Burundians supported the Constitution over the Arusha Accords—a view that echoed arguments made by the ruling CNDD/FDD in the months leading to Nkurunziza’s decision to contest a third term in April 2015. During that period, the ruling party introduced a bill to revise key provisions for power sharing, and political participation and representation. After the bill was defeated in Parliament, the government put the proposals to a referendum, but that too was defeated. It then tabled the proposals before the party’s central committee, a move that led to the defection of more than 100 top party officials to the opposition. Now, those same controversial proposals appear in CNDI’s recommendations, and the government has created a Constitutional Review Commission that will include them in a list of amendments.

The ruling CNDD/FDD’s unease with the Arusha Accords predates the current crisis. Since the civil war, some loyalists have held that the provisions for minority overrepresentation are unfair and should be reviewed. Others regularly take to social media to point out that CNDD/FDD was not a signatory to the Arusha Accords and is therefore not bound by its provisions. Still others suggest that the rules on ethnic balancing (60 percent Hutu/40 percent Tutsi in the civil service and 50/50 in the security sector) are outdated. Former South African president Thabo Mbeki, one of the chief architects of the Arusha Accords, has warned that Burundians “cannot afford to dismantle the Arusha Accords as the alternative is civil war.” More recently, UN Secretary General Guterres cautioned that the proposed amendments run the risk of deepening the crisis.

The Military is Refashioned

Once seen as a crowning success of Arusha, the army’s professionalism increased steadily since the Arusha Accords were signed thanks to years of international training and participation in peace missions. As a result, the army (unlike the police) came to be seen as a multiethnic, apolitical body upholding the constitution and not any given political party. The military’s experience was on full display during the first few months of the crisis when troops deployed to quell riots refused to fire on the crowds and instead positioned themselves between protestors and the police and the Imbonerakure, even taking casualties in the process.

Once seen as a crowning success of Arusha, the army’s professionalism increased steadily since the Arusha Accords were signed thanks to years of international training and participation in peace missions. As a result, the army (unlike the police) came to be seen as a multiethnic, apolitical body upholding the constitution and not any given political party. The military’s experience was on full display during the first few months of the crisis when troops deployed to quell riots refused to fire on the crowds and instead positioned themselves between protestors and the police and the Imbonerakure, even taking casualties in the process.

However, the government’s constitutional review has gone hand in hand with sweeping changes in the military. A new Senate bill renames the army, reorganizes its domestic command structures, and creates multiple services, including reserve units and a national youth service. Many are fearful that auxiliary forces will provide cover for the regime to incorporate the Imbonerakure and other militias into the regular forces.

Military reorganization is evidently an effort to increase the regime’s control over the army’s apolitical posture.

A Renewed Peace Plan Required

Despite the highly polarized environment, opposition to Nkurunziza remains multiethnic, and the population has so far resisted the government’s ethnic incitement. There is also broad acceptance among Burundians that the Arusha principles offer the best path to peace, justice, and accountability. This can only be realized, however, through a renewed peace plan that builds on the Arusha Accords and is inclusive and participatory. Any new peace plan, moreover, will require strong external engagement, especially by the East African countries that have absorbed the over 400,000 refugees and could be drawn into Burundi’s growing instability. Just as with the Arusha Accords, progress will only be achieved by the consistent application of persuasive and coercive measures by external partners and a shared set of expectations among regional leaders who can speak with one voice.

Despite the highly polarized environment, opposition to Nkurunziza remains multiethnic, and the population has so far resisted the government’s ethnic incitement. There is also broad acceptance among Burundians that the Arusha principles offer the best path to peace, justice, and accountability. This can only be realized, however, through a renewed peace plan that builds on the Arusha Accords and is inclusive and participatory. Any new peace plan, moreover, will require strong external engagement, especially by the East African countries that have absorbed the over 400,000 refugees and could be drawn into Burundi’s growing instability. Just as with the Arusha Accords, progress will only be achieved by the consistent application of persuasive and coercive measures by external partners and a shared set of expectations among regional leaders who can speak with one voice.

Africa Center Expert

Joseph Siegle, Director of Research

Additional Resources

- Joseph Siegle, “Congressional Testimony: The Political and Security Crises in Burundi,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 10, 2015.

- Nicole Ball, “Lessons from Burundi Security Sector Reform Process,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 29, November 2014.

- Thierry Vircoulon, “Insights from the Burundi Crisis II: An Army Divided and Losing Its Way,” International Crisis Group, October 2, 2015.

- Paul Nantulya, “Stopping the Spiral in Burundi,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 28, 2016.

- Paul Nantulya, “Why the Arusha Accords Are Central,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 5, 2015.

More on: Conflict Prevention or Mitigation Democratization Identity Conflict Security Sector Governance Burundi Rule of Law