In Nigeria’s recent campaign to contain an Ebola outbreak within its borders, there was little margin for error. Scientists had warned in a September 2014 study that the probability that Ebola would spread internationally would increase if the virus were not contained in Nigeria due to the country’s extensive international linkages. “Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone are not well connected outside the region,” said the study. “Nigeria, in contrast, being the most populous country in West Africa with more than 166 million people, is well connected to the rest of world.” Despite numerous competing priorities and resource limitations, Nigeria succeeded in halting the spread of Ebola within its borders.

“If a country like Nigeria, hampered by serious security problems, can do this—that is, make significant progress towards interrupting polio transmission, eradicate guinea-worm disease and contain Ebola, all at the same time,” said WHO Director-General Margaret Chan, “any country in the world experiencing an imported case can hold onward transmission to just a handful of cases.”

Photo: Zach Orecchio.

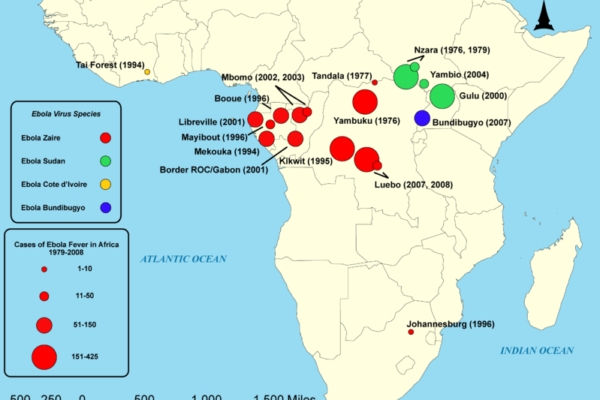

Fortunately for Nigeria and the rest of the region, the country’s Ebola response team did not have to develop their strategy from scratch. Two dozen Ebola outbreaks have been contained since the discovery of the virus in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1976. Along the way, numerous African states have identified and refined best practices for combating the disease. Uganda, for example, pioneered ways to act early and aggressively to identify and respond to possible instances of Ebola when the virus emerged in that country in late 2000.

Within days of the first confirmed Ebola case in 2000, Ugandan authorities worked with international and regional partners to establish checkpoints at airports and borders. Medical and community surveillance teams were promptly set up. Healthcare workers, along with nominated community leaders, were trained to identify the signs and symptoms of the virus. Medical workers banded together with the military, police, and volunteers from civil society to form mobile response teams that could rapidly deploy to investigate and respond to suspected cases. Targeted and persistent public information campaigns, in part modeled after efforts to educate Ugandan citizens about HIV/AIDS, raised awareness about the virus.

Ugandan authorities swiftly established robust protocols for contact tracing—identifying everyone who has been in contact with a sick Ebola patient. “Contact tracing finds cases quickly so they can be isolated to stop further spread,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Contacts are watched for signs of illness for 21 days from the last day they came in contact with the Ebola patient,” the CDC said. “If the contact develops a fever or other Ebola symptoms, they are immediately isolated, tested, provided care, and the cycle starts again—all of the new patient’s contacts are found and watched for 21 days.”

Nigeria’s first Ebola patient, an American of Liberian descent, collapsed upon arrival at the airport in Lagos, the country’s largest city and economic hub, on July 5, 2014. Prior to his flight, he had left a treatment facility in Liberia against medical advice. After arriving at a Lagos hospital, the patient reportedly denied having had exposure to the virus. Aware of the dangers of discharging him, the hospital refused to let him leave. The patient tested positive for Ebola and eventually died five days later.

Photo: CDC Global.

As soon as it discovered the presence of a sick Ebola patient, Nigerian authorities declared a national public health emergency, enabling Nigeria’s Ministry of health to establish the Ebola Emergency Operations Center (EOC), a “war-room” that fostered collaboration between Nigerian government officials, medical professionals, and international advisers. This was a crucial step in allowing the country to tap into the resources and experience of international and regional partners.

Doctors Without Borders and WHO trained Nigerian healthcare workers to respond to possible Ebola cases as authorities embarked on an extensive contact tracing effort. Within days of the first reported case of Ebola in Nigeria, the response team tracked down more than 900 people, including many who boarded the same flight as the patient. A vigorous 21-day monitoring process went into effect. Additional screening was put in place at all entry and exit ports in the country. Monitored persons who became symptomatic during the 21-day period were immediately isolated and put on treatment regimes. Health authorities in Nigeria conducted over 19,000 face-to-face visits during the monitoring period.

The response team identified 20 individuals that had been infected with the virus, including numerous healthcare professionals that had treated the original patient. Eight patients died, including the doctor who identified the country’s first Ebola patient. Despite these setbacks, Nigeria successfully prevented the virus from spreading beyond control. By October 20, 42 days had passed since an infection occurred in the country, and Nigeria was certified by WHO as Ebola-free.

Although Nigeria’s first Ebola scare has been contained, authorities remain vigilant, continuing to screen for potential cases at airports and border crossings. The Nigerian Medical Association (NMA) has even called for the government to stand up “Community Ebola Surveillance Units” and to establish isolation facilities across the country.

More on: Ebola Health & Security