FARDC soldiers patrol near Goma after an attack by M23 rebels. (Photo: AFP)

The precipitous escalation of the security crisis in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) risks reigniting interstate conflict in the Great Lakes region. The myriad actors and interests involved, however, often defy easy analysis. To help clarify what is driving the worsening security situation, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies compiled this explainer drawing on the insights of multiple experts including:

- Kwezi Mngqibisa, a senior research fellow at the University of Johannesburg who previously worked on South African efforts to broker peace between Rwanda and the DRC as part of the Lusaka Agreement

- Claude Gatebuke, the director of the African Great Lakes Action Network

- Cedric De Coning, a co-director at the Norwegian Institute for International Affairs and former advisor to the African Union’s Peace Support Operations Division

- Paul Nantulya, a research associate at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies who also worked on the South African-led Lusaka Agreement peace process and the Inter-Congolese Dialogue

- Ambassador Said Djinnit, the former Special Envoy of the United Nations Secretary General for the Great Lakes Region contributed to the analysis.

When did the current crisis begin?

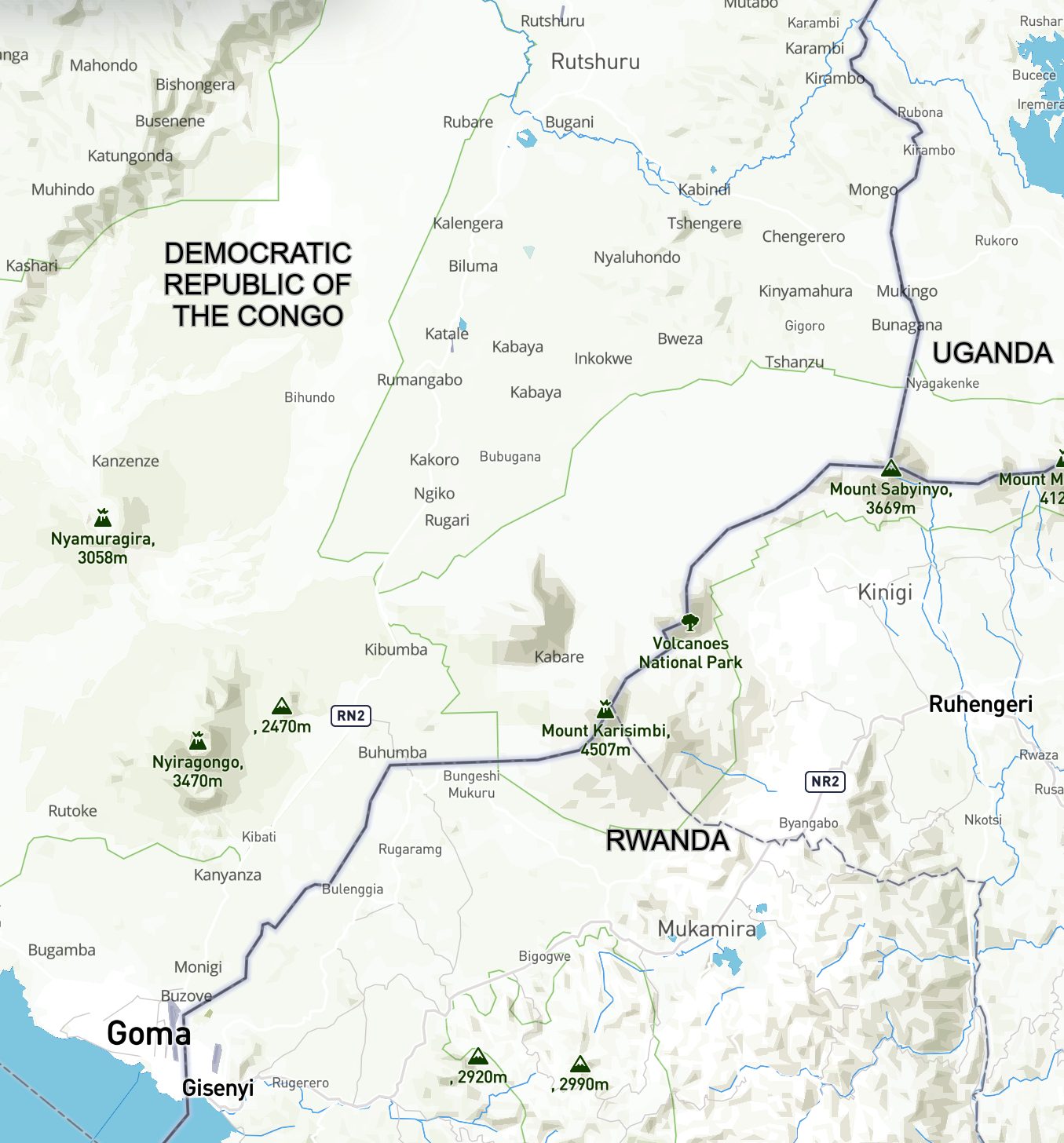

The current crisis erupted in November 2021, when the largely defunct March 23 Movement (M23) militant group carried out lightning strikes on military positions of the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) in the villages of Chanzu and Runyonyi in North Kivu Province, just west of the Ugandan and Rwandan borders. This occurred the same month that Ugandan forces were deployed to the province to pursue the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a Ugandan rebel group that also operates in North Kivu and Ituri. In October and November 2021, Uganda had been a target of suicide bomb attacks that President Yoweri Museveni blamed on the ADF.

Source: Kivu Security Tracker

By March 2022, M23 had seized key parts of Rutshuru territory, bordering Uganda and Rwanda. In May, they overran the Rumangabo military base, FARDC’s largest military installation in North Kivu. They then pushed south toward the provincial capital, Goma, and across Rwanda’s border city of Gisenyi. In June, another M23 prong operating farther north overran the border city of Bunagana, forcing Congolese soldiers to flee to Uganda.

All this has come as a surprise given the 10-year lull in M23 activities. Between March and November 2013, M23 suffered numerous defeats at the hands of the Congolese military, the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), and the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) consisting of Tanzanian, Malawian, and South African troops. That March, one cohort of hundreds of fighters fled to Rwanda. Its leader, John Bosco Ntaganda, a.k.a. “The Terminator,” handed himself over to the U.S. Embassy which transferred him to the International Criminal Court to face war crimes charges.

“The longstanding rivalry between Uganda and Rwanda in the DRC and the Great Lakes region is a key driver of the current crisis.”

In November 2013, another cohort of some 1,500 M23 fighters—the remainder of the rebel group—surrendered to the Ugandan military after their strongholds were overrun by UN and FARDC forces. A month later, some 1,374 were dispatched to Uganda’s Bihanga Military Training School for demobilization. By 2017, however, only some 390 were still at Bihanga. There was no official explanation as to why or to where the majority of the ex-combatants had gone.

The DRC has blamed Rwanda for reorganizing and arming the latest insurgency. The UN Security Council’s Group of Experts on the DRC has previously implicated Rwanda of backing M23. Originally part of the Congolese military, M23 is dominated by Congolese Tutsis. It claims it wants to protect Tutsis against militant Hutu groups, including the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), which counts among its forces elements accused of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

Some of M23’s top commanders once served in the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF), notes Claude Gatebuke. The RPF leadership—including President Paul Kagame and his former Army Chief of Staff, James Kabarebe—once served in Uganda’s military and were part of the rebellion that brought Yoweri Museveni to power in 1986. They then occupied top positions in Rwanda’s military and government after seizing power there with Uganda’s support in 1994. When both countries invaded the DRC in 1996 to remove Mobutu Sese Seko and install Laurent Kabila, a similar pattern transpired with James Kabarebe becoming Chief of Staff of the DRC’s military. However, when Kabila fell out with Uganda and Rwanda, the two countries sponsored another rebellion in the DRC. Over time, Uganda and Rwanda fell out and started supporting proxy forces against each other.

Ugandan soldiers patrolling the Virunga National Park in December 2021 following attacks by the ADF. (Photo: AFP)

This history of recycling officers among Rwanda, Uganda, and the DRC—and the use of proxies—has implications for the current crisis. Kabarebe was identified by the UN in 2012 as the chief mastermind of M23. In addition to Rwanda, the UN has implicated Uganda with aiding M23. Following the capture of Bunagana in June 2022, the Speaker of the DRC National Assembly and key ally of President Felix Tshisekedi, Christophe Mboso, condemned Uganda and moved a motion to suspend all military and economic agreements between the two countries. While Ugandan security officials have accused Rwanda of supporting the M23 attack in Bunagana to frustrate UPDF operations against the ADF, Rwanda alleges Uganda is using M23 elements to threaten Rwanda.

In response to the rapid deterioration in the eastern DRC, the East African Community decided in June 2022 to deploy a regional force under Kenyan command to restore stability.

What explains M23’s resurgence?

The longstanding rivalry between Uganda and Rwanda in the DRC and the Great Lakes region is a key driver of the current crisis. There are immediate and longer-term reasons for this. With regard to the latter, there is a profound level of mistrust at all levels—between the DRC and its neighbors, particularly Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi—as well as between all of these neighbors. According to Claude Gatebuke, “unless the underlying problems between Rwanda and Uganda in particular are addressed, we are unlikely to see the M23 problem resolved in a satisfactory way even if a regional force is deployed. This is a lesson we have learned from previous Ugandan and Rwandan interventions in Congo.”

As Kwezi Mngqibisa notes, the cohorts of M23 fighters who withdrew to Rwanda and Uganda remain antagonistic toward one another—making them convenient tools for the two regional rivals who have fought numerous proxy wars for spheres of influence, especially in North Kivu. The region is poorly governed but rich in minerals like gold, coltan, tantalum, and diamonds. “Uganda and Rwanda have backed rival movements in Congo ever since they clashed militarily in Kisangani in the late 1990s,” Mngqibisa adds. “There is a larger conflict system where the Ugandan and Rwandan contest for supremacy almost always coincides with an uptick in violence in eastern DRC. We may be witnessing this all over again as the current crisis escalates.”

Jason Stearns agrees with the analysis that Uganda and Rwanda have started down the path of renewed proxy warfare in Congo. Besides allowing Ugandan troops to operate in North Kivu, DRC President Tshisekedi approved a plan in 2021 to construct roads linking the two countries. One set of road projects runs from Kasindi to Beni and Butembo, and the other from Bunagana to Rutshuru and finally Goma. “The timeline of the [military] operations and road construction have been connected,” Stearns explains. “The UPDF officially initiated attacks against the ADF on November 30, 2021; road construction started just a few days later, on December 3, 2021.” Notably, the memorandum of understanding (MOU) on road construction was part of the military agreement between the two nations and is therefore classified and unavailable for public comment. It was signed by the chiefs of staff of the two militaries, not their ministries of finance or planning.

Click image to enlarge. (Source: Congo Research Group/Ebuteli)

The MOU also allows the UPDF to protect the road works as well as the staff and equipment. Notably, Uganda contributes 100 percent of the funding. Forty percent comes from its budget and the rest from Dott Services, the Ugandan firm chosen to do the construction. The deployment of Ugandan forces into North Kivu and the construction of a Ugandan-funded road network protected by the UPDF and extending all the way to Goma—at Rwanda’s doorstep—were viewed as unfriendly acts in Kigali. In a speech before Parliament in February 2022, Rwandan President Kagame warned that the threats emanating from North Kivu were grave enough to warrant a Rwandan deployment without the DRC’s approval: “We do what we must do, with or without the consent of others.”

Jason Stearns observes that Rwanda’s growing sense of isolation, stemming from tensions with Uganda, cannot be overstated. Kampala and Kigali view each other’s gains as setbacks. President Tshisekedi’s earlier effort to permit Uganda, Burundi, and Rwanda to operate jointly in eastern DRC under Congolese supervision failed due to bickering between Uganda and Rwanda. Neither wished to see the other extend its influence in North Kivu.

“Neither [Uganda nor Rwanda] wished to see the other extend its influence in North Kivu.”

Eventually Tshisekedi pursued bilateral agreements with both of his neighbors. In addition to the agreement struck with Uganda discussed above, in March 2021, he worked out a deal with Rwanda on joint operations. A similar deal was reached with Burundi in July, setting the stage for the deployment of the Burundi military into South Kivu to pursue Burundian rebels. However, while the Ugandan and Burundian deployments went ahead as planned, the security deal between Rwanda and the DRC remains on ice—a development many in Kigali believe was instigated by Kampala. All told, Uganda’s escalating military and economic engagements in the DRC and Rwanda’s heightened threat perceptions have inflamed their rivalry—providing the context in which M23 has rebounded after being dormant for nearly a decade.

What role do economic and commercial interests play?

M23’s sudden resurgence is also tied to overlapping economic and business interests. “Rwanda and Uganda can claim to have legitimate security interests in Congo,” says Mngqibisa. “However, they also have huge financial interests there—particularly extractives—which contributes to their rivalry.” The arc extending from Bunagana on the Uganda border, through Kanyabayonga, to Goma on the Rwanda border, covers a lucrative mining belt containing some of the world’s largest deposits of coltan, which is used in almost every electronic device. The DRC is also the world’s leading producer of cobalt, a key ingredient in electric car batteries which are currently in high demand.

A mine worker in South Kivu. (Photo: Enough Project)

There is ample evidence to suggest that Ugandan- and Rwandan-backed rebel factions—including M23—control strategic but informal supply chains running from mines in the Kivus into the two countries. Insurgents use proceeds from the trafficking of gold, diamonds, and coltan to buy weapons, recruit and control artisanal miners, and pay corrupt Congolese customs and border officials as well as soldiers and police. Significant violence is also involved in these illicit operations as various rebel factions often fight one another for control of the mines and transport routes.

The nexus of conflict, minerals, rebels, and foreign backers has bedeviled Congo for decades. A critical part of the problem is that Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi are exporting things they do not produce, meaning a lot of smuggling is taking place as noted by successive UN investigations. In February 2022, the International Court of Justice ordered Uganda to pay $325 million to the DRC for its role in the conflicts there between 1998 and 2003, which include the deaths of thousands of civilians in the Ituri region, the bankrolling of rebel groups, and the looting of gold, diamonds, and timber. Rwanda has also been mentioned repeatedly in UN reports for profiting from minerals smuggled from the DRC to fund rebel groups and bolster its own exports.

Both deny these charges. However, some of the evidence shows up in their export earnings. For example, gold is now Uganda’s largest export, yet most of it comes from the DRC. In similar vein, 40 percent of the world’s coltan was officially produced in the DRC in 2019. However, large quantities are reportedly trafficked into Rwanda and exported from there. This pattern is replicated elsewhere in the region. Therefore, while the DRC is recognized as the world’s largest coltan producer, Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi rank third, ninth, and eleventh, respectively, even though they only have limited known deposits themselves.

Coltan from a Congolese Mine. (Photo: Responsible Sourcing Network)

The vast expanse of ungoverned space stretching from Uganda to Rwanda and Burundi provides an ideal geography for illicit trading. UN reports show that while most of the DRC’s trafficked coltan winds up in Rwanda, a significant amount is also diverted to Uganda via Bunagana and Rutshuru in North Kivu, while some ends up in Burundi via Uvira in South Kivu. All told, the evidence suggests that the DRC’s eastern neighbors—especially regional rivals Uganda and Rwanda—want exclusive access to mining operations in the Kivus. This, in turn, makes proxy violence more likely.

In November 2020, Dott Services, the Ugandan firm that is co-financing and building the road networks linking Uganda and the DRC, established a joint venture with the Congolese mining parastatal, Société Aurifère du Kivu et du Maniema (Sakima), the result of which gave it access to strategic mines in Maniema Province rich in tin, tantalum, gold, and tungsten.

Dott Services owns 70 percent of the venture while Sakima holds the rest. Under the contract, Dott Services will also build a factory to process minerals and precious metals in addition to infrastructure projects. Dott Services is widely viewed as being close to Uganda’s first family and other influential actors—highlighting the high stakes involved in the country’s engagements in the DRC.

“These counteraccusations underscore the role that financial and economic interests play in the resurfacing of M23.”

Rwanda has a foot in the door, too. In June 2021, Presidents Kagame and Tshisekedi signed an agreement under which Dither Ltd., a firm widely viewed as close to Rwanda’s military, will refine the gold produced by Sakima “to deprive the armed groups of the revenue from the sector.” This puts Rwanda in a strategic position to control the entire supply chain—a move many believe rankled Kampala. However, the deal was suspended in early June 2022 over claims by the DRC that Rwanda was backing M23’s resurgence.

Ugandan officials claim that Rwanda became more determined to revive M23 after its economic ventures in the DRC were thrown into disarray. During the M23 raid in Bunagana on March 23, 2022, Ugandan soldiers intervened to protect Dott Services’ assets and staff. The narrative in Kampala is that the attack was carried out by the “Rwandan wing” of M23 as part of a plot by Rwanda to disrupt Uganda’s economic ventures in the DRC. The narrative in Kigali is that the attack was carried out by M23 elements controlled by Uganda as a ploy to seize the border town, which is an important staging area for Dott Services’ operations. These counteraccusations underscore the role that financial and economic interests play in the resurfacing of M23 which feeds off the Uganda-Rwanda rivalry.

What are the risks of interstate conflict?

The eastern DRC is a tinderbox because Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi each face armed rebellions all based in this region. This amplifies the risk of interstate conflicts. Rwanda has been more explicit in its threat to intervene militarily in the DRC than it has been in recent years. It accuses the FARDC of fighting alongside the FDLR and being indifferent to Kigali’s security fears. However, these threats have been levied before. What makes them more pronounced this time around is the presence of Ugandan troops in North Kivu, the closeness among Uganda, Burundi, and the DRC, and the breakdown of the rapprochement between Presidents Kagame and Tshisekedi.

In June 2022, Rwanda and the DRC accused each other of firing rockets across their shared border. The DRC authorities also alleged that Rwanda deployed hundreds of soldiers in disguise on Congolese soil. On June 17, the DRC closed its border with Rwanda after a Congolese soldier was shot dead on Rwandan soil after an alleged incident with Rwandan border guards. “Without a vigorous confidence-building process between the two sides, a wider interstate conflict is a strong possibility,” says Claude Gatebuke. “That would likely draw in Uganda and possibly Burundi on the side of the DRC.”

“Without a vigorous confidence-building process between the two sides, a wider interstate conflict is a strong possibility.”

Uganda and Rwanda were on a war footing as recently as 2019. They reopened their border in January 2022, after a 3-year closure, but tensions remain palpable and have been worsened by Uganda’s recent moves in the DRC. However, rather than launching direct attacks on each other, the two countries appear to have shifted into a familiar pattern of fighting proxy wars. This means that the prospects of a general disarmament in the region—particularly of M23—are likely to be frustrated unless these differences are resolved.

The risk of interstate conflict is also increased by failed disarmament efforts. In October of 2017, the 13 signatory countries and 4 guarantor institutions (UN, AU, ICGLR and SADC) to the Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework Agreement for the DRC and the region decided to repatriate ex-combatants from the FDLR and M23 by October 2018. “This deadline came and went without any significant action,” explains Gatebuke, who calls the disarmament process a “monumental failure” whose consequences are now evident. Notably, very few of the M23 cohorts that fled to Uganda and Rwanda in 2013 have been repatriated to the DRC.

Under the terms of the 2013 peace deal between the DRC government and M23, blanket amnesties were given to those who renounced rebellion unless they are indicted for war crimes. M23 leaders often accuse the DRC government of reneging on this agreement. Many believe that M23’s recent attacks might also be aimed at applying pressure on the Tshisekedi government to press their case. “We also have to question the rationale of hot pursuit by Congo’s neighbors,” says Gatebuke. “Uganda and Rwanda have operated in the DRC before with Congolese permission but have failed to dislodge their respective armed groups. One wonders if this is not merely a pretext to continue plundering the country and carving out areas of influence.”

The resurgence of M23 has also brought the region’s complex and explosive ethnic dynamics to the fore. Its leaders and fighters are predominantly Tutsi, a community whose citizenship status remains contentious. The uprising against the late dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, was triggered in part by his decision to strip the Banyamulenge—Congolese of Rwandan extraction—of their citizenship. They constituted the bulk of the force that overthrew Mobutu and installed Laurent Kabila in 1998 with Ugandan and Rwanda backing. When Uganda and Rwanda fell out with Kabila in 1999, they again formed the bulk of the rebellion put together to remove him, under the banner of the Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD). When Uganda and Rwanda fell out with each other, the RCD split into two factions supported by either side. This trend has continued and is evident in M23’s internal dynamics.

A village in the hills of North Kivu. (Photo: Monusco)

The Banyamulenge are widely referred to pejoratively as “Rwandophones” and are often targeted in sectarian violence when tensions with Rwanda reach fever pitch. Indeed, the protests against M23 quickly turned xenophobic, with Tutsis in particular being singled out for mistreatment and hate speech. During a protest in Kisangani on June 14, 2022, a senior Congolese army officer hailing from the Tutsi community was brutalized by angry protestors. The following day, the High Council of Defense, the DRC’s National Security Council, instructed the Interior Ministry and Police to take all “necessary measures to avoid stigmatization and manhunting.”

However, the xenophobic violence has continued, with many businesses and properties belonging to Rwandans and Congolese Tutsis being ransacked in waves of anti-Rwanda protests sweeping the eastern DRC. Protestors are also burning images and effigies of Presidents Kagame and Museveni and ransacking Ugandan and Rwandan businesses.

In the past, Congolese leaders have whipped up xenophobic sentiments to increase their electability. This, however, can be a double-edged sword. Anti-Rwandan and anti-Ugandan sentiments in the DRC are widespread owing to their legacy of invasions. Aware of these misgivings, the DRC government did not publicize its security deals with Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi and has not made its MOU with Uganda public. The decision may cost Felix Tshisekedi crucial support as he gears up for re-election in 2023.

How can tensions be de-escalated and who is credible enough to bring this about?

The Kenya government has injected new impetus for de-escalation by pushing for the deployment of a multinational East African Community (EAC) force to North and South Kivu, and Ituri. However, the composition of this force matters greatly given Congo’s frictions with its neighbors. The best way to win the confidence of Congolese citizens is to exclude countries that have participated directly or indirectly in invading and occupying parts of the DRC and conducting military operations there—namely, Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi. The Force Intervention Brigade (FIB), which started out as a coalition composed of Malawi, Tanzania, and South Africa in 2013 and became part of MONUSCO in 2020, offers a model for the EAC that could be replicated.

The FIB is widely seen as a good model to follow for two reasons: it was militarily effective, and more importantly, its members had no vested interests in the DRC and were therefore not seen by Congolese as part of the problem. However, it lost its unity of command when it was incorporated into MONUSCO. Furthermore, there is a feeling within EAC that after defeating M23, the FIB did not show the same determination to confront FDLR and ADF. Notably, significant sections of Congolese civil society and parliamentarians have voiced opposition to the EAC force due to the legacy of repeated invasions by the DRC’s neighbors. The EAC mechanism could benefit from a wider process involving the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (IGCLR), which might include countries like South Africa. This way, the endeavor could be a partnership between the EAC and Southern African Development Community (SADC), which is useful since the DRC is a member of both.

Police in Goma facing demonstrators protesting Rwandan involvement in the region, June 15, 2022. (Photo: AFP)

The Congolese government may also set conditions for the EAC force, including its objectives, areas of operation, and duration. These should be presented to Parliament for public input, approval, oversight, and regular monitoring to ensure that Congolese citizens are brought on board and have a say.

President Tshisekedi can also leverage his position as the newest member of the ICGLR to strengthen its oversight functions, particularly in terms of collecting evidence of foreign support for rebels in the east.

“Given that the DRC’s problems are political, the EAC will need to recognize that military solutions alone are insufficient.”

Given that the DRC’s problems are political, the EAC will need to recognize that military solutions alone are insufficient. There is need for an inclusive and even-handed political process to disarm and reintegrate rebel groups. By necessity this must incorporate measures to ensure the proper oversight and stewardship of the DRC’s natural resources.

Cedric De Coning notes that there needs to be a multitrack mediation process with an internal aspect that resolves political issues within the DRC, and an external one that tackles regional differences among neighbors. “This needs to be done in the context of regional heads of state.”

A “Wall of Hope” in Beni, North Kivu. (Photo: Monusco)

“This would borrow from the 1999 Lusaka Agreement peace process that provided a mechanism to resolve tensions among countries that had entered Congo on different sides and facilitate their withdrawal in order to support the Inter-Congolese Dialogue” says Mngqibisa. “One device we worked on as part of that process, and which could be replicated by EAC, was the Third Party Verification Mechanism created by South Africa. It promptly investigated complaints like the ones we are hearing from Rwanda and the DRC and determined their veracity at every step.

“Sometimes rebels are not the best agents at articulating grievances, but it is possible to engage in mediation to address the larger issues they mobilize around,” says Gatebuke. Senior UN diplomats involved in previous negotiations say the M23 was difficult to engage since it had been in rebellion for so long that it had become a way of life. Despite this, the UN eventually managed to bring them to the table in Kinshasa.

The takeaway for the current crisis is that political mediation is vital because, ultimately, the DRC’s challenges are political and do not lend themselves solely to military solutions.

Additional Resources

- Congo Research Group and Ebuteli, “Uganda’s Operation Shujaa in the DRC: Fighting the ADF or Securing Economic Interests?” NYU Center on International Cooperation, June 2022.

- International Crisis Group, “Easing the Turmoil in the Eastern DR Congo and Great Lakes,” Briefing No. 181, May 25, 2022.

- Paul Nantulya, “A Medley of Armed Groups Play on Congo’s Crisis,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 25, 2017.

- Jason Stearns, Judith Verweijen, and Maria Eriksson Baaz, “The National Army and Armed Groups in the Eastern Congo: Untangling the Gordian knot of Insecurity,” Rift Valley Institute, 2013.

- Paul Nantulya, “The Ever-Adaptive Allied Democratic Forces Insurgency,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 8, 2019.

More on: Democratic Republic of the Congo Rwanda Uganda