English | Français

Members of the Congolese Red Cross and Civil Protection bury dozens of victims in a cemetery in Goma on February 4, 2025. At least 2,900 people were killed during M23’s seizure of the capital on North Kivu. (Photo by ALEXIS HUGUET / AFP)

The fall of Goma to the March 23 Movement (M23) rebels has sent shock waves through the region and risks triggering a wider regional war. Memories remain fresh of the devastating Congo Wars of the late 1990s and early 2000s in which 7 African militaries intervened, and an estimated 5.4 million Congolese died.

The development is particularly alarming because it is widely recognized that M23 is backed by the Rwanda Defense Force (RDF) in support of Rwandan interests in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In addition to the estimated 6,000 M23 troops, there are approximately 4,000 Rwandan forces forces currently in the DRC. There is also evidence from UN investigations that M23 is receiving support from Uganda. Reports indicate that Congolese troops, government-aligned militias known as Wazalendo, and foreign mercenaries have surrendered to RDF troops in the DRC.

The fall of Goma to March 23 Movement (M23) rebels has sent shock waves through the region and risks triggering a wider regional war.

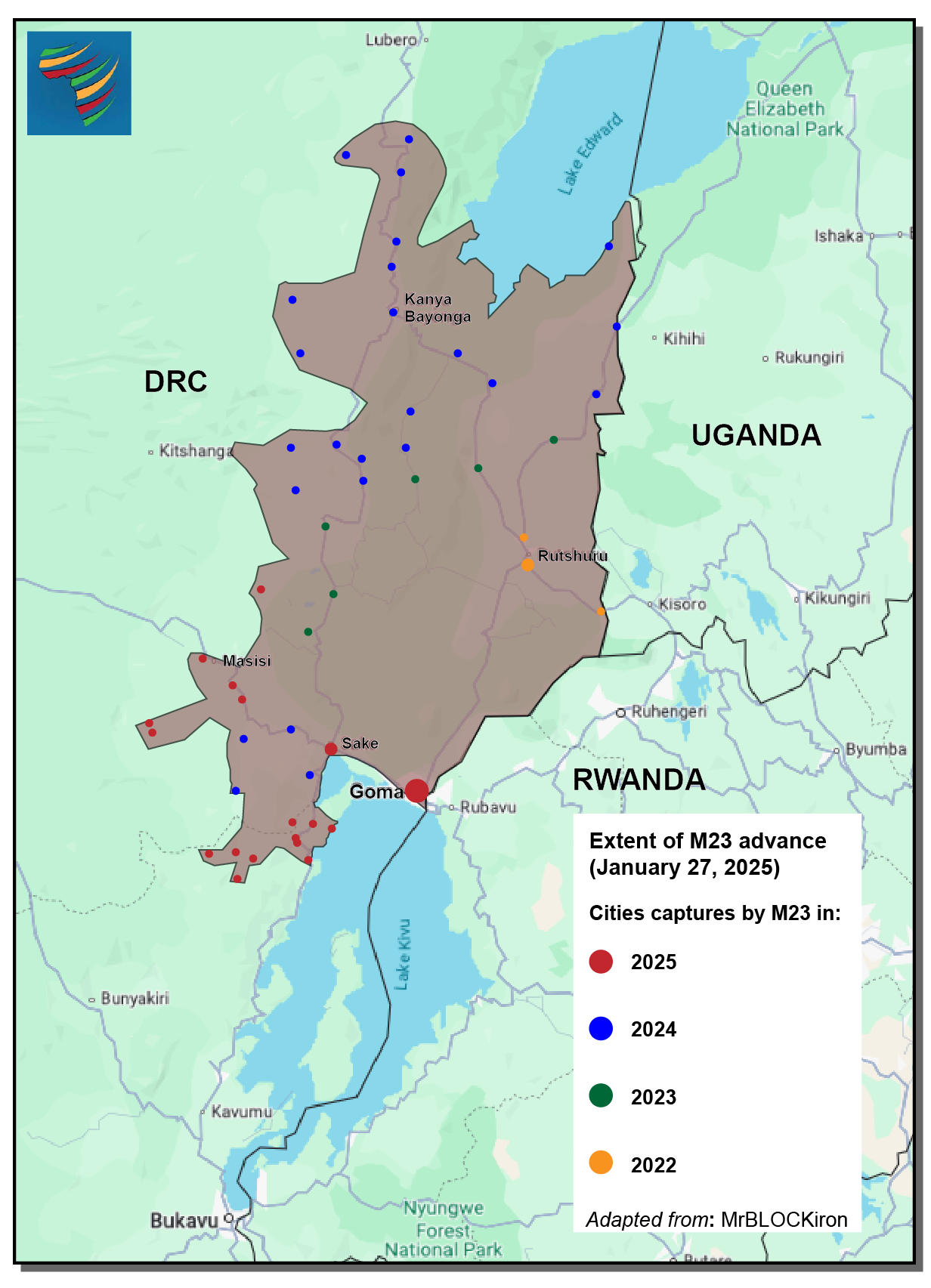

The well-planned and executed seizure of Goma, the capital of the strategic and mineral-rich North Kivu Province in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), continues a widening offensive by M23 since 2022 to seize control of territory in the eastern DRC. This has been accompanied by efforts to establish a parallel civilian administration in areas M23 controls as well as expanded mineral extraction. This suggests that the rebel group and their regional backers have longer term objectives in holding and potentially expanding their territorial control.

The attacks have set off a major humanitarian crisis with displaced people fleeing farther south in the already unstable South Kivu, or across the Rwanda border. According to UN estimates, at least 2,900 people were killed in M23’s seizure of Goma and over 500,000 people have been displaced since January and hospitals are overwhelmed with casualties, many of them civilians. Shops and businesses are being ransacked. Heavy ordnance is landing in civilian areas. At least 17 peacekeepers have been killed including those from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) who are serving in the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO).

Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi is under enormous pressure to respond to the aggression popularly believed to be driven by Rwanda and Uganda. Hundreds of angry protesters in Kinshasa are demanding the government take immediate and decisive action to reclaim the lost territory. Some have set off fires in front of Western embassies out of frustration over the international community’s failure to stop the violence. Others are calling for weapons so they can join the fight in the east.

Who is the M23?

A member of the M23 rebel group monitors access to the border post crossing into Rwanda in Goma on January 29, 2025. (Photo by AFP)

The March 23 Movement was founded in 2012 by a group of former soldiers from the now defunct Congrès national pour la défense du peuple (CNDP), which had broken away from the national army in 2009 following the collapse of a peace treaty signed on March 23 of that year. The peace treaty provided for their integration into the regular military and measures to address the nationality of the Congolese of Rwandan origin, known as Banyarwanda, commonly called “Banyamulenge.”

The former CNDP members regrouped to form M23, claiming to defend the Banyamulenge and combat the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR)—the mostly Hutu remnants of those implicated in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, principally the Interahamwe and ex-Rwandan Armed Forces.

M23 also has roots in the rebel movements sponsored by Rwanda and Uganda during the First Congo War (1996-1997) against Mobutu Sese Seko, and the Second Congo War against Laurent Kabila (1998-2003). Rwanda’s campaigns in the DRC recruited heavily from the Banyamulenge, tapping grievances around nationality and mobilizing kinship ties.

Meanwhile, a third of Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Army and Movement (NRM/NRA) during Uganda’s civil war (1980-1986) was composed of Rwandan immigrants and refugees, as well as Ugandan Banyarwanda. They rose to the top of Uganda’s security apparatus and would later play a central role in the formation of the largely Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Army that fought against the Hutu-led forces perpetuating genocide in Rwanda in 1994. Its leadership would go on to form the basis of Rwanda’s present government.

This historical backdrop explains some of the motivations and recruitment patterns of the Rwandan-backed groups that comprise the M23. They have used messages of self-preservation and safety against persecution to appeal to Banyamulenge communities. Since its resurgence in 2022, it has sought to appeal to other communities and set its sights on national goals like overthrowing the Congolese government. In 2024, M23 merged with 17 political parties and several armed groups to form the Alliance Fleuve Congo (AFC), which is led by Corneille Nangaa, who hails from western DRC. Nangaa served as president of the Independent National Electoral Commission from 2015 to 2021.

Calls for an immediate ceasefire and the pullout of Rwandan troops have come from the UN, European Union, and the United States. Kenyan President William Ruto and his Angolan counterpart, João Lourenço, both of whom have been mediating a multi-track process between Rwanda and the DRC known respectively as the Nairobi and Luanda Processes, called for a return to negotiations without preconditions.

What Happens in Congo Doesn’t Stay in Congo

The fall of Goma could start another extended period of instability for large parts of the country. The Congo wars of the 1990s and 2000s also started in eastern DRC, with key epicenters in Kisangani, Bunia, Bukavu, and Goma. Eventually seven African militaries were engaged. Concerns that Rwanda, with roughly 10 percent of the population size as the DRC, would gain disproportionate influence over one of the largest countries in Africa with nine neighbors, underpins the regional anxiety. The regionalization of the conflict, in turn, complicates efforts to find solutions to what are essentially political and social problems.

The fall of Goma is reminiscent of a previous seizure of the strategic city by M23, back in 2012. This time, however, is much different.

The fall of Goma is reminiscent of a previous seizure of the strategic city by M23, back in 2012. This time, however, is much different. The group appears to be larger, better trained, organized, and armed. Since its resurgence in 2022, M23 has carried out a series of lighting offensives, capturing large parts of North and South Kivu. The weaponry it used includes surface to air missiles, combat drones, and heavy artillery—lending credence to the finding that they received significant state backing. “Their uniforms, their equipment—they are not dressed like a ragtag army. I was a guerrilla fighter myself, so I know what guerrilla fighters look like,” notes South African retired army general, Maomela Moreti Motau. “They are clearly supported by a powerful force.”

Back in 2012, M23 withdrew in the face of massive African and international pressure. This concerted political, diplomatic, and military leverage changed the calculus of M23 and that of Rwanda. The diplomatic environment this time around also appears to be different. Major international partners are distracted and there is a lack of coordination among them and regional countries. The military dynamics on the ground have also changed. “The main actors involved do not seem to be deterred by admonitions by major global powers. What we are seeing now is different from before,” notes a retired AU diplomat.

Eastern DRC residents flee as the M23 rebel group seizes further territory in the east of the country on January 26, 2025. (Photo: AFP/Jospin Mwisha)

Since 2012, Rwanda has positioned itself as a key regional security provider internationally and regionally as an apparent preemptive measure to mitigate the isolation it faced previously. For example, it has troops in Mozambique to fight an Islamist insurgency. This means southern Africa is unlikely to speak with one voice on Rwanda’s role in the DRC. The East African Community (EAC) had deployed forces to the eastern DRC in 2022 to help stabilize the region in the face of rising M23 activity. However, they were asked to depart within a year by Tshisekedi. The bloc, currently chaired by Kenyan President William Ruto, will therefore need to be mobilized to mount a diplomatic response.

The region may be witnessing the start of a campaign aimed at achieving a larger set of military objectives and, potentially building new alliances.

The ever-shifting regional alignments among Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, and the DRC are another complicating factor. Rwanda has accused the DRC and Burundi, which has as many as 10,000 troops and government militia known as the Imbonerakure in the east, of working with the FDLR and other groups like the Wazalendo militia. There are widespread fears among many on the ground in Bukavu in South Kivu—where Burundian soldiers are located—that violence will erupt at any time as more Congo troops retreat there by boat from Goma.

Bukavu is already the epicenter of clashes between Burundian rebel groups and the Burundian military. The Ruzizi Plain, which faces Burundi’s commercial capital, Bujumbura, is also a focus of these tensions. The potential that the escalation of fighting in the Kivus triggers a wider regional conflict, therefore, is high.

With the M23 practically controlling all of North Kivu and pressing deeper into South Kivu, the region may be witnessing the start of a campaign aimed at achieving a larger set of military objectives and potentially building new alliances.

The assault on Goma has also occurred in a changed security context. Former staunch allies turned bitter rivals and now diplomatic partners, Uganda and Rwanda do not seem to be as opposed to each other as they were when M23 seized the city back in 2012. In 2014, about 1,000 M23 fighters vanished from a military base in western Uganda where they were cantoned following their breakup in 2013 (a smaller force was disarmed and cantoned in Rwanda). Then in 2021, Uganda, through an agreement with the DRC, began constructing new roads, bridges, and other infrastructure in North Kivu, from Bunagana to Rutshuru, Goma, and down to the Rwandan border.

Uganda and Rwanda have a long history of military intervention in the DRC, first as allies during the First Congo War under a joint military command against the longtime Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko. They were then rivals when they fought on Congolese soil in support of rival movements seeking to overthrow the Congolese government of Laruent Kabila during the Second Congo War. It is hard to predict how the two neighbors, whose top military staff had a flurry of exchanges in recent months, will relate to each other in the latest flare-up.

An underlying economic factor to all of the DRC’s multiple and complex conflicts is the Congo’s vast mineral wealth, particularly in the east. The region is a major source of coltan, cobalt, tantalum and lithium, which are crucial components for modern communication devices. Rwanda, in particular, is alleged to be facilitating the illicit mining and trafficking of these minerals. The market value for these minerals is likely to exceed over $1 billion. This represents another driver of the conflict that will need to be addressed if a comprehensive peace is to be achieved.

Members of the M23 rebel group on patrol in Goma, DRC on January 29, 2025. (Photo: AFP)

Averting a Regional War

There are many unknowns in the rapidly changing crisis in the eastern DRC. One factor remains constant, however. The underlying political, social, and economic drivers that have fueled the instability do not lend themselves to a military solution. There is already a framework in place to address the DRC’s internal conflicts—including the issue of citizenship and nationality—and the external dimensions of the crisis involving neighboring countries. The Sun City Accords, concluded as part of the Inter-Congolese Dialogue (ICD) between 2001 and 2003, created a template for a comprehensive peace that addressed the root causes of Congo’s complex political and social conflicts. The parallel, Lusaka Peace Accord, addressed the external elements of the crisis.

The Ituri Pacification Committee, which flowed from both processes, localized the peace building framework in the volatile region of Ituri, paving the way for the establishment of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR)—a mechanism for UN engagement in support of the commitment of each of the parties.

The immediate challenge is to create the political will for de-escalation so that these dialogues can regain traction.

Some of this institutional memory and experience has been revitalized in two concurrent processes designed to bring Rwanda and the DRC into a political dialogue: the Luanda process, chaired by Angolan President João Lourenço, and the Nairobi process, supervised by Kenyan President William Ruto.

The immediate challenge is to create the political will for de-escalation so that these dialogues can regain traction and the frameworks for addressing the underlying drivers revitalized.

Additional Resources

- International Crisis Group, “Fall of DRC’s Goma: Urgent Action Needed to Avert a Regional War,” Statement, January 28, 2025.

- Paul Nantulya, “Understanding the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Push for MONUSCO’s Departure,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 20, 2024.

- Peter Fabricius, “Once More into the Breach: SADC Troops in DRC,” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, February 9, 2024.

- Coralie Pierret, “The ‘Wazalendo’: Patriots at War in Eastern DRC,” Le Monde, December 19, 2023.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Rwanda and the DRC at Risk of War as New M23 Rebellion Emerges: An Explainer,” Spotlight, June 29, 2022.