Français | Português | العربية

A medical officer in Somalia prepares to administer a dose of COVID-19 vaccine. (Photo: AMISOM)

The rollout of COVID-19 vaccines was supposed to be a light at the end of the pandemic tunnel. Yet, just as the supply of vaccines has been increasing in Africa, so too has misinformation about their safety and efficacy.

Fears about the vaccines range from simple lack of information to far-fetched conspiracy theories. Concerns on the continent heightened after several European countries stopped using Oxford University’s AstraZeneca vaccine following reports of blood-clotting among a small sample of recipients. While these countries have resumed their use of this vaccine, doubts in the minds of many Africans linger.

Comments by prominent African leaders have created further confusion and mistrust. Madagascar’s President Andry Rajoelina dismissed vaccines altogether, preferring instead to promote an untested herbal remedy, as a cure for the disease.

A survey by the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that vaccine hesitancy is compounding the COVID threat. More than half of respondents in 15 high-risk countries said that the seriousness of COVID-19 is exaggerated. In Uganda, only 350,000 people turned up to get the jab, even though 960,000 vaccine doses became available in February. According to the WHO, 22 African countries have used less than a quarter of their supplied vaccines. In May 2021, Malawi incinerated 20,000 expired vaccines, becoming the first African country to do so. South Sudan plans to discard 59,000 shots, while the Democratic Republic of the Congo says it cannot use most of the 1.7 million doses it received earlier this year.

So, what are some of the key myths circulating on the continent?

Myth: There is no COVID.

In fact, COVID-19 has been confirmed in every country in the world. The Africa CDC warns that COVID is very real. There have been 4.7 million positive cases and over 127,000 known deaths from COVID-19 on the continent. Due to limited testing capabilities, the actual figures are likely several times larger.

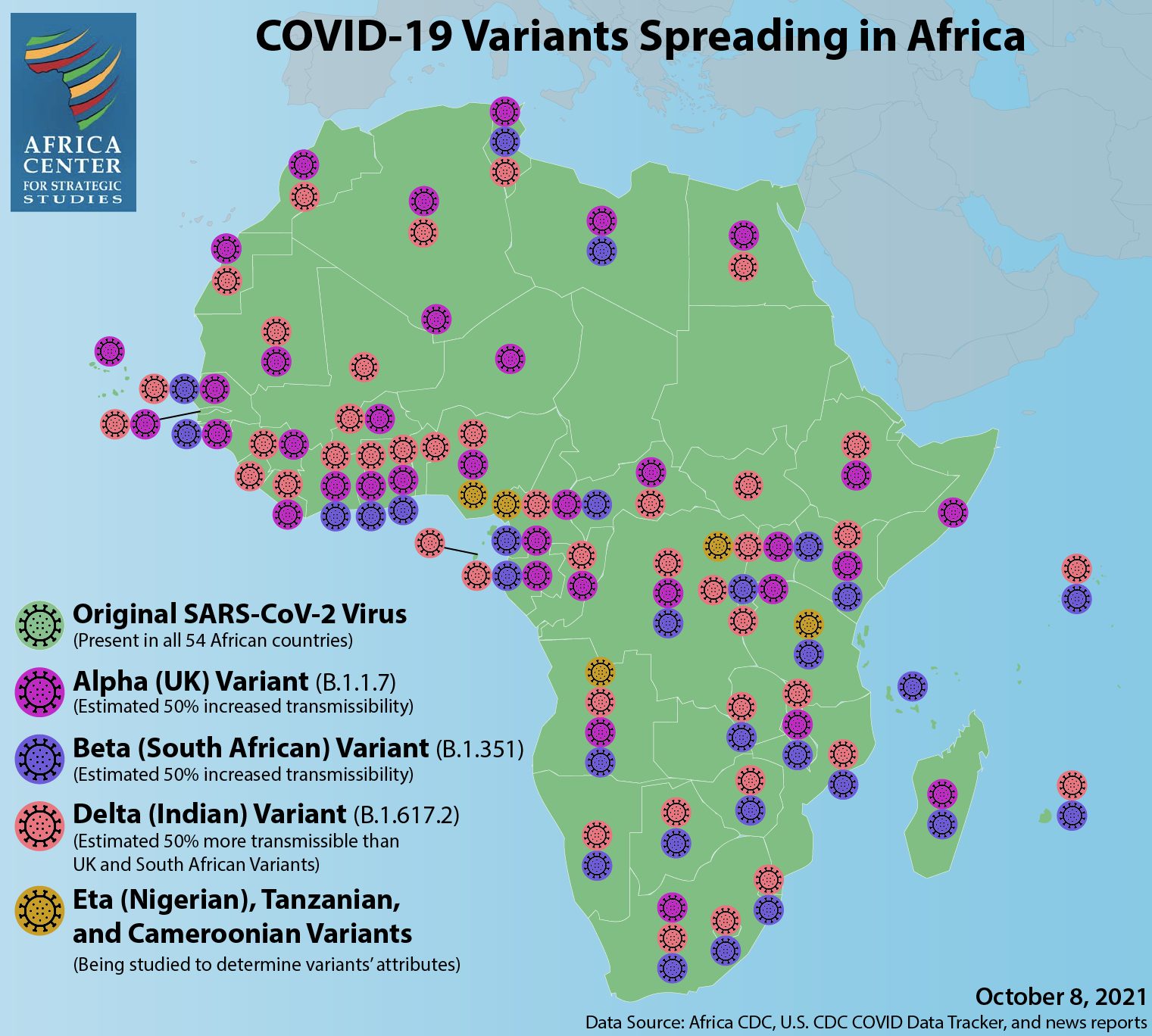

Meanwhile, the virus is constantly evolving. In some cases, the new variants are more transmissible and deadly than the original. A variant originating in India was first detected in Africa in Uganda on April 29, 2021. Within a matter of weeks, the Indian variant had spread to at least eight other African countries. Currently, there are a half dozen active COVID variants on the continent. Low vaccination rates on the continent provide the virus an opportunity to produce mutations and spin out of control—across Africa and potentially around the world.

Myth: COVID was concocted by my government to hold on to power.

COVID skepticism was exacerbated in certain countries when governments politicized the virus. Uganda is one example. After taking early, proactive measures, the ruling National Resistance Movement party was accused of flouting health guidelines as it fought a bitter election campaign against the rival National Unity Platform. The public mood shifted from cooperation to defiance as security forces were accused of enforcing COVID-19 guidelines selectively against opponents.

This was made worse when the health minister, without a mask, was seen rallying massive NRM crowds against her own directives. Currently, few Ugandans observe health guidelines to prevent the spread of COVID-19. This is reflected in the low vaccination rates. Others claim that Uganda’s low infection rates “prove” that the government is exaggerating the risk of COVID-19 for political gain.

Uganda is not alone in facing this challenge: a similar disconnect between governments and citizens has fueled vaccine hesitancy in other countries, particularly those that have recently undergone controversial elections, such as Burundi, Chad, Tanzania, Benin, Djibouti, and the Republic of the Congo.

Myth: Vaccines are dangerous.

“Anti-vaccine activists … have used social media to amplify unfounded fears of the COVID vaccines.”

One myth holds that live viruses are injected into the body and that individuals can die after vaccination. Another says that the vaccines cause infertility or serious side effects that are worse than contracting the virus. Other conspiracy theories hype that that the vaccines are in fact poisons that alter the DNA to reduce Africa’s population. They also claim that vaccines are a cover to implant traceable microchips, and that Microsoft founder Bill Gates and the U.S. government are behind it.

Many myths around vaccine safety can be traced back to anti-vaccine activists, who have used social media to amplify unfounded fears of the COVID vaccines.

The reality is that WHO has approved for emergency use listing all vaccines currently available in Africa through the WHO’s COVID-19 Global Access (COVAX) facility—AstraZeneca, Moderna, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and Sinopharm. The listing is designed to make vaccines available as rapidly as possible to address an emergency, while adhering to stringent criteria of safety, efficacy, and quality.

Currently, there are three types of COVID vaccines:

- Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines like Pfizer and Moderna are not a form of the virus. They use genetically engineered mRNA to “teach” cells to produce harmless pieces of the spike protein (S protein) found on the surface of the coronavirus. The body recognizes them as intruders and creates antibodies to extinguish them.

- Vector vaccines like Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca insert genetic material from the virus into a weakened live virus that instructs the body to make copies of the S protein. This triggers the immune system to produce antibodies and defensive white blood cells to fight the virus if you get infected.

- Protein sub-unit vaccines like Novavax use parts of the COVID-19 virus to stimulate the immune system. The harmless S protein “tricks” the body to produce antibodies that fight off infection if you fall sick.

“Getting young people vaccinated is a critical step in protecting their communities and helping overcome the pandemic.”

Side effects indicate that antibodies have been produced and are fighting off the harmless material introduced into the body. In short, it is a sign that the immune system has been primed to protect someone if they are infected. Reported side effects have been mostly mild to moderate and short-lasting. More serious side effects are possible but extremely rare, and the chances of death are minuscule. This compares to a mortality rate of 2.7 percent for Africans who have contracted the virus. There is no evidence that any of the vaccines cause infertility or terminal illnesses.

Myth: COVID does not pose a serious threat to Africans.

This theory swirled in African social media circles during the initial outbreak. It claims that “COVID-19 only kills White people,” and people of color have “genetic immunity.” The myth has persisted, fueled in part by the lower infection and death rates in Africa compared to Europe and North America.

In actuality, studies have shown that African countries were able to slow the virus through early action and high public support for social distancing in the initial stages of the pandemic. This response was complemented by a prevention-focused public health approach to infectious diseases, a young demographic and few old age homes, strong community-level health worker networks, and experience with pandemics. Some studies explored possible “genetic hypotheses” but these were emphatically rejected by leading African immunologists.

A man in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, receives a COVID-19 vaccine. (Photo: UN)

They have argued that had African ancestry been a source of genetic or immunological resiliency, then people of African origin in North America and Europe should have been more resistant to the virus, which is not the case. The science says that the spread of COVID-19 can be mitigated by practicing responsible public health behaviors, such as wearing masks, maintaining social distancing, avoiding large congregations of people, and frequent handwashing. These preventative measures can keep people healthy and out of intensive care, until vaccinations become available.

Myth: COVID does not affect young people.

In fact, unlike the original virus, the B.1.1.7 (U.K.) variant and B.1.617.2 (Indian) variants that have spread rapidly across Africa are infecting young people at a much higher rate. The new variants in India are also spreading rapidly among young populations. Moreover, there is some evidence that these newer variants, rather than just exploiting compromised immune systems, are causing some young healthy immune systems to overreact, resulting in severe inflammation and other serious symptoms. Young people are also susceptible to long-term COVID-19 effects—so-called “long-haulers,” who experience chronic fatigue, chest pain, shortness of breath, and brain fog months after their infection. Young adults can also be asymptomatic transmitters of the virus, posing a public health risk to the wider community. Getting young people vaccinated, therefore, is a critical step in protecting their communities and helping overcome the pandemic.

Myth: China, Russia, and the United States are competing against one another while trying to kill Africans and shrink our population for their own interests.

According to the Africa CDC, half of Africans believe that COVID was planned by foreign powers. “It was invented as a fake disease by China and America to ruin our economy because they saw how close we are getting to them,” says one Tanzanian citizen. Another common myth claims that COVID-19 is a bioweapon created by major powers to promote their own interests.

“The United States, China, and Russia have used the identical vaccines available in Africa to safely vaccinate tens of millions of their own people.”

This myth builds on some of the vaccine narratives that have been promoted. China has mocked the U.S. COVID response and portrayed itself as a more “competent” emerging world power.

In 2020, public health officials in the United States expressed skepticism over Chinese and Russian claims to have developed vaccines prior to testing. China, in turn, has used its extensive media apparatus in Africa to amplify numerous COVID narratives, including that the Pfizer and Moderna shots were risky. Russian disinformation campaigns have also played up the seriousness of vaccine side effects.

In fact, the United States, China, and Russia have used the identical vaccines available in Africa—AstraZeneca, Moderna, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Sinopharm, and Sputnik V—to safely vaccinate hundreds of millions of their own people. These vaccines (apart from Russia’s Sputnik V) have all been approved by the WHO under its emergency use listing and comprise the same brands available through the COVAX facility. In February 2021, the authoritative Lancet medical journal found that Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine appeared to be safe and effective.

Myth: Traditional tonics will cure me. I have no need for vaccines.

African communities have a long-standing culture of self-care, with people only going to hospital when seriously ill. Uncomplicated ailments like colds, fevers, and chest congestion are treated using traditional remedies and local knowledge. As shown in numerous surveys, African communities largely view COVID-19 as a disease that attacks the respiratory tract and causes severe malaria-like symptoms, such as chills and high fevers. However, these are still seen as manageable through traditional treatments given that standard treatment protocols were unavailable during the initial outbreak. Countries like Madagascar actively encouraged citizens to drink various tonics, though it subsequently reversed course and is now pursuing a widespread vaccination campaign. Tanzania encouraged prayer and herbal drinks, commonly known in East Africa as “dawa,” before embracing a science-based approach after President Samia Suluhu Hassan assumed office in March 2021.

“Scientific data shows that COVID is not ‘another type of flu’ that can be cured using home remedies.”

In fact, scientific data shows that COVID is not “another type of flu” that can be cured using home remedies. Some highly transmissible variants like the Indian, Kenyan, and Tanzanian ones do not even present flu symptoms and attack the lungs directly. In September 2020, the WHO and African CDC agreed to test the efficacy of African herbal remedies for the coronavirus. Until these are approved for fast-track manufacturing, they are not scientifically proven cures for COVID-19.

Guidelines and Getting Vaccinated

Myths about the coronavirus vaccine are causing African communities to delay getting vaccinated at a time when new, more transmissible, and more lethal variants are circulating. African public health officials, political and civic leaders, and celebrities all have important roles to play in building vaccine confidence on the continent. These public education efforts must be coupled with comprehensive vaccination plans if Africa is to become protected from COVID-19 and reduce the potential for the emergence of new variants that may set back the global effort to end this pandemic.

Vaccine hesitancy has a long history in Africa. Still, Africa has achieved remarkable success with some vaccine campaigns, including a 99-percent vaccination rate against polio. This came after decades of relentless efforts by governments, community health workers, NGOs, and citizens. Just in the past year, vaccines have helped contain Ebola outbreaks in West and Central Africa. Public trust played a major role in these campaigns. Restoring trust in the COVID vaccine campaign will require pushing back against vaccine myths and creating an environment of people-centered, transparent, and inclusive vaccine outreach.

Additional Resources

- WHO Coronavirus Mythbusters

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus Dashboard

- Aminatou Seydou, “Who Wants COVID-19 Vaccination? In 5 West African Countries, Hesitancy Is High, Trust Low,” Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 432, March 9, 2021.

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, “COVID 19 Vaccine Perceptions: A 15-Country Study,” Report, February 2021.

- Munyaradzi Makoni, “Africa Eradicates Wild Polio,” The Lancet Microbe, October 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Five Myths about Coronavirus in Africa,” Spotlight, March 27, 2020.

More on: Disinformation COVID-19 Health & Security