The 42nd Chinese naval escort fleet arrives at the Port of Richards Bay, South Africa. (Photo: AFP)

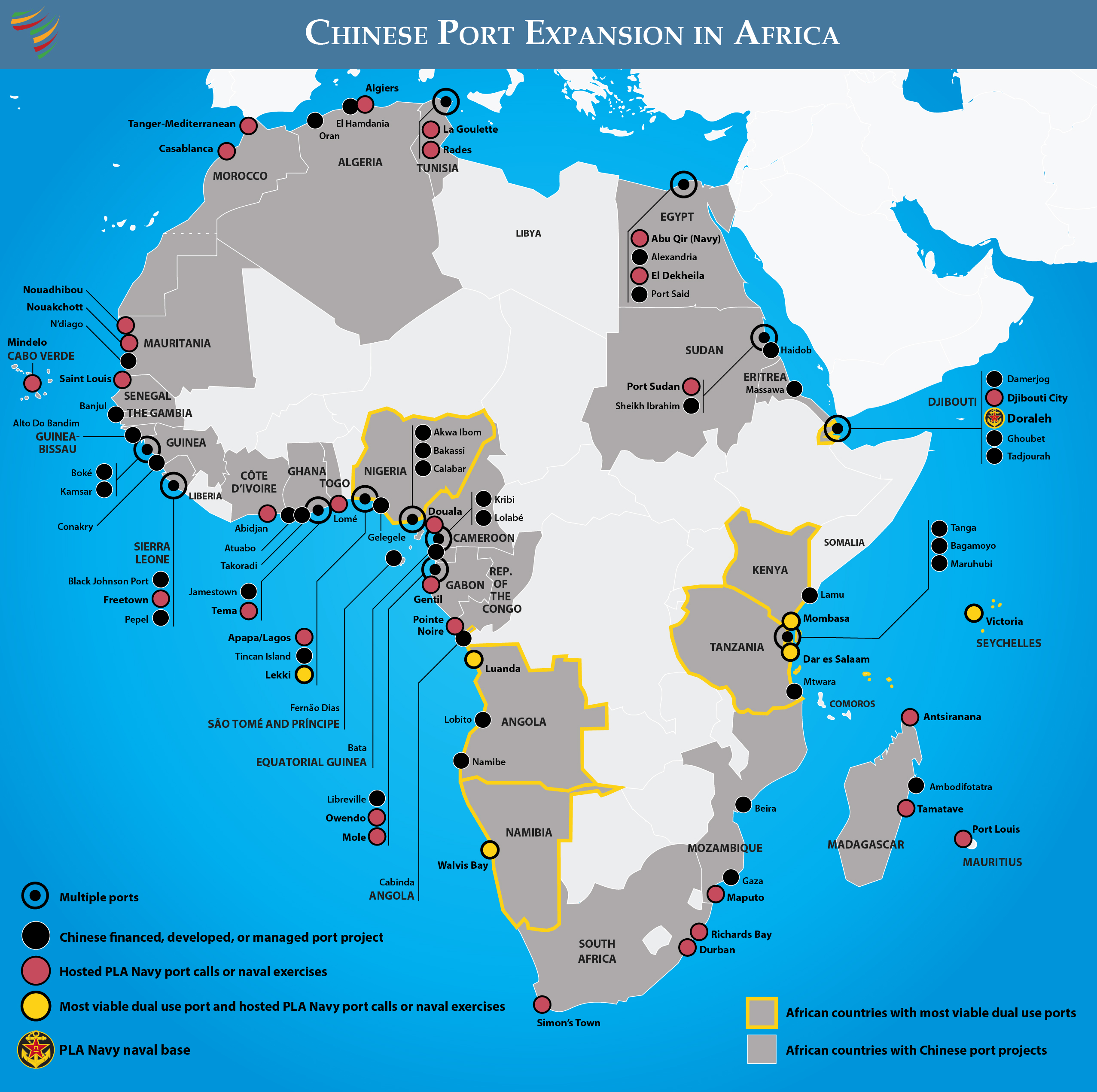

Chinese state-owned firms are active stakeholders in an estimated 78 ports across 32 African countries as builders, financiers, or operators. Chinese port developments are concentrated in West Africa, with 35 compared to 17 in East Africa, 15 in Southern Africa, and 11 in North Africa.

With a total of 231 commercial ports in Africa, Chinese firms are present in over a third of Africa’s maritime trade hubs. This is a significantly greater presence than anywhere else in the world. By comparison, Latin America and the Caribbean host 10 Chinese-built or operated ports, while Asian countries host 24.

Chinese firms are present in over a third of Africa’s maritime trade hubs—a greater presence than anywhere else in the world.

In some sites, Chinese firms dominate the entire port development enterprise from finance to construction, operations, and share ownership. Large conglomerates like China Communications Construction Corporation (CCCC) will win work as prime contractors and hand out sub-contracts to subsidiaries like the China Harbor Engineering Company (CHEC). This is the case in one of West Africa’s busiest ports, Nigeria’s Lekki Deep Sea Port. CHEC did the construction and engineering, secured loan financing from the China Development Bank (CDB), and took a 54-percent financial stake in the port which it operates on a 16-year lease.

China gains as much as $13 in trade revenues for every $1 invested in ports. A firm holding an operating lease or concession agreement reaps not only the financial benefits of all trade passing through that port but can also control access. The operator determines the allocation of piers, accepts or denies port calls, and can offer preferential rates and services for its nation’s vessels and cargo. Control over port operations by an external actor, accordingly, raises obvious sovereignty and security concerns. This is why some countries forbid foreign port operators on national security grounds.

Chinese firms hold operating concessions in 10 African ports. Despite the risks over loss of control, the trend on the continent is toward privatizing port operations for improved efficiency. Delays and poor management of African ports are estimated to raise handling costs by 50 percent over global rates.

Chinese PLA personnel at the opening ceremony of China’s military base in Djibouti. (Photo: AFP)

Another concern of China’s expansive port development in Africa is the possibility of repurposing commercial ports for military activities. China’s development of Djibouti’s Doraleh Port, long marketed as a purely commercial venture, was extended to accommodate a naval facility in 2017. It, thus, became China’s first known overseas military base 2 months after the main port was opened. There is widespread speculation that China could replicate this model for future basing arrangements elsewhere on the continent.

This raises concerns about China’s broader geostrategic aims with its port development and stokes Africans’ widely held aversion to being pulled into geostrategic rivalries. There is also a growing wariness against hosting more foreign bases in Africa. This underscores the mounting African and international interest in scrutinizing China’s port development—and dual-use military basing—scenarios.

The Logic behind China’s Ports Strategy

China’s strategic priorities involving foreign ports are laid out in China’s Five-Year Plans. The current Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) talks about a “connectivity framework of six corridors, six routes, and multiple countries and ports” to advance Belt and Road construction. Notably, three of these six corridors run through Africa, landing in East Africa (Kenya and Tanzania), Egypt and the Suez region, and Tunisia. This reinforces the central role that the continent plays in China’s global ambitions. The Plan articulates a vision to build China into “a strong maritime country”—part of its larger rejuvenation as a Great Power.

An unofficial term that often appears in Chinese strategic analyses is “overseas strategic strongpoint” (haiwai zhanlue zhidian; 海外战略支点), sometimes called “maritime strategic strongpoint.” This refers to foreign ports with special strategic and economic value that host terminals and commercial zones operated by Chinese firms. Ports in which Chinese firms have equity arrangements provide similar leverage over port operations. Notably, under China’s technical standards for “military civil fusion” (junmin ronghe; 军民融合), many Chinese state owned commercial shipping and civilian air cargo capabilities meet military specifications for defense logistics purposes.

Dependence on Chinese export infrastructure makes African countries amenable to supporting Chinese global interests.

China’s focus on African port development was facilitated by the “Go Out” strategy (zouchuqu zhanlue; 走出去战略), a government initiative to provide state backing—including massive subsidies—for state-owned firms to capture new markets, especially in the developing world. One Belt One Road (known internationally as the Belt and Road Initiative)—China’s global effort to connect new trade corridors to its economy—is a product of Go Out, sometimes referred to as “Go Global.”

Africa has been a central feature of the Go Out strategy, where port infrastructure was a major impediment to expanding Africa-China trade. Heavy Chinese government subsidies and political backing encouraged Chinese shippers and port builders to seek footholds on the continent. They benefitted from robust government and party-to-party ties that China cultivated over time. All told, Africa became highly attractive to China’s state-owned enterprises, despite the many risks of doing business on the continent.

China’s port development strategy has also linked up Africa’s 16 landlocked countries via Chinese-built inland transport infrastructure, facilitating getting goods and resources to market and vice versa. These have come to be called One Belt One Road connector projects.

Chinese firms also capitalized on opportunities to export their technologies and expertise. They positioned themselves as dominant players in building export infrastructure that African countries came to increasingly depend on to conduct foreign trade. This has created political windfalls for China. As a senior African Union diplomat puts it, “African dependence on Chinese export infrastructure makes African countries amenable to supporting Chinese global interests and less inclined to taking sides against it or supporting sanctions.”

Military Engagement

China’s growing footprint in African ports also advances Chinese military objectives. Some of the 78 port sites that Chinese firms are involved in can berth PLA Navy vessels based on their specifications while others can dock PLA Navy vessels on port calls. Illustratively, the PLA Navy has called on the following African ports in recent years:

- Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire)

- Gentil (Gabon)

- Casablanca (Morocco)

- Tamatave (Madagascar)

- Maputo (Mozambique)

- Tincan (Nigeria)

- Pointe-Noire (Republic of Congo)

- Victoria (Seychelles)

- Durban (South Africa)

- Simon’s Town (South Africa)

Some of these ports have also been staging grounds for PLA military exercises. These include the ports of Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), Lagos (Nigeria), Durban (South Africa), and Doraleh (Djibouti). The latter involved exercises with landlocked Ethiopia. Chinese troops have also made use of naval and land facilities for some of their drills, including Tanzania’s Kigamboni Naval Base, Mapinga Comprehensive Military Training Center, and Ngerengere Air Force Base—all built by Chinese firms. The Awash Arba War Technical School has served a similar purpose in Ethiopia, as have bases in other countries.

In total, the PLA has conducted 55 port calls and 19 bilateral and multilateral military exercises in Africa since 2000.

Beyond direct military engagements, Chinese firms handle military logistics in many African ports. For example, Chinese state-owned enterprise Hutchison Ports has a 38-year concession from the Egyptian Navy to operate a terminal at the Abu Qir Naval Base.

There has been much speculation and debate over which of these ports might be the location for additional Chinese military bases besides Doraleh in Djibouti. While the available data and decision criteria are limited, certain measures provide some indicators.

Beyond direct military engagements, Chinese firms handle military logistics in many African ports.

As seen in the development of Doraleh (in which Chinese firms held 23 percent of the stakes), size of Chinese shareholding of a port is an inadequate factor on its own. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that Chinese firms hold 50 percent stakes in three West Africa ports: Kribi, Cameroon (66 percent), Lekki, Nigeria (52 percent), and Lomé, Togo (50 percent).

Previous PLA engagement is another consideration. Of the 78 African ports in which Chinese firms are known to be involved, 36 have hosted PLA port calls or military exercises. This demonstrates that they have the design features to support Chinese naval flotillas making them potential candidates for future PLA navy bases.

Not all of these have the proven physical specifications to berth PLA vessels, however. This considers factors such as number of berths, berth length and size, and capabilities for fueling, replenishment, and other logistics.

Beyond the physical specifications are political considerations such as strategic location, the strength of a government’s party-to-party ties with China, its ranking within China’s system of partnership prioritization, membership in China’s One Belt One Road network, and levels of Chinese foreign direct investment and high-value Chinese assets. Commonly ignored but no less important is the strength and capacity of public opinion to shape local decisions.

Considering just the design features, seven ports stand out for the likelihood of being employed for future Chinese military use:

- Luanda (Angola)

- Doraleh (Djibouti)

- Mombasa (Kenya)

- Walvis Bay (Namibia)

- Lekki (Nigeria)

- Victoria (Seychelles)

- Dar es Salaam (Tanzania)

Notably, these span both Atlantic and West Indian Ocean locations despite the preponderance of Chinese port development activity in West Africa.

Other countries, such as Equatorial Guinea, have been widely speculated as likely targets for future PLA Navy basing. However, they seem less suitable when taking the full gamut of criteria into consideration. Nevertheless, debate on the continent persists given the strong African aversion to foreign military intervention. The conjecture was heightened when it emerged that China might have explored basing opportunities in Namibia’s Walvis Bay. This possibility first appeared in the Namibian press in 2015, triggering a denial from the Chinese Embassy. Given that similar denials were made when stories began circulating about a potential Chinese base in Djibouti prior to the development of Doraleh, those disavowals have failed to tamp down on speculation of similar outcomes in other locations.

Advancing African Interests

Former PLA Navy Commander Wu Shengli noted that, “overseas strategic strongpoint” ports were always envisioned as platforms for building an integrated Chinese presence. In other words, China has been highly strategic in its development and management of African ports so that this advances China’s interests as part of Beijing’s geostrategic ambitions. Looking into the future, it can be expected that China will seek to increase its role in building African ports to expand its ownership and operational control toward Chinese commercial, economic, and military ends.

Rarely do discussions publicly address the sovereignty or security dimensions of these port developments.

African debates on Chinese-built or operated port infrastructure tend to focus on the impact these ports can have on advancing Africa’s economic output by improving efficiencies, reducing the costs of trade, and expanding access to markets. While some concerns are raised as to the implications these projects have on Africa’s increased debt burden incurred vis-à-vis China, rarely do these discussions publicly address the sovereignty or security dimensions of these port developments, or the role that commercial platforms could play in potential Chinese basing scenarios.

The heightened pace of China’s military drills and naval port calls in Africa in recent years has generated increased attention to these issues in the African media, think tanks, and policy discussions. The growing militarization of China’s Africa policy is stoking concerns about the implications of more foreign bases in Africa. Some are concerned that Chinese basing scenarios could inadvertently draw African countries into China’s geopolitical rivalries, undermining the continent’s stated commitment to nonalignment.

Ensuring that Chinese port investments advance African interests will require African governments, national security experts, and civil society leaders to grapple with the policy implications of these choices. Beyond the straightforward desire to expand export infrastructure are tangible issues of maintaining fiscal prudence, safeguarding national sovereignty, avoiding geopolitical alignments, and advancing a country’s strategic interest.

Additional Resources

- Paul Nantulya, “The Growing Militarization of China’s Africa Policy,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 2, 2024.

- Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Chinese Military Diplomacy Database, version 4.98 (Washington, DC: National Defense University, August 2024).

- Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “Tracking China’s Control of Overseas Ports,” Council on Foreign Relations, August 26, 2024.

- Yan Wang and Yinyin Xu, “Direct Impacts and Spatial Spillovers: The Impact of Chinese Infrastructure Projects on Economic Activities in Sub Saharan Africa,” Global China Initiative Working Paper 036, Boston University Global Policy Center, May 2024.

- Alex Vines, Henry Tugendhat, and Arminda van Rij, “Is China Eyeing a Second Military Base in Africa?” Analysis, United States Institute of Peace (USIP), January 30, 2024.

- Paul Nantulya, “Considerations for a Prospective New Chinese Naval Base in Africa,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 12, 2022.

- Isaac Kardon, “China’s Ports in Africa,” in (In)Roads and Outposts: Critical Infrastructure in China’s Africa Strategy, NRB Special Report No. 98, ed. Nadège Rolland, National Bureau of Asian Research, May 3, 2022.

More on: China in Africa Maritime Security