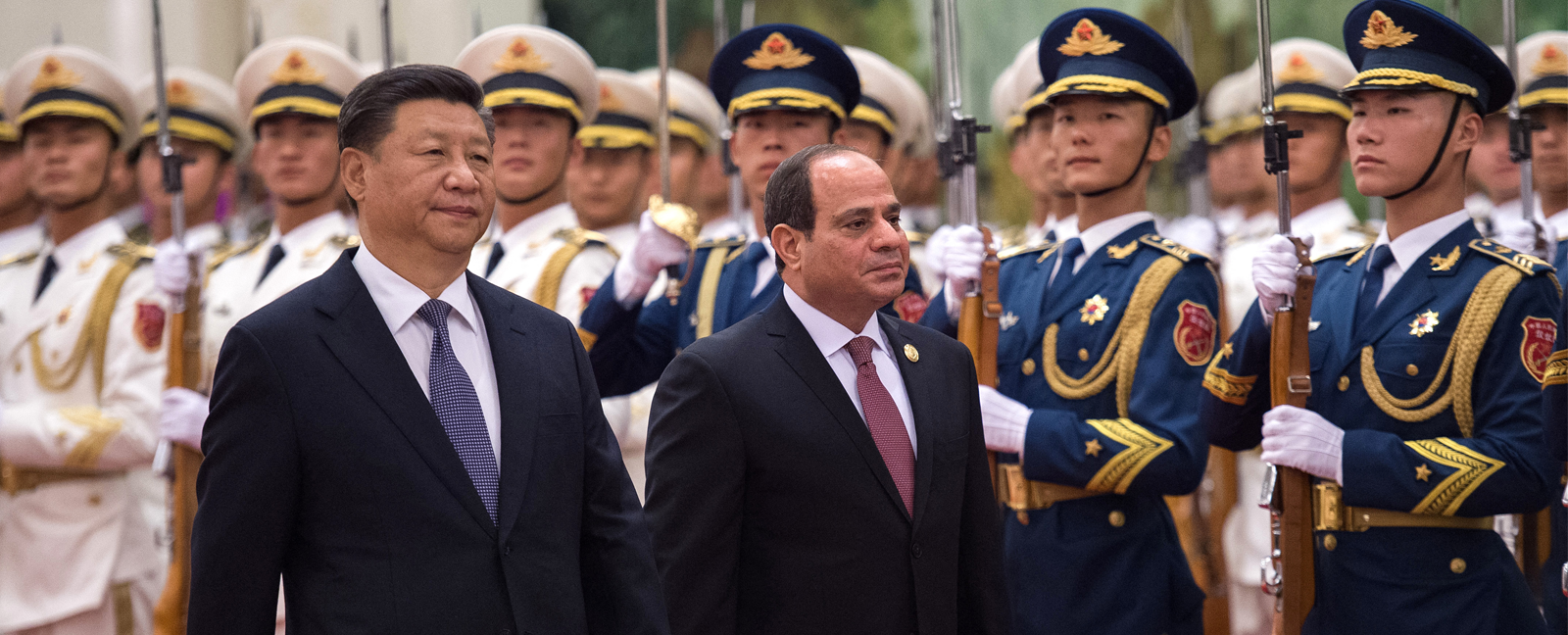

China’s President Xi Jinping and his Egyptian counterpart Abdel Fattah al-Sisi review the Chinese People’s Liberation Army honour guard during a welcome ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in 2018. (Photo: AFP/Nicolas Asfouri)

The Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Beijing Action Plan (2025-2027) is notable for containing more security commitments than any previous FOCAC action plans. This underscores China’s aim to become a major security actor in Africa alongside its economic influence. When FOCAC started in 2000, China held less than 5 percent of African weapons inventories, admitted less than 200 African officers in its military schools, and did not conduct military drills in Africa. Today, China is training roughly 2,000 African officers annually and has become a leading arms supplier on the continent. Roughly 70 percent of African countries now operate Chinese armored vehicles.

China’s joint drills with African forces—of which there have been 20 since 2006—have grown in scale and sophistication in recent years, as illustrated by the August 2024 Tanzania-China-Mozambique land and sea exercises and the joint Chinese and Egyptian air force drills in May 2025. These were respectively the largest Chinese deployments of ground, naval, and air forces in Africa ever.

China has also deployed 47 escort task groups on continuous rotations in the Gulf of Aden and conducted 280 defense exchanges since 2007. The exchange in May 2025, brought 100 African early career officers from 40 countries on a 10-day familiarization tour hosted by the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) National University of Defense Technology.

In the CCP context, national security, party, and state security are interchangeable.

China’s overarching security concept known as the Global Security Initiative is guiding China’s expanded security engagements in Africa. These engagements are integrated with deepening political support for selected ruling parties and the promotion of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) security norms and governance practices. China, thus, aims to gain favor with ruling elites, secure preferential treatment for its companies, and enlist African support for its geopolitical ambitions.

China’s expanding security engagements have not been without problems. Chinese arms have at times fallen into the hands of militants in conflict zones such as Mali, Darfur, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Provided with few oversight regulations, Chinese arms and surveillance equipment have been used by some African governments to harass and suppress political opponents.

Such outcomes from expanding Chinese security engagements are fueling negative sentiments by some segments of African public opinion of China, which is often criticized for entrenching illiberal practices in Africa. It also poses a dilemma over the divergence in African citizen interests from China’s widening security and geostrategic ambitions on the continent.

Security Engagement with Chinese Characteristics

Official Chinese views on security are predicated on the hegemony of the CCP as the sole leader of society and backbone of the state, government, and military. The CCP prioritizes “stability maintenance” (weiwen; 维稳), which holds that regime legitimacy and public consent to CCP rule derive from its ability to impose and maintain social order. In the CCP context, national security (guojia anquan; 国家安全), party, and state security are interchangeable. China’s 2015 National Security Law defines state security as “the relative absence of international or domestic threats to the state’s power to govern.” The state is defined as “persisting in the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.”

These concepts frame China’s overseas security assistance, including Africa, where certain ruling parties exercise power in ways similar to China’s governing party. Some African uniformed services also remain oriented toward regime security instead of citizen protection. This creates an opening for China to advance its governance model and perspective on security while instilling CCP norms and practices.

In fact, African partners of Chinese security engagements typically enjoy close party-to-party exchanges with the CCP. Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe receive more than 90 percent of their arms from China. In 2024, Namibia was the first foreign country to acquire the Shaanxi Y-9E medium military transport aircraft.

The CCP has also built inroads elsewhere. Burundi, Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal each receive over 50 percent of their weaponry from China. Over the same period, these countries had some of the most frequent exchanges with the CCP.

Zimbabwe’s President Emmerson Mnangagwa receives military equipment from China in December 2023. (Photo: Zimbabwe Office of the President and Cabinet)

A Differentiated Security Assistance Strategy

China’s closest ties on the continent are often with the liberation movement parties that have monopolized power since independence. In Tanzania, for example, the military inventory, order of battle, military doctrine, and service culture are heavily inspired by China.

This, at times, builds on a long legacy of engagement. After the failed coup attempt in 1964, the leadership of newly independent Tanzania disbanded the entire military, expelled British and Soviet instructors, and turned to China to build the Tanzania People’s Defence Force from scratch. China remains Tanzania’s principal military partner and a primary source of weaponry, education and training, and residential military advisors. This entails frequent military drills and major weapons systems like amphibious tanks, patrol boats, and fighter jets. Most of Tanzania’s important installations like Ngerengere Air Base, Kigamboni Naval Base, and the Comprehensive Military Training Center, Mapinga, are also Chinese built. So are most of its professional military education institutions like Monduli Military Academy and National Defense College.

China is also expanding military ties with nontraditional partners like Senegal and Kenya, though this process is less straightforward. Under then President Abdoulaye Wade’s “Look East” policy, Senegal officially recognized Beijing in 2005. Senegal then joined FOCAC the following year, opening the door for the admission of Senegalese officers to Chinese staff colleges. In 2009, then Chinese President Hu Jintao visited Senegal and announced a multiyear package of aid and grants, including $49 million in additional funding for military education and training and an assortment of equipment for the police and gendarmerie.

China sequenced its security engagements with direct support for Wade’s priority economic and infrastructure projects, including the $138 million Gouina Hydropower Project. The CCP stepped up its exchanges with Wade’s Senegalese Democratic Party, aimed at strengthening its internal machinery. In 2016, Wade’s successor Macky Sall and Chinese President Xi Jinping elevated their relations to a “Comprehensive Cooperative Strategic Partnership,” the highest level of relations China can have with a foreign country. In 2017, Senegal became the first West African country to join China’s One Belt One Road Initiative (known internationally as the Belt and Road Initiative). That same year, the Senegalese military started procuring more modern Chinese armaments, which President Sall said were needed to respond to rising insecurity in the Sahel.

From 2018 to 2024, Senegal held the co-presidency of FOCAC, during which its military cooperation with China became as regularized as China’s more established defense partners like Egypt, Tanzania, and Nigeria. In 2023, the China North Industries Group Corporation Limited (NORINCO), a major Chinese defense firm, opened a regional office in Dakar, its fourth in Africa after Angola, Nigeria, and South Africa. NORINCO used this in-country presence to cement its role as a regular supplier to Senegal’s security sector and expand its operations in the Sahel, where it stepped up its supplies to Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.

In exchange for [security assistance], … African countries have helped advance China’s geopolitical ambitions.

Chinese security assistance to Kenya developed in similar ways, offering insights into how the PLA cultivates nontraditional partners. After expanding its arms exports to Kenya for 15 years, China designated Kenya as a “Comprehensive Cooperative Strategic Partner.” The growth in the share of Chinese weaponry in Kenya’s inventory from less than 3 percent in 1990 to 50 percent in 2018, represents a sea change in Kenya’s defense relations. Since independence in 1962, Kenya’s military partnerships have been dominated by ties to the United Kingdom and the United States.

A turning point in Kenya-China relations came in the 1990s, when then Kenyan President Daniel Arap Moi, who was seeking external support to preserve his rule, reached out to China. China responded by sponsoring intensive exchanges between the CCP and the Kenya African National Union between 1992 and 1995. These exchanges paved the way for meetings at the defense minister and military chief level in Nairobi and Beijing in 1996 and 1997, respectively.

Kenyan officers started attending Chinese military academies and staff colleges by 1999. By 2001, Chinese security assistance consisted of annual scholarships for Kenyan officers, military sales, joint exercises, peacekeeping, and support for Kenya’s officer academic institutions. This eventually extended to police cooperation, as is the case in over two dozen African countries.

By 2018, Kenya began permitting Chinese law enforcement organizations to conduct joint operations on Kenyan soil (largely targeting Chinese and Taiwanese nationals). In July 2021, China and Kenya launched a program to train 400 Kenyan security officers annually in China to include elite forces in the Presidential Guard, Directorate of Criminal Investigation, and General Service Unit. In addition to systematic party-to-party exchanges, China’s security assistance programs in Kenya also occurred alongside a large scholarship initiative for students, professionals, and government leaders, as well as one of Africa’s largest portfolios of Chinese-financed infrastructure projects.

In exchange, Kenya—like many other African countries—helped advance China’s geopolitical ambitions. Kenya voted alongside Chinese positions at the global level, supported the expansion of China’s One Belt One Road Initiative, and became an active partner in China’s Global Security Initiative. Moi’s rebalancing toward China, thus, has been continued under Presidents Mwai Kibaki, Uhuru Kenyatta, and William Ruto.

What African Governments Want from China’s Security Engagement

Nearly 40 African countries have some form of relationship with Chinese public security agencies. These include joint interdiction, protection of One Belt One Road assets, and extradition agreements. Many Chinese police institutions have training programs with African countries, including the People’s Public Security University, the China People’s Police University, and Shandong Police College. Between 2018 and 2021, roughly 2,000 African law enforcement officers received training in China.

Lieutenant General Antonio Lamas Xavier, Chief of Staff of the African Standby Force, speaks during a reception marking the 96th anniversary of the founding of the PLA in Addis Ababa on July 21, 2023. (Photo: Michael Tewelde / Xinhua / AFP)

African governments welcome Chinese security engagements for different reasons. For many, China is a source of affordable armaments with less stringent export controls and more flexible loan terms relative to Western suppliers. Some see China as a means of enhancing regime security. Others seek closer security ties to China as part of a hedging strategy.

A growing number of African countries have worked with China to develop their military industries in recent years. Algeria is working with Chinese firms to produce Type 056 PLA Navy corvettes domestically. Uganda has a joint venture with NORINCO to manufacture Chinese unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The Defence Industries Corporation of Nigeria (DICON) and NORINCO are working on a program to co-manufacture military grade ammunition. Such defense-industrial partnerships represent a new and growing area of Chinese security engagement in Africa.

African Perspectives on Chinese Security Engagement

African governments generally hold positive views of Chinese security cooperation as this is coupled with political support to the ruling party and enhancing regime security. African governments also tend to be supportive of Chinese arms and equipment, which are relatively available and affordable despite occasional complaints about quality and battlefield effectiveness. Between 2003 and 2017, 38 percent of the $3.56 billion that eight African countries borrowed from China for security purposes, were for domestic security. Chinese digital surveillance technologies are popular purchases and have been adopted by at least 22 African countries.

African democracy advocates, civil society, and media professionals generally do not share their governments’ enthusiasm for Chinese security engagements, citing the widespread abuse of Chinese policing and mass surveillance systems. China is also frequently criticized for its regime-centric strategy that many African observers believe entrenches authoritarian practices.

African civil societies are also integral to the scrutiny of these security relationships to ensure that they are advancing citizen interests.

As global geostrategic rivalries intensify, there are growing concerns that the enduring African demand for accountable and democratic government is increasingly being put aside in favor of transactional calculations last seen during the Cold War when security assistance was conditional on countries choosing sides.

Substantive African debates on Chinese security engagement have generally been limited due to difficulties accessing data for national security research. This is partly being overcome thanks to expanding independent Africa-China research networks. This is contributing to a growing body of African expertise on the PLA and the People’s Armed Police. This will contribute to greater African awareness, critical analysis, and public oversight.

Looking Ahead

China is expected to continue to expand its security engagements in Africa for the coming years to advance China’s growing geostrategic ambitions and to fill what it perceives as a vacuum of Western security assistance. The onus, therefore, will be on African societies to mitigate potential unintended consequences. Many African observers want to see better de-risking to ensure that increased Chinese security engagements do not undermine African interests, exacerbate tensions, or create insecurity.

Governments have a central role to play in this process by operating with greater transparency to disclose what is entailed in any agreement and to ensure it is in the best interests of their citizens. As an arms supplier, China has a special responsibility to vigorously enforce its export controls, especially when these arms are likely to be used against African citizens.

African civil societies are also integral to the scrutiny of these security relationships to ensure that they are advancing citizen interests. The expansion of African networks of experts on Africa-China relations, including security cooperation, is a welcome development toward this end as a means of generating greater public awareness to track, monitor, and report on Chinese security activities in Africa.

Additional Resources

- National Security Law Today, “Ports, Power, and China’s Strategy in Africa with Paul Nantulya,” Episode 370, National Security Law Podcast, May 14, 2025.

- Paul Nantulya, “The Growing Militarization of China’s Africa Policy,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 2, 2024.

- Allesandro Arduino, “China’s Expanding Security Footprint in Africa: From Arms Transfers to Military Cooperation,” Italian Institute for International Political Studies, September 30, 2024.

- Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, “Chinese Military Diplomacy,” database version 4.98, National Defense University, August 2024.

- Alex Vines, Henry Tugendhat, and Armida van Rij, “Is China Eyeing a Second Military Base in Africa?” Analysis, United States Institute of Peace, January 30, 2024.

- Paul Nantulya, “China’s “Military-Political Work” and Professional Military Education in Africa,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, October 30, 2023.

- Jana de Kluiver, “Can China be a More Attractive Security Partner for Africa?” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, September 25, 2023.

- Paul Nantulya, “China’s Growing Police and Law-Enforcement Cooperation in Africa,” essay from NBR Special Report No. 100, National Bureau of Asian Research, June 1, 2022.

More on: China in Africa