A herd of cows on the road to Bor, South Sudan. (Photo: BBC World Service)

When South Sudan achieved independence in 2011, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/ Movement (SPLA/M) and its leader, Salva Kiir Mayardit, took control of a system of governance that transcended the lines between the formal and informal sectors, military and civilian elites, government and nongovernment actors, as well as licit and illicit sources of revenue. Instead of laws, rules, regulations, and rights, South Sudan is governed through complex personal and familial ties with an uncertain fluidity. A military aristocracy was established that maintains its strength through patrimony made possible via resource capture.1 The SPLA/M was legitimized as liberators, and warlord-style rebel leaders were elevated to the top of a ruling class characterized by ethnicity.

The lack of legitimate political processes, combined with a monetarized and militarized system of governance, meant that any stability was always going to remain vulnerable to the competing demands of those able to use violence to project political power.2 When the existing governance fractures opened in December 2013, they manifested and continue to manifest as ethnic violence. This review of ethnicity and governance in South Sudan explores potential intervention strategies for international actors seeking to engage in stabilization activities in this conflict-affected state.

Ethnicity and Class

Instrumentalizing ethnicity for political gain often occurs in contexts where powerful actors see more relevance and efficacy in mobilizing along ethnic lines than along social classes. This is often related to the lack of desire of the ruling class for systemic change and the preference of elites—at various levels of society—for maintaining ethnically determined systems of production and consumption. As such, ethnicity should be understood as a political identity founded in social structures and reproduced by the institutions of the state.

A Mundari fisherman in Terekeka, Central Equatoria State. (Photo: UK Department for International Development)

Under the colonial state, South Sudanese were subjects divided into chiefdoms with a fusion of legislative, executive, and judicial powers conferred from the colonial state to the ethnic fiefdoms.3 The colonial administration used a form of ethnic federalism, aligning cultural and political boundaries, to manage native populations, not dissimilar to the approaches of Ethiopia and Nigeria today. Systems of ethnic federalism align identity and territorial divides creating options for more local autonomy while still leaving room for manipulation by the central state.

Under an independent Sudan, the dual legacy of the colonial state was reproduced in the Arab-African divide creating an ethnically diverse but unified opposition to the racialized state. However, internal tensions within the liberation movement were easily exploited, and Khartoum could deracialize the conflict and split the opposition into an ethnically fragmented array of armed actors, some of which were co-opted.

Independent South Sudan quickly began to mirror the class structure of Sudan with a small group of military elites exerting power through violence and patronage reliant on extended familial and ethnic ties. The depth of these ties is evident in the fluidity with which actors move across the state-nonstate and government-community boundaries.

Ethnicity and Rights

For actors at local levels, there is a continuous process of negotiating for rights awarded as privilege from the military elites. Since the colonial state, chiefs have played an important role as representatives of the community able to interface with the state. Importantly, this role was based on a denial of rights within an authoritarian system of governance with limited local power choices to affect access to resources and privileges. For citizens, relying on ethnically defined leadership is often more practical than looking for nonethnic institutions, especially when considering access to justice, security, and markets. When the state institutions fail to provide equity and predictability in their administration of rights, local institutions cross the “formal” and “traditional” dialectic, and laws and governance emerge.

Ethnicity and Identity

In African societies, identity is often created through both ethnic and market-based systems, with deep linkages between the two due to the nature of patronage.4 When looking at ethnicity as well as wealth transfers, one can understand the central roles that property and the ability to bestow “gifts,” particularly through bride wealth and dowry, play in maintaining the current governance system. While displacement and forced asset-stripping cause the seemingly never-ending humanitarian crises, these tactics provide visible evidence of the ways in which wealth is being continually consumed and transferred.

By independence, the SPLA had already become the primary space for resource accumulation, and wealth spread from the SPLA commanders through their kinship networks, most often through cattle and marriage. Instead of being a genuine national liberation movement, the SPLA turned into an agent of plunder, pillage, and destructive conquest. Operating more as an occupying force than a liberation movement or national army, the SPLA traditionally relied on local commanders—“business men of war”—able to coerce and co-opt local institutions for administration, taxation, and recruitment.5

Ethnicity and Governance: Emerging Recommendations

There are four main recommendations that emerge from situating ethnicity within a resource governance lens.

Human rights are central to state-citizen interaction. A core issue for any stabilization agenda is how to orient interventions to strengthen the human rights framework at local and national levels. The protection and advancement of human rights provide a bulwark against state excesses while also providing a means for citizens to claim social goods through lobbying, advocacy, and litigation. However, the current power dynamics require more than just adherence to rule of law or an independent judiciary. Meaningful change must come from fundamental changes in how the state and citizens interact. Technocratic institution and capacity-building approaches will need to interface with very complicated power dynamics at local and national levels.

Resources are important in order to delink ethnicity from governance. Thinking of South Sudan through ethnic and market-based identities opens avenues for delinking ethnicity from governance, as the military elites are created and sustained through productive relations and not merely through social identity. With this lens, there is the opportunity to explore linkages between production and ethnicity and the institutions that reinforce and/or resist the replication of those identities.

“There is a need to focus on the resilience, resistance, and innovation happening at the level of local institutions.”

The functionality of local institutions is essential. For many parts of South Sudan today, the state has not just penetrated the rural frontier but has through forced displacement and asset-stripping, tried to lay waste to the relative power of those home spaces. It is a war of domination run by a core inside the SPLA and the ruling party who enforce politicized ethnicity through violence and weaken law and order.6 While the state is pursuing a strategy of militarized and ethnic dominance, there is a need to focus on the resilience, resistance, and innovation happening at the level of local institutions.7 The focus should not be on ethnicity or ethnic representation, but rather on the functionality of local institutions to protect rights and resources and, importantly, how these institutions operate across and within the state-nonstate boundary.

The functionality of decentralization of access cannot be overemphasized. Ethnic dominance is enabled by a lack of functional decentralization tied to the territorial organization of the state and its administrative units. No matter the number of states, the division of South Sudan into administrative state units is a product of power and diversity. However, the essential geography and livelihoods of South Sudan mean that there can never be containment of diversity in ethnic fiefdoms, but rather that internal organization should seek ways to optimize interactions between peoples while also maintaining and harnessing local autonomy needs. This is what could be called a focus not on the lines on the map, but rather on physical decentralization and functional intercommunal linkages. Douglas Johnson notes that federalism will only thrive under hospitable conditions because it is a system of governance and not a political system.8 With the current political system based on militarization, monetarization, and turbulence, a federal system could just mean the difference between being ruled by one tyrant or by several petty tyrants.

The focus should not be on how many states or where the lines are, but rather on how to make economically and politically viable communities that are able to operate across ethnic boundaries. National identity and new cooperative norms will emerge from functional interactions between people and meaningful platforms for engagement. Centralization and the dominance of elite ethnic networks are enabled by the limited options that people have for most of their interactions. Even before the 2013 crisis, not all state capitals had banks, so people could not save money or access credit through the formal system. In the current conflict, market access has been extremely restricted to select groups.

Decentralization must physically expand the range of choices people have on the ground to step back from the patronage-based economic networks that operate within ethnically defined units. Indeed, many South Sudanese assert that the most obvious impediment to national cohesion is exclusion from the national platform, especially exclusion along ethnic lines.9 Formalizing terms of trade, regulating market behavior, and expanding access to credit, particularly in the form of cattle banks, could begin to dilute the importance of patrimony and ethnicity for access. In illicit and informal economies profit is generated and contained in closed networks that are often ethnically determined.

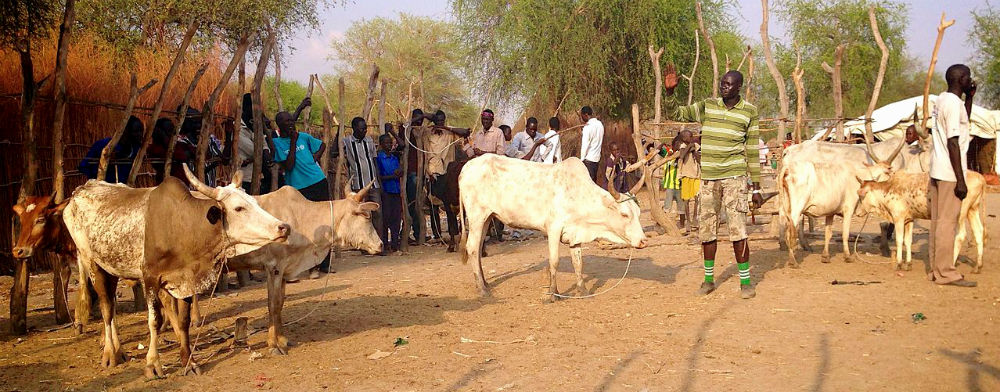

A cattle auction in Lankien, South Sudan. (Photo: Aimee Brown/Oxfam)

Conclusion

Stabilization may require delinking politics from ethnicity, but the foundation of the relationship between politics and ethnicity lies in the way in which the dominant ruling class has used the awarding of resources and rights to shape these dynamics. This is partly due to the closing of delineating spaces between the institutions of the home and state, but also due to the way in which resource accumulation limits nonviolent and de-ethnicized politics. The relevance of ethnicity in this conflict cannot be minimized without addressing the material systems that have enabled a form of ethnic extremism to take root. The state project is in crisis in South Sudan. Either the violent ethnic extremism that has become symbolic of the ruling regime continues its path of domination and destruction, or the frustrations of the excluded can find harmony with moderates on the other side to build a country based on mutual respect, rights, and regulations. Such platforms of cooperation could prove critical.

Notes

- ⇑ Clemence Pinaud, “South Sudan: Civil war, predation and the making of a military aristocracy,” African Affairs 113, no. 451 (2014), 192-211.

- ⇑ Alex de Waal, “When kleptocracy becomes insolvent: Brute causes of the civil war in South Sudan,” African Affairs 113, no. 452 (2014), 347-369.

- ⇑ Cherry Leonardi, Dealing with Government in South Sudan: Histories of Chiefship, Community and State (Suffolk: James Currey, 2013).

- ⇑ Mahmood Mamdani, “Political identity, citizenship and ethnicity in post-colonial Africa,” Working Paper presented at the World Bank Arusha Conference “New Frontiers of Social Policy: Development in a Globalizing World,” in Arusha, Tanzania, December 12-15, 2005.

- ⇑ Peter Adwok Nyaba, The Politics of Liberation in South Sudan: An Insider’s View (Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 1997), 51.

- ⇑ Madut Kon, “Institutional Development, Governance, and Ethnic Politics in South Sudan,” Journal of Global Economics 3, no. 2 (2015), 147.

- ⇑ Sharon E. Hutchinson and Naomi R. Pendle, “Violence, legitimacy, and prophecy: Nuer struggles with uncertainty in South Sudan,” American Ethnologist 42, no. 3 (2015), 415-430.

- ⇑ Douglas H. Johnson, “Federalism in the history of South Sudanese political thought,” RVI Research Paper No. 1 (London/Nairobi: Rift Valley Institute, 2014).

- ⇑ See Jok Madut Jok, “Diversity, Unity, and Nation Building in South Sudan,” Special Report No. 287 (Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace, 2011).

More on: Democratization Identity Conflict Stabilization of Fragile States South Sudan