Photo: Christopher Burns

A 21-country INTERPOL initiative known as Operation Jackal III targeting Black Axe, the Nigerian organized crime group, led to the arrest of 300 suspects and the seizure of $3 million in assets in a sting operation culminating in July 2024. While a victory for law enforcement, the action is unlikely to make a dent in the operations of Black Axe, which has an estimated 30,000 members in dozens of countries and yearly proceeds estimated to exceed $5 billion.

First founded in 1977 at the University of Benin in Edo State as a pan-African Black Power student confraternity, Black Axe has since morphed into a sophisticated multinational criminal enterprise with cells in the United States, Canada, Italy, Brazil, Argentina, Ireland, the United Arab Emirates, South Africa, France, the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands, among others. The organization also maintains a foothold in neighboring West African countries, such as Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, and can be found operating as far afield as China, Japan, Malaysia, and Singapore.

The proceeds gained from cybercrime have spawned a complex web of money laundering networks spanning the globe.

Known for its violence and brutality in Nigeria, Black Axe members (referred to as Axemen) routinely engage in drug dealing, smuggling, kidnapping, and extortion. Axemen also compete over territory with rival criminal groups—like the Maphites, the Supreme Eiye Confraternity, and the Vikings—and are accused of perpetuating a culture of urban violence, political corruption, and juridical impunity. Nigeria recorded almost 6,000 gang-related deaths across 31 states from 2006 to 2021.

In its operations abroad, Black Axe members engage in crimes such as drug-trafficking, extortion, and sex worker management. The organization’s most profitable criminal enterprise, cybercrime, transcends geographic boundaries and is thought to have netted the organization tens of billions of dollars. Starting out as simple “Yahoo Boys” pulling advance-fee scams via email, many Black Axe members have grown into shrewd cybercriminals who specialize in defrauding businesses out of thousands if not millions of dollars. The proceeds gained from cybercrime have, in turn, spawned a complex web of money laundering networks spanning the globe.

Sophisticated Structure and Diversified Portfolio

Cybercrime

(Image: Rawpixel)

INTERPOL has identified Black Axe as one of the leading criminal actors responsible for cyber-enabled financial fraud globally. Axemen began by transferring preexisting “419” cash-advance scams (in which, say, a fictional Nigerian Prince needs money to access his inheritance) to the internet in the mid-1990s. By the 2010s, Black Axe members were involved in more sophisticated forms of online fraud, including business email compromise (BEC), a scam that tricks victims into sending money or divulging confidential company information. For example, Axemen stole €91,000 (roughly $98,000) from an Irish plastics manufacturer by impersonating one of their suppliers. Another scheme saw fraudsters pose as concert promoters to defraud the Spanish distributor Imprex of €294,000 (roughly $317,000).

These sums might seem like a drop in the bucket for large firms, but the figures add up. The United States’ Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) arrested 13 Black Axe members in 2019 responsible for stealing more than $10 million via cybercrime. The FBI subsequently apprehended 33 Black Axe operators who stole upward of $17 million using BEC and other forms of cyberfraud in 2021. One might think that leading international firms would be too smart to fall for such tactics, but Black Axe is thought to take in between $300-500 million per year using BEC scams in North America alone.

As one observer noted, Black Axe went from “short-con to long-con” from “pickpocket to bank heist” using similar methods of deception they employed with the “419” scams.

Money Laundering

Black Axe member posing with Nigerian currency. (Photo: Nigerian View)

The expansive nature of Black Axe’s cybercriminal activity has begotten an impressive global money laundering enterprise. For instance, when Axemen defraud a target abroad, they usually instruct the victim to send the money to an in-country account to avoid the suspicion of sending it to a Nigerian bank. The group then uses an intermediary or “linkman” to transfer the money from said account over to Black Axe’s network of money launderers without attracting the attention of financial regulators. Once they receive the money, Black Axe launderers diffuse the funds into a host of different investments.

One scheme popular in North America is for launderers to buy cars and ship them to Nigeria. Another ploy is to purchase real estate, which drives up housing prices and squeezes out home buyers. These ill-gotten funds may also be invested into business enterprises, outcompeting law-abiding firms who lack access to this capital. Cryptocurrency—which affords owners near anonymity and can be sent instantaneously between digital wallets around the world—is also a key part of Black Axe’s money laundering strategy.

Black Axe launderers and linkmen thrive in countries with lax fiscal regulations and oversight. One of these hubs is Ireland where Nigerian linkman Junior Boboye helped launder several million dollars’ worth of funds for Black Axe before his apprehension in 2018. Another favored location is the United Arab Emirates where successful Black Axe affiliated launderer Ramon Abbas openly advertised his services and flaunted his wealth on Instagram before his arrest in 2020. Known as “Hushpuppi,” Abbas operated out of Dubai and not only helped to launder money for Black Axe but also for the Lazarus Group—the notorious North Korean hacker cabal responsible for the 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack. While there have been no publicly declared arrests in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Black Axe internal communications show that its money routinely passes through bank accounts in Hong Kong and mainland China due to the PRC’s “nonexistent money laundering checks.”

Black Axe launderers and linkmen thrive in countries with lax fiscal regulations and oversight.

Though Black Axe launderers prefer to operate in more fiscally opaque areas of the world, they can do business anywhere and often hide in plain sight. Ikechukwu Amadi, a resident of Mississauga, Ontario (Canada), was jailed in 2019 for his participation in a $5-billion money laundering scheme. Ghaleb Alaumary, a wealthy resident of the same quiet Toronto suburb, was sentenced in the United States in 2021 for laundering tens of millions of dollars stolen using various wire transfer and bank fraud schemes.

Violence and Criminality in Nigeria

In Nigeria, Black Axe is known not as a sophisticated, white-collar criminal organization but rather as a violent gang. Images of their enemies’ corpses routinely appear in the press and on social media, striking terror and outrage in the hearts of Nigerians across the country. In large cities like Lagos, Port Harcourt, and Benin City, citizens face threats of violence, rape, and extortion from Black Axe members and risk being caught in the crossfire of intergang warfare. Fatalities linked to such gang violence are estimated to have doubled since 2019. Others worry their children will be killed or one day indoctrinated into the criminal organization.

Nigerian police arrest three Black Axe gang members. (Photo: Punch)

This concern is not unfounded given that Black Axe and other gangs typically recruit new members from universities and secondary schools. Known locally as a cult, Black Axe is infamous for its shadowy and sinister initiation practices, during which pledges are often beaten unconscious or sometimes instructed to murder a stranger or even a family member. After being invited in, initiates swear an oath to Korofo, “the unseen God,” and gain proximity to an underground world of black magic practitioners and juju, the use of which Nigerians both fear and revile.

Once in the gang, it can be very difficult to break free. Deserters can face violent reprisals at the hands of old comrades or come under attack from rival groups after forsaking cult protection. Others join vigilante associations that end up perpetuating the endless cycle of violence by taking the fight to gang members.

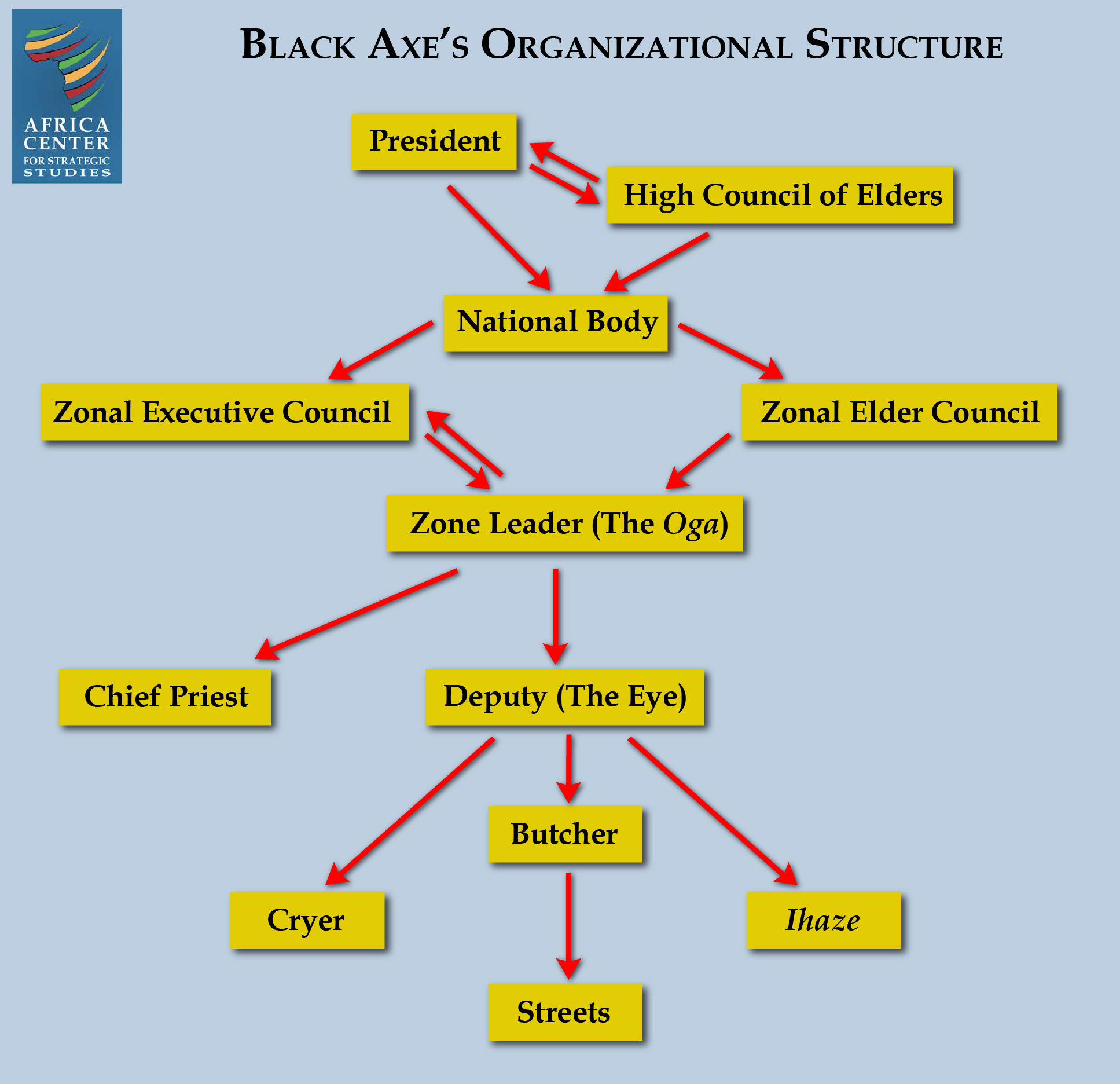

Organizational Structure

Black Axe operates within a complex and opaque organizational structure. In Nigeria, people often view Black Axe as synonymous with its legal parent group, the Neo-Black Movement of Africa (NBM). NBM is a confraternity registered with the Nigerian Corporate Affairs Commission and has over one million members. While NBM affords the same array of social and professional networking as other confraternities, the group is undoubtedly buoyed by illicit Black Axe funds. One could therefore think of Black Axe as NBM’s criminal wing.

Exploiting vulnerable members of the Nigerian diaspora is a key part of Black Axe’s operations.

Much remains unknown of Black Axe’s organizational structure, though it is led by a president who oversees the Black Axe hierarchy with a high council of elders. Operationally, Black Axe is managed by a national body comprised of a separate council of elders and a zonal executive council headed by a chairman.

This structure presides over zone leaders who manage operations in specific geographic areas. There are an estimated 60 zones covering every major Nigerian municipality. Internationally, there are believed to be 6 zones in North America, 2 in South America, 7 in Asia, 16 in Europe, and 4 in Africa. International zones are sometimes organized by country, other times by city. There are also more specialized roles: chief priests organize rituals and make amulets for members’ protection; butchers enforce discipline and organize attacks against rivals; “cryers“ oversee communications; and “ihaze” function as cells’ treasurers. Below them is a layer of soldiers or “streets” who are used as footmen in criminal operations and are expected to pay money up the chain to leaders or “socials.”

Black Axe’s organizational structure tends to be more adaptive and opportunistic in the field of cybercrime. As one security official who tracks Black Axe observes, Axemen “may be working with some guys one week, [but the] next week they’re working with some other guys.” Another expert notes that “an individual leading one operation [for Black Axe] may seamlessly transition to a subordinate role in a different [cyber] criminal endeavor [… and this lack of hierarchy extends] to the remuneration structure, where, unlike traditional organized crime, compensation for BEC roles is variable and dependent on the perceived value of each function.”

Black Axe’s foreign cells operate more autonomously and often will not send money back to the national body in Nigeria. This has contributed to tension within the organization and caused the national body to place a ban on recruitment in Europe and particularly in Italy where the Cosa Nostra and the Camorra mafia syndicates allow local Black Axe cells to operate on their territory in exchange for a cut of their profits.

Exploiting vulnerable members of the Nigerian diaspora is a key part of Black Axe’s operations. Axemen routinely coerce or convince Nigerian migrants to take part in their money laundering activities. Sometimes this consists of forcing migrants to use their bank accounts to receive ill-gotten funds. In other instances, migrants become veritable “money mules” who help to funnel cash to launderers. In South America, Black Axe similarly uses Nigerian and Venezuelan migrants to traffic cocaine to Nigeria and Europe via plane. Finally, Black Axe has been involved in the prostitution of Nigerian women, as part of the sex trafficking industry in Italy and France.

Neopatrimonialism in Nigeria

Black Axe exploits vulnerable populations, particularly young men, in Nigeria as well. Here, it uses young, low-level gang members, known as “streets,” to fight over territory, control illicit markets, and steal oil from pipelines. Oil bunkering in Nigeria is estimated to have generated $46 billion in proceeds between 2009 and 2020. Funds gained from such illicit activities allow Black Axe’s leadership to integrate themselves within the Nigerian political system and forge networks of patrimonialism.

Funds gained from illicit activities allow Black Axe’s leadership to integrate themselves within the Nigerian political system.

The roles certain Black Axe leaders play in both overseeing Black Axe’s criminal activity and Nigerian political life highlights the challenges of investigating and prosecuting Black Axe in Nigeria. Evidence leaked by hacker “Uche” Tobias demonstrates that Bemigho Eyeoyibo was both the president of NBM and the head of Black Axe from 2012 to 2016. Even after this information was made public, Eyeoyibo was allowed to run for office as a member of the All Progressives Congress (APC) in 2019. Another well-known Axeman, Tony Nwoye, reportedly stole state funds for Black Axe but was permitted to remain chairman of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) in Anambra State. Finally, the prominent “godfather” of Edo State, Tony Kabaka, who is a member of both NBM and the APC, is also thought to be affiliated with Black Axe.

Securing the support of godfathers like Kabaka is tremendously important for politicians in Nigeria. Godfathers provide politicians with money and political machinery to mobilize support for candidates. Some may also use manpower from gangs and criminal groups like Black Axe to intimidate opponents and serve as enforcers. In return, political proteges grant godfathers access to public funds and political influence once elected.

Constraints in Prosecuting Black Axe

(Photo: Ogun State House of Assembly)

While INTERPOL has successfully coordinated sting operations against Black Axe abroad, efforts to curb Black Axe in Nigeria have been largely unsuccessful. The federal government enacted the Secret Cult and Similar Activities Prohibition Act in 2004, which serves as a blueprint for countering illicit cultist activity. Several other states have also passed laws outlawing cultism with Edo State police deploying a Special Task Force on Anti-Cultism. In 2021, Lagos State’s governor signed a new law that would punish the parents of youths convicted of involvement in cult-related activity.

These policy actions demonstrate a degree of political will to confront Black Axe within Nigeria. Many Nigerians despise and feel directly threatened by criminal groups like Black Axe. Communities across the country have spearheaded efforts to mobilize traditional, educational, and religious institutions to dissuade young men from criminal activity. Vigilante groups also round up suspected gang members and deliver them to local police. These efforts have resulted in thousands of low-level arrests. However, a culture of impunity persists around prosecuting criminal groups like the Black Axe given that that many senior officials, jurists, and law enforcement officers at both the state and federal level are confraternity members.

A culture of impunity persists around prosecuting criminal groups like the Black Axe given that that many senior officials, jurists, and law enforcement officers are confraternity members.

Groups like NBM along with the National Association of Airlords and the Green Circuit Association (the respective legal parent organizations of the criminal Supreme Eiye Confraternity and the Maphites) have millions of members. Membership to precolonial secret societies like the Ogboni and Owegbe, which tend to work against state interests, can be joined while also being a confraternity member.

Nigeria therefore sees few convictions with one police commissioner in Edo saying, ‘‘each time we arrest members they remain in custody and then we receive a call … [from] people at the top level of state government, politicians … we have to liberate them.” Meanwhile, lacking oversight, state-level police and security forces often use anti-cultist legislation to crack down on legitimate student movements and youth protests.

Lessons from Fighting Criminal Organizations Elsewhere

Italy is perhaps the most important success story of a country that managed to effectively confront ubiquitous and embedded criminality. In 1982, the Italian Parliament enacted Article 416-bis of the Penal Code which defined mafia-type organizations and established minimum prison sentences for those found to belong to such groups. The country also established the Anti-Mafia Investigation Directorate (DIA), the National Anti-Mafia and Anti-Terrorism Directorate (DNA), along with the Anti-Mafia Code in 2011 that allowed law enforcement to strike at the financial foundations of mafia operations by making it easier for police to seize ill-gotten money and valuables.

Suspected Black Axe members are arrested by local police and Interpol in 2024 as part of Operation Jackal III. (Photo: Interpol)

Italy also relied on nonstate actors (including the private sector and the Church) and civil society organizations like Addiopizzo and Libera to protect mafia victims and informants, support businesses affected by racketeering, and redistribute confiscated assets to communities. These actions eroded the tacit support criminal organizations once enjoyed in country’s south and helped Italy overcome its historic “mafia culture.”

In other instances, progress against organized crime has come because of international cooperation. In 2006, for instance, the government of Guatemala and the United Nations established the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), building the Guatemalan judiciary’s capacity to confront political corruption and criminal gangs. The CICIG had some notable successes: it prosecuted dozens of high-level cases, identified 70 criminal structures, and possibly prevented between 20,000-30,000 deaths. CICIG was ended in 2019 by then President Jimmy Morales after the Commission began investigating his campaign for illicit financing. The CICIG has since been criticized by some for failing to reform the Guatemalan judiciary, improve police investigative capacity, and bolster public prosecutors’ ability to crack down on organized crime.

Other initiatives have emphasized equipping state judiciaries with the necessary tools to help them confront organized crime independently. Before it was terminated by the Malian military junta in 2023, the UN peacekeeping operation, MINUSMA, established the Judicial Unit for Terrorism and Transnational Organized Crime that aimed to provide Malian prosecutors and law enforcement with logistical and informational support needed to prosecute criminals, terrorists, and their political sponsors.

A 2024 initiative in Haiti, supported by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, succeeded in creating new “judicial pools.” These are legal bodies comprised of local prosecutors who are given financial and operational resources from international partners to fast-track important cases and act against leading criminals. Under UN Resolution 2653, the Haitian government has also worked with foreign actors, particularly the United States and Canada, to impose targeted sanctions on violent gangs’ key political patrons.

Overcoming Impunity to Combat Black Axe

Given the political interference limiting prosecutions of Black Axe crimes in Nigeria, the federal and state governments will need to augment their existing legislation to better insulate the judiciary from criminal intimidation. This may entail establishing an autonomous judicial unit to prosecute leading Black Axe figures and their political allies. Nigeria may also consider working with international partners to impose sanctions on public figures recognized as Black Axe patrons to reduce the political leverage these figures wield, as was done to prominent gang sponsors in Haiti.

Combatting Black Axe will also entail a major public outreach campaign enlisting community, religious, traditional, and educational leaders to raise awareness of the threat posed by criminal organizations immersed within confraternities—and dissuading youth from joining.

Scrutiny is needed on governments in China and the United Arab Emirates that serve as major financial transfer hubs for Black Axe’s illicit transactions.

At the international level, INTERPOL’s multicountry operations have hindered Black Axe’s activities and will remain important. INTERPOL may also consider widening its net of international police partnerships to include more African countries given that Black Axe maintains a presence in several African countries that were not a part of its previous operations.

Businesses in Africa and abroad could also do more to sensitize their employees to BEC scams. Companies could likewise consider using software that recognizes suspicious emails and deploys chatbots to allow law enforcement to gather information on their activities.

Finally, growing scrutiny is needed on governments in China and the United Arab Emirates that serve as major financial transfer hubs for Black Axe’s illicit transactions. Stronger fiscal oversight within these financial hubs could significantly constrain Black Axe’s financial flows, cutting into its revenue streams and operational capacity.

Dr. Matthew La Lime is a Research Associate with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Additional Resources

- Goeff White, Rinsed: From Cartels to Crypto: How the Tech Industry Washes Money for the World’s Deadliest Crooks (London: Penguin Books, 2024).

- Suleman Lazarus, “Cybercriminal Networks and Operational Dynamics of Business Email Compromise (BEC) Scammers: Insights from the ‘Black Axe’ Confraternity” Deviant Behavior (2024), 1-25.

- Charlie Northcott, “World’s Police in Technological Arms Race with Nigerian Mafia” BBC, August 27, 2024.

- “Black Axe: Nigeria’s Mafia Cult,” BBC Africa Eye Documentary, BBC, December 10, 2022.

- Nate Allen, Matthew La Lime, and Tomslin Samme-Nlar, “The Downsides of Digital Revolution: Confronting Africa’s Evolving Cyber Threats” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, December 2022.

- Corentin Cohen, “Nigerian Confraternities Out to Conquer the World?” Les études du CERI N˚ 258 bis, SciencesPo, December 2021.

- Sean Williams, “The Black Axe: How a Pan-African Freedom Movement Lost Its Way” Harper’s Magazine, September 2019.

- Stephen Ellis, This Present Darkness: A History of Nigerian Organized Crime (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

More On: Nigeria