The UN Security Council unanimously adopts Resolution 2719 on cooperation between the UN and the African Union. (Photo: UN/Eskinder Debebe)

The passage of United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution 2719 (UNSCR 2719) on December 21, 2023, has created a new chapter for peace operations in Africa.

UNSCR 2719 provides a framework for peace operations led by the African Union (AU) to access UN funding through assessed contributions. This has the potential to make peace operations more effective and sustainable while enhancing African leadership in managing them. It was necessitated in part by a decline of UN peacekeeping and a shift to African-led missions. While these missions have had a measure of success in addressing Africa’s armed conflicts, they tend to lack the resources, expeditionary capabilities, and civilian infrastructure typical of UN peacekeeping. By enabling African-led missions to access UN financing, UNSCR 2719 provides an opportunity for both the UN and AU to innovate the tools, practices, and partnerships needed to address Africa’s armed conflicts.

By enabling African-led missions to access UN financing, UNSCR 2719 provides an opportunity for both the UN and AU to innovate the tools, practices, and partnerships needed to address Africa’s armed conflicts.

The product of over 15 years of negotiations, UNSCR 2719 comes at a time of flux and uncertainty for peace operations in Africa. Spiraling Islamist militancy and civil wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), northern Mozambique, the Sahel, Somalia, and Sudan are taking a devastating toll. The persistence of armed conflict, despite the AU’s aspiration to end all wars on the continent, have contributed to a growing sense of disillusionment with multilateral peace operations and with the AU. These frustrations are in part due to a gap between what citizens expect of peace operations and what they can deliver as effective, yet limited, tools to manage conflict. This gap reflects the need for better collective responses to the security challenges gripping Africa.

The Winding Path to Assessed Contributions

The AU first requested UN-assessed contributions in 2007 to support the peace operation that became the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID). Since that time, the issue has gained traction in fits and starts. Agreement in principle about the importance of the UN providing predictable, sustainable, and adequate funding to the AU has been weighed down by concerns about burden-sharing, financial transparency, and AU compliance with international law.

A Ghanaian police officer, part of UNAMID, with school children at the El Sereif IDP camp in South Darfur. (Photo: UN/Albert Gonzalez Farran)

UNSCR 2719 provides a broad framework for deepening the AU-UN partnership. Prior to any AU mission backed by UN financing, the UN and AU will have to undertake a joint strategic assessment, after which the AU will prepare a draft concept of operations in consultation with the UN Security Council and host country. The Security Council would then decide whether to authorize the mission. Detailed planning would be undertaken jointly by the AU and the UN, and the mission must be compliant with both UN and AU financial regulations, accountability mechanisms, and human rights frameworks. Any mission would be under the “direct … and effective command and control of the African Union.”

When a peace operation loses popular support, it is less able to fulfill its mandate.

Facing a plethora of conflicts in the region, the AU and UN must wield UNSCR 2719 prudently. The pioneering cases of AU-led peace support operations using assessed contributions will carry a burden of expectations that, if left unmet, could undermine confidence in Africa’s multilateral institutions. Due to the severity and intractability of the crises they confront, peace operations are rarely risk-free endeavors. Rather than stake all on a single “test case,” accordingly, the UN and AU ought to apply assessed contributions in a variety of contexts, experimenting and innovating along the way. Decades of experience with UN peacekeeping, AU-led peace support operations, and partnership between the two organizations, offer numerous lessons that can inform the implementation of UNSCR 2719.

Criteria for Selecting UN-Assessed Missions

Several key criteria will likely weigh heavily on the AU and UN’s decision to apply UNSCR 2719:

- Host government consent. Host government consent is a vital factor for the success of nearly every peace operation. Without it, peacekeepers may face resistance, hostility, or even direct confrontation from local authorities, undermining the mission’s mandate and endangering the safety of personnel. This consideration is not always straightforward, however. Governments change and may not control large swathes of a country’s territory. Moreover, the move to shut down peace operations is often aimed at reducing accountability of host nation security forces for abuses against civilian populations. Such instances present thorny questions over who represents the interests of citizens.

- Political processes. Peace operations are most effective when they are used as tools to foster or implement peace agreements or political settlements. The United Nations, for example, tends not to deploy peacekeepers without a ceasefire or peace agreement in place. The African Union has a more aggressive doctrine and will deploy in contexts where there is little to no peace to keep. Lessons from AU and UN missions show that, while these “peace enforcement” operations can be effective in containing threats and saving lives, warfighting without pursuing the “political” elements of peacekeeping rarely ends in long-term conflict resolution.

- Regional consensus. Peace operations are most effective when there is regional consensus. Nevertheless, key regional actors may disagree about the need for a peace operation, while some may be directly or indirectly involved in a conflict. Navigating the politics of these interests when considering peace operations as well as the actions neighboring governments may take as spoilers are central to effective peacekeeping.

- Popular support. Popular support for a peace operation is essential. Though securing consent of communities affected by conflict is not a formal part of peacekeeping doctrine, peacekeepers are often mandated to protect civilians from harm and routinely engage civil society. When a peace operation loses popular support, it is less able to fulfill its mandate. Modern peace operations increasingly face targeted disinformation campaigns aimed at undermining their credibility employed by domestic actors eschewing accountability or external actors seeking greater leeway.

These criteria provide a starting point for thinking about the conditions under which to deploy a peace operation and how to craft a mandate to maximize an operation’s chances of success. They are not absolute, however. It may be rare for any peace operation to clearly meet all four criteria. Moreover, operations have succeeded in their absence. For example, with neither a peace agreement nor consent from the de facto government, the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) retook Freetown, Sierra Leone, from the Revolutionary United Front rebel group, and reinstated President Ahmad Kabbah, who had been overthrown in a coup. This 1997 intervention paved the way for a peace accord that facilitated lasting peace.

A MINUSMA interpreter assists an officer talking to a villager during a patrol. (Photo: MINUSMA/Harandane Dicko)

The fact that peace operations deploy in difficult, contested, and shifting circumstances can also lead to trade-offs. This was a conundrum faced by the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) after a faction of Mali’s military seized power in 2020. Following UN-backed allegations that human rights abuses by Malian forces led to the deaths of 500 unarmed civilians in the town of Moura, Mali’s military government ordered peacekeepers to leave on an accelerated timeline under dangerous circumstances. The incident brought to fore tensions between MINUSMA’s mandate to support the extension of government control over territory and responsibilities to protect civilians on the receiving end of government abuses.

The limited presence of any criteria should not necessarily disqualify deploying or continuing a peace operation. It should, however, be identified as a potential challenge and addressed proactively.

Lessons from Past Peace Operations

Past peace operations provide additional lessons that should be applied to future AU missions accessing UN-assessed contributions. As the most significant joint AU-UN peace operation partnerships to date, the experiences of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) and the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) are particularly instructive.

A first lesson is that the partnership between the AU and the UN will not always be equal. UNAMID was the first and only hybrid AU-UN mission, with both the AU and the UN given joint responsibility over many aspects of the operation. UNAMID’s mission head reported to both the UN secretary-general and the AU Commission chairperson. Unfortunately, this led to communication breakdowns, gridlock, and differences in priorities that were exploited by an increasingly hostile Sudanese government. It is perhaps with this lesson in mind that UNSCR 2719 specifies that missions receiving assessed contributions be under AU command and control.

A second and related lesson is that both the UN and the AU should enhance each party’s comparative advantages. The UN, for example, has a clear advantage in providing logistical support and enabling capabilities. This is evident from the experience of the UN Support Office for AMISOM (UNSOA). When the UNSOA first entered Somalia in June 2009, AMISOM personnel were living in the bush with no tents, mess halls, or latrines. By providing shelter, food, and rations as well as specialized capabilities such as helicopters, medical evacuation, and counter-improvised explosive device capabilities, first to AMISOM and eventually to Somalia’s national government, the UN made significant and lasting contributions to the mission.

The AU, by contrast, should supply most of the troops and may be best suited to take the lead in political negotiations. This was the AU’s main contribution to UNAMID, where the Sudanese government insisted that any peacekeeping operation be led and staffed by Africans, and where the AU’s leadership was critical in negotiating peace agreements in 2006, 2011, and 2020.

A third lesson is that logistical support needs to suit mission requirements. The UN’s logistical support office in Somalia found this out in the early stages of its support to AMISOM, where the inability to provide lethal support and underestimation of the amount of supplies required for up-tempo offensive operations was a constant source of tension with troop-contributing countries. If the UN cannot supply the kinds of equipment needed for such operations, and troop-contributing countries or other external partners are unable to fill the gap, then the AU will need to revisit its concept of operations. In cases where lethal support or UN police or civilian personnel might be useful, a hybrid AU-UN mission with accompanying efforts to build AU capacity in these domains may be the right approach.

A fourth lesson is that peace operations tend to be more effective when one troop-contributing country (TCC) leads. This is a common practice in regional economic community-led peace enforcement operations, from Senegal’s leadership of the Economic Community of West African States Mission in The Gambia (ECOMIG) to South Africa’s role in the Southern African Development Community Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) to Nigeria’s role in the Lake Chad Basin Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF). In each case, one country, with support from others in the region, took the lead in commanding a peace operation. This coordinated process contrasts markedly from larger, multidimensional operations, which can suffer from a lack of a unified command structure. Future peace operations should have one “lead” TCC in command of the operation with simultaneous command over logistical support.

Applying the Lessons

How might these lessons factor into contexts where the new UNSCR 2719 framework could be applied?

A Somali police officer and a member of ATMIS after a patrol in Mogadishu. (Photo: ATMIS/Mukhtar Nuur)

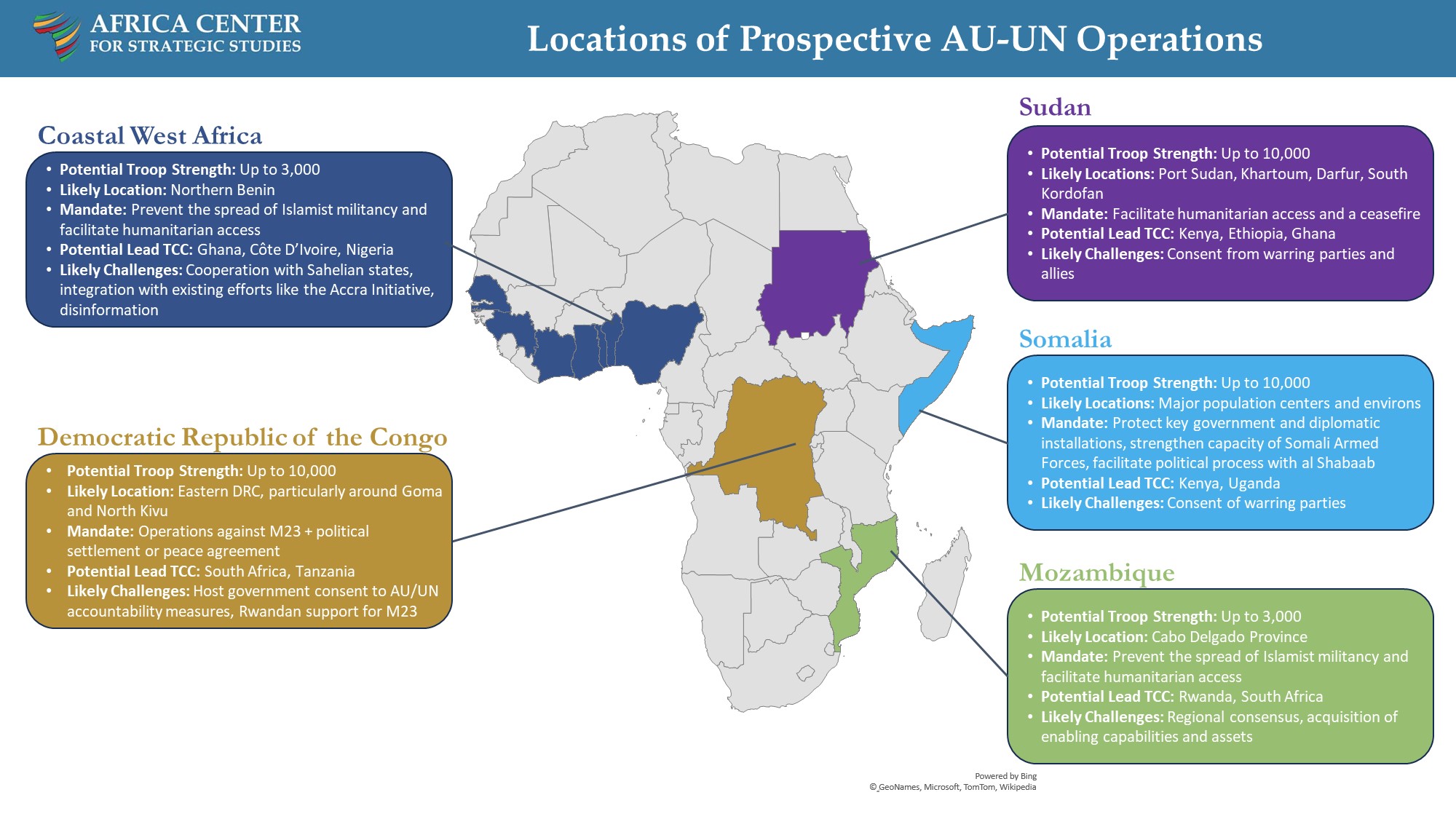

With the mandate of the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) set to expire in December, a UNSCR 2719 mission in Somalia will likely be up for consideration. Without a new mission, al Shabaab could well regain the initiative. Somalia has requested a scaled-down AU mission focused on protection with UN logistics support to strengthen national systems and capacity. Such a mission authorized under UNSCR 2719 would have strong host nation and regional support. It would also draw on the established presence of ATMIS. Given that the conflict has persisted for more than a decade, however, it may face skepticism within the Security Council and would need to be integrated with a clear political path forward.

Another context for the use of assessed contributions is coastal West Africa, which faces encroachment from Islamist militants that now control considerable territory in Burkina Faso and Mali. Among the coastal countries, Benin is most at risk. Such a mission would likely benefit from host government, popular, and regional support. However, given concerted Russian-sponsored efforts to undermine the credibility of UN peacekeeping in the Sahel, if mandated, such a mission would need to invest in robust counter-disinformation capabilities.

Northern Mozambique is another candidate to receive assessed contributions. The SAMIM and Rwandan Defense Forces have helped stabilize but not neutralize the threat from militant Islamist groups. An AU-led mission under a lead TCC could tap assessed contributions to add critical enabling capabilities, civilian expertise, and deepen coordination with humanitarian actors seeking to protect civilians and consolidate gains.

The move to shut down peace operations is often aimed at reducing accountability of host nation security forces for abuses against civilian populations.

The eastern DRC is a further context for consideration. The DRC government has asked the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) to leave—seen in part as an effort to remove a layer of oversight for actions by the DRC’s armed forces against civilians. MONUSCO also has been the target of disinformation. Regional forces from the East African Community and then the Southern African Development Community have aided the effort to contain the resurgent M23 rebel group. A UNSCR 2719 mission involving assessed contributions that maintains a focus on peacekeeping in some regions with a more offensively minded mandate in others would likely receive host country consent and support from many countries in the region. It may even be able to facilitate progress toward a political settlement were it also mandated to attempt to establish a ceasefire or peace agreement with the M23.

An additional context that may be considered for an assessed-contribution mission is Sudan. An AU-led or hybrid AU-UN mission could help provide desperately needed humanitarian access, monitoring and reporting on the ground, and mediation between Sudan’s warring parties. Over time, it may be able to help lay the groundwork for a ceasefire or peace agreement across the expansive conflict stretching from Darfur to Port Sudan and Khartoum to South Kordofan. Sudan’s neighbors, who are suffering spillover from the war, are also likely to support, or at least not oppose, an AU-led mission. The biggest obstacle to any mission is likely to come from the conflict’s two main warring parties, the Rapid Support Forces and the Sudanese Armed Forces. They may not agree to the presence of any peace operation without major arm-twisting by their international backers.

Looking Ahead

These lessons offer insights on how the next generation of peace operations deployed by the AU and UN might differ from previous ones.

Future peace operations will seek clearer delineations of responsibilities to maximize the comparative advantages of both the UN and the AU. The AU will be in command of predominantly African troop-contributing countries with the UN enabling capabilities and providing logistical support and financial and legal oversight. This requires, in the near term, that the AU and UN finalize the financial and burden-sharing elements of UNSCR 2719. Over time, this may require further reforms over how the UN provides logistical support and how the AU contributes troops to peace operations.

This analysis highlights the importance of going beyond the military-centric paradigm that has motivated many peace operations in Africa in recent years.

Given these considerations as well as financial constraints, it is also likely that new AU missions employing assessed contributions will be modest in size, with anywhere from several hundred to several thousand authorized troops. This is a far cry from the major peace operations of the past two decades, which often saw sustained deployments of over 20,000 peacekeepers. Nonetheless, the size or duration of a peacekeeping mission is not necessarily correlated with its success. A shift to smaller missions may also help manage expectations about what peace operations can accomplish.

This analysis also highlights the importance of going beyond the military-centric paradigm that has motivated many peace operations in Africa in recent years. Instead, they will have to focus on what peace operations historically do best—foster ceasefires, political settlements, and peace agreements, and serve as a crucial voice for and conduit between military and civilian actors in times of war.

UNSCR 2719 offers the UN and the AU a powerful new tool to promote peace. It is now up to African member states, with support from the international community, to realize its potential.

Dr. Nate Allen is an Associate Professor at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies who oversees the Center’s programs on peace operations.

Ms. Nicole Mazurova is an Academic Associate with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Additional Resources

- Eugene Chen, “Next Steps on the Financing of African Peace Support Operations: Unpacking Security Council Resolution 2719 (2023),” Center on International Cooperation, February 2024.

- Daniel Forti and Liesl Louw-Vaudran, “The Security Council Agrees to Consider Funding AU Peace Operations,” International Crisis Group, February 15, 2024.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The State of United Nations Peacekeeping in Africa,” interview with General Birame Diop, Military Advisor in the United Nations Department of Peace Operations, February 19, 2024.

- Security Council Report, “In Hindsight: The Financing of AU-led Peace Support Operations: Assessing Council Dynamics and Anticipating Future Action,” February 2024 Monthly Forecast, January 31, 2024.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 2719, S/RES/2719 (2023), adopted by the Security Council at its 9518th meeting, on December 21, 2023.

- Nate D.F. Allen, “African-Led Peace Operations: A Crucial Tool for Peace and Security, Spotlight,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 9, 2023.

- Paul D. Williams and Arthur Boutellis, “Partnership Peacekeeping: Challenges and Opportunities in the United Nations–African Union Relationship,” African Affairs 113, no. 451 (2014).

- Paul D. Williams, “Peace Operations in Africa: Lessons Learned since 2000,” Africa Security Brief No. 25, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2013.

More on: Peacekeeping