Download PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Ethnic conflicts in Africa are often portrayed as having ages-old origins with little prospects for resolution. This Security Brief challenges that notion arguing that a re-diagnosis of the underlying drivers to ethnic violence can lead to more effective and sustainable responses.

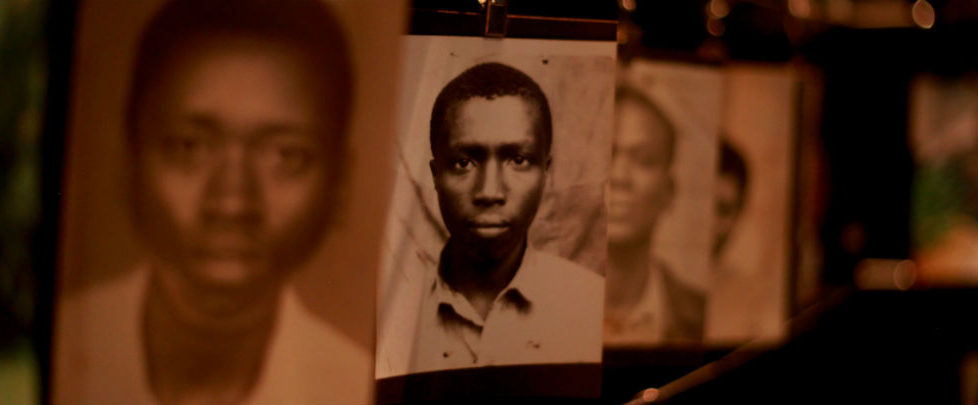

Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre. Photo: Trocaire.

Highlights

- Ethnicity is typically not the driving force of African conflicts but a lever used by political leaders to mobilize supporters in pursuit of power, wealth, and resources.

- Recognizing that ethnicity is a tool and not the driver of intergroup conflict should refocus our conflict mitigation efforts to the political triggers of conflict.

- Ethnic thinking and mobilization generally emerge from inequitable access to power and resources and not from an intrinsic hatred.

- Over the medium to long term, defusing the potency of ethnicity for political ends requires a systematic civic education strategy that helps build a common national identity, which so many African countries still lack.

There is a general perception that Africa is trapped in a never-ending cycle of ethnic conflict. The Rwandan genocide, Darfur, northern Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, and the violent aftermath of the controversial Kenyan elections, among other cases, seemingly substantiate this perception. As grievances accumulate and are defined at the group rather than individual level, the motivation for reprisals is never ending. The centuries-old inertia behind these animosities, moreover, defies resolution. The seeming implication is that Africa’s complicated ethnic diversity leaves the continent perpetually vulnerable to devastating internecine conflict. This, in turn, cripples prospects for sustained economic progress and democratization.

Ethnicity, Ethnic Mobilization, and Conflict

In fact, ethnicity is typically not the driving force of African conflicts but a lever used by politicians to mobilize supporters in pursuit of power, wealth, and resources. While the ethnic group is the predominant means of social identity formation in Africa, most ethnic groups in Africa coexist peacefully with high degrees of mixing through interethnic marriage, economic partnerships, and shared values. Indeed, if they did not, nearly every village and province in Africa would be a cauldron of conflict.

Ethnicity became an issue in Kenya’s recent elections because of a political power struggle that found it useful to fan passions to mobilize support. It was not an autonomous driver of this post-electoral violence, however. While Daniel arap Moi’s 25 years in power governing through an ethnic minority–based patronage network did imprint group identity on Kenyan politics, there are many instances of crossgroup cooperation. Most prominent of these were the formation of the Kenya African National Union by the Kikuyus and Luos in the 1960s to fight for independence and the creation of the National Rainbow Coalition to break the one-party stranglehold on power in 2002. Intergroup cooperation, in fact, is the norm rather than the exception. Intermarriage is common, and many of Kenya’s youth, especially in urban areas, grew up identifying as Kenyans first, followed by ethnic affiliation. This is not to suggest that ethnically based tensions do not persist—rather, that the post-election bloodshed in 2007–2008 was not an inevitable outburst of sectarian hatred.

“Misdiagnosis of African conflicts as ethnic ignores the political nature of the issues of contention.”

In Rwanda, Hutus and Tutsis have intermarried to such an extent that they are often not easily distinguished physically. They speak the same language and share the same faith. Indeed, ethnic identity was closely associated with occupation (farmer or herder) and one’s identification could change over time if one shifted occupation. Violence in Rwanda has usually been over resources and power. Political manipulation of these resource conflicts led to the well-orchestrated 1994 genocide. Politicians, demagogues, and the media used ethnicity as a play for popular support and as a means of eliminating political opponents (both Tutsis and moderate Hutus).

In Ghana, the military government of General I.K. Acheampong decided in 1979 to vest all lands in the northern region in 4 of the 17 indigenous ethnic groups that lived in this area. At the time, the military was seeking an endorsement of one-party government. Since the proposal was subject to a national referendum, the government needed a “Yes” vote from the north to counter a “No” vote from the south. The land arrangement was the deal some northern politicians cut with the government for their support. The issue became a defining moment in the mobilization of ethnic groups such as the Konkomba and Vagla in the name of developing their area. The first intercommunal violence began shortly thereafter—and continued for the next 15 years, culminating in the Guinea Fowl War of 1994–1995 in which some 2,000 people were killed. During that time, more than 26 intercommunal conflicts over land (resources) and chieftaincy (power) occurred in northern Ghana—all characterized as ethnic conflicts.

Such a classification—in Ghana as in many other African conflicts—is an oversimplification. Indeed, many conflict scholars find the ethnic distinction baseless.1 Often it is the politicization of ethnicity and not ethnicity per se that stokes the attitudes of perceived injustice, lack of recognition, and exclusion that are the source of conflict. The misdiagnosis of African conflicts as ethnic ignores the political nature of the issues of contention. People do not kill each other because of ethnic differences; they kill each other when these differences are promoted as the barrier to advancement and opportunity. The susceptibility of some African societies to this manipulation by opportunistic politicians, it should be noted, underscores the fragility of the nationbuilding enterprise on the continent.

In many cases, the political choices made by states lay the foundation for ethnic mobilization. In other words, “ethnic conflicts” often emerge in multiethnic, underdeveloped societies when the behavior of the state is perceived as dominated by a particular group or community within it, when communities feel threatened with marginalization, or when no recourse for redressing grievances exists.2 Ethnic thinking and mobilization generally emerge from the resulting inequitable access to power and resources and not from an intrinsic hatred.

Periodic eruptions of violence involving Christians and Muslims in Nigeria’s highly diverse “middle-belt” Plateau State capital, Jos, are a case in point. This violence is usually reported as “communal conflict.” This characterization, however, overlooks some of the institutional arrangements of Nigeria’s federal system that foster this violence. State and local governments have enormous influence in this system, controlling roughly 80 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.3 In addition to the implications for resource allocation, local governments are responsible for classifying citizens as “indigenes” or “settlers.” Settlers are banned from holding some positions in state government, are not eligible for state education subsidies, and are restricted from owning land. In Plateau State, this translates into Hausa-speaking Muslims being classified as settlers even if their families have lived in the region for generations. The ongoing and at times violent tensions resulting from such an arrangement are predictable.

Institutional Constraints to Ethnic Mobilization

Recognizing that ethnicity is a tool and not the driver of intergroup conflict should refocus our attention to the political triggers of conflict. That there is a mobilization stage in the lead-up to conflict, moreover, highlights the value of early interventions before ethnic passions are inflamed.

State institutions and structures that reflect ethnic diversity and respect for minority rights, power-sharing, and checks and balances reduce the perception of injustice and insecurity that facilitates ethnic mobilization. The justice system is key. In societies where justice cannot be obtained through public institutions, groups are more likely to resort to violence for resolving their grievances. A just society is more than the legal system, however. A genuine separation of powers and the rule of law are needed to prevent abuses of state power. Such measures prevent state functionaries from using their powers to benefit their ethnic groups to the detriment of other groups. In much of Africa, the executive rather than the legislative branch determines most land policies. Invariably, the ethnic group of the president benefits from these policies. In Kenya, Kikuyus used the political and economic leverage available to them during Kenyatta’s regime to form land-buying companies that facilitated the settlement of hundreds of thousands of Kikuyus in the Rift Valley during the 1960s and 1970s.4

An even-handed legal system also creates space for civil society organizations to coalesce around issues of common concern, such as development, accountability, and human rights transcending ethnic affiliations. This, in turn, facilitates exchanges between groups. Business associations, trade and professional associations, sports clubs, and artist groups, among others, are all civil society organizations that can cut across ethnic lines and engage government in productive ways.

Electoral systems and elections constitute another area of policy focus. Elections on their own do not necessarily lay the foundation for stability. On the contrary, they can be a source of ethnic tensions and violence. The practice of winner-takes-all electoral outcomes in a multiethnic and underdeveloped state where the government controls the bulk of resources in a society makes winning an election a life-and-death issue. Accordingly, it is important that electoral systems are independent of political control. One of the differences between Kenya’s and Ghana’s recent elections was the independence and resilience of the Ghanaian electoral commission. Furthermore, once the Electoral Commission in Ghana has validated electoral results, private groups then have the right to challenge irregularities in the courts. These multiple levels of accountability gave Ghanaians confidence in their electoral system despite a very close 2008 election.

“Diversity in the security sector also has tangible benefits as ethnically representative police forces are linked with lower levels of conflict.”

Ghana’s Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ) provides another useful institutional mechanism for mitigating ethnic conflict. Backed by a constitutional act (Act 456), CHRAJ was mandated in 1993 to “investigate complaints of violations of fundamental rights and freedoms in both public and private sectors, investigate complaints of administrative injustice, abuse of power and unfair treatment of any person by a public officer in the exercise of official duties.” The commission was also mandated to “educate the public on their fundamental rights and freedoms and their responsibilities towards each other.” For the first time, Ghanaians could take government to task and have their grievances addressed immediately at the local level. Coming out of 12 years of military rule and entering a new democratic dispensation, the formation of the commission was timely. Apart from the constitutional mandate, funding was committed to support CHRAJ offices at the national, regional, and district levels. The fact that the commissioner was independent of executive influence gave the commission enormous credibility. It is also what distinguishes the CHRAJ from similar commissions in other countries. Since its inception, the commission has handled high-profile cases involving government ministers, unlawful dismissals involving the Inspector General of Police, and the confiscation of people’s assets. In each of these high-profile cases, the court ruled in favor of the commission.

Religious bodies and local nongovernmental organizations have disseminated CHRAJ messages to the grassroots through workshops, seminars, and support for communities with grievances to present their case to the commission. With this infrastructure, education, and resources in place, Ghanaians have come to appreciate the value of the rule of law and the timely response to their grievances at the community, district, and regional levels.

Priorities for Mitigating Ethnic Conflict in Africa

Reframing ethnic conflicts as political competitions for power and resources should shift how we think about mitigation strategies. Rather than accepting identity conflict as an inevitable feature of Africa’s highly diverse ethnic landscape, a number of preventative policy interventions can be pursued.

Build Unifying Institutional Structures

At the core of ethnic conflicts is the relationship between ethnic groups and the state in the search for security, identity, and recognition. How the state negotiates these interests and needs will determine the level of identity conflicts. A comprehensive legal system that respects minority rights, protects minorities from the abuse of state power, and ensures that their grievances are taken seriously will reduce opportunities for ethnic mobilization. Among other things, this requires equitable access to civil service jobs and the various services the state provides. Key among these state functions is minority participation within the leadership and ranks of the security sector. The military can be a unifying institution, creating bonds between ethnic groups, helping to forge a national identity for all ethnicities, providing youth an opportunity to travel and live throughout the nation, and allowing minorities to advance to positions of leadership through merit. Diversity in the security sector also has tangible benefits as ethnically representative police forces are linked with lower levels of conflict in diverse societies.5

Elections are another flashpoint of ethnic grievances—and therefore a priority for mitigating violence. Elections present clear opportunities for politicians to play on ethnic differences. Establishing an independent, representative electoral commission led by individuals with impeccable integrity can circumscribe these ploys. As seen in Ghana and elsewhere, the effectiveness of a competent electoral commission can make an enormous difference in averting ethnic violence. Independent electoral commissions can also establish electoral rules that reward candidates for building cross-regional and intergroup coalitions—and indeed require them to do so. Ensuring electoral jurisdictions do not coincide with ethnic boundaries is one component of such a strategy.

Ghana’s experience with the CHRAJ provides further lessons for institutional responses to mitigate ethnic tension. The CHRAJ provided an accessible government entity responsible for documenting and reconciling ethnic grievances. Creating variants of the CHRAJ in other African countries would thus be a point of first contact for minority groups who believe that they have been aggrieved. Such a human rights commission would then be empowered to serve as something of an ombudsman for investigating and remedying intergroup conflicts at the local level. It would be granted access and convening authority to draw on the assets of all other government entities that may have a role in resolving the grievance. In this way, the human rights ombudsman would be an official mechanism to which individuals and communities could proactively go to resolve intergroup differences. Given the nature of its work and the requirement to gain the trust and support of local populations, representatives of the human rights ombudsman would need to be accessible at the local level in all potentially volatile regions of a country.

Reinforcing Positive Social Norms

Over the medium to long term, defusing the potency of ethnicity for political ends requires reorienting cultural norms. Social marketing campaigns that promote national unity, intergroup cooperation, and “strength through diversity” themes can help frame the ethnic narrative in a positive light, thereby making it more difficult for divisive politicians to play on differences to mobilize support. Such a communications strategy would be complemented by a country-wide, community-level outreach campaign implemented by civil society organizations that targets youth reinforcing messages of “one country, one people,” tolerance for other groups, and nonviolent conflict resolution.

Targeting youth is particularly important for breaking intergenerational attitudes regarding ethnicity. Youth is the population group most easily mobilized to violence. A comprehensive and deliberate educational system designed to promote integration and coexistence with emphasis on civic lessons on citizenship and what it means to be a nation will foster this concept of a common people with a common destiny. A social marketing campaign also brings this unifying message directly to the people rather than relying on ethnic or political leaders (who may be benefiting from the perceived divisions). This campaign, paralleling the successful efforts of legendary Tanzanian leader Julius Nyerere, would simultaneously help build a common national identity (which so many African countries still lack) while taking the ethnicity card off the table for political actors.

Complementing efforts to shift cultural and political norms surrounding identity, sanctions need to be created and applied to those actors who continue to attempt to exploit ethnic differences toward divisive ends. Two groups are critical here: the media and politicians. Penalties would take the form of a national law criminalizing the incitement of ethnic differences by political actors and public officials. These laws then need to be enforced. An independent body, whether the electoral commission or a human rights council along the lines of Ghana’s CHRAJ, would be given responsibility for investigating charges of ethnic incitement—and the authority to assess penalties including fines and bans from holding public office. The symbolism generated from a few highly publicized cases would go far toward shifting these norms.

The media also play a unique role in communicating information and impressions in society. As such, they have an indispensable function in a democracy to foster dialogue and debate. Unfortunately, in practice, it is common in Africa for certain media outlets to be controlled by politically influential individuals who are willing to whip up identity divisions to support their interests—greatly elevating the potential for ethnic conflict. Media also have the potential to escalate a local conflict to the national level—raising the stakes for violence as well as complicating the task of resolution. Given the unique potential that media have for shaping social attitudes and mass mobilization, most societies accept that media must meet certain standards for responsible behavior. These standards should include prohibitions against programming that incites ethnically based animosity. Again, independent monitoring bodies, possibly in collaboration with national media consortia, should be given the authority to quickly investigate and enact tough sanctions against outlets deemed to have violated these standards against hate mongering.

Early Response

A key lesson learned from experience in preventing and quelling ethnic tensions in Africa is the value of addressing these issues sooner rather than later. Tamping down these tensions is more feasible—and less costly in social and financial terms—if it occurs before intergroup divisions have been mobilized and violence ensues (which, in turn, sets off a new and more polarized cycle of grievance, fear, distrust, and retaliation). It also underscores the importance of government officials taking every expressed struggle by groups seriously (for example, claims of discrimination, denigration, or denial of rights) and responding immediately. This, of course, presupposes that the government is competent and willing to deal with these conflicts and is not a party to the grievance in the first place. The creation of a human rights ombudsman that is seen as an impartial actor that will document and investigate ethnically based claims provides the dual benefit of a mechanism that addresses these claims fairly and can help defuse tensions before they boil over. Belief that there is a systematic means by which one’s grievances can be fairly addressed reduces the likelihood that individuals will feel the need to take corrective measures into their own hands.

Finally, preventing ethnic tensions from escalating out of control requires a rapid response capacity within the security sector to respond when intergroup clashes occur. These police and military forces must be trained to respond in an even-handed yet assertive manner that builds confidence in the state’s capacity to intervene constructively. As most ethnic violence occurs at a local level—along a faultline bordering neighboring communities—the value of a rapid response before other triggers are tripped is vital. The local nature of these ethnic triggers also points to the need for broad-based training of the security forces. Every local police jurisdiction needs to have the awareness and capacity to respond in such ethnically charged contexts as they will likely be the first responders. They, in turn, can be backed up by military forces (most likely from a provincial level) that will, in most cases, have better transport, communications, and firepower to bring a situation under control. However, the initial response by the police is critical in shaping the trajectory of that confrontation.

There is a human tendency to reinforce intergroup differences. Civilized societies learn ways to prevent these impulses from becoming polarized and turning violent. Understanding the political roots of many of Africa’s ethnic clashes can help us focus and redirect our conflict prevention efforts—and in the process enhance the effectiveness of our growing toolkit of corrective measures.

Notes

- ⇑ Bruce Gilley, “Against the Concept of Ethnic Conflict,” Third World Quarterly 25, no. 6 (2004).

- ⇑ Edward E. Azar and Robert F. Haddad, “Lebanon: An Anomalous Conflict?” Third World Quarterly 8, no. 4 (1986).

- ⇑ Philip Ostien, “Jonah Jang and the Jasawa: Ethno-Religious Conflict in Jos, Nigeria,” Muslim-Christian Relations in Africa, Sharia in Africa Research Project, August 2009.

- ⇑ Walter Oyugi, “Politicized Ethnic Conflict in Kenya: A Periodic Phenomenon,” Government of Kenya, 2002.

- ⇑ Nicholas Sambanis, “Preventing violent civil conflict: The scope and limits of government action,” 2002, background paper for the World Development Report 2003: Dynamic Development in a Sustainable World (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2003).

Father Clement Mweyang Aapengnuo is a Doctoral Student in the Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University. He is the former Director of the Center for Conflict Transformation and Peace Studies in Damongo, Ghana.