Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

The growing share of Africa’s urban residents living in slums is creating a further source of fragility. In response, some cities are implementing integrated urban development strategies that link local government, police, the private sector, and youth to strengthen social cohesion and enhance stability.

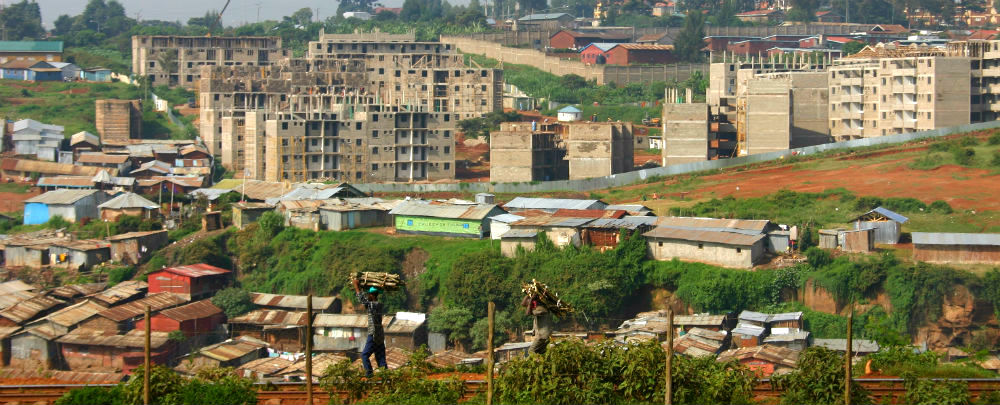

Kibera slum in Nairobi, Kenya, with condos under construction in the background. (Photo: klndonnelly)

Highlights

- The share of Africa’s urban residents living in slums is steadily rising, an outgrowth of the continent’s rapidly expanding population. Meanwhile, residents of African cities report among the highest levels of fear of violence in the world.

- The inability of government institutions to resolve or at least mitigate conflicts over land, property rights, and services for urban residents, coupled with either absent or heavy-handed responses of security agencies in African slums, is contributing to a growing mistrust of African security and justice institutions.

- Integrated urban development strategies—involving local government, police, justice institutions, the private sector, and youth—are necessary to build trust and adapt policies that strengthen economic opportunities, social cohesion, and security in Africa’s cities.

In November 2016, the Lagos State Government carried out a violent demolition of the Otodo Gbame urban slum in the heart of Lagos. Government forces showed up with sledgehammers and bulldozers. They lobbed teargas canisters and opened fire on protesters. Several dozen residents were killed and 30,000 were left homeless. Many lost the few assets they owned. Lagos State authorities defended the demolitions calling the community a “ticking time bomb, an environmental hazard, and a den of armed robbers.”1

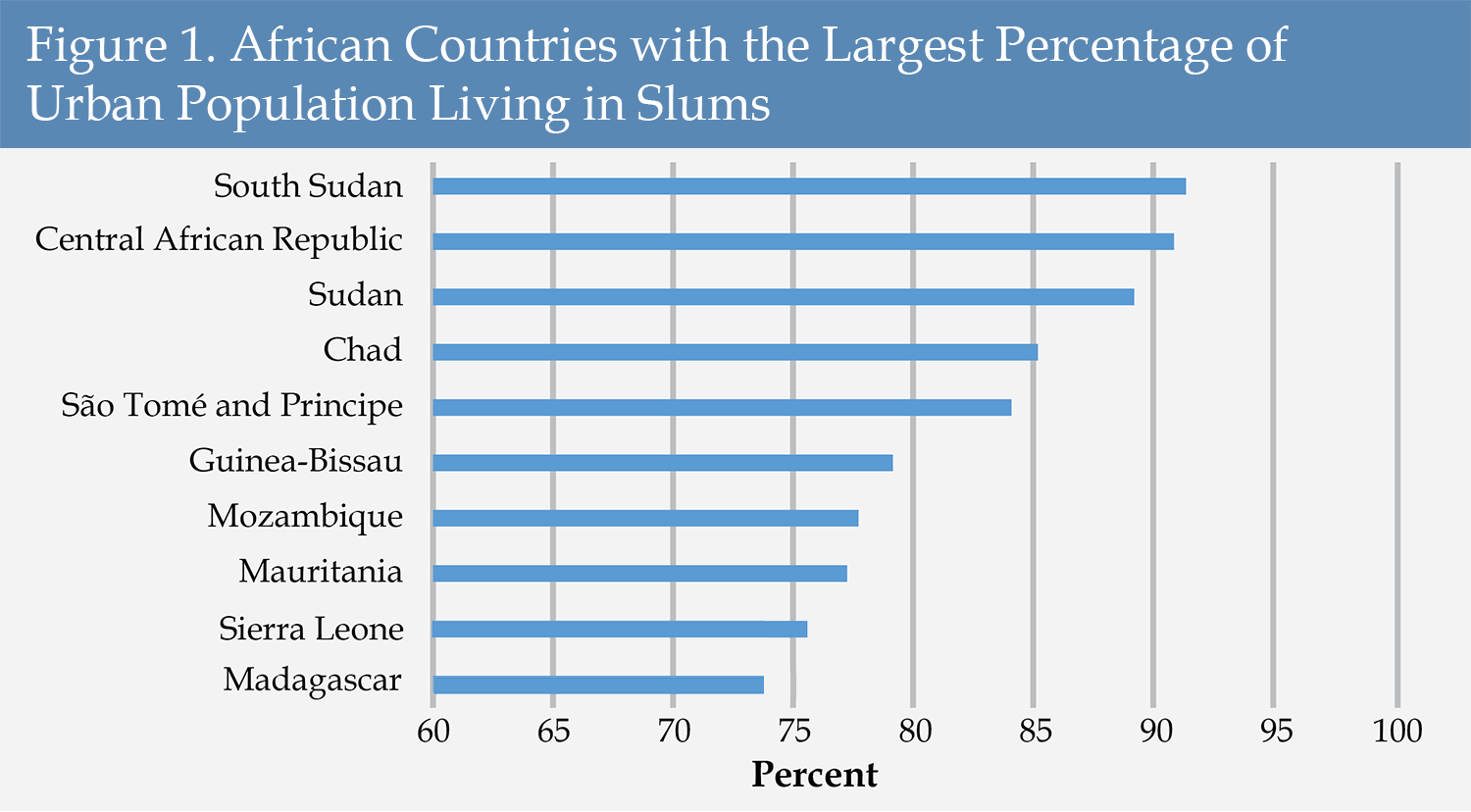

Such altercations between government authorities and urban residents in Africa are playing out increasingly regularly. African cities are growing by an estimated 22 million people annually and are on pace to double over the next 25 years. Lacking other options, many who migrate into Africa’s cities are moving into unplanned settlements. In Nairobi, for example, almost 70 percent of the total population live in unplanned settlements clustered in about 5 percent of the city’s residential area.2 Yet, Kenya does not even factor into the top 10 African countries with the largest percentage of urban residents living in slums (see Figure 1).

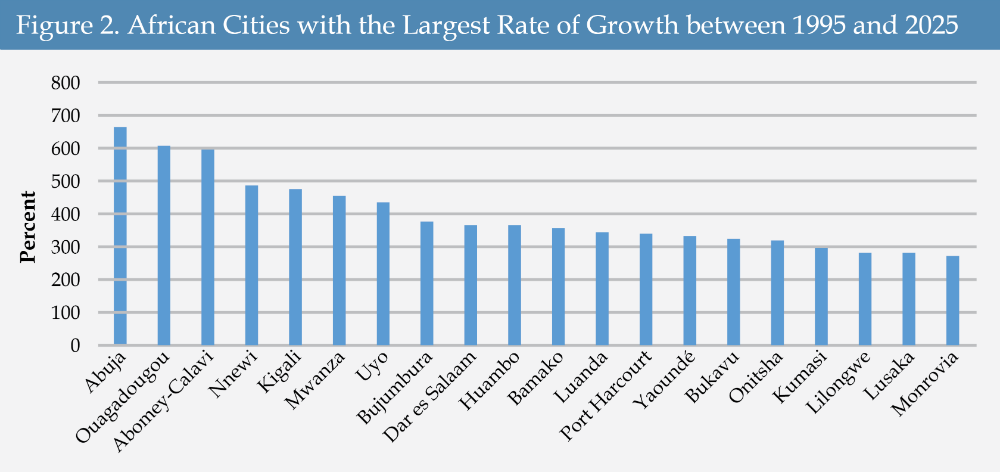

The rapid pace of urbanization is transforming the challenges African cities face to provide services, promote employment, and ensure basic security (see Figure 2). In many African countries, violence correlates with the unplanned and underdeveloped sections of these cities.3 This pattern of urban fragility can threaten the national political equilibrium.

Revealingly, Africans report among the highest levels of fear for safety of any region in the world when just urban areas are taken into consideration. Levels of fear for safety in rural areas are significantly lower.4 This highlights the urban face of crime and violence in Africa. Around 40 percent of Africans living in urban areas report feeling unsafe walking in their own neighborhoods.5 Many urban residents express vulnerability due to lack of land or property rights, makeshift housing, and unplanned or insufficient infrastructure to support the growing communities of people living in informal settlements.

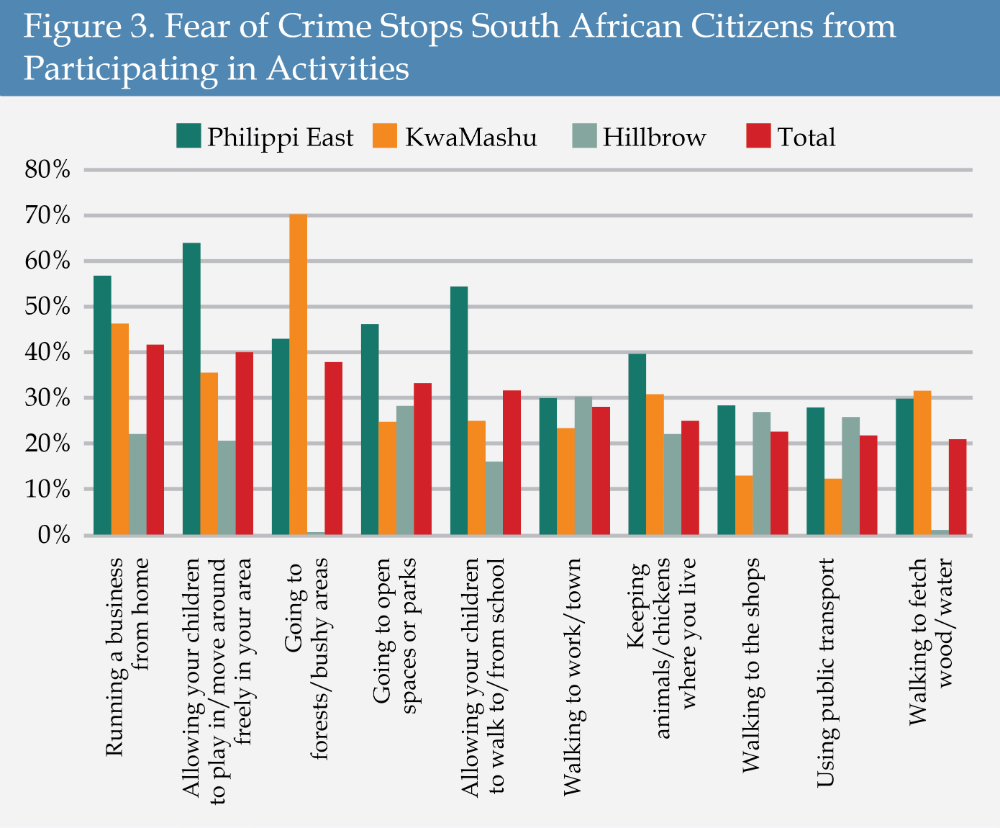

These fears have direct social and economic implications. Surveys conducted with 750 South Africans in “hot spot” (or high crime) neighborhoods of Cape Town (Philippi East), Durban (KwaMashu), and Johannesburg (Hillbrow), reveal fear of being a crime victim stopped residents from participating in activities ranging from running a business from home, to allowing children to walk to and from school, to going to public places or parks, to using public transit, to walking to get food and water (see Figure 3).6

Source: South African Cities Network7

New forms of conflict and exclusion may arise in densely populated and underserved urban centers. For example, “[x]enophobic hostility towards other ethnic groups, ‘foreigners’, … and socio-economic struggles around issues of land and services [can] emerge.”8 This form of fragility manifests through a weak sense of shared identity, ethnic fragmentation, a sense of exclusion, and the absence of social cohesion. A form of “violent cultural trauma” describes the loss or disintegration of cultural beliefs and values as new social patterns begin to emerge.9 Each of these factors pose deep challenges to social stability.

Urban fragility constitutes a significant threat to the political stability and economic well-being of African countries.10 Managing the urbanization processes and positioning cities as stable political and economic centers is an urgent security priority for African governments.

Trust, Justice, and Violence

Central to the connections between insecurity and political fragility in cities is the interplay of unplanned growth, low levels of trust in security sector institutions, the youth bulge (with pressures on livelihoods and public spaces), and the emergence of ungoverned spaces (i.e., controlled by nonstate actors, including criminal networks). The inability of state institutions to mitigate and resolve conflicts over land, services, and livelihoods is a major contributing factor to urban violence. This, in turn, spurs the creation of vigilante organizations and the imposition of street justice as various groups seek to either protect or enforce their self-interests.11 Distrust is heightened when security forces use heavy-handed means, such as razing homes, in response to urban instability. Such actions further weaken the ability of public institutions to maintain order.

In surveys conducted by Afrobarometer, more than half of crime victims did not contact the police because, among other things, they feared being asked for a bribe or being dismissed out of hand.12 Moreover, 54 percent of respondents said that getting assistance from a court was “difficult” or “very difficult,” and 30 percent reported paying a bribe for assistance.13 In addition, 43 percent reported not trusting courts or trusting them just a little, while 60 percent experienced lengthy delays in court cases.14 Poor people were the least likely to trust the court system. Young people were often the target of harsh policing, which was worsened by a widespread lack of facilities or procedures for juvenile justice.

A World Bank study on urban fragility in Africa used the experiences of Nigeria, South Sudan, and the Republic of the Congo to highlight how inequality, alienation and disaffection, and lack of educational opportunities—especially among young men—leads to higher levels of crime and violence.15 It found that:

In many fragile states, “systems of law and order, ranging from the police, judiciary, penal systems and other forms of legal enforcement, are dysfunctional and considered illegitimate by the citizens who they are intended to serve.” Per consequence, “capacity gaps in providing basic and accountable security services is a key determinant shaping urban violence.”16

Justice systems play a central role in providing both legitimate processes for the resolution of grievances that might otherwise lead to conflict and disincentives for crime and violence. In unplanned settlements, a major challenge for citizens is land tenure rights and access to courts for resolving ensuing disputes. Similarly, accessing government services for registering businesses, recording births and deaths, and obtaining identity cards that are required for accessing other services—such as health care or schools—can contribute to a lack of trust and underreliance on formal government institutions.

Kibera slum in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo: Trocaire)

In Nairobi’s slums, a legal needs assessment conducted by the NGO Microjustice4All found such lack of access, particularly for women and children. It therefore created a “toolkit with information on birth certificates, cohabitation contracts, inheritance proceedings, land and housing registration, registration of women’s businesses, access to microfinance, and social benefits.”17 The success of the program led to its expansion to six “outlets” in additional slum areas of Nairobi. Over an 18-month period, it conducted 5,322 consults, 468 cases, directly assisted 3,921 persons, and held 25 events that reached 2,466 people.18 This type of outreach allows families to more easily access the services available and, in the process, gain trust in the institutions intended to serve these communities.

In general, governments have not given adequate attention to issues around corruption, criminal justice, and community policing. Yet corruption significantly undermines citizens’ trust in political arrangements and reduces citizen willingness to engage with formal policing and justice systems. Perceived corruption in the security and justice sectors has a particularly debilitating effect on public trust. Violent crime and conflict in such contexts are more likely.19 Corruption also creates more room for vigilante justice and can encourage the formation of informal militias to carry out enforcement of “justice” from the street.

Youth Bulge

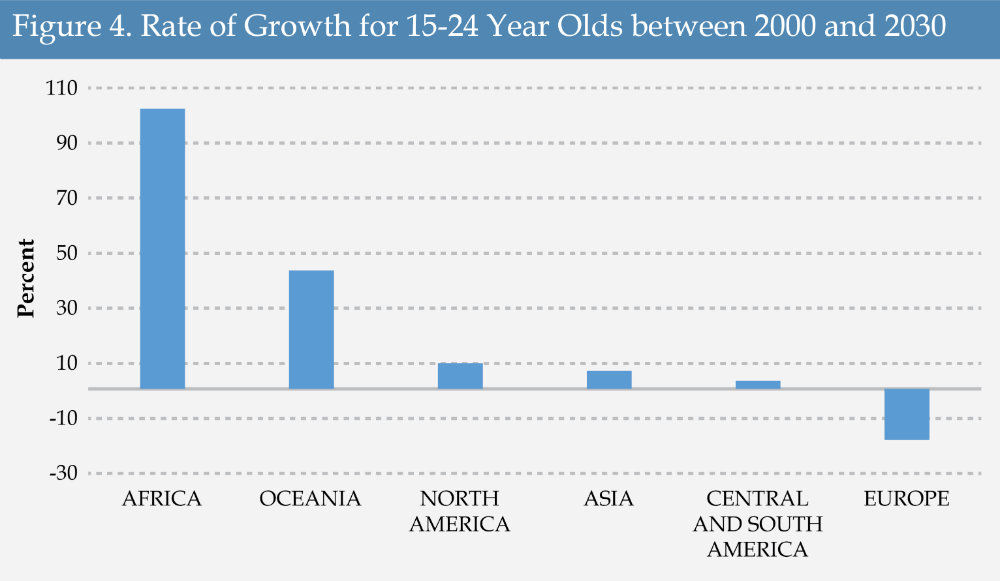

Africa is expected to see an increase of 174 million youth (15-24 year olds) between 2000 and 2030, a rate of growth that far exceeds that of any other region (see Figure 4). Not only do young people account for about 20 percent of the population, they represent 40 percent of the workforce and 60 percent of the unemployed.20 The rapid pace of urbanization, combined with the relatively youthful age of African urban populations, limited access to education, and high proportion of young people with few job prospects, presents a major risk factor for political stability. A key problem is that many governments see young people as threats rather than as opportunities.

The need to belong and find identity draws young men to gangs, criminal networks, extremist groups, and vigilantism. Indeed, youth find identity in such groups, particularly when faced with economic inequality and unemployment. In Kenya, community-based armed groups take three different forms: vigilantes, militias, and gangs. None of these are static and all have some degree of legitimacy in the eyes of parts of the communities in which they operate. So while any of these groups can at times provide security to parts of communities—and at times they even act like a formal security provider since they might collect “taxes” from individuals or businesses for their services—that practice can easily become perceived as extortion. While some groups rightfully turn over potential criminals to the police, others engage in egregious human rights abuses when they feel justice is not sufficiently swift.21

Integration

Efforts to foster stability in Africa’s rapidly evolving urban landscape have emphasized an integrated approach based on reducing insecurity while promoting greater well-being for urban residents. Basic foundations for this approach focus on effective policing, a competent and honest judiciary, and the inclusion of youth in planning processes as a central means for building confidence in public institutions and reducing fragility. Under such an integrated framework, citizens are protected by security forces that respect their rights, and urban residents can access legitimate dispute resolution mechanisms. Meanwhile, other causes of fragility—such as lack of access to education, basic government services, clean water and sanitation, and employment—must be addressed as part of a complementary effort to create sustainable, stable urban areas.

Abidjan’s Treichville: Lessons from Community-based Efforts and Social Cohesion

In the late 1990s, one of Abidjan’s municipalities, Treichville, adopted a strategy to ensure that the entire community had a role in maintaining urban safety. The longstanding mayor, François Albert Amichia, promoted a theory of social cohesion and unity for development. Mayor Amichia argued that viewing yourself and your neighbors as integral to mutual security would lay the groundwork for development. In 1996, the municipal council created a surveillance brigade, the Treichville Sécurité Vigilance, whose members were recruited from violent areas, thereby giving community members responsibility for their own safety. The brigade employed young people, and petty crime decreased.

In 1998, Ivoirian mayors formed le Forum Ivoirien pour la Sécurité Urbaine (the Ivoirian Forum for Urban Security) and implemented a violence prevention project by each creating a comité communal de sécurité (communal security committee or CCS). Each CCS is multisectoral and includes the mayor, city officials, traditional leaders, school officials, the private sector, and representatives from religious organizations and associations for youth, women, and the elderly. The CCSs have periodic meetings to discuss how to reduce urban violence, build capacity, organize activities for at-risk groups, and provide an opportunity for stakeholders to share concerns.

During the 2010 electoral crisis, the CCSs reportedly played a key role in mediating conflict in Treichville by identifying individuals suspected of inciting violence and using the community cohesion theory Mayor Amichia had developed to defuse tensions.22 As a result, while most had expected highly diverse Treichville to suffer deadly violence in the wake of the contested presidential poll, the area in fact remained calm. The Mayor credited the city’s work on social cohesion and community security for this outcome.

South Africa’s initial efforts to adopt an integrated approach to urban fragility began in 1996 with the adoption of a National Crime Prevention Strategy. In 1998, the South African government issued a White Paper on Safety and Security. Almost immediately, cities such as Johannesburg began creating Community Policing Forums (CPFs) to implement the strategy at the community level. The CPFs, which the South African Police Service endeavored to establish at each police precinct, aimed to create a mechanism to increase communication, build trust, improve police services to the community, and promote joint problem identification within communities. A key lesson from the CPFs, however, was that their focus on crime prevention failed to address other drivers of urban fragility and their links to deficiencies in governance.

“A key lesson from the CPFs … was that their focus on crime prevention failed to address other drivers of urban fragility and their links to deficiencies in governance.”

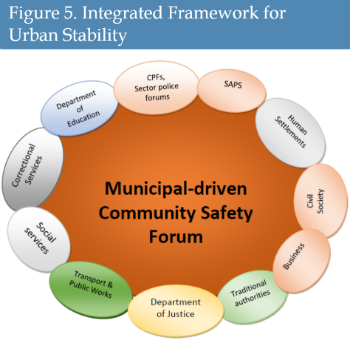

As part of an effort to address these challenges, communities began creating Community Safety Forums (CSFs). The establishment of CSFs was intended to “promote the development of a community where citizens live in a safe environment and have access to high quality services at [the] local level, through an integrated multi-agency collaboration between organs of state and various communities.”23 Upon their establishment (and periodically thereafter) CSFs conduct “safety audits” within communities and develop “community safety plans.” They then work to implement the plan and provide an annual report on their progress to the municipality and the province. There is no set standard for such plans because they depend on participants for elaboration and are constrained by each municipality’s resources in terms of implementation. Yet, effective CSFs inform municipal leadership on means to enhance urban safety beyond community policing. Community safety plans are then included in integrated development plans at the municipal level (see Figure 5).

Source: Mumba Development Services.24

Sedibeng District Municipality in Gauteng Province created an Intersectoral Forum on Safety and Security in 2004. At the time, officials observed that soaring crime rates were driving businesses, their clients, employees, and residents out of the District. Renamed a CSF in 2006, the Sedibeng Community Safety Forum holds regular meetings with government departments, business, schools, churches, and the wider community to share information, identify possible crime generators and maximize scarce resources through collaboration.

Since its creation, the Sedibeng CSF has contributed to the establishment of social crime prevention units at the district level as well as contributed to the installation of closed-circuit television systems across the region, all of which caused a significant decrease in violent crimes in the Vereeniging Central Business District. For this, it received recognition under the Best Community Corrections Category in 2011.25 In short, community involvement in an integrated approach to security and safety contributed to increased security, improved service delivery, and economic development.

From Urban Fragility to Urban Security

Integration

Security and reduction of urban fragility are a much wider challenge than increasing police presence or responding to violence. They require coordinating all services through inclusive planning and attention to governance across the city. Governments, donors, and communities need to recognize urban fragility and insecurity as a set of development problems that can increase the short-term and medium-term risks of conflict. Policing, criminal justice, and security sector reform, therefore, should be approached as part of a wider governance strategy to provide security to urban residents while building trust and cooperation. Making the reduction of fragility part of urban planning and development recognizes that not only are violence, crime, fear, and insecurity detrimental for local communities, but they are also major inhibitors of economic growth and investment.

Integrated urban policies increase the trust between citizens and urban officials. Together, communities and governments design urban plans that are flexible in the face of continued in-migration and local insecurity. With this type of governance, increased trust, as reflected in access to basic services—including access to a fair judicial system—and respect for the role and authority of legitimate police, contributes to urban security. An integrated approach to building secure communities should be embedded in governmental policies, strategies, and programs with the aim of their effective implementation at the local level.

A fundamental challenge to planning in Africa’s rapidly evolving municipalities is often the absence of basic information about certain communities. This makes the development of appropriate and adequate policy responses very difficult. Cities have used new technologies, in addition to surveys and related tools, to develop comprehensive profiles of the causes and drivers of fragility and insecurity. The urban profile of Treichville created by UN-Habitat provides a useful example of how a comprehensive map can be developed. It examined the municipality’s governance structures, its finances, available land and tenure arrangements, the presence of slums, environmental aspects and means for managing disasters, the city’s economic situation, the existence and quality of basic urban services, the level of security, and what cultural resources the city had that could draw in visitors and boost revenue.26

Using Simple Web Platforms to Help Communities Build Maps

The absence of maps (including the placement of dwellings and businesses) and accurate census data prevents many African cities from building needed infrastructure (e.g., paved roads, clean water and sewage systems, and cell phone towers) or planning for the construction of needed schools, health care facilities, police stations, and public transit systems.27 Because many of the poorest and most fragile communities have not been mapped, the NGO Humanitarian Open Street Map Team (HOT) works with these communities around the world to create such resources. Such collaboration brings citizens, governments, NGOs, and donors together to better determine the needs of these communities and the policies necessary to help them.28

In Liberia, for example, HOT has worked in several cities to map neighborhoods, including the identification of access to infrastructure such as water points and health services. In Uganda, HOT has worked with university students and community members to map access to financial services, including mobile money agents. In the past, such data was collected through periodic and expensive national surveys, missing many inaccessible neighborhoods. This program uses Twitter and the simple web platform Open Street Map, allowing anyone to add data and use it for free. HOT conducts free training sessions for communities to use their cell phones to contribute to such maps.

Trust

Improvements in security begin with greater public trust. This occurs, in part, through the delivery of basic services and infrastructure as well as the presence and trustworthiness of government staff who are accessible to people on the street. Holding community-level forums to discuss issues and advocate open innovation is also needed, as is working with communities to identify needs and risks. Increased trust results when security forces improve their ability to maintain relations, particularly with underserved low-income households.

Restoring Trust through Actions and Community Partnerships: Lagos, Nigeria

Between 1999 and 2015, two successive governors worked to include all sectors of society—from state authorities to civil society and the private sector—to promote the development of the city of Lagos. Lagos State’s 2013 State Development Plan aims to make the city “Africa’s Model Megacity and Global, Economic and Financial Hub that is Safe, Secure, Functional and Productive.”29 The governors increased transparency and accountability in urban planning, involved civil society in land use and budget preparation, and worked with the private sector to establish a State Security Trust Fund that provides funding for safety improvements such as lighting, police patrol vehicles, and school security.30 The initiatives also sought to engage rather than criminalize street youth through programs bringing them into public service roles, which, while difficult, has resulted in increased levels of public trust, greater citizen engagement, and improved services.31

Policing and Justice

Improved policing should be part of a wider safety strategy. This entails various forms of community policing, cross-government approaches, stronger oversight through statutory bodies, and greater community participation.32 Improved policing also involves a focus on the composition and capacity of the police force, including the recruitment of officers (as well as more women officers), and ensuring political, ethnic, and religious diversity.33 Police should receive regular training and have ongoing engagement with community leaders and youth organizations to build trust and communication. Officers also require adequate communication and mobility resources as well as reasonable pay. Both police and citizens should be able to anonymously report corruption and requests for bribes, thereby also increasing trust.

Improving urban stability also requires promoting incentives for sustained judicial reform. Doing so would bring together various government sectors on a regular basis to provide further “glue” to strengthen an integrated approach to security. Providing improved access to the justice system and improving overall court management and performance are priorities. Particular consideration is needed for addressing the challenges of unplanned urban spaces, namely land tenure and property rights, as well as ensuring the efficiency of the administrative agencies that register birth and deaths and provide identification cards and documents required for access to health services or schools.

Participatory Budgeting in Yaoundé, Cameroon

In 2006, Cameroon’s largest city, Yaoundé, decided to test an approach for increased and sustained citizen involvement in municipal decision-making. The approach uses community participatory budget meetings allowing citizens to voice priorities for their neighborhoods. In turn, city officials share with residents what budgetary trade-offs any decision might entail. The process intends to be collaborative, transparent, and pro-poor. Since then, two of Yaoundé’s districts, II and VI, have maintained the practice.

In Yaoundé II, meetings routinely saw 350 residents participating in 2009, during its first phase. In, 2010, there were five times more participants (1,700). In 2011, an average of 11,330 residents participated in meetings. The increased attendance can be partially attributed to the fact that officials sent text messages to nearly 50,000 residents of Yaoundé II and VI, encouraging them to participate. In addition, NGOs also began to attend. Indeed, the number of NGOs involved rose from 17 in 2009 to 65 in 2011. These participatory processes remain vibrant. Yaoundé II and VI have reportedly seen real results in terms of “cleaning up” these districts and making them safer and more livable for residents.34

Youth

Youth-focused approaches are challenging because they often require working outside of formal school structures and other formal institutions. However, they are necessary to promote the engagement of young people in security. When governments start seeing young people as allies rather than as police targets, they can work with youth organizations to bring young people together. Community organizations and government agencies should approach young people around their interests, for instance in health, sports, civic engagement, training and education, community engagement, arts, and culture. A “second chance” approach is vital, for example, through youth centers and after-school programs. Programs should also aim to reach younger groups through recreational activities (as opposed to targeting older youth for skills development).35

Programs need to help youth connect with governments, likely through meetings with local leaders where youth issues and participation are raised and addressed. Such programs can also help address the challenges of the youth bulge through employment, civic engagement, and reforms in juvenile justice.

Addressing Youth Violence in Dakar and Promoting the Rights of Youth in Lusaka

In Senegal, l’Institut Africain de Gestion Urbaine (the African Institute for Urban Management) launched a project in 2017 to better understand and find effective means to address youth violence in Dakar. The project aims to:

- Diagnose the factors that cause youth exclusion and ensuing violence

- Help youth (both boys and girls) develop policies and strategies to address such exclusion and insecurity

- Facilitate the development of innovative platforms and solutions, designed by youth and using technology, to help youth secure the space they live in36

In Zambia, the World Justice Project supported an effort by Street Law Zambia to educate 400 middle schoolers (ages 11-14) in four schools in the slums of Lusaka on their legal rights when faced with police brutality and gender-based violence. Such programs help empower youth by providing them with strategies and resources to access security as well as play a role in their communities.

In several countries (e.g., Ghana, Liberia, Senegal), the Passport to Success program works to support urban youth in continuing their education so that they develop life and work-related competence. The programs have been specifically designed for vulnerable youth who are in school but at risk of dropping out, as well as those who are out of school, out of work, or working in dangerous environments. Program activities include workplace readiness skills, such as interviewing, respect for authority, and time management, along with tools for how to be a good employee. Participants receive assistance in developing a career plan. The program has been successful in increasing school retention (in Morocco there was a 44-percent decline in school dropout rates for youth who participated in the program) and employment opportunities.37

Conclusion

A context-specific, integrated approach that creates forums for local government, police, justice institutions, and youth to share perspectives and coordinate efforts can provide a means to pilot alternate approaches for reducing fragility and increasing security in Africa’s urban areas. Working with communities, these actors can strengthen the effectiveness of government agencies, contributing to a shift from urban fragility to urban stability.

Dr. Stephen Commins is Associate Director for Global Public Affairs and Lecturer in Urban Planning at the Luskin School of Public Affairs, University of California at Los Angeles. He has been an advisor on numerous World Bank, donor, and NGO initiatives on urban fragility.

Notes

- ⇑ Ogechi Ekeanyanwu, “Nigeria’s relentless real estate developers destroy entire slum,” TRT World, August 2, 2017.

- ⇑ Moritz Schuberth, “Hybrid security governance, post-election violence and the legitimacy of community-based armed groups in urban Kenya,” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 2 (2018), 388.

- ⇑ Clionadh Raleigh, “Urban Violence Patterns Across African States,” International Studies Review 17, no. 1 (2015), 90-106.

- ⇑ Ghassan Baliki, “Crime and Victimization,” Background Note for the World Development Report 2014: Risk and Opportunity (Berlin: German Institute for Economic Research, 2014).

- ⇑ Pauline M. Wambua, “Call the Police? Across Africa, Citizens Point to Police and Government Performance Issues on Crime,” Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 57 (Afrobarometer, 2015).

- ⇑ South African Cities Network, “The State of Urban Safety in South Africa Report 2017” (Johannesburg: SACN, 2017), 42.

- ⇑ Ibid.

- ⇑ Ussiasco Uscategui and Paula Andrea, “Urban Fragility and Violence in Africa: A Cross-Country Analysis” (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015), 6.

- ⇑ World Bank, “Invisible Wounds’: A Practitioners’ Dialogue on Improving Development Outcomes through Psychosocial Support,” Workshop Report (Washington DC, 2014), 10.

- ⇑ Stephen Commins, “Urban Fragility and Security in Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 12 (Washington, DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2011).

- ⇑ Oluwakemi Okenyodo, “Governance, Accountability, and Security in Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 31 (Washington DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2016).

- ⇑ Wambua, “Call the Police?” 7.

- ⇑ Carolyn Logan, “Ambitious SDG goal confronts challenging realities: Access to justice is still elusive for many Africans,” Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 39 (Afrobarometer, 2017), 18.

- ⇑ Ibid., 5, 20.

- ⇑ Uscategui and Andrea, “Urban Fragility and Violence in Africa,” 22.

- ⇑ Ibid., 2, citing Robert Muggah, “Researching the Urban Dilemma: Urbanization, Poverty and Violence” (Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, May 2012), 49.

- ⇑ “Microjustice Kenya: The Microjustice Toolkit for Women and Children in Nairobi Slums,” World Justice Project.

- ⇑ “Key Performance Indicators: Microjustice4All Country Programs per October 31, 2017,” Microjustice4All.

- ⇑ Institute for Economics & Peace, “Peace and Corruption 2015: Lowering Corruption – A Transformative Factor for Peace” (2015).

- ⇑ Julius Agbor, Olumide Taiwo, and Jessica Smith, “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Youth Bulge: A Demographic Dividend or Disaster?” in Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent in 2012 (Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 2012), 9.

- ⇑ Schuberth, “Hybrid security governance,” 386-404.

- ⇑ Anja Grob, Alex Papadovassiliakis, and Luciana Ribeiro Fadon Vicente, “Case Studies on Urban Safety and Peacebuilding: Lagos, Beirut, Mitrovica, Treichville and Johannesburg,” Technical Working Group on the Confluence of Urban Safety and Peacebuilding Practice Paper No. 19 (Geneva: Geneva Peacebuilding Platform, 2016), 9-11.

- ⇑ “Community Safety Forums Policy,” Government of South Africa Civilian Secretariat for Police, March 22, 2011, 13.

- ⇑ Mumba Development Services, “Capacity Building Process for Portfolio Councillors in Community Safety, Community Service in Cooperation between SALGA-DSL-GIZ-VCP partnership,” slide presentation prepared for the training program of the GIZ Inclusive Violence and Crime Prevention (VCP) Programme Building Skills for Safety Planning Project, November 15-16, 2016, 33, South African Local Government Association.

- ⇑ “Sedibeng Community Safety Strategy 2013-2017,” SaferSpaces.

- ⇑ UN-Habitat, “Côte d’Ivoire: Profil Urbain de Treichville,” Urban Profiles Series (Nairobi: UN-Habitat, 2012).

- ⇑ Steven Livingston, “Africa’s Information Revolution: Implications for Crime, Policing, and Citizen Security,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 5 (Washington DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2013).

- ⇑ Humanitarian Open Street Map Team (HOT) website.

- ⇑ “Lagos State Development 2012-2025,” Lagos State Government’s Ministry of Economic Planning and Budget, September 2013, 1.

- ⇑ Grob et al., “Case Studies on Urban Safety and Peacebuilding,” 2-5.

- ⇑ Diane de Gramont, “Governing Lagos: Unlocking the Politics of Reform,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (January 2015).

- ⇑ Sean Tait, Cheryl Frank, Irene Ndung’u, and Timothy Walker, eds., “The SARPCCO Code of Conduct: Taking stock and mapping out future action,” Workshop Report from the ISS Conference in Johannesburg, South Africa, March 16-17, 2011 (Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2011). See also, Simon Robins, “A Place for tradition in an effective criminal justice system: Customary justice in Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Zambia,” Policy Brief No. 17 (Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2009).

- ⇑ “Women Police Climb the Ranks in Africa,” UN Women, April 12, 2016.

- ⇑ Edward Paice, “The Booklovers, the Mayors, and the Citizens: Participatory Budgeting in Yaoundé, Cameroon,” Africa Research Institute (May 2014).

- ⇑ Matthew French, Sharika Bhattacharya, and Christina Olenik, “Youth Engagement in Development: Effective Approaches and Action-Oriented Recommendations for the Field” (Washington DC: USAID, 2014).

- ⇑ African Institute of Urban Management, “La violence chez les jeunes à Dakar : Contexte, facteurs et réponses,” Final Report from the Workshop for the Research Project on Youth Violence in Dakar, Senegal, May 10, 2017 (Dakar : International Development Research Centre, 2017).

- ⇑ “Passport to Success: Preparing Young People for the World of Work,” brochure, International Youth Foundation.