Download this Brief as a PDF ![]()

English | Français | Português

Summary

Nearly half of all uniformed peacekeepers are African and countries like Ghana, Rwanda, Senegal, and South Africa have provided troops to UN and AU missions almost continuously over the past decade. Despite such vast experience, African peacekeepers are often reliant on international partners for training before they can deploy on these missions. Institutionalizing a capacity-building model within African defense forces is a more sustainable approach that maintains a higher level of readiness to respond to emerging crises and contingencies on the continent.

Highlights

- Over 60,000 African troops from 39 different nations serve in peace operations worldwide.

- Maintaining African peacekeeping capability requires an ongoing training process to sustain the skill proficiency of troop contingents for rapid deployment and crisis response.

- Continued reliance on international trainers undercuts the institutionalization of African peacekeeping capability. An African-led training model would not only be more sustainable but would draw on the relevant, practical experience that African peacekeepers have gained over the years.

A state maintains a military to defend its borders, deter aggression, and fight and win its wars. These are missions normally associated with conventional force capabilities. Yet, many states are now more likely to call upon their militaries to conduct peace support operations than conventional combat operations. Over 100 countries provide uniformed personnel in support of 15 ongoing United Nations (UN) peace operations. Correspondingly, more and more nations train, resource, and equip their armed forces to achieve proficiency in the unique military skillset required for a peacekeeping environment. This is particularly true in Africa. Not only do 78 percent of all UN peacekeepers currently serve on the African continent, but nearly half of all uniformed peacekeepers are African. Over 60,000 uniformed personnel from 39 different African countries serve in peace operations worldwide. This preeminence of African nations among troop contributing countries (TCCs) to peace operations is understandable. Since most peace operations occur on the African continent, it is in African states’ regional security interests to participate, stabilize, and help shape a postconflict environment.

Participation in a peacekeeping operation (PKO) can also augment traditionally resource-constrained defense budgets. When a TCC deploys, the accompanying UN payment of per-soldier stipends, combined with reimbursement for contingent-owned equipment, provides the TCC with a significant financial supplement.1 For example, the provision of a standard 800-person battalion to a UN PKO can yield a TCC upwards of $7 million from the UN over the course of a 6-month rotation.2 Furthermore, external actors (i.e., Western nations) perceive a comparative advantage in offering training and equipment to African governments rather than deploying their own troops to a crisis area. Provision of training and equipment is not only viewed as a relatively low-cost endeavor to address an emergent or existing security crisis, but it likewise strengthens security cooperation relationships with African partners. Hence, there are shared interests among all parties in creating and enhancing the capability of African governments to conduct peace operations.

This intersection of mutually supporting interests has resulted in an abundance of programs, activities, exercises, and events all aimed at increasing peacekeeping capacity on the African continent. Denmark, France, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States are but a few of the many international donors that provide peacekeeping assistance to Africa. However, the tangible effects and long-term benefits of these efforts remain open to debate. While it is true that capability is often created or enhanced to address specific crises or missions, sustained capacity and operational readiness is short-lived. This is evidenced by the recurring cycle of donor-led training programs and the frequent inability of the African Union (AU) to rapidly respond to emerging crises despite their recurrence on the continent. This is a shortcoming that the AU has itself recognized. For example, an AU study of the 2012–2013 crisis in Mali lamented “Africa’s inability, despite its political commitment to Mali, to confront the emergency situation…and to respond adequately to the Malian government’s request for assistance. The only recourse was the French intervention to stop the offensive of the armed groups.”3 In short, the current manner and method of security assistance provided in support of PKOs does not appear to adequately or effectively advance the interests of any of the actors.

The Challenge of Retaining Readiness for Peace Operations

The standard model of donor peacekeeping assistance is often characterized as “train and equip” (T&E). A stereotypical T&E model consists of an African military pulling together a composite trainee cohort (a group that may or may not be the actual troop contingent that will deploy on an operation). The instructors providing the training are normally Western soldiers or, more often than not, private military contractors (PMCs) who teach from a standardized program of instruction. An equipment package is donated that may or may not be compatible or interoperable with the preexisting host nation’s inventory, spare parts, and maintenance systems. The result is a model that produces at best episodic and transitory proficiency.

While African states receive peace operations training assistance from various international partners, the United States is the predominant donor nation.4 From 2008 to 2012, the United States spent in excess of $1 billion in support of PKOs.5 For fiscal year 2014, the U.S. Department of State requested $347 million for assistance to PKOs, of which $228 million was designated for Africa. Through programs such as the African Crisis Response Initiative (ACRI), Africa Contingency Operations Training and Assistance (ACOTA), and the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI), the U.S. government rightly claims to having trained over 250,000 African soldiers in peace support operations.

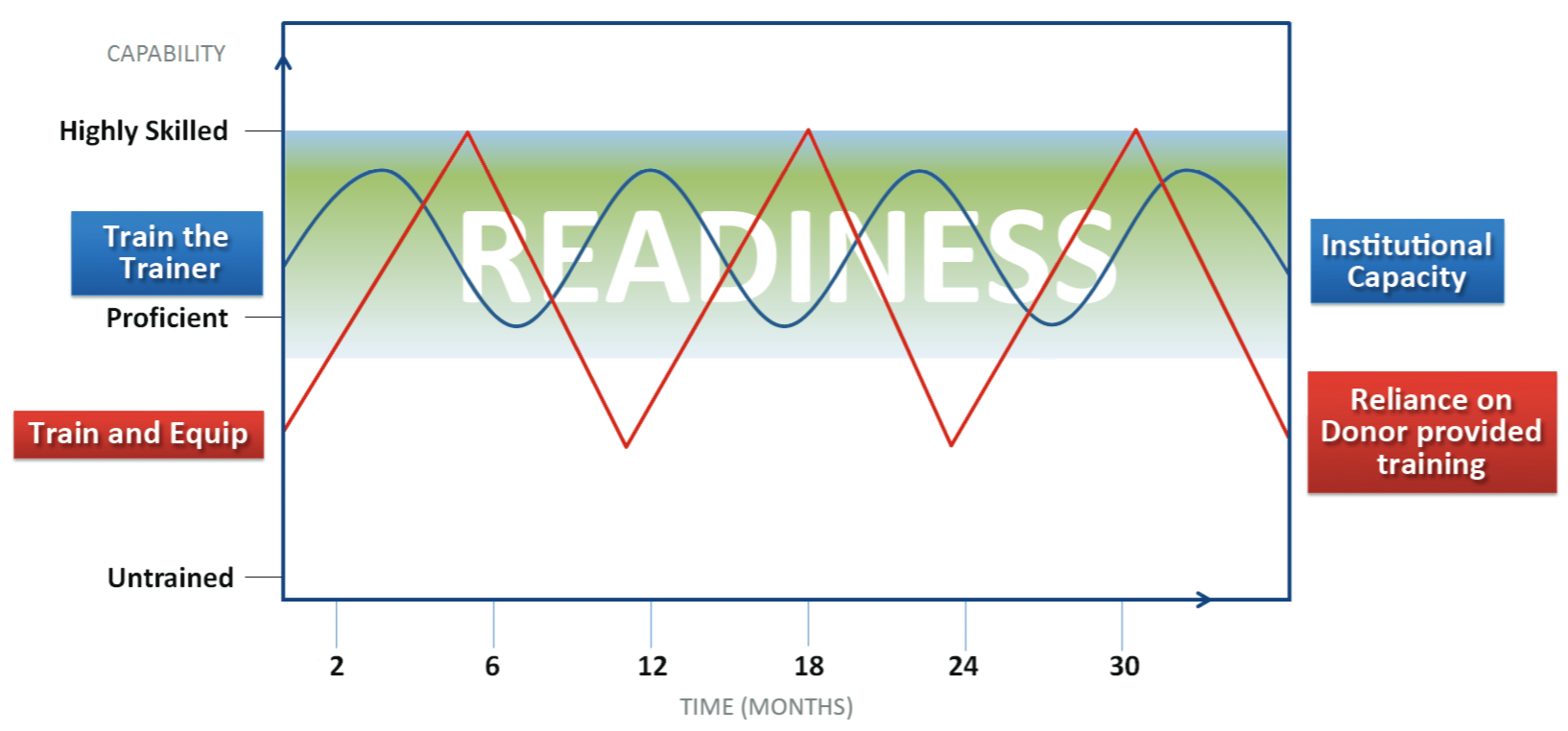

These seemingly impressive numbers suggest that there exists a quarter of a million well-trained African peacekeepers available to deploy on peacekeeping missions. This is not the case. The reality is that all military skills are inherently perishable, and it is inaccurate to reference a cumulative total of trained peacekeepers. A trained peacekeeper in the past is not a trained peacekeeper in the present, nor does a trained peacekeeper in the present indicate an available trained peacekeeper for the future (see Figure 1). There are several reasons why this is so. Soldiers trained to proficiency on military tasks show marked degradation of task retention after just 60 days. Without practice or retraining, proficiency continues to erode to the point that after 180 days there is an estimated 60 percent loss in skill retention.6 With respect to collective task training (team training), the rate of degradation is even more rapid. This is due to both the increased complexity of collective tasks and the difficulty in retaining cohesion of the unit.7

Figure 1. Sustained Readiness

Cohesion of the collective is a recurring constraint to sustainable peacekeeping capability. With African peacekeeping contingents, frequently the unit receiving training is a composite formation cobbled together from multiple organizations and rounded out with individual soldiers who have never previously trained together as a collective. (This is primarily due to insufficient force structure and inadequate levels of deployable soldiers within many African units to meet the troop strength requirements for a standard UN infantry battalion comprised of 3 or 4 company groups of 850 personnel). In this scenario, upon completion of training the cohort disbands and the soldiers return to their parent units and organizations, with collective task proficiency essentially lost. In instances where the trained formation deploys directly into a peace support operation, proficiency is retained longer. However, upon completion of a normal 6-month rotation the formation can no longer be termed a trained peacekeeping asset if it does not retain cohesion and receive sustainment training.

“All military skills are inherently perishable.”

Retaining postdeployment unit cohesion is difficult in any military due to the normal cycle of reassignment, promotion, retention, and replenishment. Hence, the need for institutionalized training within an established professional military education (PME) system is of paramount importance to sustained peacekeeping capability. Within the African context, many states lack an effective PME system to complement the training received from international partners. The result is that acquired knowledge and experience erodes, capacity is not increased, and capability is not retained. Both African states and their international partners must avoid training programs that do not create enduring indigenous capacity to sustain skills. In short, “well-trained security forces are of limited utility, or indeed can even be counterproductive, without the institutional systems and processes to sustain them.”8

Clearly, the key to retention of peacekeeping skills is an indigenous, institutionalized training capability. The United States’ ACOTA program acknowledges this tenet in its mission statement, yet to date there has been limited success in creating sustainable peacekeeping training institutions within Africa.9 At the inception of the ACRI program in 1997, there was a stated focus on “training the trainer.” However, such a methodology has never been fully implemented. When the ACRI program transitioned to ACOTA in 2002, the desire to build institutional capacity remained but, in practice, the program continued to provide training primarily to African soldiers rather than creating professional instructor cadres within African militaries. The trainers standing in front of the trainees were still predominantly American and almost exclusively PMCs.

This inability to shift peacekeeping training responsibilities onto an African cadre is not entirely due to a lack of commitment on the part of ACOTA. In instances where a train-the-trainer approach has been applied, too frequently the African partner nation failed to utilize the trained instructors for their intended purpose, and many were reassigned or deployed shortly after receipt of donor-provided training.10 Interestingly, as more African states commit a portion of their defense force to peace operations on a recurring and near continuous basis, several have seen the utility in establishing dedicated peacekeeping training facilities. However, designating a training site and resourcing a training institution require vastly different levels of commitment. If an international partner is willing to provide instructors, training aids, and resources for a specific training event or exercise, then there is not a perceived advantage for the host nation to incur the cost of manning and operating a training facility on a full-time basis. While this would seem to be a pragmatic approach in a resource-constrained defense budget, it is a model that offers little in the way of institutional longevity. For this reason it is important that peacekeeping training centers are incorporated into a larger PME system. This will not only better ensure sustained capacity, but also create economies of scale with respect to the cost of full-time instructor cadres and required operating resources.

Former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates stated in 2010, “The United States has made great strides in building up the operational capacity of its partners by training and equipping troops and mentoring them in the field. But there has not been enough attention paid to building the institutional capacity.”11 For example, the United States’ GPOI program has spent only 12 percent of its budget on building institutionalized African peacekeeping capacity.12 The majority of this institutional support has gone to the physical establishment of training centers and sites. The next step of manning those facilities with permanent and professional African cadres is still not fully realized, however. Official U.S. policy directs a shift in focus from training peacekeepers to building indigenous peacekeeping capacity.13 Despite this acknowledgement of a need for change, there has not been a corresponding shift in the allocation of U.S. resources. The continuing training of African troop contingents for deployment into crisis areas diverts assets and energy from what should be the priority effort: institution building.14

“The real metric of success is not how many personnel receive training, but rather how well a country sustains capability and maintains operational readiness.”

Considering that the United States has been working to build sustainable African peacekeeping capacity since 1997, it is hard to imagine that there is not more to show for the effort and money spent in the form of sustained capacity. If the enduring focus had been train-the-trainer, the PMC trainers running these programs should have been able to work themselves out of a job. Yet as the ACOTA program works diligently to prepare African soldiers for deployment into the Central African Republic, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Mali, Somalia, or other current hotspots on the continent, the trainers conducting that training are not professional African cadres but still mostly American contractors.

A New Model

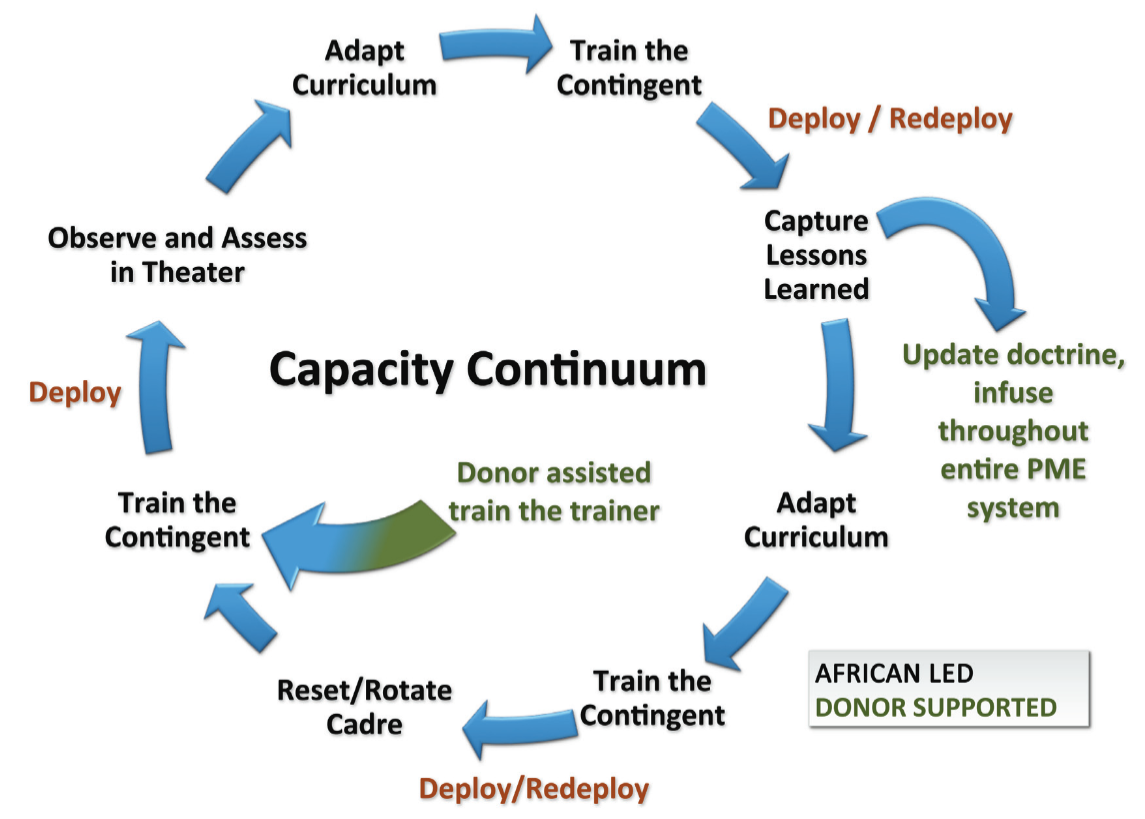

A new model of peacekeeping assistance must focus on building and supporting indigenous institutions—where a professional military instructor cadre trains the soldiers that will comprise peacekeeping contingents (see Figure 2). In this new model, peacekeeping tactics, techniques, and procedures are embedded in doctrine and reinforced throughout all levels of a PME system. Lessons learned and operational experience are captured and incorporated into curricula and training exercises. Under this approach, the real metric of success is not how many personnel receive training, but rather how well a country sustains capability and maintains operational readiness with a capacity to respond to an AU or UN request.

Figure 2. Building Blocks for Sustained Capacity

- Train the trainer: Build African NCO capacity.

- Train the contingent: Africans train Africans.

- Institutionalize: Dedicate training facility or mobile training team concept.

- Retain expertise: Maintain professional instructor cadre within the defense force.

- Sustain: Integrate instructor cadres and curricula within African PME systems.

- Adapt: Capture and analyze operational lessons, update training curricula.

- Optimize resources: Coordinate donor support to ensure complementarity.

The days of Western soldiers standing in front of African soldiers as primary instructors should be long gone. In fact, several African militaries could accurately be characterized as professional peacekeepers with little need for outside training. For example, Ghana, Rwanda, Senegal, and South Africa each have provided troop contingents to UN missions almost continuously for well over a decade. Their operational experience and institutional knowledge far exceed that of the average American PMC. Incorporating these lessons, proficiencies, and experience into African PME systems is the key to sustainable capacity and capability.

Another advantage of removing the Western face from troop training is the opportunity to empower and legitimize host-nation noncommissioned officers (NCOs). When a training instructor stands in front of a formed unit, there is an understood expert-to-novice relationship. Training a cadre of professional instructors prior to a troop contingent training exercise ensures that the recognized expert on the subject matter is not an American contractor but a NCO from the responsible African force. The less active involvement by foreign personnel during training exercises the better. Once the cadre has been trained, the role of international advisors should be to provide training resources and observe. They can then teach, coach, and mentor the African cadre in separate instructor “after action reviews” away from the trainees.

“The operational experience and institutional knowledge [of experienced African troop contingents] will far exceed that of the average American private military contractor.”

Emergent requirements to field trained peacekeepers for missions in areas such as the DRC, Mali, or Somalia will naturally shape the method employed. A deliberate policy decision by both African and partner nations to rapidly create capability to address an urgent need is understandable and will occur on occasion. One cannot discount the short-term impact achieved via T&E missions to prepare thousands of peacekeepers for deployment into crisis areas. However, at issue is the missed opportunity for long-term gains from the millions of dollars spent. If African and partner nations adopt and adhere to a policy of building institutional capacity, the demand for reactionary training diminishes as more TCCs sustain and maintain a higher level of operational readiness. The goal must be to create the conditions where train-and-equip missions are the exception not the rule.

Several African states that are UN TCCs—Nigeria and South Africa to name but two—are in the enviable position of having both a dedicated peacekeeping training center and a fully developed PME system up through defense college level. However, the linkage between operational experience and institutional education has yet to be fully optimized. What is absent is a formal process and organization to capture lessons from the field, analyze them, and then develop and adapt training curricula to sustain and improve performance and capability.

The Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) in Ghana.

The International Peace Support Training Centre (IPSTC) in Kenya and the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) in Ghana are examples that reflect successful partnerships between international actors and African states to create indigenous peacekeeping capacity. While neither of these centers is designed to provide training for formed battalions, they are an excellent resource for sustainment training. As indicated in their mission statements, the principal focus of these institutions is not predeployment training for peacekeeper contingents. They are primarily donor-funded, subregional assets that provide multinational classroom and seminar instruction at the operational and strategic level. These regional centers are not a substitute for institutionalized peacekeeping training capacity within a military’s PME system. However, they can be an effective complement to sustaining and maintaining critical peacekeeping skills.

Sustaining African Peacekeeping Capability

Enhancing capacity and capability is a continuum not an event. Achieving this will require changes from both African governments and international partners. Both parties must ensure that resources and assistance are applied to the lifecycle of a peacekeeping contingent to maximize retention of skill and experience for future units (see Figure 3). This means that in addition to predeployment and postdeployment interaction, mentors should visit a unit in the theater to assess the suitability of the predeployment program of instruction (POI) and then modify the POI as necessary. Capturing lessons learned and incorporating them into specific POIs, general PME curricula, and defense doctrine is a challenge for most militaries, but particularly so for African militaries that struggle with limited resources, underdeveloped institutions, and demanding operational cycles. This is an area of expertise that international military partners can help build.

Figure 3. Enhancing Capacity: A Continuum Not an Event

Donor programs designed to increase the capability of African peacekeepers require a collective approach. Assistance should be coordinated with and complement other international and regional efforts. International assistance must begin with the baseline list of established UN and AU peacekeeping standards (the “United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual” is an excellent foundational document for the basic soldier skills required to ensure interoperability in UN peacekeeping missions). From this baseline, a POI can be adapted to the existing tactics, techniques, procedures, and experiences of the host nation.

In addition to leveraging donor assistance to train instructor cadres and develop PME institutions, African policymakers should selectively identify bilateral partnerships that can provide added value in the form of expertise or resources that transfer a unique or superior capability. Basic soldier skills and traditional collective tasks associated with PKOs can be taught and proficiency achieved in a fairly straightforward and structured fashion. There are UN-approved POIs available that any capable training cadre can adopt and apply.15 However, the more complex tasks and problem sets associated with peace support operations are not rote.

EOD training in Namibia. (Photo: USAFRICOM.)

For example, countering improvised explosive devices (C-IED), explosive ordnance disposal (EOD), and intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) are capabilities the United States can offer to enhance African peacekeeping capability beyond basic soldier skills. Although these skills were honed by the U.S. military during counterinsurgency operations, their application in the PKO environment is increasingly evident. More and more, the threats and situations faced by peacekeepers in the eastern DRC, Mali, and Somalia are asymmetrical in nature, involving nonstate actors possessing varying degrees of capability, equipment, and technology.

Unfortunately, security assistance of this nature is too often lumped under a rubric of “counterterrorism” programs. This is not only too limiting, but can evoke negative connotations. Therefore, it is important to address the range of capabilities required in PKOs and avoid labeling certain military assistance and skillsets too narrowly.

The same principle is true concerning the discourse on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Media coverage of “drone attacks” has nurtured a perception that all UAVs are armed platforms capable of delivering precision strikes against designated individual targets. In fact, few UAV models are designed for or capable of carrying and delivering ordnance. The more common application resides in providing a clearer operational picture to a unit commander. The ability of peacekeeper contingents to effectively use UAVs to see and understand the operating environment is critical to sound decisionmaking, protecting civilians, and overall mandate enforcement.

When entering into military assistance partnerships, it is also worth examining the role of PMCs. There are several benefits for both African and donor nations in utilizing uniformed personnel rather than civilian contractors for PKO training. While PMCs are fully capable and qualified to conduct most training to the same standards as uniformed military trainers, the issue returns to one of short-term versus long-term effects. The professional bonds formed during military-to-military interaction cannot be underestimated. A residual security cooperation benefit is achieved in bilateral defense relationships when uniformed military are training and working side by side with their uniformed partners. At the soldier level, the sharing of experiences and expertise during an exercise is mutually advantageous. With PMCs the interaction is more one sided. While there is a role for PMCs to play in augmenting a military lead during training events, the value of military-to-military interaction endures beyond any specific training event.

In summary, the cornerstone of sustainable peacekeeping capability is institutional training capacity. Entering into security cooperation programs with international partners can be an effective method to build or rapidly advance indigenous institutions. A generic peacekeeping training model in its simplest form is comprised of three phases. In the first phase—train the trainer—international subject matter experts are used as needed to train a host-nation instructor cadre. In the second phase—train the peacekeepers—the international trainers observe and mentor the African instructors in a passive role with little to no interaction with the trainees. The more challenging third phase—sustainment training—requires retention of a professional cadre within the African defense force that endures over time. This requires the will of senior defense and military leadership, and will often necessitate an organizational restructure within the force to create instructor billets that are permanent positions and considered career enhancing.

Donor-provided train-the-trainer programing is not in itself a cure-all for creating institutional capacity. Once a cadre has been formed and trained, the onus is then on the African military to make a commitment to utilize the trainers for their intended purpose. Too often the trainers are diverted to other positions or assignments, resulting in a loss of indigenous instructor expertise. Moreover, African militaries must sustain the existence of the cadre beyond the initial cohort of individuals that received donor training and establish a replenishment cycle for designated and dedicated instructor positions within the defense force structure.

“The goal must be to create the conditions where train-and-equip missions are the exception not the rule.”

Ideally, a professional cadre of peacekeeping trainers would exist within a defense force’s PME system at an institutionalized peacekeeping training school or center. Furthermore, peacekeeping curricula should be incorporated throughout all professional development courses (e.g., platoon and company commander courses, staff colleges, warrant officer courses). While this is an option for the more mature and better resourced defense forces, less endowed militaries can still institutionalize the training program without a designated brick-and-mortar facility or comprehensive PME system. A peacekeeping training cadre organized as a mobile training team (MTT) can effectively prepare and train units to sustain capacity. However, this assumes cohesion and replenishment of the MTT instructor cohort over time. Again, this becomes a matter of will on the part of African defense force leadership to prioritize and resource a professional instructor cadre within the force as a key component of readiness.

African states must better leverage donor assistance to increase and then maintain the operational readiness of their force. African soldiers are the best resource to train African soldiers. African states must not allow themselves to become habitually dependent upon donor support to participate in UN or AU missions. It is in their interest to develop and sustain an indigenous capacity to generate trained and ready peacekeepers. Likewise, donor nations at some point must break from a seemingly perpetual cycle of training hundreds of thousands of African peacekeepers, frequently from the same handful of countries, with little sustained impact. The real shared interest of both parties is the establishment of sustainable peacekeeping capability that is institutionalized within African defense forces. It is time to move beyond the reactionary nature of train-and-equip missions and create enduring capacity.

Notes

- ⇑ Madu Onuorah, “How policy, funding issues clog Nigeria’s UN peacekeeping operations,” The Guardian, June 10, 2013.

- ⇑ Manual on Policies and Procedures Concerning the Reimbursement and Control of Contingent-Owned Equipment of Troop/Police Contributors Participating in Peacekeeping Missions (COE Manual) (UN doc. A/C.5/66/8, October 27, 2011).

- ⇑ Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the operationalisation of the Rapid Deployment Capability of the African Standby Force and the establishment of an “African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crises” (AU doc. RPT/Exp/VI/STCDSS/(i-a)2013, April 29-30, 2013).

- ⇑ By comparison, the United Kingdom (the next largest contributor of bilateral assistance to peacekeeping operations in Africa) allocated $85 million from its Conflict Pool toward Africa in fiscal year 2013.

- ⇑ Congressional Budget Justification, Vol. 2, Foreign Operations, Fiscal Year 2013, U.S. Department of State, 144.

- ⇑ A.M. Rose, M.Y. Czarnolewski, F.E. Gragg, S.H. Austin, Acquisition and Retention of Soldiering Skills, Technical Report 671 (Alexandria: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, February, 1985).

- ⇑ B.D. Adams, R.D.G. Webb, H.A. Angel, and D.J. Bryant, Development and Theories of Collective and Cognitive Skill Retention (Toronto: Defence Research and Development Canada, March 31, 2003).

- ⇑ Quadrennial Defense Review Report, U.S. Department of Defense, February 2010.

- ⇑ Peacekeeping: Thousands Trained but United States is Unlikely to Complete All Activities by 2010 and Some Improvements are Needed, U.S. Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees, June 2008.

- ⇑ Ibid, 22.

- ⇑ Robert M. Gates, “Helping Others Defend Themselves: The Future of U.S. Security Assistance,” Foreign Affairs 89, No. 3 (May/June 2010), 74.

- ⇑ Peacekeeping, 9.

- ⇑ Congressional Budget Justification, 226.

- ⇑ Peacekeeping, 11.

- ⇑ United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual, Volume I, Volume II (New York: UNDPKO/DFS, August 2012).