Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português | Español

Summary

With organized initiatives for demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration (DDR) in 10 African states, there is widespread recognition of the importance of these programs to advancing stability on the continent. Even so, these initiatives are often under-prioritized and -conceptualized, contributing to the high rates of conflict relapse observed in Africa. DDR efforts across Africa over the past decade indicate that DDR cannot substitute for measures that address core conflict drivers and is often hobbled by expedient but fragile efforts to integrate nonstate militias with a national defense force.

Highlights

- Notwithstanding laudable successes, incomplete or poorly conceived disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) initiatives have been key factors to high rates of conflict relapse in Africa.

- Reintegration is the most complex and critical yet least prioritized facet of DDR.

- The decision to integrate former militias into the national army is typically a political expediency that impedes military professionalism and increases the likelihood of human rights abuses and instability.

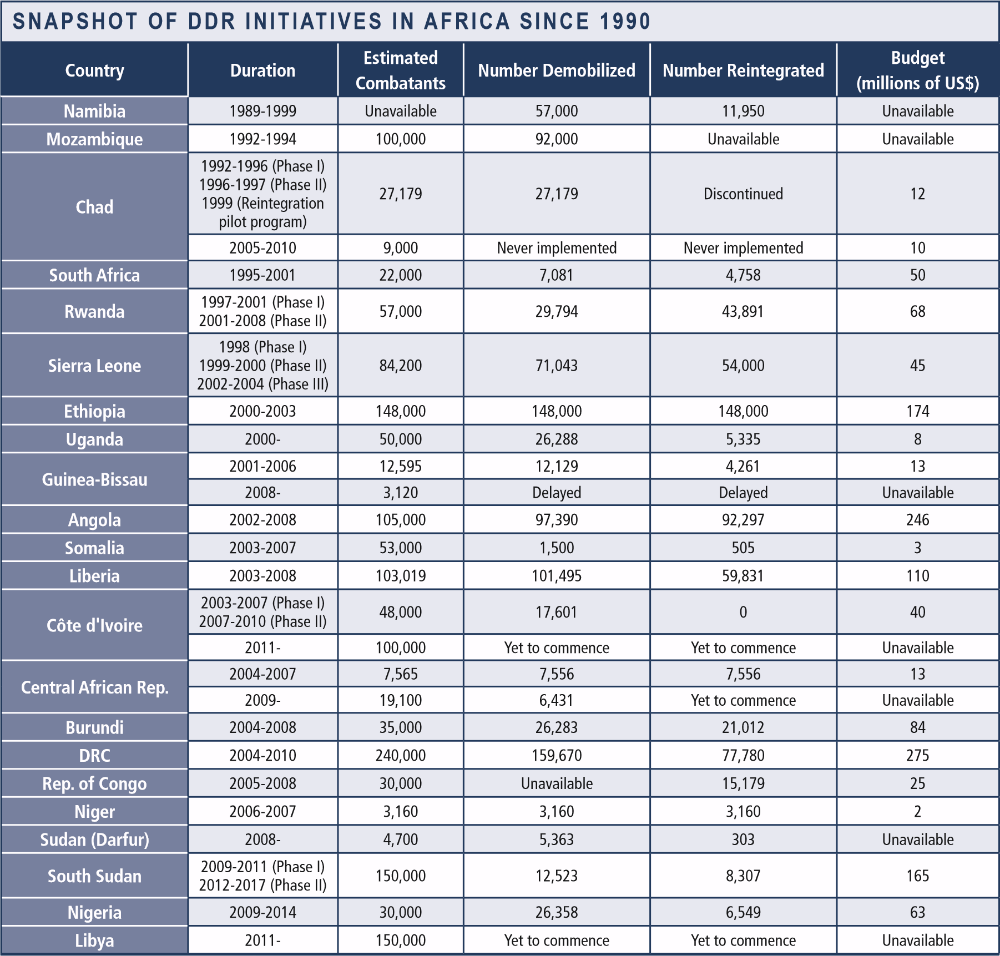

There are approximately 500,000 individuals in a variety of nonstate militias, national armies, and paramilitary groups slated to undergo DDR programs across Africa. This is consistent with the estimated average annual DDR caseload for most of the last decade. As previous large-scale efforts in Angola, Liberia, and Sierra Leone have wound down, new challenges in South Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire, and the Great Lakes region have emerged. Organized DDR initiatives were underway in 10 African states in 2012, and the need for disarmament was apparent in many others.

In Libya, scores of militias emerged during and after the 2011 anti-Qadhafi revolution, and subsequent clashes between them have resulted in hundreds of deaths. Such incidents have focused attention on DDR, but the prevailing volatility has compounded the reluctance among militias to disarm. Libyan authorities estimate that 150,000 combatants need to be disarmed and many judge this issue to be among the most difficult challenges of the post-Qadhafi transition.

Following a decade-long low-intensity conflict that culminated in a 5-month postelectoral crisis in 2011 in which 3,000 people died, Côte d’Ivoire faces immense DDR challenges as well. The United Nations (UN) peacekeeping mission there estimates that up to 100,000 combatants will need to be demobilized from among the former regime’s military, rebel forces, and various partisan paramilitary units. A spate of armed attacks in 2012 killed dozens of civilians and government troops as well as seven UN peacekeepers, indicating that militants remain a threat to stability. Insecurity has also spread to neighboring Liberia and Ghana, as fighters from Côte d’Ivoire have stored arms and launched attacks across their shared borders.

The fledgling government of South Sudan launched a disarmament program to downsize its security forces by 150,000 personnel and is mounting a separate effort to disarm individuals and local militias to stem worsening intercommunal violence. Roughly 20,000 former fighters from the Lord’s Resistance Army and other militias are waiting to complete a DDR process in Uganda. Approximately the same number has been waiting since 2009 for a DDR program to be implemented in the Central African Republic. Frustrated by the delays, some of these militias have again taken up arms, heightening instability. DDR remains a priority in Guinea-Bissau, but has been delayed for years. And new DDR challenges lay on the horizon. In Mali, following a 2012 rebellion launched by northern separatists and the subsequent seizure of several key cities by heavily armed Islamist groups, disarmament and demobilization will be crucial to reversing an increasingly militarized situation. As an African Union peace operation continues to make progress stabilizing Somalia, estimates indicate that at least 53,000 militants there will ultimately need to be disarmed.

Despite the growing need for DDR, previous campaigns in Africa have encountered many difficulties and yielded mixed results. A decade-long DDR program in Africa’s Great Lakes region cost nearly $500 million and disarmed and demobilized 300,000 combatants in 7 countries. However, heavy fighting regularly flares in the region and a resurgent rebellion in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) driven by formerly demobilized forces has resulted in hundreds of deaths, a surge in militia recruitment and mobilization, and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. Dissatisfaction and backsliding among ex-combatants remain common in many DDR campaigns.

The Combatant’s View

Combatants in postconflict settings can be roughly divided into three subsets. Frequently, a significant proportion of armed actors will voluntarily self-demobilize once a viable peace framework seems to be in place. In Burundi, many combatants harbored no deep commitment to a career as a militant and eagerly participated in DDR.1 In many DDR campaigns, up to 20 percent of combatants who complete demobilization claim no subsequent transitional or reintegration benefits.2 In Sierra Leone and Liberia, surveys indicated that 10-15 percent of ex-combatants opted not to participate in DDR at all.3 For self-demobilizers, the availability and configuration of a DDR program is a secondary concern.

A second subset of combatants harbors deeper ties and vested interests in militancy. They are typically senior in rank, and demobilization represents a substantial sacrifice of influence and authority. Often they profit from their role in a militia or the armed forces, whether through illicit taxation or trafficking of minerals and commodities. Some of these combatants may face prosecution or investigation for war crimes, and therefore have strong incentives to remain armed and active. Promises of skills training or reintegration assistance are unlikely to appeal to hardcore combatants.

Many militants in the DRC, for example, remained armed despite lengthy DDR efforts. Years of DDR targeting the Hutu-led Forces Démocratique de Liberation du Rwanda (FDLR) gradually drew thousands of fighters from the bush to disarm, but as the FDLR shrank so did DDR progress. Many senior FDLR fighters profit from the exploitation of valuable mineral reserves in the DRC and face prosecution for their involvement in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, so they are unlikely to disarm through DDR. Likewise, despite the demobilization of roughly 25,000 combatants from other militant groups in the DRC’s Ituri region, which had been a focal point of conflict from the mid-1990s until 2003, some militias remained active and resistant to DDR. Indeed, Ituri experienced a spike in militia attacks and killings in 2012. Other methods, including military operations, legal and diplomatic pressure, and measures to combat illicit revenue generation are needed to deal with hardcore combatants.

A third subset of combatants exists between self-demobilizers and the hardcore. They are hesitant to disarm, fearing that they will be exposed and vulnerable amid an insecure, uncertain, and volatile environment. They lack suitable income-earning alternatives, so may worry that disarmament would result in diminished well being. However, they have little motive or interest in remaining a combatant. They are fence-sitters who need inducements and viable, gradual pathways to reject militancy.

It is with this third subset of combatants that DDR programs can have their biggest impact. By providing adequate opportunities to safely disarm, financial and psychological support to transition to civilian life, and sufficient training and opportunities to sustain themselves, DDR can draw such swing combatants away from militancy. This also indirectly weakens remaining hardcore combatants by depleting the number of their supporters. In Liberia, Sierra Leone, and the DRC, this group was mostly young, lacked extensive training or education, and had few familial or kinship connections that could draw them back to their home communities or serve as a support network and social outlet.

“Incomplete or ineffective reintegration of ex-combatants into civilian life, in turn, risks the greater likelihood of armed criminality.”

While fence-sitting combatants are core constituents of DDR, past campaigns have encountered shortcomings in addressing their needs and interests. The first two components of DDR, disarmament and demobilization, are usually not the problem. Some politically sensitive matters are involved, but they are usually short-lived and pose primarily technical challenges. Assembly sites for disarmament must be situated near areas of militant activity but secured so that arriving combatants do not feel vulnerable. Combatants must be registered, arms must be collected and either secured or destroyed, and cantonment sites for the demobilized must be built. Communication is critical so that prospective participants are aware of the process, its duration, and do not have inflated expectations about its outcomes, which can result in later frustration. However, with proper planning, the disarmament and demobilization steps can be effectively managed and implemented.

Reintegration, by contrast, is far more complex and lengthy. Reintegration involves skills training, loans, job placement, and assistance to resocialize ex-combatants and facilitate their relocation to permanent homes. It is also the stage at which backsliding is most common. In Liberia, ex-combatants who completed disarmament and demobilization demonstrated limited abilities to reintegrate politically, socially, and economically.4 Those who completed disarmament and demobilization in Burundi but then endured long reintegration delays became frustrated and distrustful of DDR. In general, delays in reintegration are linked to escalations in tensions and relapses into armed violence. Incomplete or ineffective reintegration of ex-combatants into civilian life, in turn, risks the greater likelihood of armed criminality.5

Sources: These figures are based on various estimates from multiple United Nations and World Bank documents, commissioned studies, and news reports. Some residual DDR activities continue in countries where past programs have formally ended. Civilian disarmament campaigns in Uganda, South Sudan, Kenya, and elsewhere were omitted because they contain no demobilization or reintegration components.

In many DDR campaigns, momentum ebbs sharply during reintegration. Only half of those who had been demobilized received reintegration assistance in the DRC (see table). Assistance typically included some combination of a stipend paid in installments, vocational and skills training, kits with basic tools and provisions for agricultural or other productive purposes, and some psychological and resocialization assistance. Unfortunately, the assistance was of limited use and duration. Kits were often sold rather than used for their intended purposes. Due to inadequate infrastructure, delivering promised stipends to ex-combatants at regular intervals proved challenging, diminishing trust in the DDR process. The training received was often poorly suited to labor market needs. Two of the most popular sectors in which Congolese ex-combatants worked were transportation and artisanal mining, yet almost no training or assistance were provided for these fields.6 Many ex-combatants had some experience in fishing, agriculture, trading, and other sectors prior to joining a militia, but these preexisting skills were often ignored rather than reinforced during reintegration. Surveys of ex-combatants in Sierra Leone suggested that DDR programs needed to more clearly understand participants’ various incentives—formed through their wartime experiences, their social connections and roots, and their existing wealth and skills—to break their ties with armed groups and integrate into civilian communities.7 In general, mismatches between reintegration plans and the opportunities, skills, preferences, and expectations of ex-combatants are common in many DDR campaigns.

Communities where ex-combatants were relocated were also often uninformed, suspicious, or even resistant to reintegration and DDR more generally. For some communities, the stipends, training, and other assistance given to ex-combatants appeared to be a reward for militancy. Assistance also sometimes created socioeconomic imbalances tilted toward ex-combatants within poor villages and towns. Moreover, given the grave human rights abuses that may have been committed during a conflict, resentment toward ex-combatants could be acute. Lack of consultation and engagement with communities, therefore, could exacerbate these tensions.

Political Realities and Intrusions

Continued bouts of insecurity in the DRC have delayed and reversed DDR gains. Even a clash in an isolated area or across a national border can cause ripple effects into comparatively more stable regions. For example, though they are separated by several hundred kilometers, the emergence in 2012 of the Rwandan-supported M23 rebel group in North Kivu province motivated comparatively quiet militias in the DRC’s Ituri region to make new advances and alliances. The DRC government also moved troops previously deployed in Ituri to North Kivu, leaving a vacuum. Other militia groups subsequently began recruiting and demanding that they be given senior positions in the military and authority over the resource-rich Ituri region as a condition to their participation in DDR.8 These shifts have forced indefinite delays in a final phase of DDR in Ituri. Many combatants scheduled to participate and others already demobilized have since joined new militias, reversing previous gains.

DDR in the DRC exhibited other counterproductive features. Ex-combatants in the DRC were offered two options during demobilization: reintegration into civilian life or integration into the newly established police or military, les Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC). The choice was more or less up to the combatant without consideration of the policy implications. Though nearly 200,000 combatants in the DRC were processed during the first round of national DDR, roughly half were effectively remobilized.9 This approach simultaneously served another objective. The DRC essentially had no security services when a transitional government was established in 2003. Assembling a military and police force from already armed actors seemed a logical expedient. Moreover, it was thought that the option to integrate into the armed forces might allay the apprehensions of combatants and militia commanders about the sacrifice of security and influence that disarmament entailed.

“The option to integrate into the military may have enhanced the appeal of and participation in DDR, but it neglected the inevitable hurdles of achieving the genuine integration of so many militants.”

As appealing as this was, the approach disregarded the realities of the transition in the DRC. The fragmentation of the militias was extensive, severely impeding the ability to unify the nearly 100,000 militants who elected integration into a single military force. For example, combatants led by prominent Congolese militia commander Kakule Sekuli LaFontaine were first demobilized, later opted for integration into the armed forces, and eventually deserted after claiming that other militias had been provided more favorable concessions. They regrouped under LaFontaine in the eastern DRC in 2012 and launched several attacks against government forces to seize weapons. A group of another 150 militants, likewise, deserted the FARDC after learning they were receiving less favorable military ranks and subsequently looted villages and raped dozens of women and children.10 Over the course of two weeks in June 2011 four ex-combatant senior officers who had previously integrated into the armed forces and police separately deserted with several hundred supporters.11

The DRC government resorted to other short-term expedients. According to the DDR plan, ex-combatants that chose to integrate with the military were to be thoroughly assessed, appropriately retrained, and separated from their militia command-and-control structures before integrating into the military. However, an “accelerated integration” program was created so that forces could be more quickly utilized. Eventually, tens of thousands of ex-combatants were deployed with little to no training or vetting.12 Many deserted, reintroducing numerous armed actors into a still volatile region. Many that remained within the FARDC have been ineffective, notorious for human rights abuses, and loyal to their former militia leaders rather than the FARDC chain of command.

The case of the M23 rebellion in the eastern DRC is highly illustrative. Many M23 members served in the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie-Goma (RCD-Goma) militant faction during the 1999-2003 war. In the ensuing DDR effort that commenced in 2006, many of the former RCD-Goma troops refused to participate. Those that agreed to integrate into the FARDC continued to operate under the RCD-Goma hierarchy. In January 2009, many of these units attended so-called accelerated integration while retaining their commandand-control structure and control over mineral-rich territories. In 2012, many of these combatants re-formed as the M23 rebellion and launched new attacks against the FARDC.

The option to integrate into the military may have enhanced the appeal of and participation in DDR, but it neglected the inevitable hurdles of achieving the genuine integration of so many militants, particularly given the likelihood that pockets of ongoing conflict would compel the deployment of an unprepared force of questionable loyalty. This set back previous gains and undermined the DDR mission. Meanwhile, support for reintegration among the DRC’s national leadership was also muted. Extending assistance to combatants—many of whom were erstwhile enemies—appeared to be deprioritized once combatants were disempowered and attention shifted elsewhere.

Contextual Factors

A DDR campaign’s viability is also frequently shaped by preexisting conditions that are independent from the campaign’s implementation or participants. How conflicts end, for instance, has significant implications for subsequent disarmament. Increasingly, conflicts in Africa end through negotiated settlements, and resulting peace agreements typically include provisions for DDR. Some agreements, however, are more detailed than others. Following the conflict in the DRC, for example, the Global and Inclusive Agreement on Transition in the DRC of 2002 provided few specifics on DDR aims and processes. The agreement mentioned disarmament just twice and left the details to be shaped by a Defence Council that was never convened. Essentially, signatories committed to DDR without agreeing to what it entailed. Subsequent DDR was often delayed as individual militias withheld their participation to negotiate better benefits for themselves.

By contrast, the peace arrangements in neighboring Burundi included timetables, technical plans, the composition of the reformed security forces including a balanced representation of senior officers and ethnic groups, and a commitment by authorities to satisfy basic provisions for the disarmed and to work toward longer-term reintegration. In Liberia, the peace agreement specified the role of peacekeeping forces in DDR and established that all signatories and various international organizations would be included in a national DDR commission to oversee the process. While subsequent DDR in Liberia and Burundi were far from problem-free, they were arguably more effective than the program in the DRC. The clarity of the DDR framework in the negotiated settlement was an important head start.

Prevailing economic, labor market, and development conditions also have a significant impact on DDR’s progress. The commitment of many ex-combatants to DDR is greatly influenced by the availability of alternative livelihoods and jobs. These, in turn, are shaped by broader economic, development, and postconflict recovery programs. DDR programs can provide skills training, credit schemes, and other support to ex-combatants as they search for new income-earning opportunities, but if the broader economic recovery is sluggish and opportunities few, DDR alone cannot sustainably change this situation. In northern Uganda, for instance, ex-combatants were often unable to apply newly developed skills due to lack of demand and depressed market conditions.13 This may, in part, explain high rates of criminality among excombatants, who make up 42 percent of the inmates in prisons in northern Uganda.14

The dynamics and scale of previous violence can also have significant implications for DDR. In Sierra Leone, for example, whether ex-combatants served in more violent or abusive armed factions was among the strongest determinants of successful acceptance and reintegration into communities.15 Moreover, the number and composition of groups to be disarmed greatly affects a DDR program. Many of Africa’s lengthy conflicts are characterized by a proliferation of armed groups, poorly organized combatants, and shifting loyalties. Such dynamics have unfolded in Darfur, the Central African Republic, and elsewhere, making it more difficult to identify, communicate with, and assemble combatants.

Refining DDR Tools

DDR campaigns in Africa have made significant achievements. Tens of thousands of former combatants have transitioned into civilian life through various DDR efforts. Many have resettled into communities and alternative livelihoods, thereby reducing the number of armed actors and potential violence and criminality in post conflict and unstable contexts.

However, DDR is no panacea for instability. It is not designed to directly address many conflict drivers, such as political and economic power imbalances that fuel grievances, illicit trafficking that empowers or motivates violent actors, or governance weaknesses that tempt spoilers and prompt communities to turn to self-defense. Conflict can persist and even surge due to factors unrelated to DDR. Without a viable development strategy to advance a post conflict economic recovery, even the best managed DDR campaigns will struggle to reintegrate ex-combatants into a productive civilian life. While many combatants willingly participate in DDR, there are always holdouts. Combatants with stronger incentives to remain mobilized must be addressed through other stabilization and post conflict responses, whether diplomatic, political, judicial, or military.

Conversely, DDR programs should not be envisioned or expanded as a means to address larger post conflict economic recovery, institution building, or stabilization challenges. Such overreach is counterproductive. The success of a DDR program may be contingent upon the progress of a peace settlement, a political transition, or a security sector reform effort, but this does not mean that DDR should be designed to directly achieve these ends or compensate for their shortcomings. An overly expansive DDR program could actually undermine DDR’s prospects and traction by neglecting the needs and interests of DDR’s core constituency—ex-combatants. What DDR can do is help smooth a transition and mitigate the impact of setbacks and other obstacles as part of a broader stabilization effort.

DDR efforts also need to be better analyzed and assessed. There are few assessments of past DDR campaigns in which goals are rigorously and systematically compared against actual outcomes through surveys and collection of data from DDR participants. For instance, though both DDR campaigns in Liberia and Burundi ran concurrently, reintegration stipends in Liberia were roughly half the rate of those provided to ex-combatants in Burundi and distributed less frequently. How these and other differences affected DDR participation or success, however, has not been assessed. So as to more clearly identify and transfer such DDR lessons, campaigns must collect better baseline information on the diversity of backgrounds, needs, and expectations of ex-combatants and cross-reference these with findings following the implementation of the campaign. From this, valuable insights can be derived regarding elements of DDR that were most successful, groups that were more likely to abandon DDR, or those programs that had little noticeable impact.

“[DDR] is not designed to directly address many conflict drivers.”

There are various opportunities to sharpen and strengthen DDR efforts in Africa. A key prerequisite is a well-organized, inclusive, and clearly communicated framework for DDR. Directly and thoroughly identifying DDR processes, including when and where disarmament and demobilization will take place, eligibility criteria, how security will be assured and by whom, what body will oversee DDR and who will participate in it, and firm commitments to reintegration services should be central goals of peace negotiation efforts.16 Though it may be tempting to postpone these discussions should they become contentious and seem to delay the completion of a negotiation process, if they cannot be resolved, then they will linger as serious obstacles to stability and peace.

Communication is a critical component prior to and throughout disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration. A campaign’s process, accessibility, and benefits must be made widely known, often through low-tech mass media such as radio. Additionally, given the expanding use of mobile telephony on the continent, mass SMS can facilitate more interaction between DDR participants, implementers, and communities and should be fully exploited. Moreover, combatants and communities will be far more likely to participate and commit to DDR if the parameters and benefits of DDR are clearly communicated and they have the means to lodge complaints, clarify procedures, request assistance, or otherwise stay connected with DDR administrators.

One promising DDR innovation in recent years was initiated by ex-combatants themselves. In the DRC, the Republic of Congo, South Sudan, and the Central African Republic, many ex-combatants, lacking support from formal DDR programs, created their own professional and social associations.17 These small networks of up to a few dozen individuals served as a way to pool funds and other resources, as a means to share information on employment opportunities, and as a support network during periods of unemployment. As importantly, they provided a sense of inclusion, purpose, and resilience, particularly for fence-sitting ex-combatants whose lack of familial or kinship connections presented major reintegration challenges. In the DRC, many of these associations elected counselors to manage group dynamics and mitigate and resolve disputes.18 Many of these groups were also crucial in building trust and cooperative relationships as excombatants resettled into communities. DDR campaigns could benefit from encouraging these groups at an early stage, using them to more efficiently assess ex-combatant needs and skills, and as a resocialization mechanism.

Ex-combatants will also often cast a wide net in their search for work, so reintegration assistance should be broadly focused so as not to overlook livelihood opportunities for ex-combatants, including in low-skilled or informal sectors. Nor should reintegration be shaped only to respond to ex-combatant interests and incentives. Resettlement communities need to be willing supporters of DDR to ensure success. “Community-based reintegration” should be designed to provide interlinked benefits for both ex-combatants and communities. Short-term projects to rehabilitate or build infrastructure identified as a priority by communities could employ ex-combatants, who would have to participate in order to receive stipend disbursements.19 Such mutually beneficial scenarios can foster deeper linkages and support subsequent DDR.

Political leadership at the national level must also prioritize DDR. Following a devastating civil war in the 1990s, the new government of Sierra Leone worked quickly and thoroughly from 2000 to 2001 to establish a functioning financial management and procurement unit to advance demobilization implementation. Similarly, a strategic planning committee worked closely with a statistical unit to better understand the socioeconomic settings into which ex-combatants were transitioning. Despite severe resource constraints, the government also funded 10 percent of the entire program from its own budget.20 However, in Sierra Leone and elsewhere, DDR momentum is rarely adequately sustained through the critical reintegration phase. In the DRC, government attention and focus shifted away from ex-combatants once they had been disarmed or as new security and political challenges emerged. Incomplete DDR leaves a large pool of latent instability, as recurring instances of desertions and defections from the security services to militia groups in various African contexts attest.

Furthermore, DDR initiatives should emphasize that combatants transition into civilian life, not the security services. In the DRC, the decision to allow tens of thousands of militants to integrate into the newly reestablished military and police contributed to a bloated and highly undisciplined and unprofessional security sector. Following the end of Liberia’s lengthy conflict in 2003, no former militants or soldiers were readmitted into the streamlined military that ultimately emerged there. The 2,000 restructured and retrained members of the Armed Forces of Liberia were only first deployed in 2012, after years of training. In the DRC, the mobilization of tens of thousands of militants fed or created a host of security, human rights, illicit trafficking, and resource management challenges with minimal improvements to stability in the east. Governments should be intensely circumspect when considering the viability of militants and ex-combatants as potential security providers

Colonel Prosper Nzekani Zena (ret.) is an independent consultant and former military professor and trainer with the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He has served in a variety of roles supporting DDR efforts in the DRC for more than a decade, including as a lead advisor to the national disarmament and demobilization program from 2008 to 2010.

Notes

- ⇑ Peter Ulvin, Ex-Combatants in Burundi: Why They Joined, Why They Left, How They Fared, Working Paper No. 3 (Washington, DC: World Bank, October 2007), 11.

- ⇑ MDRP Final Report: Overview of Program Achievements (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2010), 24.

- ⇑James Pugel, “What the Fighters Say: A Survey of ExCombatants in Liberia February-March 2006,” United Nations Development Programme, April 2007. Macartan Humphreys and Jeremy M. Weinstein, “Demobilization and Reintegration,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 51, no. 4 (2007): 549.

- ⇑ Pugel, 66.

- ⇑ Nelson Alusala, Reintegrating Ex-Combatants in the Great Lakes Region: Lessons Learned (Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2011), 96.

- ⇑ Guy Lamb, Nelson Alusala, Gregory Mthembu-Salter, and Jean-Marie Gasana, Rumours of Peace, Whispers of War: Assessment of the Reintegration of Ex-Combatants into Civilian Life in North Kivu, South Kivu and Ituri Democratic Republic of Congo (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012), 17-20.

- ⇑ Humphreys and Weinstein, 563.

- ⇑ Henning Tamm, “Coalitions and Defections in a Context of Uncertainty – A Report from Ituri (Part I & II),” Congo Siasa, August 27, 2012.

- ⇑ Henri Boshoff, “Completing the Demobilisation, Disarmament, and Reintegration Process of Armed Groups in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Link to Security Sector Reform of FARDC: Mission Difficult!” Institute for Security Studies, 23 November 2010, 3.

- ⇑ Lamb, Alusala, Mthembu-Salter, and Gasana, 9.

- ⇑ “Troubles in the Integration of Armed Groups,” Congo Siasa, June 14, 2011.

- ⇑ “DDR in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Program Update,” World Bank, September 2009.

- ⇑ Anthony Finn, “The Drivers of Reporter Reintegration in Northern Uganda,” World Bank, January 2012, 2, 17, and 20.

- ⇑ “Lack of Funding Stalls Ex-Combatants’ Reintegration,” IRIN, June 18, 2012.

- ⇑ Humphreys and Weinstein, 547-548.

- ⇑ Ibid.

- ⇑ Guy Lamb, Assessing the Reintegration of Ex-Combatants in the Context of Instability and Informal Economies: The Case of the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012), 60. Alusala, 2011, 9.

- ⇑ Natacha Lemasle, “From Conflict to Resilience: ExCombatant Trade Associations in Post Conflict,” World Bank, January 2012.

- ⇑ Lamb, 2012, 27.

- ⇑ Severine Rugumamu and Osman Gbla, “Studies in Reconstruction and Capacity Building in Postconflict Countries in Africa: Some Lessons from Sierra Leone,” The African Capacity Building Foundation, May 2004.