Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Summary

Despite growing concerns across the Sahel and Maghreb over the increasing potency of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, the diffusion of heavily armed mercenaries from Libya, the expanding influence of arms and drugs trafficking, and the widening lethality of Boko Haram, regional security cooperation to address these transnational threats remains fragmented. Algeria is well-positioned to play a central role in defining this cooperation, but must first reconcile the complex domestic, regional, and international considerations that shape its decision-making.

(Photo: Magharebia)

Highlights

- Efforts to counter al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s (AQIM) growing influence in both the Maghreb and the Sahel are fragmented because of the inability of neighbors to forge collaborative partnerships.

- Algeria faces inverse incentives to combat AQIM outside of Algiers as it gains much of its geostrategic leverage by maintaining overstated perceptions of a serious terrorism threat.

- The Algerian government’s limited legitimacy, primarily derived from its ability to deliver stability, constrains a more comprehensive regional strategy.

The growing virulence of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has heightened concerns of instability across the Maghreb and Sahel. In recent years, AQIM militias have conducted operations across wide swaths of northern Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and southern Algeria. Mixing abduction of foreigners, car and cigarette smuggling, drug trafficking, and arms dealing, many consider AQIM’s motivations more criminal than political or religious. This view was reinforced by a “summit” between Colombian drug traffickers and AQIM, represented by Abdelkarim Targui, known as “the Tuareg,” held in Guinea Bissau in late October 2010.1

Kidnappings of Westerners are prioritized for the sensational media coverage generated, providing the group more visibility, leverage, and revenue (estimated at $70 million in recent years). In the process, AQIM has reportedly stockpiled significant quantities of arms and cash. High-profile abductions, in turn, threaten vital tourism and economic investments, such as the Trans-Sahara Gas Pipeline intended to transport Nigerian gas across Niger and Algeria to Europe by 2015.

Risks of instability have been further heightened with the proliferation of weapons that have flowed into the region following the collapse of the Qadhafi regime in Libya. Looted arms and the return of experienced mercenaries threaten to bolster the capacity of AQIM, the violence of illicit trafficking, and the risk of insurgency in a number of Sahelian countries. The reemergence of Tuareg rebel groups in northern Mali resulting in fierce clashes with government troops in the towns of Aguelhok and Tessalit in January 2012 underscores this concern.

There is also evidence of collaboration between AQIM and Boko Haram, the Nigeria-based radical Islamist organization that has been responsible for a growing number of violent attacks including the suicide bombing of the UN headquarters in Abuja in August 2011 that killed 24 people and a spate of bombings in January 2012 that left more than 200 dead in Kano, Nigeria’s second largest city. Nigerian intelligence services have reported that some members of Boko Haram were recruited by an Algerian, Khaled Bernaoui, and trained in a southern Algerian camp as far back as 2006.2

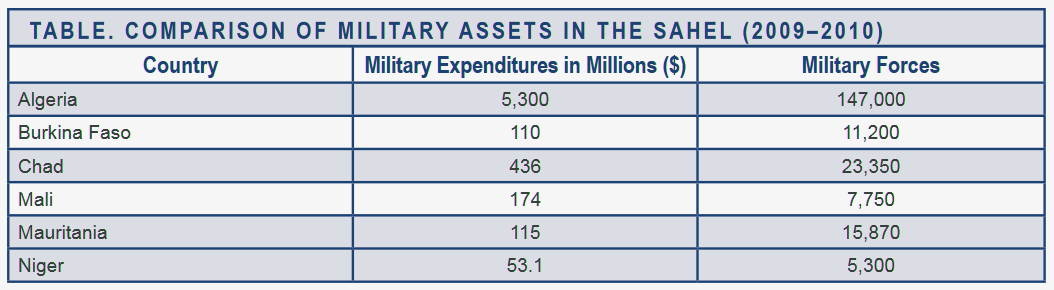

Despite the serious implications and transnational nature of these threats, regional security cooperation remains fragmented. Algeria is seemingly well-positioned to play a leading role in such cooperative security effort. The largest country in the Maghreb, Algeria lies at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, the Arab World, and Africa. It is a member of numerous regional and international organizations such as the Organization of the Islamic Conference, the Arab League, the African Union, NATO’s Mediterranean Dialogue, and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development. With a $200 billion ecoomy and sizable oil and gas reserves (which account for 97 percent of exports), Algeria is the wealthiest country in the region, committing six-fold more resources to its military budget than all of its Sahelian neighbors combined (see table). In addition to being the largest, Algeria’s military is also considered the region’s best equipped and most battle-tested. Despite these assets, Algeria has been largely unsuccessful in filling the leadership gap in the region. This analysis examines why this is the case—and the implications it poses for regional security.

Source: SIPRI Yearbook 2010: Armaments, Disarmaments and International Security (Stokholm: SIPRI, 2010); The Military Balance 2010 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2010).

What Kind of Cooperation to Counter Which Threats?

Despite its Algerian origins, Algerian authorities deny the existence of a connection between Algeria’s domestic terrorist groups and AQIM. Rather, they see AQIM as a new type of terrorist organization driven by its extremist ideology. Sahelian states, in contrast, stress the criminal nature of the group, with its heavy engagement in drug and arms trafficking, as the most dangerous aspect of this regional threat.

The inability to even define the enemy is at the root of the fragmented regional response. This divergence is punctuated by frequent disagreements and a major power imbalance that shapes how each side approaches the threat. With military capabilities superior to those of the Sahelian states, Algeria considers its approach, born from the experience of fighting extremists during its brutal 1990s civil war, to take precedence. The Sahelian states, however, oppose Algeria’s one-dimensional military focus that neglects the economic, social, and political considerations that Sahelian countries see as intertwined with stability in the region. They reason that if the Algerian army has been unable to eliminate terrorism on its own soil over the past two decades using force alone, then why would such an approach work regionally?3

Complicating the matter is the hybrid nature of AQIM itself. The group is split between a northern cell, which leads terrorist attacks in Kabylia and the Algiers hinterland, and two southern cells involved in abductions and organized crime in the Sahel (see map). The group’s dispersed geographic networks appear to act autonomously, or even in competition, rather than in coordination with one another. In some ways, AQIM remains fundamentally Algerian in character and leadership. In others, it is becoming a regional insurgency successfully integrated into local communities and cooperating with government and security officials as well as with local drug traffickers (among them Sahrawi from the disputed Western Sahara territory) and other criminal organizations.4

The result is that when faced with an upsurge of AQIM attacks and kidnappings, each country responds in accordance with its own perception of the threat, heavily influenced by their respective domestic policy interests, with disparate, largely uncoordinated operational undertakings.

As part of these disjointed efforts, Algiers has tried ceaselessly to centralize “the war against terror” in the Sahara and Sahel by making itself the pivotal actor. In April 2010, a Joint Military Command (JMC) comprising Algeria, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger was set up in Tamanrasset, Algeria. This committee was supposed to implement a new regional security plan with joint monitoring forces that were expected to total 75,000, though these forces have yet to be committed.

Such regional initiatives are frequently undermined by Algeria’s fear that its partners are operating independently—to the detriment of Algiers’ interests. For example, a series of Mauritanian counterterrorism operations from July 2010 through February 2011 (the latter of which foiled a plot to assassinate Mauritanian President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz) and a joint France-Niger operation in February 2011 against the kidnappers of two young French citizens were perceived by Algiers as deeply threatening. Rather than encourage such efforts, the Algerian government feared the creation of regional alliances from which it would be excluded, especially since relations between Mauritania and Morocco had improved since Aziz was elected in July 2009.5 On September 26, 2010, Algeria convened an emergency meeting of the defense chiefs of staff from the Sahelian countries in Tamanrasset in an attempt to regain control over regional planning and cooperation. This meeting led to the establishment of a Central Intelligence Cell to facilitate coordination among Saharan and Sahelian countries—based in the Algerian capital far from the attacks that took place in the Sahel.

When G8 security experts subsequently met in Bamako on October 13, 2010, with Morocco participating, Algeria was infuriated. It declined the invitation and reiterated its opposition to any joint decisionmaking involving Western countries.

There have been some signs of cooperation, with the first meeting of the JMC in Bamako held on April 29, 2011, and the establishment of a regional security agenda in May of that year. Moreover, motivated by the risk of instability spilling over from Libya, the defense chiefs from Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Mauritania recommitted themselves to the objectives of the JMC.

At the operational level, on June 2, 2011, Special Forces from Algeria, Mali, and Niger conducted their first joint exercises in the border region between the three countries in anticipation of the risks coming from the crisis in Libya. On June 9, 2011, in Ségou, Mali, Mauritanian and Malian troops successfully coordinated a sophisticated attack in the Wagadou forest that neutralized an AQIM supply camp. And, in December 2011, Algeria for the first time sent military instructors to northern Mali.

Nevertheless, these “successes” do not overcome fundamental differences over the nature of the threat in the Saharan/Sahelian region and the divergent approaches needed to eradicate these threats.

Lack of Trust

Limited regional cooperation is also a result of limited trust. Algeria believes Mali to be the “weak link of the chain” and uncommitted to the fight against AQIM. Algiers questions the trustworthiness of the Malian government vis-à-vis the widening AQIM network and the Malians’ ability to share and protect intelligence needed for regional cooperation. Algeria particularly resents Mali’s willingness to facilitate ransom payments to AQIM to free European hostages, a practice that Algeria strongly opposes.

Meanwhile, security officials from Sahelian states view terrorism as an Algerian export—most of AQIM’s leaders are Algerian. This builds on widely held impressions that by infiltrating earlier Algerian-based terrorist groups the Algerian intelligence service, the Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité, effectively drove Algerian jihadists to the Sahel.

Algeria’s complex relationship in the Sahel is also rooted in the role that Algiers is thought to have played in supporting rebellions of Tuaregs, both in Mali and Niger, as part of Algerian efforts to counter Libyan domination of the Sahara. Algeria later served as a mediator in the peace accords that ended the uprisings in Mali in 1991 and 2006.

“If the Algerian army has been unable to eliminate terrorism on its own soil over the past two decades using force alone, then why would such an approach work regionally?”

Algeria’s regional credibility is further stymied by a series of paradoxes. Algeria is considered to have one of the Maghreb’s most capable militaries and takes pride in having crushed the violent Islamist extremist insurgency of the 1990s. Still, with 938 attacks since 2001, Algeria continues to be plagued by higher levels of terrorist violence than other countries in either the Maghreb or Sahel. (There have been 20 attacks in Mauritania, 35 in Niger, and 41 in Mali during the same period). Algeria, accordingly, continues to be classified as facing an “extreme risk” of terrorism, in the same category as Colombia and Somalia.6

Algeria, similarly, faces mixed incentives to aggressively combat terrorism outside its borders. The government has built a reputation internationally as being the most hard-line state in the region against Islamist terrorism and extremism. This has greatly enhanced Algeria’s geostrategic importance and the advantages of maintaining perceptions of an ongoing threat, particularly one that is nearby but does not pose an immediate threat to the Algerian regime.

Despite its reputation for aggressively countering extremism, the Algerian army has rarely been involved in military engagements outside its borders and has been reticent to participate in joint operations with its neighbors against AQIM. For that matter, Algeria does not have a robust military presence in its own southern region. A June 30, 2011, attack by AQIM on Algerian security forces in Tamanrasset province that killed 11 gendarmes and border guards as well as a February 2011 kidnapping of an Italian tourist in nearby Djanet province point to Algeria’s exposure in the region. Rather, its counterterrorist operations are concentrated in its northern provinces of Kabylia and Algiers. Like its Sahelian neighbors, the Algerian government is incapable of maintaining control over its entire territory. Thus, contrary to the government’s claims of military superiority and operational experience in desert zones, the reality on the ground is considerably different.

“Algeria’s imbalanced focus on security and energy has prevented it from building on its strategic location as a gateway to the Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa.”

Algeria’s poorer Sahelian neighbors are also often the playing field for the ongoing competition between Maghrebian rivals. Yet, unlike Morocco and Libya, which have invested heavily in Sahelian and Sub-Saharan Africa, Algeria’s imbalanced focus on security and energy has prevented it from building on its strategic location as a gateway to the Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Illustratively, the Trans-Sahara Highway (“African Unity Highway”) was long touted as a symbol of Algeria’s links to the Sahel. This major North-South route designed in 1971 was to traverse the 3,000-kilometer length of Algeria through to marginalized northern Mali and the Tuareg regions. However, work on the highway stopped at Tamanrasset in 1978 rather than continuing through to West Africa as originally planned.7

A Military-dominated State

To understand the Algerian government’s fixation on security, it is important to recognize the central role the army played in the construction of the Algerian state. The 7-year independence war (November 1954−July 1962) laid the foundation for violent clashes between militias and civilians within the Algerian resistance. Three years after independence, a June 1965 coup d’état by Houari Boumédienne marked the ascendancy of the military and the start of the one-party era. This resulted in the creation of a security state in which public order, coercion, and law enforcement measures prevailed over representative institutions. After the 1992 coup d’état, which marked the end of Algeria’s first experience with democracy and set the stage for the civil war of the 1990s, a declaration of a state of emergency, which continued for 19 years without parliamentary approval before being officially rescinded in 2011, was one of the tools used to justify expansive mandates and authorities for the security sector.

The war economy generated by Islamist violence in the 1990s and the subsequent repression of civilians not only helped maintain the lack of transparency in Algerian governance but also expand corruption networks (known as trabendo), thereby establishing a mafia-like “bazaar economy.”

“Having benefitted to such an extent from its strong posture on combating terrorism, Algeria is inclined to apply a wide terrorism lens to security threats in the Sahel.”

The army’s apparent withdrawal from politics in the early 2000s shielded it from responsibility for abuses that the civilian government has subsequently committed. However, by ruling but not governing,8 the military has maintained its prerogative to formulate and execute foreign and domestic policy. Accordingly, the “demilitarization of politics” in the 2000s—which could have produced a clean break at the highest levels of government—actually only perpetuated the “bunker state.”9

This was reinforced by the surge in counterterrorism efforts globally after 2001, resulting in an unprecedented increase in Algeria’s military spending over the past 10 years. In just 3 years, its defense budget tripled, reaching $5.3 billion in 2009. U.S. military exports to Algeria nearly quadrupled in the decade following 2001, reaching $800 million.10 The country’s defense budget ranks ninth in the world, first in the Maghreb, and second on the African continent, after South Africa.11 Russia is Algeria’s largest arms supplier. In 2006, Algeria negotiated to purchase $7.5 billion in equipment from Moscow in exchange for the cancellation of Algeria’s estimated $4.7 billion debt, and in 2010 it signed an agreement to purchase 16 Sukhoi fighter planes.12

Having benefitted to such an extent from its strong posture on combating terrorism, Algeria is inclined to apply a wide terrorism lens to security threats in the Sahel.

At the domestic level, presenting terrorism as an indefinite, elusive threat that is extendable in time and space is a way to subject Algerian society to the security diktat, to maintain a de-facto permanent state of emergency, and to postpone indefinitely any transition to democracy. By blurring the lines between counterterrorism and stability and by equating Islamism with insecurity, the Algerian government has managed to perpetuate and consolidate its authoritarianism.

Herein lays the greatest paradox of the Algerian security discourse: by relying on the state’s coercive capacity, the government confirms its lack of legitimacy. As a result, the government must continually justify its actions both at home and abroad. For this reason, although Algeria appears stable and strong, it is actually a weak state struggling to control its territory, protect its borders, safeguard its citizens, and resolve social issues that have been manifest throughout the country during the past decade in the form of riots, demonstrations, strikes, and, more recently, self-immolations. According to the Algerian Minister of Interior, there were over 9,000 such incidents in 2010 alone.13

Steps Needed to Improve Security Cooperation in the Sahel

The fall of the Qadhafi regime and the resulting heightened risk of instability provide new impetus for greater security cooperation between the Maghreb and Sahel. All states across these regions recognize the substantial strains they face and the need for a fresh calculus moving forward. This includes Algeria, which, fearing the spread of extremism, feels more compelled to take action in the Sahel than at any time in the past decade. However, Algeria’s ambitions for leadership will only be credible and attainable once a shared Mediterranean and African strategic vision has been defined.

Diversify Regional Counterterrorism Effort

Since the threat in the Sahel is best described as narcoterrorism, security forces alone are not enough to be effective or build sustainable alliances. A long-term, win-win neighborly policy is essential:

- With its abundant financial resources, Algeria is in a position to take advantage of the sub-regional economic vacuum created by the fall of Qadhafi by investing heavily in local development initiatives in the neglected areas of the Sahara-Sahel, i.e. Tuareg and Tubu territories, and other ungoverned cross-border areas. This would create jobs and opportunities for these populations—diminishing the economic attraction of criminal activities and extremist messages. Such investments would also help demonstrate genuine commitment and shared interests with its neighbors.

- Deepening economic integration between Maghrebian, Sahelian, and Sub-Saharan partners through joint infrastructural projects such as building roads, railways, and pipelines would also increase the accessibility of marginalized regions. The $69 million Special Program for Peace Security and Development in northern Mali, which is part of the national security strategy Mali adopted in 2009 aimed at curbing extremism, is a model of such investment. So is Mauritania’s Program for the Prevention of Conflicts and the Consolidation of Social Cohesion led by black Mauritanian returnees, which is aimed at promoting the rights of marginalized populations.

Joint Commitments of Forces in Sahel.

Intra-regional battalions should be created urgently with the capacity to undertake joint transnational operations along border areas. Counterterrorism and transnational threats can no longer be understood on the basis of the inviolability of borders. Rather, stabilization efforts must be structured around integrated regional zones grappling with the same problems. Along these lines, the intra-regional force structure must develop a more efficient intelligence-sharing capability since, given the nature of the threat, the monitoring of information is more crucial than it is in conventional military operations.

These joint security patrols should include the Tuaregs. AQIM’s violent tactics are not seducing the vast majority of people in the border regions. The group’s ability to mobilize significant popular support, however, is raising concerns among local leaders. Gaining Tuareg participation in the stabilization effort would tap their intimate knowledge of the terrain and population and would allow Tuaregs (including those who recently came back from Libya) to play an active role in the defense of their traditional nomadic territories. From an operational point of view, this would also enhance military readiness and precision against an enemy that is mobile, flexible, and proactive.

Meanwhile, recognizing the importance of drug trafficking to AQIM’s operations, the territory of action should be enlarged beyond the Sahel to involve Burkina Faso, Senegal, Morocco, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, and Nigeria—all key actors in the transit of cocaine on the continent.

Reduce Role of Military in Algerian Politics.

Algeria will not be able to indefinitely maintain its system of military-based governance. Still distrustful of political and military elites, Algerians are not convinced of the authenticity of reforms announced by President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in April 2011 in response to mounting domestic pressure from pro-democracy organizations. The coercion exerted by the armed forces and intelligence services coupled with the military’s control over economic and social activities has engendered deep resentment within Algerian society, heightening the risk of social unrest.

Following regime changes in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, such pressures can be expected to grow. Experience from military transitions in Latin America, South Korea, and Indonesia, moreover, indicate that it is in the interests of the military to lead the reform process rather than wait for the momentum for change to build on its own.14 While perceived as threatening, the shifting regional context actually provides the military government an opportunity for a respectful transfer of power and an end to the nearly constant de-facto state of emergency that has proved costly, limiting, and ultimately counterproductive. Three conditions are necessary for these reforms:

- Active-duty generals must withdraw from economic affairs in favor of a truly competitive private sector in order to build a more dynamic economy based on innovation, merit, and the rule of law, which will in turn attract international investment.

- The culture of political violence, justified as necessary to stamp out terrorist groups, must be abandoned.

- A greater share of the government’s extensive revenues must be invested in infrastructure and services that benefit the general population so as to demonstrate tangible improvements in levels of well-being and thereby augment domestic stability.

Laurence Aïda Ammour is an International Security and Defense Consultant at GéopoliSud Consultance and Research Fellow in Les Afriques dans le Monde at the Institute for Political Science in Bordeaux.

Notes

- ⇑ “Une réunion secrète des cartels de la drogue en Guinée Bissau, AQMI présente,” Sahel Intelligence, November 3, 2010.

- ⇑ Laurence Aïda Ammour, Flux, Réseaux et Circuits de la criminalité organisée au Sahara-Sahel et en Afrique de l’Ouest, Cahier du Cerem No. 13 (Paris: IRSEM, December 2009), 72; Prince Ofori-Atta, “Nigeria: al-Qaeda Presence in Nigeria has been Kept Under Wraps,” Afrik-News, August 3, 2009.

- ⇑ “Aqmi: pourquoi Bamako refuse d’y aller,” Jeune Afrique, September 24, 2010.

- ⇑ Cédric Jourde, Sifting Through the Layers of Insecurity in the Sahel: The Case of Mauritania, Africa Security Brief No. 15 (Washington, DC: NDU Press, September 2011).

- ⇑ Laurence Aïda Ammour, La Mauritanie au carrefour des menaces régionales, Notes Internacionals No. 19, (Barcelona: Barcelona Centre for International Affairs, October 2009). Reflective of the ongoing juggling for influence among Maghrebian rivals, Aziz subsequently made a trip to Algiers in December 2011.

- ⇑ 2011 Terrorism Risk Index. British Maplecroft. August 3, 2011.

- ⇑ Back on the agenda 36 years later, 2 sections of the road toward the Malian border (Tamanrasset-Timiaouine and Tamanrasset-Tinzaouatine) are expected to be completed by 2014.

- ⇑ Steven Cook, The Military and Political Development in Egypt, Algeria, and Turkey (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

- ⇑ Clement Moore Henry and Robert Springborg, Globalization and the Politics of Development in the Middle East (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- ⇑ “Algeria Country Report,” Center for Defense Information, 2007.

- ⇑ SIPRI Yearbook 2010: Armaments, Disarmaments and International Security (Stokholm: SIPRI, 2010); The Military Balance 2010 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2010).

- ⇑ Antonio Sánchez Andrés, “Political-Economic Relations Between Russia and North Africa,” Real Instituto Elcano, November 7, 2006.

- ⇑ Idir Tazerout, “Ce que nous réservent les 20 prochaines années,” L’Expression, July 24, 2011; Claire Spencer, “Algeria: North Africa’s Exception?” Chatham House, August 30, 2011.

- ⇑ Stephen Haggard and Robert R. Kaufman, The Political Economy of Democratic Transitions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).