Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Summary

Increasing narcotrafficking and a more active Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb are elevating concerns over instability in the Sahel. However, the region’s threats are more complex than what is observable on the surface. Rather, security concerns are typically characterized by multiple, competing, and fluctuating interests at the local, national, and regional levels. Effectively responding to these threats requires in-depth understanding of the multiple contextual layers in which illicit actors operate.

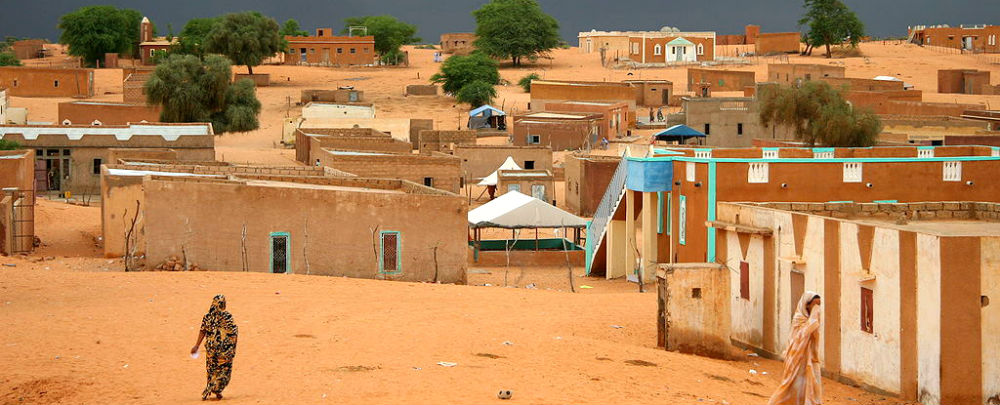

Bareina, a small desert village in the south of Mauritania. (Photo: Ferdinand Reus)

Highlights

- Security threats in the Sahel are characterized by layers of intertwined and crosscutting interests at the local, national, and regional levels.

- International partners’ misunderstanding of these complex dynamics leaves them susceptible to manipulation by illegitimate national actors.

- Regional cooperation against transnational illicit trafficking and terrorism is hamstrung by governments that have calculated that their international standing is enhanced by the perpetuation of instability.

Until recently, the Sahel (as-Sahil), literally the “shore” of the Saharan “sea,” rarely made headlines. Nevertheless, the expanding nexus of illicit trafficking and transnational Islamist terrorism—and the increasingly serious risk this poses to instability in the region and to international security—is attracting growing attention. These concerns will likely mount as al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) attempts to use the window of opportunity presented by the Arab Spring to re-establish itself in North Africa while transitional governments there devote much of their energy to rebuilding state institutions. In turn, an unstable North Africa, especially Libya, could further exacerbate insecurity in the Sahel as unsecured weapons and trained mercenaries filter their way into the region.

As the spotlight on the Sahel widens, analytic shortcuts are perpetuating a superficial understanding of the region’s security dynamics. Suboptimal policies are the result. Beyond the common perceptions of states, terrorists, and smugglers engaging one another across a sparsely populated territory, a more complicated reality exists. Rivalries among tribal groups, the state, private interests of government officials, castes, and others lead to constantly shifting local and regional political and economic arrangements. Understanding these layers of influence is vital to addressing the security challenges facing Mauritania and the broader Sahel.

Muslim, Sparsely Populated, and Weak?

The lens most often used by analysts to decipher Mauritanian politics highlights the expansive territory, largely comprised of uninhabited desert, in which its 3.2 million citizens live. It is also one of the poorest countries in the world. Its government agencies are underfinanced, lack adequate capacity, and, as a consequence, are incapable of monitoring its vast territory. Combined with cultural factors (for example, the prevalence of Islam), Mauritania, like most of its regional neighbors, is an easy target and haven for traffickers and armed groups, including transnational Islamist terrorist movements.

A number of recent events substantiate this assessment. Deadly attacks on remote Mauritanian military garrisons by terrorist groups have occurred multiple times since 2005. Foreign embassies have been targeted by gunmen and suicide bombers. Western tourists and humanitarian assistance workers have been regularly assassinated or kidnapped for ransom by Islamist extremists since December 2007. In 2010, a group of alleged suicide bombers was intercepted and neutralized in Nouakchott before it could attack its targets. During the past 2 years, Mauritanian security forces have periodically clashed with armed groups across the border in Mali (once, in 2010, with support from French troops). In other Sahelian countries such as Niger, the situation is also problematic. Five employees of the French nuclear company AREVA were kidnapped and are still held hostage to this day, while two young Frenchmen were kidnapped in the center of Niger’s capital and killed when their abductors and French Special Forces clashed a few hours later.

These acts of violence have been perpetrated by battalions (katiba) and small brigades (saraya) affiliated with the region’s most active Islamist terrorist organization, al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, known more commonly as AQIM. However, as the trial and death sentences of three Mauritanians in October 2010 for terrorist ties indicate, local extremist groups such as Ansar al-Islam (the Partisans of Islam) and Ansar Allah al-Murabitun fi Bilad al-Shinqit (the Murabitun Partisans of God in the Country of Shinqit)1 have played a role too.

Insecurity in the region is also fed by extensive transborder smuggling—directly via weapons trafficked and combatants hired, and because terrorist groups or their partners reap huge profits from it, which they reinvest in violent activities.

These usual suspects of insecurity in the Sahel—Islam, vast uninhabited land, weak states—do indeed play a significant role in regional instability, but they fall short of explaining all the dynamics of insecurity.2 At times, the state is the instigator of armed violence, such as the 1989–1990 killing of hundreds of Haalpulaaren, Sooninko, and Wolof—ethnic minorities known as “Black Africans”—at the hands of Arabic-speaking officers of the Mauritanian security forces. This was accompanied by the violent deportation of about 80,000 others. An amnesty law that protects security personnel from any form of judicial prosecution for past abuses perpetuates these grievances and reinforces suspicions of the state and its security forces.

Not only is insecurity in the Sahel more complex than it appears, but so are the political actors involved, the reasons they engage one another, and the intersections of local, national, and regional dynamics.

The Overlay of Micropolitics and Regional Rivalries

Security analysts of the Sahel often first adopt a global perspective and then zoom in on the domestic politics of a given country. But they rarely zoom in enough. This is necessary, however, to get past conventional myths that frame analyses of security in the region.

Take the case of illicit trafficking across the Sahel, which involves goods ranging from cigarettes and stolen cars to drugs, weapons, and persons. This has evolved into a broad and interconnected “economy of insecurity.” At stake are the business interests, alliances, and rivalries of state officials, tribes, or factions of tribes. Many tribes have historically occupied vast areas that straddle international boundaries, such as the Rgueybat, who inhabit parts of Mauritania, Morocco, and the Western Sahara. Some groups, such as the Ideybussat and the Tajakant, have been so successful that they have expanded beyond the region to the Persian Gulf, where they do business in the region’s commercial hubs, such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi.3

Competition and influence over this transborder trade is decades old, and to some degree explain how tribes and clans have engaged in various conflicts. In northern Mali, smuggling “remains a long-cherished symbol of autonomy and control and an important part of both social practices and shifting political alliances.”4 Further complicating matters, such transborder traffic is shaped not only by intergroup politics but also by specific individuals. Because of tribal structures and traditions, individual personalities sometimes “make” the tribe more than the reverse.5 Swings in influence and authority, then, are sometimes reduced to the strength of individuals with distinct and complex interests.

Local politics can also seriously blur the differences between state and nonstate actors. It is no secret that some state officials from Mauritanian border regions (in the military, in the customs administration, and elsewhere) have used their position and resources to further their private or clan’s business interests. Similarly, “many agents of the state on the Malian and Algerian sides of the border consider their position in the state apparatus as a means to feed their tribal solidarity with state money.”6 In the zones inhabited by Malian Tuaregs, “customs officials and the smugglers often belong to the same clan.”7

“Allegiances to one’s ethnic group, tribe, clan, or personal network can be stronger than those to the state.”

The argument that the state cannot control these illegal economic transactions, therefore, misidentifies the problem. In fact, some high-ranking military officers, as well as members of their families and tribes, play key roles in this illicit economy and are involved in numerous local power struggles. The result is a seemingly irreconcilable tension: the state as an abstract entity is threatened by this illicit business, yet simultaneously many state agents are deeply involved in these activities. The suggestion, then, that the Mauritanian state needs more technology, surveillance materials, vehicles, and capacity-building is true, but it misses the point. That state officials may follow private, social, and political incentives not congruent with the interests of the state indicates that the problem is less technical than political. Allegiances to one’s ethnic group, tribe, clan, or personal network can be stronger than those to the state.

Another common but problematic perspective is the Sahel as a no-man’s-land. Though the desert is vast, the actual areas used by humans are much more limited. All human activity—whether it is tourism, nomadism, trafficking, or terrorism—relies on the region’s key land routes and converges at water points and fuel stops. That local communities, armed Islamists, smugglers, and other groups involved in illegal activities sometimes interact at these nodes, then, is no surprise.

Similarly, many AQIM leaders are Algerian and would find it difficult to navigate the complex terrain of the Sahel without support from some local communities. Accordingly, AQIM leadership’s strategy of marrying into these communities is pragmatic. Local community support is itself a combination of grievances with the national government (“the enemy of my enemy is my friend”), practical business interests, and ideological motivations. At the least, communities notice the presence of these groups. In addition, some state officials originate from these peripheral communities, while others are stationed nearby and have relationships within them. Yet, again it is the micropolitics that supersede the interests of the state.

Islamism and Local Power Struggles

Local groups interpret, interact with, reject, or adopt Islamism and the ideology of Islamist movements in unique ways. Accordingly, although the entire population in Mauritania and most of the Sahel is Muslim, this religious identity is filtered and informed by other identities.

Castes

Most ethnic groups of the Sahel are internally organized by hierarchies of castes that define social status. These are not rigid but change over time and are geographically idiosyncratic. However, they still affect how people live their lives, and therefore how they interact with Islamism. For instance, many Mauritanian leaders in AQIM come from Moorish society’s top-tiered “free” Zwaya tribes of the southwest region. The Zwaya have historically specialized in religious scholarship, providing most of the region’s religious scholars (ulama, qadi, Imam, and others) who oversee traditional religious schools (called mahadra in Mauritania). By contrast, the vast majority of Haratin, lower tiered “freed captives” of Moorish society, are extremely poor and can hardly move up the socioeconomic ladder. Given that context, many Haratin have been attracted by the egalitarian discourse (“all equal before God”) of Islamist movements such as Tabligh wa Da’awa. Founded in India in the 1920s, this orthodox but nonviolent group has become the largest transnational Islamist order in the world. It seeks a re-Islamization of Muslim societies from below and therefore rejects the caste hierarchy and any other form of ethnic or racial distinctions. While attracting far fewer followers, violent groups such as AQIM also use an egalitarian antiestablishment discourse that rejects ethnic, national, or racial differences. This could explain why Mauritania’s only two homegrown suicide bombers were Haratin.

Ethnicity

Islamism in Mauritania cannot be understood without an appreciation of its history of ethnic power struggles. For example, counterintuitively, few members of Mauritanian Islamist groups come from the Haalpulaar, Sooninko, and Wolof ethnic minorities of the Senegal River Valley, though they are all Muslim, have often been targeted by state security forces, and comprise roughly 30 percent of the population. This is largely because power struggles fought in the name of ethnoracial identities have historically marginalized Black Africans. Islamist movements are often unable to bridge such differences, preventing them from reaching individuals outside the Moorish community. In fact, in the villages of the Senegal River Valley and neighborhoods of Nouakchott where Black African ethnic minorities have settled, many conceive of Islamism as a reincarnation of an older “Arab nationalist” ideology that favors the “Arabness” of Mauritania to the detriment of its non-Arab communities.

“Violent groups such as AQIM use an egalitarian antiestablishment discourse.”

In Mali and Niger, where the governments are predominantly controlled by ethnic “Southerners” (or Africans), the economic and political marginalization of Tuareg communities during most of the postcolonial period also factors into the pull of Islamism. Having been deprived of development resources and access to ruling political coalitions for decades, some northern Tuareg communities are similarly suspicious of their governments’ calls to fight the “Islamist enemy.”

Meanwhile, in Algeria and Morocco, the unresolved issue of the “Sahrawi problem” in Western Sahara creates broader challenges. Prospects for youth stuck for years in Sahrawi refugee camps are gloomy. Understandably, some may be tempted by more adventurous business-related or ideological alternatives.

Clans

Interclan rivalries also matter. For instance, the arrival of the Tabligh wa Da’awa movement in Mali’s northern region of Kidal at the end of the 1990s added a new layer to longstanding clan interactions. As one clan adopted new Tabligh doctrine, others would immediately reject it, mostly because of historical rivalries.8

In short, the transborder illicit economy, Islamism, and other phenomena are all constantly shifting and are frequently reappropriated or rejected by local actors who interpret and perceive these external influences through local lenses.

Incumbents Wave the Flag of National “Security”

Local and national power struggles also often intersect. The Mauritanian regime, like its counterparts in Chad, North Africa, and to some extent Niger, struggles with a legitimacy deficit. As authoritarian systems, they all face domestic discontent and resort to a mixture of repression and co-optation to check internal opponents. In such contexts, “insecurity” is used by incumbents, or at least rival factions within these regimes, to command greater authority.

Deciphering the sources of insecurity in regimes where the military is a dominant political actor requires paying close attention to the dynamics of factionalism within the security forces.9 For instance, Mauritanians remember the clashes between two of former President Ould Taya’s cousins between 2003 and 2005 as well as the more recent tensions between current President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz and his cousin and predecessor. More generally, the only engine of leadership change since 1978 has been the coup d’état. In each instance, military officers have ousted military officers. The sole exception was President Ould Shaykh Abdellahi’s election in 2007, though he was subsequently deposed and replaced after 17 months by his military chief of staff, General Ould Abdel Aziz, confirming the rule. Indeed, every recent coup d’état has been fomented by close collaborators of the ousted leader. Given this unpredictable environment, the recent arrests of high-ranking Mauritanian officers for drug trafficking does not necessarily mean that the government is cracking down on this trade. Rather, identifying which officials have not been arrested and who is responsible for the arrests is often a more revealing piece of information.

Insecurity in the Sahel may also be conceived as a political resource for incumbent regimes. During President Taya’s rule in Mauritania from 1984 to 2005, the regime instrumentalized notions of insecurity to impose a wide range of restrictions, often in the name of counterterrorism.10 During the last 5 years of Taya’s reign, Mauritanian security forces arrested dozens of people labeled as “Islamists,” ranging from youngsters suspected of belonging to Islamist militias to mainstream Imams and opposition politicians such as the current head of the Islamist Tawassoul party, which has never called for violence but advocates for financial disclosures of politicians and security officials. In addition to silencing influential local actors, the regime successfully capitalized internationally on the climate of fear to attract external support. Western countries, mainly the United States and France, and to some extent the European Union, provided the Taya regime with financial, material, and diplomatic backing. In similar ways, the Nigerien and to some extent Malian governments have used the theme of “insecurity” to clamp down on Tuareg and other communities. This strategy has often backfired, simply intensifying animosity towards the government.

Much can be learned from these experiences. The 2008 coup was widely condemned internationally precisely because it abruptly interrupted a democratic transition many had applauded. However, “insecurity” and “instability” were soon mobilized to justify support for the new military strongman in Nouakchott, General Ould Abdel Aziz. Several analysts have raised the possibility that leading up to the coup “a number of [violent] acts were ordered to destabilize the presidency of Ould Abdellahi and undermine his credibility in the eyes of his foreign partners, especially France.”11 Shortly after the coup, General Ould Abdel Aziz publicly claimed that the previous president was too soft on Islamists and that only he could provide security. France quickly extended its support. The United States, though the leading nation among those that strongly condemned the coup, eventually resumed its support after the general organized and won presidential elections in 2009. In short, when governments in the Sahel wave the flag of “instability,” it may be concealing more complex domestic dynamics.

Regional Rivalries Overwhelm Mutual Interests

The ongoing dispute in the Western Sahara, the Tuareg rebellions in Mali and Niger (and indirectly in Mauritania), and the Algerian civil war of the 1990s–2000s all continue to influence insecurity at both the regional and national levels. These conflicts have created a “political economy of conflict” featuring trade in arms and illicit goods, which sponsors the activities of communities and political actors across the Mauritanian borderland and the Sahel more generally. Consequently, local politics adapt to and intertwine with these regional dynamics. Commercial routes, for instance, are sometimes reconfigured according to the needs of Tuareg and Sahrawi groups and how they relate with their enemies of the moment, whether they are regional governments or rivals within their own communities. As a result, rebel groups originally organized around some political grievance eventually involve themselves in trafficking activities unrelated to their primary aims, as illustrated by kidnappings of foreigners by AQIM for financial gain.

Political rivalries among regional neighbors also complicate the drivers of insecurity. In most African conflicts, armed groups are enabled by neighboring governments or factions within governments who provide financial and military support or simply tolerate their presence. Since the conflict in Western Sahara in the 1970s, the ambiguous status of the Sahrawi communities as well as former and active Polisario combatants has been a constant source of contention between Algiers and Rabat, periodically transforming Mauritania into a proxy battlefield. Similarly, every time there is a coup d’état in Mauritania, rumors spread about Morocco’s or Algeria’s role.

Such regional rivalries permeate analysis of seemingly unconnected political developments, thereby frustrating cooperation and feeding suspicion. Interpretations of the December 2010 arrests in Mauritania of alleged Polisario activists who may have had business relations with AQIM are a case in point. Some concluded that the Algerians had either turned a blind eye on their Polisario “protégés,” or, worse, were using them to help AQIM, a group whose very existence buttresses Algeria’s image as regional counterterrorist champion. To others, the allegation of Polisario-AQIM connections was simply a manipulation by the Moroccan government to tarnish the reputations of its opponents, the Polisario and Algeria. Again, regional rivalries make it hard to interpret and understand what is really happening, let alone act on this information.

Some Lessons

Three broad lessons emerge from the layered complexity of insecurity in Mauritania and the Sahel more generally.

Avoid dichotomous thinking and shortcuts to knowledge.

The frequently presented choice of either stability provided by the military (sometimes in civilian clothes) or the violence of Islamist terrorists is artificial. So is the binary notion of the state versus insurgents and traffickers (that is, non-state actors). Policymakers and analysts must devote more time and resources to consider the complexity of the region. Among the issues worth studying at length are the spectrum of rivalries among tribes specializing in illicit commerce, the tensions between castes, the impact of ethnicity on Islamist mobilizations, the personal competition between military officers, the political economy of Sahelian communities such as the Tuareg, and the complex and at times contradictory structures of loyalty, including those to the state (an employer), a tribe, and personal interest. Devoting more time to acquiring and maintaining a deep knowledge of the region will improve international policy engagement, better respond to the real needs of the region, and lower the risk of analysts being manipulated by local actors who know how to “talk” to them.

Build stronger loyalties through genuine development and political outreach to marginalized communities.

“The choice of either stability provided by the military (sometimes in civilian clothes) or the violence of Islamist terrorists is artificial.”

Some communities in the Sahel have been denied access to decisionmaking circles and development schemes for decades. Exclusion from state institutions and political processes has eliminated channels through which their legitimate interests can be assessed and incorporated in transparent and nonviolent ways. This exacerbates already opaque insecurity dynamics throughout the region. Sustainable development programs, as well as inclusive political solutions, are particularly relevant. For instance, the official recognition of Mauritania’s moderate Tawassoul Islamist party by the government in 2007 was constructive. The exclusion of this moderate player for some 17 years nurtured antigovernment discourses. From a socioeconomic point of view, Malian initiatives such as the Investment and Development Fund for the Socioeconomic Rehabilitation of the Regions of Northern Mali are a good start. So is Mauritania’s Program for the Prevention of Conflicts and the Consolidation of Social Cohesion, which is directed at both Haratin and returning Black African refugees. The resources channeled into these programs, however, are unquestionably insufficient. Given that Sahelian countries are among the poorest in the world, their international partners can play a significant role in providing support to assist these countries’ development programs among marginalized communities.

Meanwhile, outreach should not be equated with the militarization of these areas. If these local communities begin to witness the rising presence of their national governments’ security forces—or that of their international partners—this outreach would backfire.

Support legitimate political regimes.

International partners should provide strong support to democratic regimes and those that are implementing democratic changes, while pressuring those that opt for authoritarian policies. The unfolding Arab Spring is demonstrating what some Sahelian and sub-Saharan countries already knew: legitimate governments are less subject (though not immune) to the opposition of armed groups and better equipped to respond to societal demands. Mali, for example, is much less subject to antigovernment violence than regimes that employ an authoritarian style. The greater legitimacy of democracy mutes the resonance of calls for jihad and armed rebellion, except in specific regions, not coincidentally, where these regimes underperform, as in northern Mali. Autocratic Mauritania and Algeria, on the other hand, have been directly targeted, both in words and deeds. International partners of Sahelian countries, as well as regional organizations such as the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States, should strongly and consistently condemn authoritarian actors such as military coup–makers or unconstitutional heads of states (for example, Niger’s former President Tandja) that threaten the development of democratic institutions and practices.

Dr. Cédric Jourde is an Associate Professor at the School of Political Studies, University of Ottawa, Canada. His research focuses on the politics of identities in Sahelian countries and on dynamics of regime change and regime survival.

Notes

- ⇑ Shinqit is the ancient name used in the Arab world to refer to most of what is today Mauritania. Murabitun is the name of a local group that eventually invaded Morocco and Spain at the turn of the 11th century.

- ⇑ On Western “representations” of Mauritanian politics, see Cédric Jourde, “Constructing Representations of the ‘Global War on Terror’ in the Islamic Republic of Mauritania,” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 25, no. 1 (2007), 77–100.

- ⇑ Armelle Choplin, “From the Chinguetti Mosque to Dubai Towers,” The Maghreb Review 35, nos. 1–2 (2010), 146–163.

- ⇑ David Gutelius, “Islam in Northern Mali and the War on Terror,” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 25, no. 1 (2007), 70.

- ⇑ Zekeria Ould Ahmed Salem, “Prêcher dans le désert: l’univers du Cheikh Sidi Yahya et l’évolution de l’islamisme mauritanien,” Islam et sociétés au sud du Sahara 14–15, (2001), 6.

- ⇑ Judith Scheele, “Tribus, États et fraudes: la région frontalière algéro-malienne,” Études rurales, no. 184 (July–December 2009), 91. Emphasis added.

- ⇑ Baz Lecocq and Paul Schrijver, “The War on Terror in a Haze of Dust: Potholes and Pitfalls on the Saharan Front,” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 25, no. 1 (2007), 159.

- ⇑ Ibid., 149–150.

- ⇑ Abdel Wedoud Ould Cheikh, “Une armée de tribus? Les militaires et le pouvoir en Mauritanie,” The Maghreb Review 35, no. 3 (2010), 339–362.

- ⇑ Cédric Jourde, “The International Relations of Small Neoauthoritarian States: Islamism, Warlordism, and the Framing of Stability,” International Studies Quarterly 51, no. 2 (June 2007), 481–503.

- ⇑ A. Antil and C. Lessourd, “Non, mon Président! Oui, mon général! Retour sur l’expérience et la chute du président Sidi Ould Cheikh Abdallahi,” L’Année du Maghreb 2009, V (2009), 382.