Ras El Bar, Egypt jutting into the Mediterranean Sea. (Image: Google Earth)

African coastlines have experienced a steady rise in sea levels for four decades. At the current pace, sea levels are projected to rise by 0.3 meters by 2030, affecting 117 million Africans. If global warming is contained to 2˚C above 1990 levels, sea level rise may be limited to 0.4 meters. However, a 4˚ C level of global warming would lead to a 1-meter rise in sea levels by the end of the century.

The global rise in sea levels is an outcome of the buildup of greenhouse gas emissions that has resulted in a 0.63˚C-increase in median ocean temperatures over the past century. Rising ocean and atmospheric temperatures have resulted in the melting of the polar ice caps and thermal expansion (which causes the volume of water to increase), causing the increase in ocean levels.

Rising sea levels are triggering coastal flooding and erosion as well as the loss of the coastal habitats that provide natural shoreline protection from storm surges. The loss of these habitats increases the number of people at risk.

The rise in sea levels is occurring as the population of Africa’s coastal cities is skyrocketing.

The rise in sea levels is occurring as the population of Africa’s coastal cities is skyrocketing. Between 2020 and 2030, Africa’s 7 largest coastal cities—Lagos, Luanda, Dar es Salaam, Alexandria, Abidjan, Cape Town, and Casablanca—are projected to grow by 40 percent (48 million people to 69 million) compared with the continent’s overall anticipated increase of 27 percent (1.34 billion to 1.69 billion). Smaller coastal cities may expand even faster: Port Harcourt in Nigeria, for example, is expected to grow 53 percent over this decade. Globally, Africa’s coastal regions are anticipated to experience the highest rates of population growth and urbanization in the world.

This demographic pressure is being driven by the economic significance of Africa’s coastal cities. Africa’s blue economy—comprising ports, fisheries, tourism, and other coastal economic activity—is conservatively projected to grow from $296 billion in 2018 to $405 billion by 2030. Coastal megacities like Lagos and Dar es Salaam power national economies. The GDP of Lagos, for example, is greater than 46 of Africa’s 54 countries.

Africa’s coastal cities serve as the critical gateways to the continent’s vast interior. Disruptions to port cities caused by rising sea levels can have cascading effects on the logistical networks and economies that they support. An estimated 90 percent of Africa’s import and export trade comes through coastal ports.

With a rapidly growing share of Africans living in coastal regions, rising sea levels represent a highly tangible and disruptive impact of global warming on a continent already experiencing rapid population growth and land pressures. In addition to population displacements, rising sea levels will place enormous strain on infrastructure, agriculture, and water access for African citizens, heightening the risk of instability.

Threats to Infrastructure and Public Health

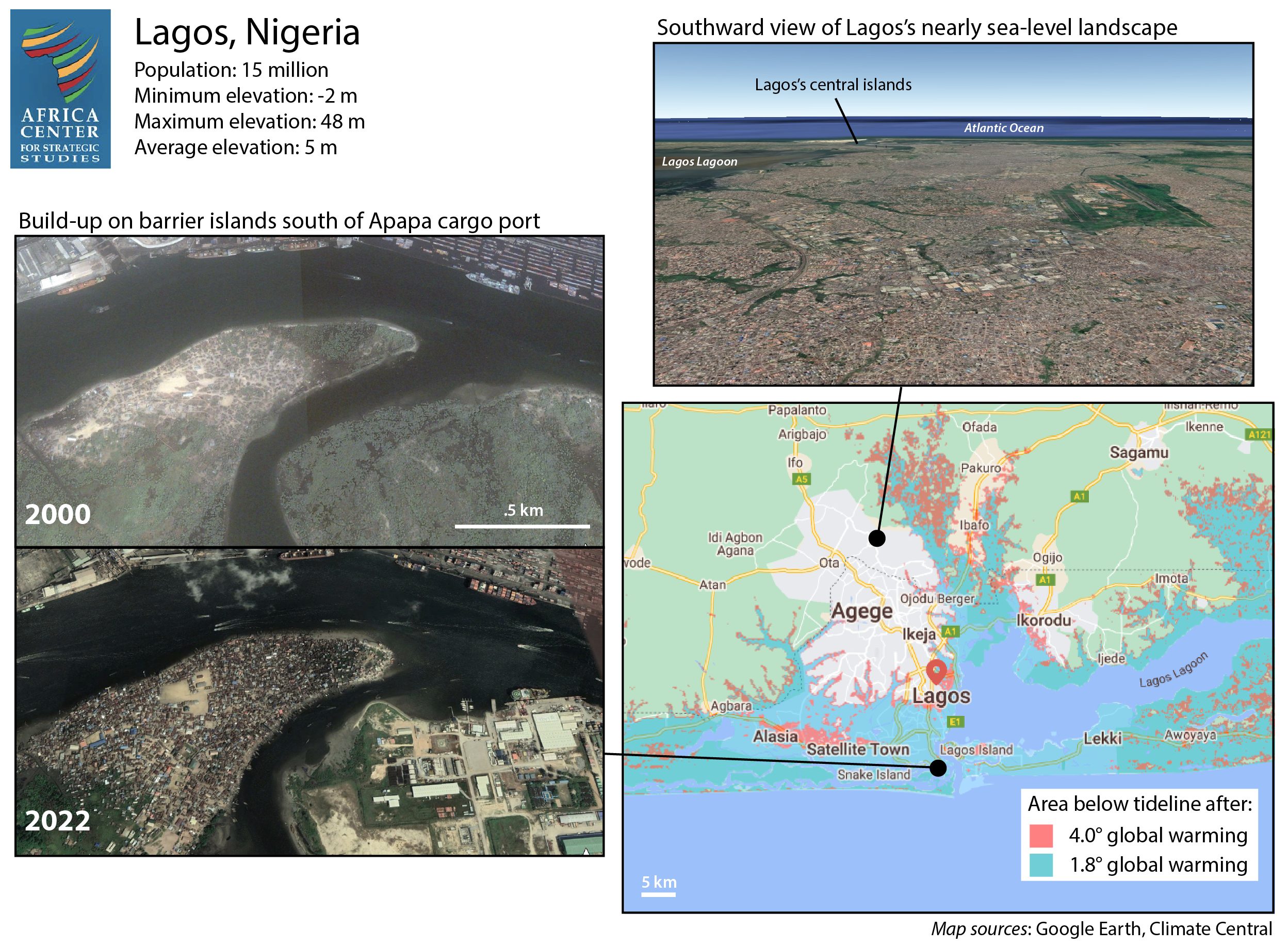

Coastal cities not only face the direct threat from rising sea water and storm surges. They also face the unseen threat from groundwater rising, turning urban areas into wetlands. From the erosion of roads and building foundations to backflowing sewers, leeching septic systems, inundated cesspools turned microbe breeding ponds, cities will face myriad infrastructure and public health crises. In Lagos, 50 percent of hospitalized patients suffer from water-borne diseases.

Rising sea levels also threaten coastal residents by contaminating aquifers. Coastal aquifers provide water for drinking and irrigating crops. Coastal aquifers are vulnerable to saltwater intrusion, even from minor rises in sea levels, particularly in the coastal areas of North Africa where groundwater is overexploited to support the growing population and agriculture.

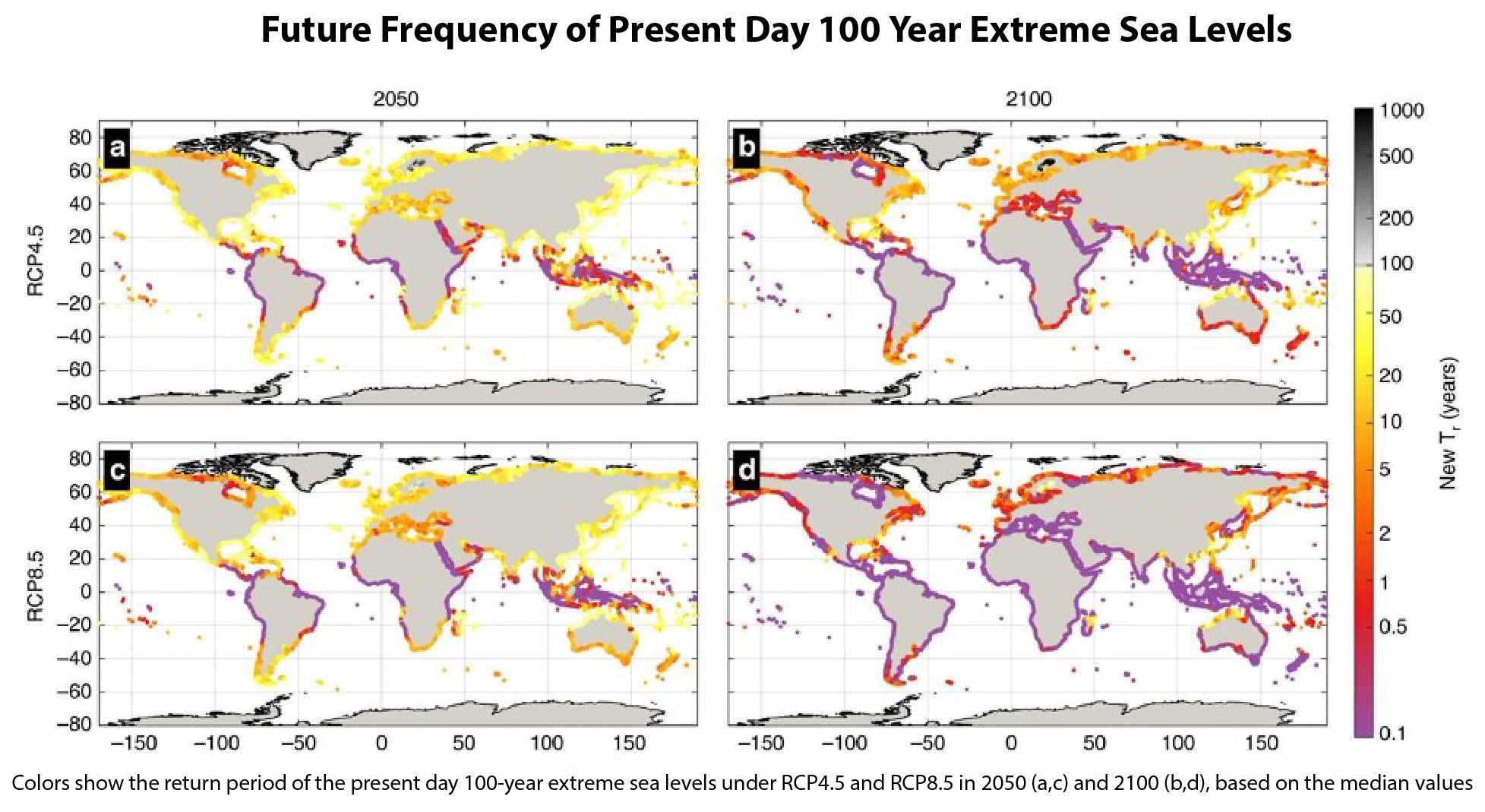

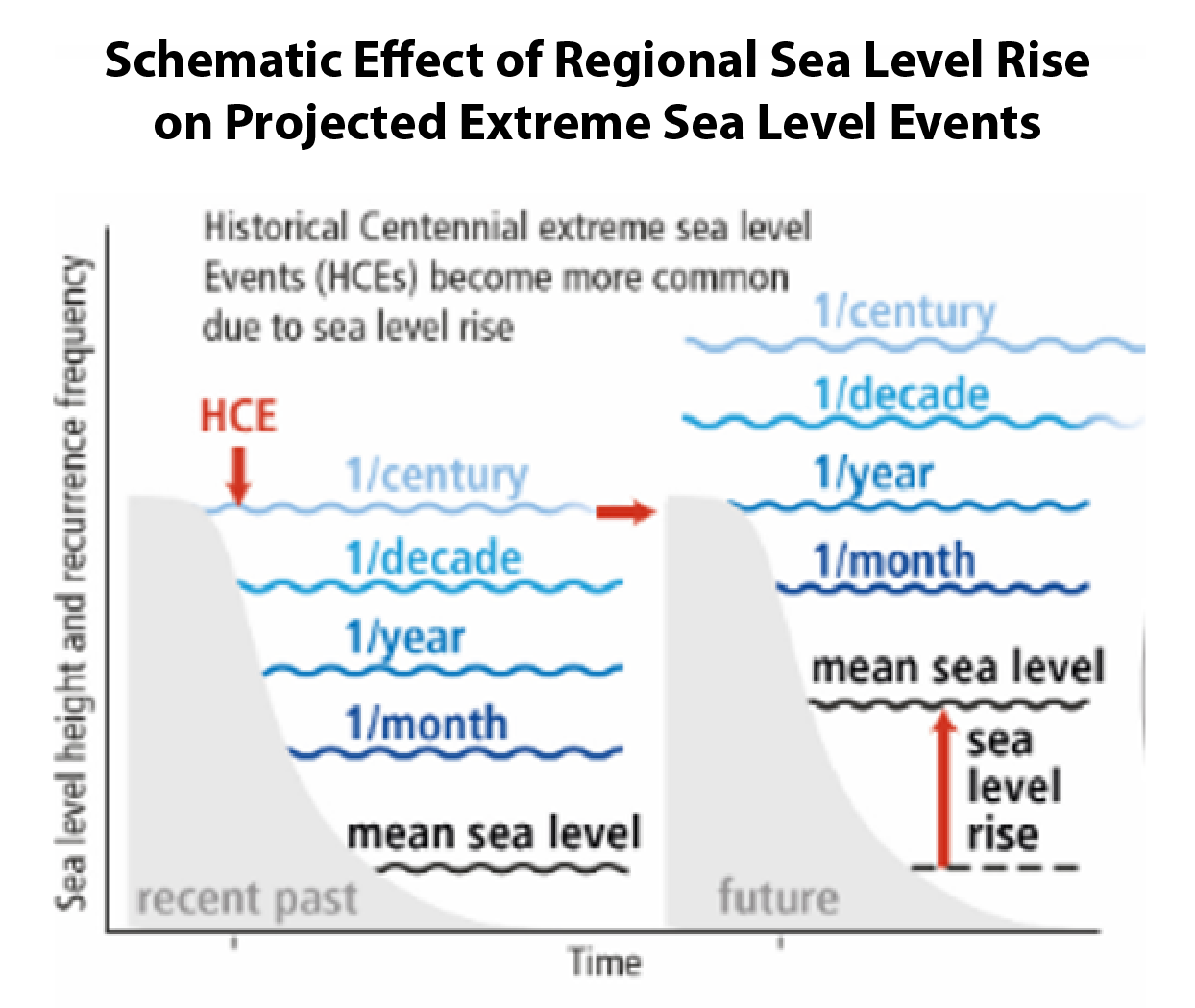

Rising oceans are also behind the increasing incidences of “100-year floods” (having a one percent chance of occurring in any given year). Historically rare, extreme sea level events (the combination of mean sea level, tides, and wave surges) are occurring increasingly frequently, especially in tropical regions. Across large African river basins, the frequency of 100-year flood events is projected to increase to 1 in 40 years at 1.5°C and 2°C global warming, and 1 in 21 years at 4°C warming. Under the business-as-usual model, for some parts of coastal West and East Africa, these extreme outcomes could become annual events.

Source: Nature Communications

Source: IPCC

Warming Oceans

Since the 1980s, marine heatwaves have become more frequent, more intense, and longer, exposing species and ecosystems to environmental conditions beyond their tolerance limits.

The number of African marine heatwaves doubled in the North African Mediterranean Sea and along the Somalian and southern African coastlines from 1982–2016. If global warming continues unabated, the strength and duration of these events are expected to overwhelm the ability of many marine organisms to adapt. This will result in the destruction of marine ecosystems and the extinction of numerous marine species. Impacts include repeated mass coral bleaching events in East Africa and the poleward migration of marine life from their original habitats, leading to lost livelihoods for African fishers. This would result in a 30-percent contraction of Africa’s $25 billion annual marine fisheries sector by 2050 with West Africa being particularly hard hit.

Rapidly Expanding Populations in Low Elevation Coastal Zones

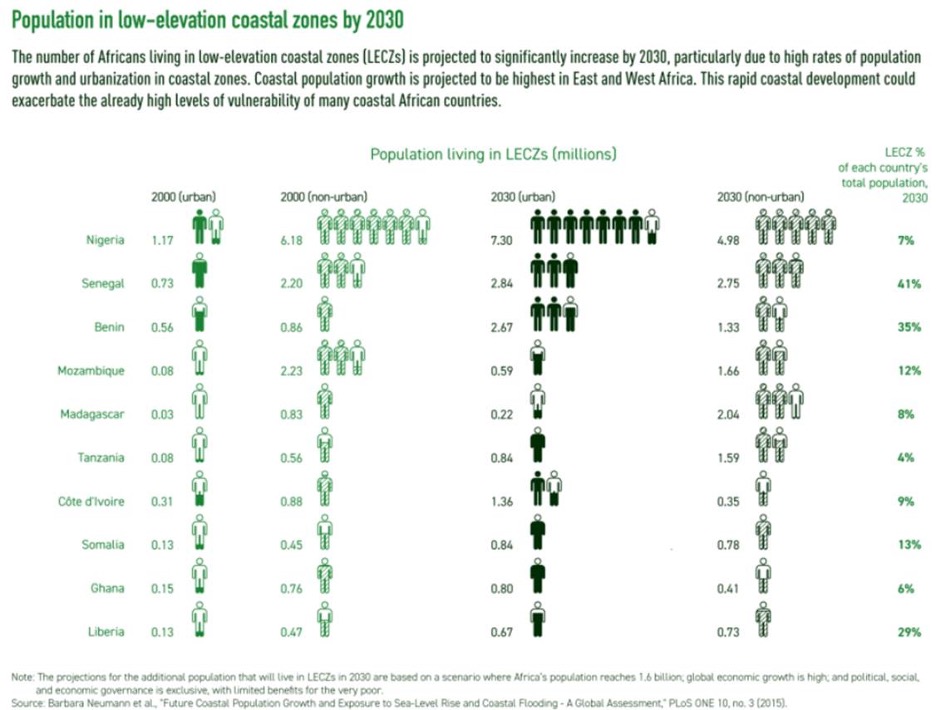

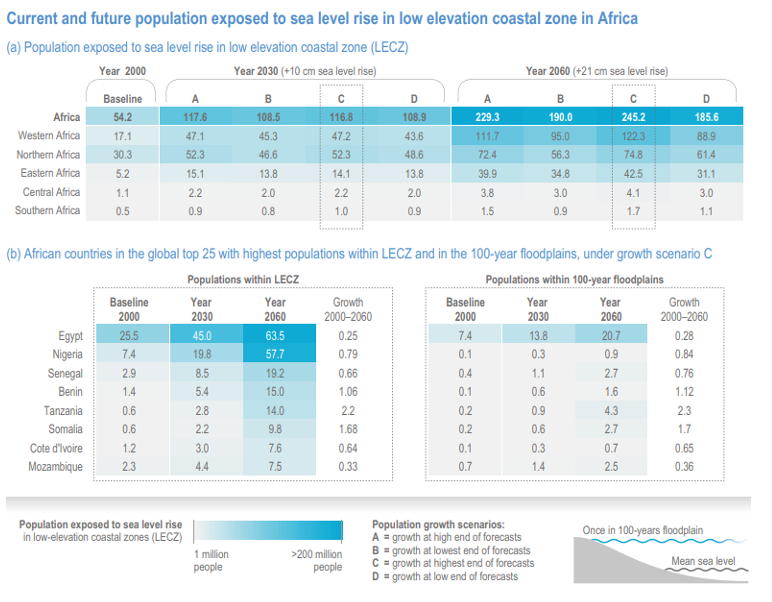

By 2030, an estimated 108–116 million people in Africa will live in low elevation coastal zones—defined as areas 10 meters or less above sea level, a figure projected to double by 2060.

In the near term, North and West Africa will be most directly affected, comprising 85 percent of the projected 100 million population affected on the continent, though every region is threatened. Egypt and Nigeria, both with high density metropolises near the coast, are anticipated to face the greatest population disruptions. In Egypt, a 0.5- to 1-meter sea level rise will result in the coastline shifting inland by several kilometers, submerging a large area of the Nile Delta.

Source: Brookings

Source: IPCC

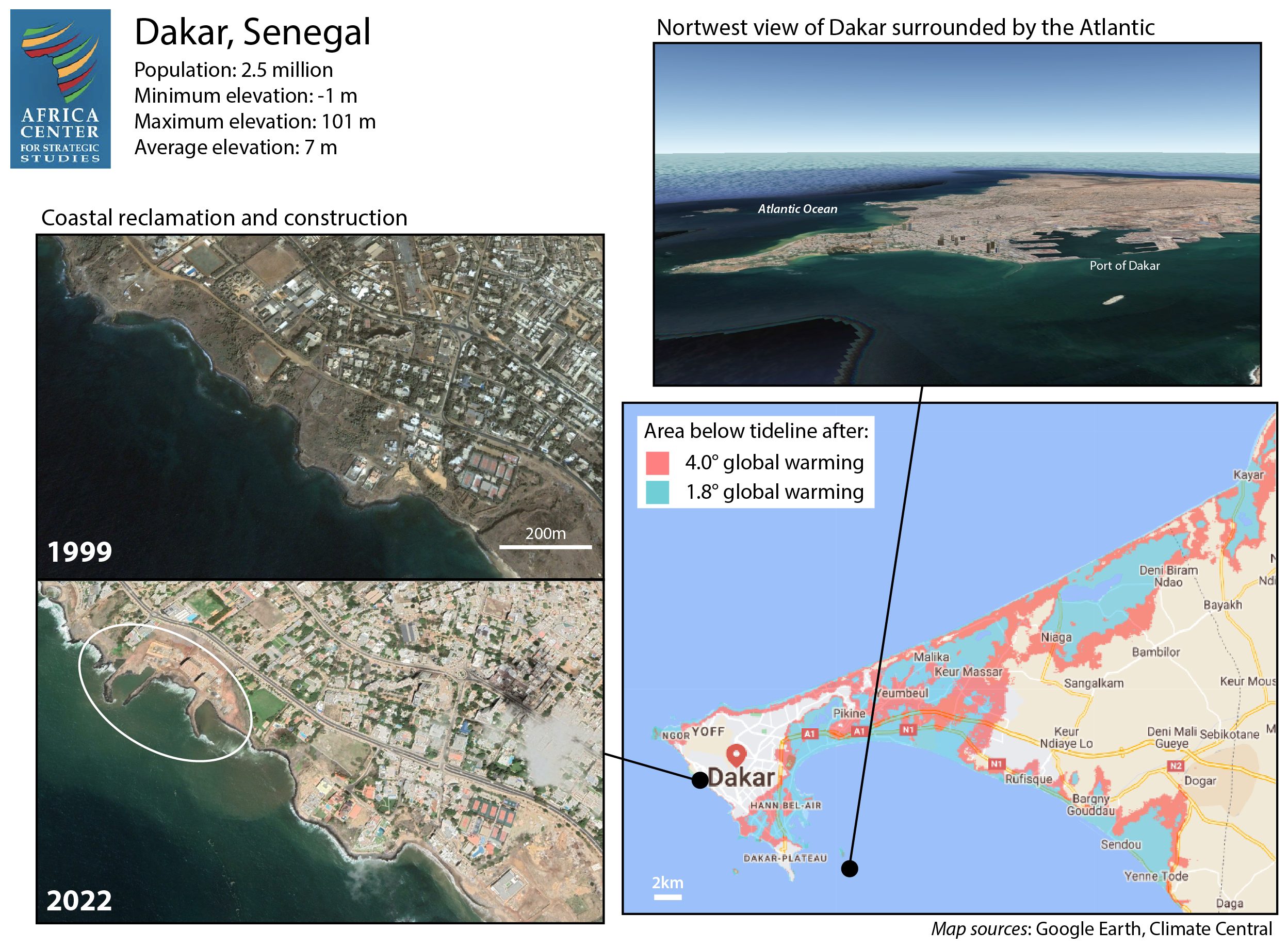

Africa’s vulnerability is exacerbated by rapidly increased coastal development. Unfortunately, some of the more densely packed cities—such as Lagos, Dakar, and Alexandria—are victims of poor coastal planning. They are not alone. About 56 percent of the coastline in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, and Togo is exposed to an average erosion of two meters per year. The World Bank estimates this erosion, flooding, and pollution inflict $3.8 billion in damage for these countries annually. Many coastal residents will be forced to relocate.

Countries where large proportions of the population live on the coast—such as Senegal (41 percent), Benin (35 percent), and Liberia (29 percent)—are particularly impacted by sea level rise.

Without adaptation, damages from sea level rise and extreme sea level events to 12 major African coastal cities, under medium and high emissions scenarios, are projected to be between $65 billion and $86.5 billion by 2050. If low-probability, high-damage events are factored in, those costs double.

Cities Most at Risk

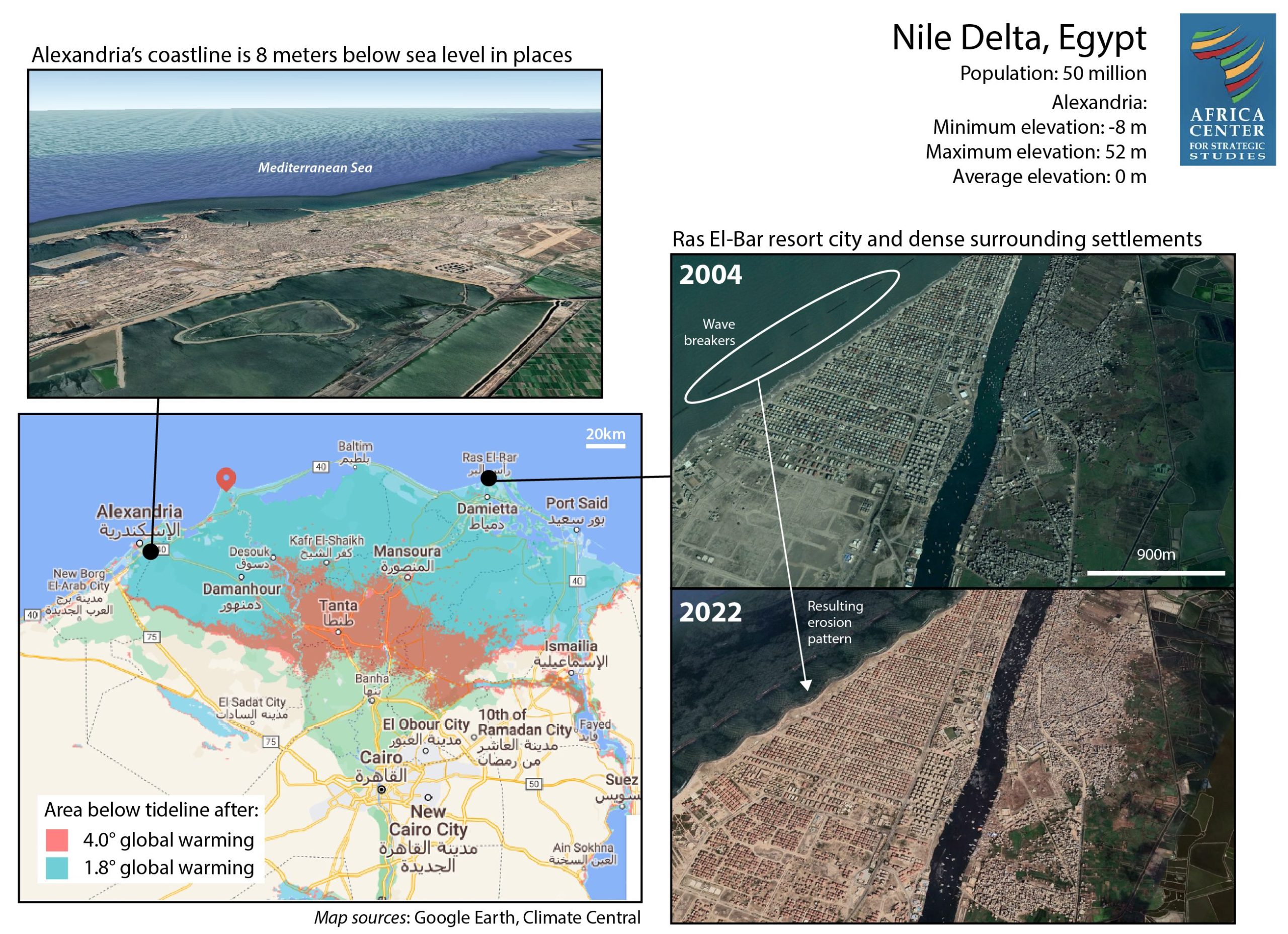

Alexandria is just one of several low-lying, densely packed coastal cities in the Nile Delta at serious risk of becoming submerged in the next three decades. The Nile Delta (excluding Cairo) is home to 50 million people or 57 percent of Egypt’s population. The lifeblood of the country, the region contains more than 60 percent of Egypt’s agricultural lands and fisheries production.

Alexandria is just one of several low-lying, densely packed coastal cities in the Nile Delta at serious risk of becoming submerged in the next three decades. The Nile Delta (excluding Cairo) is home to 50 million people or 57 percent of Egypt’s population. The lifeblood of the country, the region contains more than 60 percent of Egypt’s agricultural lands and fisheries production.

A vulnerability assessment of the cities of Alexandria, Rasheed (Rosetta), and Port Said found that the likely sea-level rise of 0.5 m could see more than 2 million people abandoning their homes, 214,000 jobs lost, and over $35 billion lost in property value and tourism income by 2050. Not included was the loss of the globally renowned historic, cultural, and archaeological sites, nor the food insecurity threatened by the loss of agricultural land.

If sea levels rise to 1 m, Alexandria alone is expected to experience $50 billion in damages. In addition, some 6 million coastal inhabitants from the Delta will likely relocate inland to Greater Cairo, an already heavily populated metropolis of about 21 million, that also happens to be vulnerable to flooding. Without proper planning, such massive relocation could lead to a cascade of crises befalling one of Africa’s largest cities.

Home to more than 15 million people and expected to be the world’s largest city by the end of the century, Lagos, a low-lying city on Nigeria’s Atlantic coast, also experiences the triple impact of perennial fluvial (river), pluvial (rainfall), and coastal flooding. Adding up the damages to assets, economic production, and mortality, the World Bank found the total cost of just fluvial and pluvial flooding in Lagos is $4 billion annually. Rising sea levels combined with high urbanization will exacerbate future damage. By some estimates, at the 3°C global warming scenario, a third of Lagos’s population will be displaced by the sea.

According to the World Bank, $39 billion worth of economic assets are vulnerable to flooding in the Dakar region. Further north, St. Louis, Senegal, founded in 1659 is disappearing under the rising sea. Many residents have been displaced. The city is a particularly acute example of problems common across several coastal metropolises in West Africa, from Ivory Coast’s economic hub Abidjan to Guinea’s capital Conakry. Major economic assets including Abidjan’s port, which is the largest in Côte d’Ivoire, and much of the international airport are on land less than 1 m above sea level.

According to the World Bank, $39 billion worth of economic assets are vulnerable to flooding in the Dakar region. Further north, St. Louis, Senegal, founded in 1659 is disappearing under the rising sea. Many residents have been displaced. The city is a particularly acute example of problems common across several coastal metropolises in West Africa, from Ivory Coast’s economic hub Abidjan to Guinea’s capital Conakry. Major economic assets including Abidjan’s port, which is the largest in Côte d’Ivoire, and much of the international airport are on land less than 1 m above sea level.

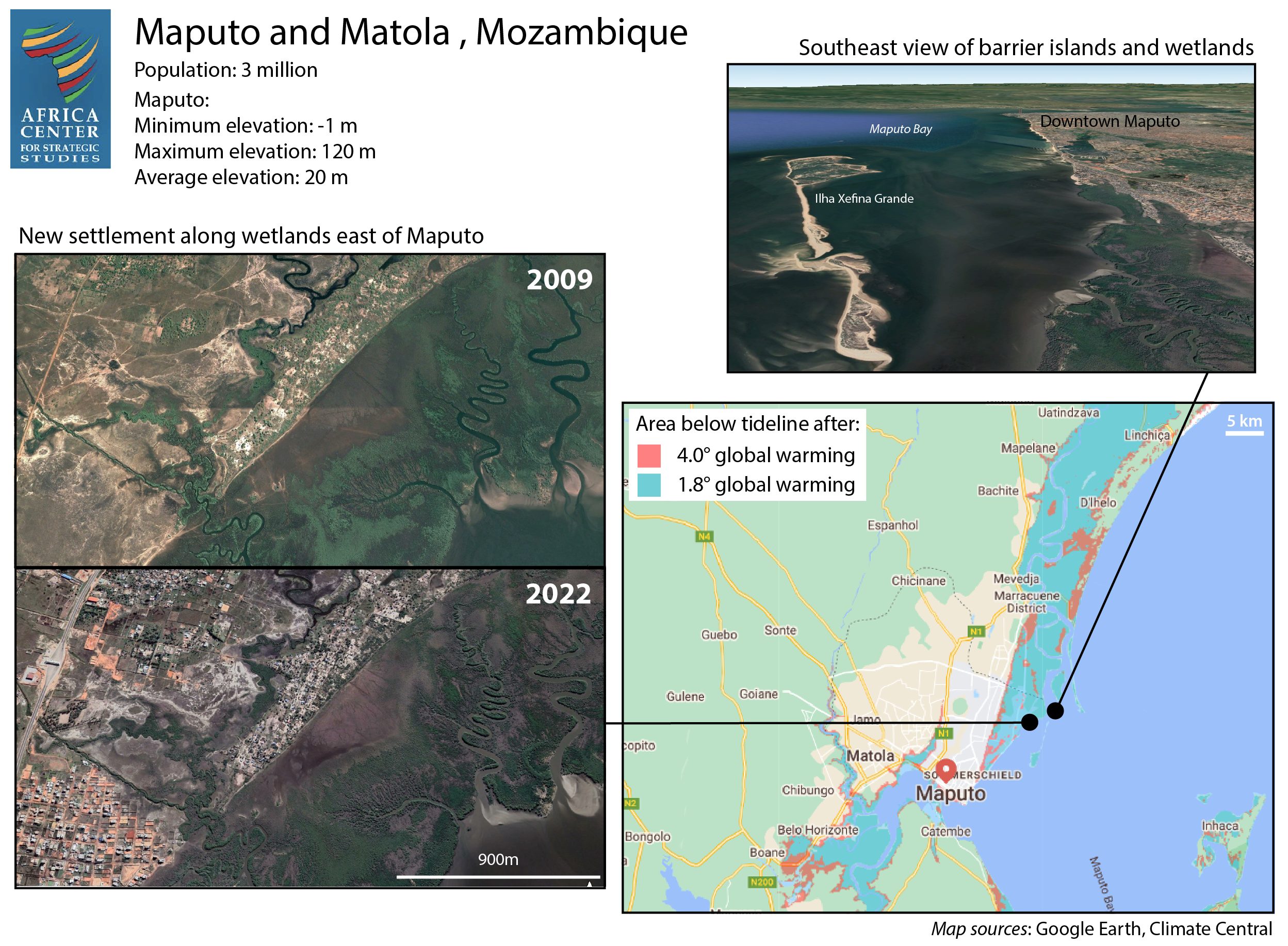

From the central Mozambican city of Beira, which was hit by the costliest African cyclone on record in 2019, to the connected cities of Maputo and Matola in southern Mozambique, some 3 million people are increasingly exposed to rising sea levels. Mozambique’s coastal cities, moreover, are situated in a widening and intensifying cyclone path due to warmer sea surface temperatures.

From the central Mozambican city of Beira, which was hit by the costliest African cyclone on record in 2019, to the connected cities of Maputo and Matola in southern Mozambique, some 3 million people are increasingly exposed to rising sea levels. Mozambique’s coastal cities, moreover, are situated in a widening and intensifying cyclone path due to warmer sea surface temperatures.

Priorities for Mitigation

Africa’s coastal cities are facing converging crises—rising seas, rapidly growing populations, land pressure, and an affordable housing shortage. These crises are compounding one another as people are pushed to settle farther into the wetlands and shorelines surrounding cities, exposing these settlements to storm surges and flooding while weakening the protection these natural barriers and ecosystems provide the entire city. Mitigating the effects of rising seas, therefore, will require simultaneously addressing other sources of vulnerability (such as balancing between high-end developments that displace residents and affordable housing options).

Africa’s coastal cities are facing converging crises—rising seas, rapidly growing populations, land pressure, and an affordable housing shortage.

The Global Center on Adaptation has implemented rapid climate risk assessments (RCRA) in five cities, including the coastal cities of Bizerte (Tunisia), Conakry (Guinea), and Libreville (Gabon). Some of the most cost-effective measures for reducing loss and damages from extreme weather events generated from these RCRA’s include investing in water and sanitation infrastructure, restoring wetlands and ecosystems to reduce flood risks, and strengthening disaster evacuation planning. The RCRA process revealed that strong local champions within municipalities were instrumental in identifying climate risks, generating data, and developing realistic solutions.

Instead of investing in expensive and maintenance-heavy infrastructure projects to defend against storm surges, many African coastal cities might choose the nature-based solution of restoring mangroves, dunes, seagrasses, wetlands, and other costal ecosystems. Even New York City abandoned its plans for an expensive seawall to invest instead in enlarging barrier islands (“living shorelines”).

One such “green infrastructure” initiative is the Management of Mangrove Forests from Senegal to Benin, which aims to protect fragile mangrove ecosystems and sustainable riparian economies as a means to enhance resilience to climate change. Another, the West Africa Coastal Areas Management Program is a public-private partnership intended to strengthen integrated local, national, and regional coastal management strategies across 17 West African countries.

A view of where the lagoon meets the ocean in Aneho, Togo. Togo and Benin authorities participate in a joint project called WACA (West Africa Coastal Areas Resilience Investment Project) to protect the transnational coastline. (Photo: AFP/Matteo Fraschini Koffi)

In Quelimane, Mozambique, the Coastal City Adaptation Project began restoring a protective layer of mangroves in 2015. These investments, accompanied by education among local communities on the importance of mangroves, paid off when Cyclone Idai hit in 2019. According to the mayor of Quelimane, Manuel de Araújo, “Ultimately, it’s our mangroves that saved us. They are our first line of defense. The day we don’t have mangroves, I don’t think our city will survive.”

There is no single silver bullet to address sea level rise. Layered and mutually reinforcing policy responses are needed. These must be focused on fundamental questions about whom cities are for and whom they prioritize as they grow and adapt. By balancing ecological, economic, and political strategies, municipal and national leaders can strengthen the resiliency of Africa’s coastal cities as they adapt to the threat posed by rising sea levels.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Cycles of Escalating Threats Facing Africa from Global Warming,” Infographic, June 17, 2022.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Cyclones and More Frequent Storms Threaten Africa,” Infographic, May 24, 2022.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “How Global Warming Threatens Human Security in Africa,” Infographic, October 29, 2021.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Chapter 9 Africa,” United Nations, February 2022.

- Global Center on Adaptation, “State and Trends in Adaptation Report 2022: Africa,” November 2022.

- Catlyne Haddaoui and Manisha Gulati, “Financing Africa’s Urban Opportunity: The ‘Why, What and How’ of Financing Africa’s Green Cities,” Report, Coalition for Urban Transitions, September 2021.

More on: Environment and Security